The Lessons of Qana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “Hoax” That Wasn't: the July 23 Qana Ambulance Attack

December 2006 number 1 The “Hoax” That Wasn’t: The July 23 Qana Ambulance Attack Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Claims of a Hoax ......................................................................................................2 The Hoax that wasn’t: Human Rights Watch’s in-depth investigation.......................7 Anatomy of an Attack .............................................................................................. 8 Refuting ‘Evidence’ of the ‘Hoax’ ............................................................................21 Introduction During the Israel-Hezbollah war, Israel was accused by Human Rights Watch and numerous local and international media outlets of attacking two Lebanese Red Cross ambulances in Qana on July 23, 2006. Following these accusations, some websites claimed that the attack on the ambulances “never happened” and was a Hezbollah- orchestrated “hoax,” a charge picked up by conservative commentators such as Oliver North. These claims attracted renewed attention when the Australian foreign minister stated that “it is beyond serious dispute that this episode has all the makings of a hoax.” In response, Human Rights Watch researchers carried out a more in-depth investigation of the Qana ambulance attacks. Our investigation involved detailed interviews with four of the six ambulance staff and the three wounded people in the ambulance, on-site visits to the Tibnine and Tyre Red Cross offices from which the -

MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES in LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon

Inter-Agency MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES IN LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon Calculation of the Most Vulnerable Localities is based on 251 Most Vulnerable Cadastres the following datasets: 87% Refugees 67% Deprived Lebanese 1 - Multi-Deprivation Index (MDI) The MDI is a composite index, based on deprivation level scoring of households in five critical dimensions: i - Access to Health services; Qleiaat Aakkar Kouachra ii - Income levels; Tall Meaayan Tall Kiri Khirbet Daoud Aakkar iii - Access to Education services; Tall Aabbas El-Gharbi Biret Aakkar Minyara Aakkar El-Aatiqa Halba iv - Access to Water and Sanitation services; Dayret Nahr El-Kabir Chir Hmairine ! v - Housing conditions; Cheikh Taba Machta Hammoud Deir Dalloum Khreibet Ej-Jindi ! Aamayer Qoubber Chamra ! ! MDI is from CAS, UNDP and MoSA Living Conditions and House- ! Mazraat En-Nahriyé Ouadi El-Jamous ! ! ! ! ! hold Budget Survey conducted in 2004. Bebnine ! Akkar Mhammaret ! ! ! ! Zouq Bhannine ! Aandqet ! ! ! Machha 2 - Lebanese population dataset Deir Aammar Minie ! ! Mazareaa Jabal Akroum ! Beddaoui ! ! Tikrit Qbaiyat Aakkar ! Rahbé Mejdlaiya Zgharta ! Lebanese population data is based on CDR 2002 Trablous Ez-Zeitoun berqayel ! Fnaydeq ! Jdeidet El-Qaitaa Hrar ! Michmich Aakkar ! ! Miriata Hermel Mina Jardin ! Qaa Baalbek Trablous jardins Kfar Habou Bakhaaoun ! Zgharta Aassoun ! Ras Masqa ! Izal Sir Ed-Danniyé The refugee population includes all registered Syrian refugees, PRL Qalamoun Deddé Enfé ! and PRS. Syrian refugee data is based on UNHCR registration Miziara -

Short Paper ART GOLD#35B141

ART GOLD LEBANON PROGRAMME PRESENTATION Over 80% of the Lebanese population currently lives in urbanized areas of the country, out of its estimated population of four million people. Lebanon enjoys a diverse and multi cultural society; but is a country characterized by marginalization of its peripheral areas, mainly Akkar in the North, Bekaa in the East, and South Lebanon. The South Lebanon marginalization was often exacerbated by the long-lasting occupations and wars. UNDP ART GOLD Lebanon is being implemented in the four neediest areas where the scores of poverty rates mount high, the socio-economic problems are enormous, and the convergence between deprivation and the effects of the July 2006 war took place. The ART GOLD Lebanon main aim however is to support the Lebanese national government and local communities in achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). UNDP ARTGOLD Lebanon utilizes the Local Development methodology, which relies upon the territorial networks and partnerships, which are extremely poor in the Lebanese target areas. To this end, the first steps of the programme aimed at building and strengthening the Relational and Social Capitals of the target territories. Establishing 297 Municipal, 4 Regional Working Groups (RWGs) and 22 Regional Thematic Working Groups. At the same time, regional planning exercises started in the selected sectors. The RWG requested trainings on participatory Strategic Planning, and UNDP ARTGOLD Lebanon will provide it within the forthcoming months. Governance, Local Economic Development, Social Welfare, Health, Environment, Gender Equity and Education are the UNDP ART GOLD main fields of interventions at local and national levels. To support the Regional Working Groups efforts, UNDP ARTGOLD Lebanon facilitated the set-up of a number of decentralized cooperation partnerships between Lebanese and European communities. -

