The Green, Wallsend Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Throckley Leazes Tenants and Residents Group

Throckley Leazes Tenants and Residents Group Established January 1998 Chairman Jennie Stokell Vice Chairman Secretary Carol Eddy Treasurer Sheila Grey Monday 22 August 2016 David Owen, Review Officer, (Newcastle upon Tyne) Local Government Boundary Commission for England, 14th Floor, Millbank Tower, Millbank, London, SW1P 4QP. Dear Sir or Madam, Ref : City of Newcastle upon Tyne - Draft Recommendations on New Electoral Arrangements - Callerton Throckley I have been asked by our Ward Counsellors to thank you for putting Walbottle back into this electoral ward. My Group are still not happy about this new ward created by apparently adding odd bits of the outer City to Newburn, Throckley, etc, to create a “patchwork” ward with little cohesion along its length once away from the riverside settlements. Our objections are as follows 1. Consultation. My Group are disappointed that the City Council have again failed to publise this consultation about the proposed changes to the ward boundaries and the implications to the people living in the areas. We have found when raising the issue at our meetings and in private conversations, that there is more interest than we would have expected once the whole project relating to the proposed changes around Throckley and Newburn are explained. This interest is across the age ranges of residents, not simply among the elderly who have memories of the Newburn Urban District Council and its governance of the area prior to Newburn, etc. inclusion in the City of Newcastle upon Tyne. Local people are possessive of the long term history of their area and the events which make up their social and cultural heritage. -

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020 Arthur’s Hill Benwell & Scotswood Blakelaw Byker Callerton & Throckley Castle Chapel Dene & South Gosforth Denton & Westerhope Ali Avaei Lord Beecham DCL DL Oskar Avery George Allison Ian Donaldson Sandra Davison Henry Gallagher Nick Forbes C/o Members Services Simon Barnes 39 The Drive C/o Members Services 113 Allendale Road Clovelly, Walbottle Road 11 Kelso Close 868 Shields Road c/o Leaders Office Newcastle upon Tyne C/o Members Services Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Walbottle Chapel Park Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8QH Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 4AJ NE1 8QH NE6 2SY Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE6 4QP NE1 8QH 0191 274 0627 NE1 8QH 0191 285 1888 07554 431 867 0191 265 8995 NE15 8HY NE5 1TR 0191 276 0819 0191 211 5151 07765 256 319 07535 291 334 07768 868 530 Labour Labour 07702 387 259 07946 236 314 07947 655 396 Labour Liberal Democrat Labour Labour Newcastle First Independent Liberal Democrat [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Marc Donnelly Veronica Dunn Melissa Davis Joanne Kingsland Rob Higgins Nora Casey Stephen Fairlie Aidan King 17 Ladybank Karen Robinson 18 Merchants Wharf 78a Wheatfield Road 34 Valley View 11 Highwood Road C/o Members Services 24 Hawthorn Street 15 Hazelwood Road Newcastle upon Tyne 441 -

Walbottle Conservation Character

CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2 1.1 Terms of reference: conservation areas evaluation 2 1.2 Walbottle Village – purpose of designation, principles of character and boundaries, the sub-division of the conservation area 3 2. CONTEXT OF WALBOTTLE VILLAGE 6 2.1 Historical development 6 2.2 Recent changes – Present situation 7 2.3 Landscape context 9 3. CHARACTER APPRAISAL 13 3.1 Sub-area A: The Green 13 3.2 Sub-area B: Dene Terrace 25 3.3 Sub-area C: The Waggonway 28 3.4 Sub-area D: The Bungalows 30 3.5 Walbottle Hall 33 4. MANAGEMENT PLAN 34 4.1 Introduction 34 4.2 Existing designations within the Conservation Area 34 4.3 Future Management 37 4.4 Design Guide by sub-area 45 APPENDIX 1 47 Planning context of the Management Plan APPENDIX 2 49 Legislative framework of the Management Plan: Planning Procedures Acknowledgements 52 Walbottle Village Conservation Area Character Statement & Management Plan 1 1. INTRODUCTION be the basis for local plan policies and development control decisions, as well as for the preservation and enhancement 1.1 Terms of Reference of the character or appearance of an This character appraisal has been area”. prepared in response to Government advice. Value of the Appraisal The value of the appraisal is two-fold. Conservation Areas First, its publication will improve the Conservation Areas were introduced by understanding of the value of the built the Civic Amenities Act 1967, and heritage. It will provide property owners defined as being “areas of special within the conservation area, and architectural or historic interest the potential developers with clearer character or appearance of which it is guidance on planning matters and the desirable to preserve or enhance”. -

