Also Known As Jaintia Or Synteng, Though Pnar Is the Term Pre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

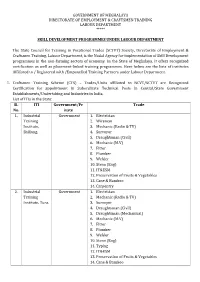

Skill Development Programmes Under Labour Department

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA DIRECTORATE OF EMPLOYMENT & CRAFTSMEN TRAINING LABOUR DEPARTMENT ***** SKILL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES UNDER LABOUR DEPARTMENT The State Council for Training in Vocational Trades (SCTVT) Society, Directorate of Employment & Craftsmen Training, Labour Department, is the Nodal Agency for implementation of Skill Development programmes in the non-farming sectors of economy in the State of Meghalaya. It offers recognized certification as well as placement-linked training programmes. Here below are the lists of institutes Affiliated to / Registered with /Empanelled Training Partners under Labour Department. 1. Craftsmen Training Scheme (CTS) – Trades/Units affiliated to NCVT/SCTVT are Recognized Certification for appointment in Subordinate Technical Posts in Central/State Government Establishments/Undertaking and Industries in India. List of ITIs in the State: Sl. ITI Government/Pr Trade No. ivate 1. Industrial Government 1. Electrician Training 2. Wireman Institute, 3. Mechanic (Radio & TV) Shillong. 4. Surveyor 5. Draughtsman (Civil) 6. Mechanic (M.V) 7. Fitter 8. Plumber 9. Welder 10. Steno (Eng) 11. IT&ESM 12. Preservation of Fruits & Vegetables 13. Cane & Bamboo 14. Carpentry 2. Industrial Government 1. Electrician Training 2. Mechanic (Radio & TV) Institute, Tura. 3. Surveyor 4. Draughtsman (Civil) 5. Draughtsman (Mechanical) 6. Mechanic (M.V) 7. Fitter 8. Plumber 9. Welder 10. Steno (Eng) 11. Typing 12. IT&ESM 13. Preservation of Fruits & Vegetables 14. Cane & Bamboo 15. Carpentry 3. Industrial Government 1. Dress Making Training 2. Hair & Skin Institute 3. Dress Making (Advanced) (Women), Shillong 4. Govt. Government 1. Wireman Industrial 2. Plumber Training 3. Mason (Building Constructor) Institute, Sohra 4. Painter General 5. Office Assistant cum Computer Operator 5. -

Mon-Khmer Studies Volume 41

Mon-Khmer Studies VOLUME 42 The journal of Austroasiatic languages and cultures Established 1964 Copyright for these papers vested in the authors Released under Creative Commons Attribution License Volume 42 Editors: Paul Sidwell Brian Migliazza ISSN: 0147-5207 Website: http://mksjournal.org Published in 2013 by: Mahidol University (Thailand) SIL International (USA) Contents Papers (Peer reviewed) K. S. NAGARAJA, Paul SIDWELL, Simon GREENHILL A Lexicostatistical Study of the Khasian Languages: Khasi, Pnar, Lyngngam, and War 1-11 Michelle MILLER A Description of Kmhmu’ Lao Script-Based Orthography 12-25 Elizabeth HALL A phonological description of Muak Sa-aak 26-39 YANIN Sawanakunanon Segment timing in certain Austroasiatic languages: implications for typological classification 40-53 Narinthorn Sombatnan BEHR A comparison between the vowel systems and the acoustic characteristics of vowels in Thai Mon and BurmeseMon: a tendency towards different language types 54-80 P. K. CHOUDHARY Tense, Aspect and Modals in Ho 81-88 NGUYỄN Anh-Thư T. and John C. L. INGRAM Perception of prominence patterns in Vietnamese disyllabic words 89-101 Peter NORQUEST A revised inventory of Proto Austronesian consonants: Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic Evidence 102-126 Charles Thomas TEBOW II and Sigrid LEW A phonological description of Western Bru, Sakon Nakhorn variety, Thailand 127-139 Notes, Reviews, Data-Papers Jonathan SCHMUTZ The Ta’oi Language and People i-xiii Darren C. GORDON A selective Palaungic linguistic bibliography xiv-xxxiii Nathaniel CHEESEMAN, Jennifer -