A/62/883–S/2008/399 General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/62/883–S/2008/399 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 June 2008 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-second session Sixty-third year Agenda item 17 The situation in the Middle East Identical letters dated 17 June 2008 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to forward herewith the Lebanese Government’s position paper on the implementation of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006) (see annex). Also forwarded herewith are the lists of Israeli air, maritime and land violations of the blue line as compiled by the Lebanese armed forces and covering the period between 11 February and 29 May 2008 (see enclosure). I kindly request that the present letter and its annex be circulated as a document of the sixty-second session of the General Assembly under agenda item 17 and as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Caroline Ziade Chargé d’affaires, a.i. 08-39392 (E) 250608 *0839392* A/62/883 S/2008/399 Annex to the identical letters dated 17 June 2008 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Lebanese Government position paper on the implementation of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006) 17 June 2008 On the eve of the second anniversary of the adoption of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006), and in anticipation of the periodic review of the Secretary-General’s report on the implementation of the resolution, the Lebanese position on the outstanding key elements is as follows: 1. -

PRS in Lebanon - Geographic Distribution Lebanon Field February 2014

PRS in Lebanon - geographic distribution lebanon field february 2014 tartus Large numbers of Palestine refugees from Syria have taken refuge in Lebanon since the beginning of the Syrian crisis. By 14 February 2014, 52 400 PRS were recorded with the UNRWA Lebanon field office. homs ! They are living inside official camps or in other gatherings northern lebanon | 8 400 PRS and cities. 86% in beddawi & nahr el bared camps 47% beddawi camp 14% 86% halba outside 49% 51% inside 38% nahr el-bared camp ! camps camps 9% beddawi surroundings 5% tripoli city ! tripoli! ! zgharta hermel PRS are distributed throughout the 12 UNRWA official beqaa area | 8 800 PRS camps, and in other gatherings and cities in the 5 areas. chekka ehden 5% in wavel camp batrun ! gatherings 95% 5% 35% baalbeck 51% taalbaya, bar elias & zahle ! camps central lebanon | 9 200 PRS 9% other gatherings of the area 52% in burj barajneh & jbayl ! camps and gatherings in syria shatila camps 43% 57% unrwa - 29 july 2013 30% burj barajneh camp baalbak junieh !! ad nabk 22% shatila camp ! 18% sabra & burj barajneh surr. !! BEIRUT 30% other gatherings of the area [ !! !!! !! zahleh !!!! ! aley! ! bar elias ! saida area | 16 500 PRS damur 47% in ein el hillweh & beiteddine mieh mieh camps jiyeh 53% 47% chhim ! 43% ein el-hillweh saida !duma 4% mieh mieh ! jezzine ! !!! ! DAMASCUS!! ! 29% saida city ! !! ! [! ! 23% other gatherings of the area ! ! ! ! ! nabatiyeh ! ! ! ! tyre area | 9 500 PRS khiam ! 37% 63% !! 63% in the 3 official camps tyre !!!!! ! ! 40% burj shemali camp ! qana ! tebnine 13% rashidieh camp 10% el buss camp 36% other gatherings of the area naqoura ! al qunaytirah source: unrwa, 14 february 2014 unrwa, lebanon field office - emergency section - for further details, contact [email protected] or [email protected]. -