Local Resident's Submissions to the Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Council Electoral Review

Local resident’s submissions to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Pr9hvq A ) Tr) Mishka Mayers Review Assistant LGBCE 0330 500 1251 From: Karon Alderman Sent: 18 August 2016 11:37 To: reviews <[email protected]> Subject: Newcastle ward boundary changes Dear Boundary Commission I believe that the Benton Lodge Estate, where I live, is very much part of the Dene community and should stay part of Dene Ward. Please reverse the decision on the Dene adn Manor Park ward boundariues decision and choose Newcastle Council’s Option 1 for area C as this is more in line with our communities and services. Thank you, Karon Alderman 1 ‐‐ Jonathan Ashby Review Assistant LGBCE From: Sent: 19 August 2016 13:07 To: reviews <[email protected]> Subject: Draft recommendations for Newcastle City Council Good Morning, I have attached an extract from your document concerning the above issue which is a little confusing - apologies if you are already aware of this.. As I reside in North Walbottle I have always thought that we have little in common with the existing Newburn ward and fully support the creation of a new Chapel ward and North Walbottle's inclusion within it. However, on reading the document, there is an apparent contradiction (which I assume is a simple slip of the pen/keyboard) - I have highlighted the error in yellow, and which should read simply Walbottle and not North Walbottle? Thank you. -

NORTHUMBERLAND. FIS A39 FIRE BRICK MANUFACTURS

TJU\DES DIREC'lORY.] NORTHUMBERLAND. FIS a39 FIRE BRICK MANUFACTURS. GouldbyE.CorporationFishqy.N.Shields FISH HAWKER. jlensonWm.&8on,Ill'"ewgate st.Newestl Greavea W. ~o?d, Corpora.tion Fish Lowrey Mrs. Sarah, 23 Brough build. Carr Thoml\S & Son (now WaIter Scott quay, North f::lh1elds ings Byker bank, Newcastle Limited), Victoria huildings, 21 HarveyRCorporationFish quay,N.Shlds ' Grainger street west, Newcastle Kilgour & Atkins, Corporation Fish FISH MERCHANTS. DoveJn.&Co.5SLNicholas bldgs.Newcstl quay, North Shields Bradbury Geo. Union quay, Nth. Shields Errington, Reay & Co. Tyneside brick & Lawrence Edward, Corporation Fish Brigham Robt~ HOlylsland, Beal R.S.O tile works, Bardon mill, Carlisle; quay, North Shields Brown Thomas & Sons, Seahouses depot, Bot,chergate, Carlisle McKell D.CorporationFishquay,N.Shlds Chathill RS.O ' Fl)Ster Hy.&Co.Backworth, Newcastle MayallJas. 4QJac~son~t. Nth. Shields CaisleyJames (wholesale), Low lights & Foster Henry & Co. Bank chambers. PageF.J. COl'poratlOnFlshquay,N.Shlds Corporation Fishquay, North Shields. Sandhill, Newcastle Patterson M. & Son, Corporation Fish See advert Gibson Wm. Colville, Scotswood RS.O quay, No:rth Shields Can Robert, Whitley road Whitley Heddon Coal &Fire Brick Co. (Cadwal' Rawes W. CorporationFish quay,N.Shlds RS.a. & 4 Eleanor 8tre~t Culler. lader J.Bates, fitter), 24 Side,Newest1 Read J. CorporationFishquay,N.8hields coats, Whitley RS.O ' Jameson J. & Son, We~tgate rd.Newcstl Sayer & Hollo~~y, Corporation Fish, DownieColin, Newbiggin, Morpeth Jameson & Son, Corbrldge RS.O quay, North Shwlds Edminson J. C. Beadnell, Chathill R.S.O JohnsonJobn,Prudhoe,Ovingham RS.O Shaw J. CorporationFish quay,N.Shields Ewing James, Seahollses, Chathill R.S.0 &msay G. -

Local Bus Links in Newcastle Designing a Network To

Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to TYNE AND WEAR meet your needs INTEGRATED TRANSPORT AUTHORITY Public consultation 15 March - 4 June 2010 Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to meet your needs Public consultation People in Newcastle make 47 million bus journeys annually - that’s an average of more than 173 journeys a year for every resident! Nexus, Newcastle City Council and the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority (ITA) want to make sure the network of bus services in the area meets residents’ needs. To do this, Nexus has worked together with bus companies and local councils to examine how current services operate and to look at what improvements could be made to the ‘subsidised’ services in the network, which are the ones Nexus pays for. We have called this the Accessible Bus Network Design Project (see below). We want your views on the proposals we are now making to improve bus services in Newcastle, which you can find in this document. We want to hear from you whether you rely on the bus in your daily life, use buses only occasionally or even if you don’t – but might consider doing so in the future. You’ll find details of different ways to respond on the back page of this brochure. This consultation forms part of the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority’s Bus Strategy, a three year action plan to improve all aspects of the bus services in Tyne and Wear. Copies of the Bus Strategy can be downloaded from www.nexus.org.uk/busstrategy. -

Local Area and Bus

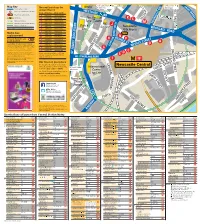

T T T T to St James’ Park T to Monument Nexus C E G Map Key Nearest bus stops for 9 minutes R RO SC 'S 8 minutes Road served by bus A onward travel R R A T WE A T M A Bus stop (destinations listed below) ST H GAT A Stop Stop no. Stop code E C ø RO N R Metro bus replacement A 08NC95 twramgmp AD O S K C T J E L O G T Metro line B 08NC94 twrgtdtw The Journal K A HN ST L F N National Rail line C 08NC93 twramgmj Tyne Theatre I M D T National Cycle Network (off-road) D Alt. GRAINGER STREET 08NC92 twramgmg S J D Dance E Hadrian’s Wall Path E 08NC91 twramgmd Gallery Newcastle U W W ARD E P Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright 2016. STG City T F 08NC90 twramgma Arts Arena ATE R G 08NC87 twramgjt OAD Metro bus REE H 08NC86 twramgjp ø replacement T ST N J 08NC85 twrgtdwa BEWICK ST S H N P Towards Heworth and N ø K 08NC84 twramgjm O South Gosforth T A L 08NC83 twramgjg OO Y L A B Occasionally there are unexpected delays to the Metro R FORTH PL L service and in these instances a bus replacement service is M 08NC82 twramgjd C NEVILLE STREET sometimes used. Passengers are advised that there may be E a delay in providing the bus replacement service. However, N 08NC96 twrgtjdm T G every effort will be made to keep delays to a minimum. -

GC002.1 Report to Gateshead Council and Newcastle City Council

GC002.1 Report to Gateshead Council and Newcastle City Council by Martin Pike BA MA MRTPI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Date: 24th February 2015 PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 (AS AMENDED) SECTION 20 REPORT ON THE EXAMINATION INTO ‘PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE’: CORE STRATEGY AND URBAN CORE PLAN FOR GATESHEAD AND NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE 2010-2030 Document submitted for examination on 21 February 2014 Examination hearings held between 3 June – 4 July and on 15 October 2014 Gateshead and Newcastle Councils’ Core Strategy and Urban Core Plan Inspector’s Report, February 2015 File Ref: PINS/M4510/429/4 - 2 - Abbreviations Used in this Report AA Appropriate Assessment AAP Area Action Plan BREEAM Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology CSUCP Core Strategy and Urban Core Plan DCLG Department for Communities and Local Government DPD Development Plan Document ELR Employment Land Review Framework National Planning Policy Framework GVA Gross Value Added HA Highways Agency IDP Infrastructure Delivery Plan LDD Local Development Document LDS Local Development Scheme LEP Local Enterprise Partnership LP Local Plan MM Main Modification MoU Memorandum of Understanding MSA Mineral Safeguarding Area NGP Newcastle Great Park PPG Planning Practice Guidance PSA Primary Shopping Area ONS Office for National Statistics RSS Regional Spatial Strategy SA Sustainability Appraisal SCI Statement of Community Involvement SCS Sustainable Community Strategy SEP North East Strategic -

Walbottle Village Character Statement and Management Plan.Pdf

Contacts: Head of Development Management Tel 0191 211 5629 Team Manager Urban Design and Conservation Tel 0191 277 7190 Write to: Development Management Environment and Regeneration Directorate Civic Centre Barras Bridge Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8PH Email: [email protected] Website: www.newcastle.gov.uk March 2011 If you need this information in another format or language, please phone the conservation team on 0191 277 7191 or email [email protected] Walbottle Village Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan Interim Planning Guidance Adopted September 2009 Updated March 2011 Walbottle Village Character Statement and Management Plan 1 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Terms of reference: conservation areas evaluation 1.2 Walbottle Village – purpose of designation, principles of character and boundaries, the sub-division of the conservation area 2 Context of Walbottle Village 2.1 Historical development 2.2 Recent changes – present situation 2.3 Landscape context 3 Character appraisal 3.1 Sub-area A: The Green 3.2 Sub-area B: Dene Terrace 3.3 Sub-area C: The Waggonway 3.4 Sub-area D: The bungalows 3.5 Walbottle Hall 4 Management plan 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Existing designations within the conservation area 4.3 Future management 4.4 Design guide by sub-area Appendix 1 Planning context of the Management Plan Appendix 2 Legislative framework of the Management Plan: planning procedures Acknowledgements Walbottle Village Character Statement and Management Plan 2 Section 1: Introduction This document was first adopted by the council as Interim Planning Guidance, at the same time as the conservation area was designated, in September 2009. -