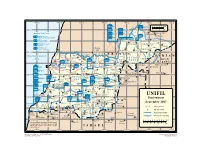

4144R18E UNIFIL Sep07.Ai

700000E 710000E 720000E 730000E 740000E 750000E 760000E HQ East 0 1 2 3 4 5 km ni MALAYSIA ta 3700000N HQ SPAIN IRELAND i 7-4 0 1 2 3 mi 3700000N L 4-23 Harat al Hart Maritime Task Force POLAND FINLAND Hasbayya GERMANY - 5 vessels 7-3 4-2 HQ INDIA Shwayya (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats, 2 auxiliaries) CHINA 4-23 GREECE - 2 vessels Marjayoun 7-2 Hebbariye (1 frigate, 1 patrol boat) Ibil 4-1 4-7A NETHERLANDS - 1 vessel as Saqy Kafr Hammam 4-7 ( ) 1 frigate 4-14 Shaba 4-14 4-13 TURKEY - 3 vessels Zawtar 4-7C (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats) Kafr Shuba ash Al Qulayah 4-30 3690000N Sharqiyat Al Khiyam Halta 3690000N tan LEBANON KHIAM Tayr Li i (OGL) 4-31 Mediterranean 9-66 4-34 SYRIAN l Falsayh SECTOR a s Bastra s Arab Sea Shabriha Shhur QRF (+) Kafr A Tura HQ HQ INDONESIA EAST l- Mine Action a HQ KOREA Kila 4-28 i Republic Coordination d 2-5 Frun a Cell (MACC) Barish 7-1 9-15 Metulla Marrakah 9-10 Al Ghajar W Majdal Shams HQ ITALY-1 At Tayyabah 9-64 HQ UNIFIL Mughr Shaba Sur 2-1 9-1 Qabrikha (Tyre) Yahun Addaisseh Misgav Am LOG POLAND Tayr Tulin 9-63 Dan Jwayya Zibna 8-18 Khirbat Markaba Kefar Gil'adi Mas'adah 3680000N COMP FRANCE Ar Rashidiyah 3680000N Ayn Bal Kafr Silm Majdal MAR HaGosherim Dafna TURKEY SECTOR Dunin BELGIUM & Silm Margaliyyot MP TANZANIA Qana HQ LUXEMBURG 2-4 Dayr WEST HQ NEPAL 8-33 Qanun HQ West BELGIUM Qiryat Shemona INDIA Houla 8-32 Shaqra 8-31 Manara Al Qulaylah CHINA 6-43 Tibnin 8-32A ITALY HQ ITALY-2 Al Hinniyah 6-5 6-16 8-30 5-10 6-40 Brashit HQ OGL Kafra Haris Mays al Jabal Al Mansuri 2-2 1-26 Haddathah HQ FRANCE 8-34 2-31 -

Syria Refugee Response ±

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON South and El Nabatieh Governorates Di s t ri b u t i o n o f t h e R e g i s t e r e d S y r i a n R e f u g e e s a t C a d a s t r a l L e v e l As of 31 May 2020 Baabda SOUTH AND EL NABATIEH Total No. of Household Registered 22,741 Total No. of Individuals Registered 99,756 Aley Mount Lebanon Chouf West Bekaa Midane Jezzine 6 Bhannine Harf Jezzine 6 Saida El-Oustani Bisri 11 Benouati Jezzine Bqosta 17 113 59 516 Aaray AAbra Saida Anane Btedine El-LeqchSabbah Hlaliye Saida Karkha Anane 69 Saida El-Qadimeh 995 Salhiyet Saida 70 Aazour 19 22 634 57 70 8,141 119 44 Bkassine Bekaa Haret Saida Majdelyoun Choualiq Jezzine 40 Mrah El-Hbasse Sfaray 935 45 356 10 Homsiye Saida Ed-Dekermane Lebaa 19 Kfar Jarra Kfar Falous Roum 11 100 Aain Ed-Delb 208 107 20 93 Miye ou Miyé290 Qaytoule 1,521 Qraiyet Saida Jensnaya A'ain El-Mir (El Establ) 5 Darb Es-Sim 190 80 70 391 Mharbiye Zaghdraiya Ouadi El-Laymoun Jezzine 6 83 10 448 Rachaya Maghdouche Tanbourit Mjaydel JezzineHassaniye Berti 505 88 22 7 3 Kfar Hatta Saida Ghaziye Qennarit Zeita 558 Kfar Melki Saida 3,687 115 50 Aanqoun 659 560 Kfar Beit 21 Jezzine Aaqtanit Kfar Chellal Jbaa En-Nabatiyeh 223 Aarab Tabbaya 245 Maamriye 6 Kfar Houne Bnaafoul 6 95 74 Najjariye 182 Aarab Ej-Jall Kfarfila Mazraat 'Mseileh 321 Erkay Houmine Et-Tahta 9 99 199 79 Aadoussiye 84 Aain Bou Souar Hajje 586 Khzaiz Sarba En-Nabatieh 37 Mlikh 10 12 Roumine 48 Aain Qana Louayzet Jezzine 10 Marj Ez-Zouhour (Haouch El-Qinnaabe) Erkay 112 92 41 Aaramta 83 Bissariye Merouaniye 79 66 Sarafand 5,182 -