Three Five Four Three Two Two One Three

Central Station Metro Bus and Metro tickets Area map and local bus services Transfare tickets Network One tickets to St James’ Park to Monument Map Key Nexus E Nearest bus stops for 9 minutes T 8 minutes R Road served by bus S Are you making one journey using Are you travelling for one day or one week on different onward travel W A A Bus stop (destinations listed below) ES R H Stop Stop no. Stop code TG E ATE C Metro bus replacement R different types of public transport types of public transport in Tyne and Wear? ø A 08NC95 twramgmp OAD GS N T G I J Metro line B 08NC94 twrgtdtw O The Journal K A HN ST N L I National Rail line C 08NC93 twramgmj R in Tyne and Wear? For one day’s unlimited travel on all public transport in Tyne Theatre D T M G National Cycle Network (off-road) D D 08NC92 twramgmg D Alt. J S E Tyne and Wear*, buy a Day Rover from the ticket machine. Hadrian’s Wall Path E 08NC91 twramgmd R Dance U Newcastle P A Transfare ticket allows you to buy just one ticket W A Gallery W Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright 2015. P ES F T 08NC90 twramgma V City IN TGA E Arts Arena T E K E R for a journey that involves travelling on more than For one week’s travel on all public transport in Tyne and Wear*, G 08NC87 twramgjt E OA L LA D Metro bus R H 08NC86 twramgjp U T simply choose which zones you need S one type of transport – eg Metro and bus. -

Project Orpheus Phase 1A Summary Report

Project Orpheus Phase 1A Summary Report May 2003 PHASE 1A SUMMARY REPORT Contents Section Page 1 Summary and Recommendations 3 2 Background 5 3 Overview of Process 6 4 Phase 1A Stakeholder Consultation 8 5 Corridor Selection Process 9 6 Route Assessment and Selection Process 11 Appendices Date A Working Note 1 August 2002 B Working Note 2 – Phase 1A Route Assessment November 2002 and Selection C Working Note 2 – Phase 1A Route Assessment January 2003 and Selection - UPDATE PHASE 1A SUMMARY REPORT 1 Summary The work programme for Orpheus has three distinct phases: Phase 1A - option identification and preliminary assessment Phase 1B - LRT Option Development Phase 2 – Seek Government Approval This report presents and summarises the work carried out in Phase 1A and the recommendations from the consultant team with regards the identification, appraisal and selection of potential Orpheus corridors and routes suitable for taking forward for more detailed appraisal. All the routes have been appraised in accordance with the latest Department for Transport appraisal criteria for Major Schemes (GoMMMS and updates). This will be drawn up into an Annex E submission to DfT for the preferred routes as part of the Phase 1B work programme. This information (from 1B) will also form a key element of the Outline Business Case to be put to Central Government for funding support, and a decision to proceed to Transport & Works Act Order (TWAO) proceedings. The diagram over summarises the process adopted during Phase 1A: 3 PHASE 1A SUMMARY REPORT 4 PHASE 1A SUMMARY REPORT 2 Background In 2001 Nexus published “Towards 2016”, the fifteen year strategy for the development of public transport in Tyne & Wear. -

Walbottle Dene

Exploring Hadrian’s Way Based upon the 2000 Ordnance Survey map A69 with permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O N Crown Copyright Reserved LA 076244 S S B6528 A P - HEDDON-ON Y Throckley B Walbottle Dene THE-WALL N R E Walbottle T S E W A 1 TYNE 69 A RIVERSIDE COUNTRY 1 PARK Up to 4 /2 miles / 7 km Newburn ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı A60 ı ı ı ı ı ı ı 85 ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı Wylam ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı Ryton ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı B6 ı 317 ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ııı ı ı ı ı ı ı ııı ı ı A695 ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı ı Blaydon ı ı ı ı Location of walk METRO ı CENTRE ı ı ı ı ı This 41/2 miles / 7 km walk is Contact details: packed with historical interest.