Syria Refugee Response ±

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON South and El Nabatieh Governorates D i s t ri b u t i o n o f t h e R e g i s t e r e d S y r i a n R e f u g e e s a t C a d a s t r a l L e v e l As of 30 June 2017 Baabda SOUTH AND EL NABATIEH Total No. of Household Registered 26,414 Total No. of Individuals Registered 119,808 Aley Mount Lebanon Chouf West Bekaa Midane Jezzine 15 Bhannine Harf Jezzine Ghabbatiye 7 Saida El-Oustani Mazraat El-MathaneBisri 8 Benouati Jezzine Bramiye Bqosta 12 143 Taaid 37 198 573 Qtale Jezzine 9 AAbra Saida Anane 3 Btedine El-Leqch Aaray Hlaliye Saida Karkha Anane Bebé 67 Saida El-Qadimeh 1,215 Salhiyet Saida 74 Aazour 19 748 64 74 11,217 121 67 SabbahBkassine Bekaa Haret Saida Majdelyoun 23 23 Choualiq Jezzine Kfar Falous Sfaray 1,158 354 6 29 Homsiye Wadi Jezzine Saida Ed-Dekermane 49 Lebaa Kfar Jarra Mrah El-Hbasse Roum 27 11 3 Aain Ed-Delb 275 122 12 89 Qabaa Jezzine Miye ou Miyé 334 Qaytoule 2,345 Qraiyet Saida Jensnaya A'ain El-Mir (El Establ) 5 Darb Es-Sim 192 89 67 397 Rimat Deir El Qattine Zaghdraiya Mharbiye Jezzine 83 Ouadi El-Laymoun Maknounet Jezzine 702 Rachaya Maghdouche Dahr Ed-Deir Hidab Tanbourit Mjaydel Jezzine Hassaniye Haytoule Berti Haytoura 651 Saydoun 104 25 13 4 4 Mtayriye Sanaya Zhilta Sfenta Ghaziye Kfar Hatta Saida Roummanet 4,232 Qennarit Zeita 619 Kfar Melki Saida Bouslaya Jabal Toura 126 56 Aanqoun 724 618 Kfar Beit 26 Jezzine Mazraat El-Houssainiye Aaqtanit Kfar Chellal Jbaa En-NabatiyehMazraat Er-Rouhbane 184 Aarab Tabbaya 404 Maamriye 6 Kfar Houne Bnaafoul 4 Jernaya 133 93 Najjariye 187 -

Solid Waste Management City Profile

Solid Waste Management City Profile Union of Municipalities of Tyre, Lebanon District Information Number of Municipalities: 55 Names of the Municipalities in the District: Tyre, Arzoun, Bazouriyeh, Al Bayad, Al Borghliye, Al Ramadiyeh, Al Kneyseh, Al Bustan, Al Jebin, Al Hinniyeh, Al Haloussiyeh, Al Hmeyreh, Al Zaloutiyeh, Al Shatiyeh, Al Dhira, Al Kleyle, Al Majadel, Al Mansouri, Al Nafakhiyeh, Al Nakoura, Al Abassiyeh, Burj Rahal, Burj Al Shemali, Barish, Bedyas, Batouley, Jenata, Jbal Al Batm, Hanaweih, Deir Amess, Dardaghyah, Deir Keyfa, Deir Kanoun Rass, Deir Kanoun Al Naher, Zebkin, Reshkaneyna, Shameh Shehour, Shayhin, Seddikin, Srifa, Tayr Harfa, Tayr Daba, Tayr Felseyh, Toura, Aytit Alma Al Shaeb, Ain Baal, Qana Mrouhin, Maaroub, Mahrouneh, Maarakeh, Majdal Zoun, Mazraet Meshref, Yanouh, Yarin. Population: 400,000 (average between summer and winter) Area (km2): 418 km2 Climate: Tyre's climate is classified as warm and temperate. The winter months are much rainier than the summer months in Tyre. The average annual temperature is 20.2 °C. The rainfall averages 697 mm. Climate and Clean Air Coalition Municipal Solid Waste Initiative http://waste.ccacoalition.org/ 1 Main Economic Activities: Agriculture: South Lebanon is an important agricultural region, spreading from Sidon to Tyre where intensive agriculture is present in greenhouses. Greenhouse agriculture in South Lebanon covers an area of 6,277 ha, 78% of which is used for the plantation of fruits. Permanent agriculture land covers an area of 201,539 ha, 38.9% of which is used for planting olives, and 31.6% used for citrus fruits. The District of Tyre is considered one of the largest and most fertile coastal plains in the country and accounts for about 20% of the employment in the District in comparison to 8% in the whole country. -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”............................................................................. -

UNIFIL 4144 R40 Apr17 120%

700000E 710000E 730000E 750000E 760000E A 4-2 B 8-30 D 8-33 MP INDONESIA HQ Sector East HQ INDIA HQ NEPAL NEPAL MTF BRAZIL - 1 vessel SUP SPAIN INDONESIA 3700000N HQ SPAIN 7-4 INDIA (-) 3700000N HQ INDIA HQ NEPAL E 9-63 GERMANY - 1 vessel CAMBODIA Hasbayya SPAIN INDONESIA SPAIN (-) 4-23 BANGLADESH -2 vessels SUP INDIA SUP NEPAL INDIA Harat al Hart CHINA 7-3 Shwayya GREECE - 1 vessel C F G 2-31 SPAIN 4-2 8-32 9-66 ni 4-34-2 a 7-2 A NEPAL SERBIA (-) CHINA t TURKEY - 1 vessel i Hebbariye SPAIN L Marjayoun INDIA (-) INDONESIA - 1 vessel Ibil as AOR INDIA 4-7A 720000E Saqy HQ KOREA ( ROK ) Shaba HQ FRANCE INDONESIA LEBANON INDIA (-) ( ) KOREA ROK Al Qulayah 4-13 4-7C Mediterranean INDONESIA Kafr Shuba ita FRANCE HQ KOREA ( ROK ) L ni AOR SPAIN Al Khiyam 4-30 INDIA (-) 3690000N Sea Halta 3690000N FRANCE HQ INDONESIA 4-31 HQ UNIFIL KOREA ( ROK ) HQ MALAYSIA Sector AOR KOREA ( ROK ) Tayr Falsayh SUP INDONESIA 4-34 l FRANCE 9-2 a F 9-66 s KOREA ( ROK ) MALAYSIA SPAIN (-) s ITALY EAST A Shabriha Shhur l- INDONESIA Metulla a SUP FRANCE 4-28 i MRLU MALAYSIA 9-15 d SYRIAN AUSTRIA Kafr Kila a 2-5 7-1 9-15 Marrakah W 9-10 At Tayyabah 9-64 Al Ghajar FHQSU INDONESIA (-) SUP MALAYSIA AOR INDONESIA ARAB Sur (Tyre) 9-1 Addaisseh 2-1 AOR MALAYSIA Qabrikha E Mughr Shaba SRI LANKA Tulin Misgav Am REPUBLIC HQ Sector West 9-63 Tayr Zibna Kefar Gil'adi Dafna Dan Ar Rashidiyah Markaba 3 000 3680000N INDONESIA SUP ITALY (-) Jwayya Kafr Dunin 680 N MAR HaGosherim HQ ITALY AOR ITALY Khirbat Silm NEPAL INDIA Margaliyyot Dayr Qana Sector MALAYSIA D MP TANZANIA Majdal -

Lebanon Roads and Employment Project Frequently Asked Questions

Lebanon Roads and Employment Project Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is the Roads and Employment Project (REP)? The Lebanon Roads and Employment Project (REP) is a US$200 million project that aims to improve transport connectivity along select paved road sections and create short-term jobs for the Lebanese and Syrians. The REP was approved by the World Bank (WB) Board of Executive Directors in February 2017 and ratified by the Lebanese Parliament in October 2018. The Project is co-financed by a US$45.4 million grant contribution from the Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF) which provides concessional financing to middle income countries hosting large numbers of refugees at rates usually reserved for the poorest countries. The project is implemented by the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) in coordination with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT), noting that all the roads under the REP are under the jurisdiction of the MPWT. In response to the devastating impact of the economic and financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic on the agriculture sector and food security, the project was restructured in March 2021: a third objective was added and a US$10 million reallocation approved to provide direct support to farmers engaged in crop and livestock production (Please refer to questions # 18 to 26) 2. What are the Components of the Roads and Employment Project? The REP originally had three components. Following its restructuring in March 2021, a fourth component was added to address the impact of the