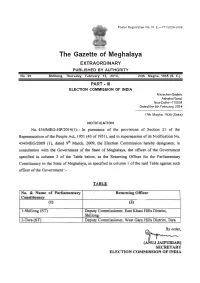

Part-III Extra 2014.Pmd

Postal Registration No. N. E.—771/2006-2008 The Gazette of Meghalaya EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 39 Shillong, Thursday, February 13, 2014, 24th Magha, 1935 (S. E.) PART - III ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi—110001 Dated the 6th February, 2014 ---------------------------------------------- 17th Magha, 1935 (Saka) NOTIFICATION 128 THE GAZETTE OF MEGHALAYA, (EXTRAORDINARY) FEBRUARY 13, 2014 [PART-III PART - III ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi—110001 Dated the 6th February, 2014 ---------------------------------------------- 17th Magha, 1935 (Saka) NOTIFICATION PART-III] THE GAZETTE OF MEGHALAYA, (EXTRAORDINARY) FEBRUARY 13, 2014 129 SHILLONG: Printed and Published by the Director, Printing and Stationery, Meghalaya, Shillong. (Extraordinary Gazette of Meghalaya) No. 77 - 700+100—18-2-2014. website:- http://megpns.gov.in/gazette/gazette.asp Postal Registration No. N. E.—771/2006-2008 The Gazette of Meghalaya EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 42 Shillong, Thursday, February 13, 2014, 24th Magha, 1935 (S. E.) PART-IV GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA DISTRICT COUNCIL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR ——— NOTIFICATIONS The 13th February, 2014. No.DCA.17/2014/34.—In pursuance of Rule 137 (1) of the Assam and Meghalaya Autonomous Districts (Constitution of District Councils) Rules 1951, as amended the following names of Contesting Candidates for the General Elections, 2014 to the Constituencies from 1 to 29 of the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council together with the party affiliattion and the Symbol allotted to each candidate are published for general information. [FORM 7A] List of Contesting Candidates [See Rule 137 (1)] Election to the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council 2014 from 1-Jirang Constituency Sl. -

House No 5 | Amrabati Path | Christian Basti | GS

ASSAM HOLIDAYS – 09 Duration - 04 Nights | 05 Days Destinations - Shillong (2N), Cherrapunji (2N) Day Wise Itinerary Day 01: Guwahati – Shillong (100 KM / 3 HRS) Welcome to Guwahati. Meet and be assisted by our representative at the airport/Railway Station. Proceed to Shillong, also called 'Scotland of the East". Reach the majestic Umium Lake (Barapani). You may do the water sports here (Optional). On arrival at Shillong, check in at your hotel. Evening you can visit Police Bazaar which the biggest local market. Overnight stay in Shillong. Day 02: Shillong - Dawki - Mawlynnong Village - Shillong After breakfast visit Mawlynnong Village the cleanest village in India. This cute and colorful little village is known for its cleanliness. It is situated 90 kms. from Shillong and besides the picturesque village, offers many interesting sights such as the Living Root Bridge and another strange natural phenomenon of a boulder balancing on another rock. Visit Dawki, It is along the Indo-Bangladesh border. You can enjoy boating in the crystal clear waters of the Umgnot River Evening return to Shillong. Visit Elephanta Falls and Shillong Peak for some breathtaking views.. Overnight in Shillong. Day 03: Shillong - Cherrapunji (65 KM | 1.5 Hrs) Get up early today to enjoy the mesmerizing mornings of Shillong. After early breakfast drive to Cherrapunji, this is the wettest place in the world. Visit Eco Park, Dainthlen Falls, Nohkalikai Falls, Nohsngithiang Falls (Seven Sisters Falls), Mawsmai Cave, Thangkharang Park. Overnight stay in Cherrapunji. Day 04: Cherrapunji After breakfast we proceed for a full day trekking to the Double Decker Living Root Bridge at Nongriat Village. -

T .( / '\~~~\ LAW(A)DEPARTMENT Ffc,

;:<-.~--~-& -(:·:.~.," / ' '.) --w-•---......(:t,. , ,, /~:< ~~~· .~-~ -- · .., ·~~--~ GOVERNMENTOFMEQHALAYA t .( / '\~~~\ LAW(A)DEPARTMENT ffc, .. \'==· {;u;' , ,n [U .\~ 1 -~\ !\ •..~ ! n q t;1· i\ jf~·Tr ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR ;\ · :· \ L ' -!$.I \,;·:; :_ \ / ··t(tit fJ (.;I \\f...' \" r.., }- ~.'h NOTIFICATION "'<;:. "" . .-$>.~, ~~: ··· Dated, Shillong the 27'h April, 2015. :::::-....::---..--: _ ...-;; No. U(A) 77/2000/PtJ90 - In exercise qf the powers conferred under rule 1-A of the Rules for Administration ofJustice and Police in<ttri I(hasi and :Taintia Hills, 1937 and further under sub-section (1) of Section 2 of the rteghalaya Autonomous Districts Administration of Justice Act (Assam Act XIV of 1960 as adapted ao(J amended by Megha'laya) read with paragraph 5 of the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, the Gdvemor of Meghalaya, with-the approval of the Hon'ble High Court of Meghalaya, is pleased to appoint Smti B. Mawrie, District & Sessions Judge, Jowai as the Additional Deputy Commissioner, West Jaintia Hills District for the trial of all offences punishable with death, imprisonment for life or imprisonment for a term of not less than five years under the Indian Penal Code or under any other Law for the time being applicable to the District and also to hear all Civil and Criminal revisions, appeals, etc. from, the decisions of the Assistants to the Deputy Commissioners within the said District and the Governor is further pleased to direct that su((h District & Sessions Judge as Additional Deputy Commissioner shall for the purpose aforesaid, exercise all the Judicial powers of the Deputy Commissioner within the said District excluding Amlatem (Civil) Sub-division with immediate effect. -

Incredible Results in IAS 2013 5 Ranks 62 Ranks in Top 50 Ranks in the Final List

RESULTS Incredible results in IAS 2013 5 Ranks 62 Ranks in Top 50 Ranks in the final list Rank 9 Rank 12 Rank 23 Rank 40 Rank 46 Divyanshu Jha Neha Jain Prabhav joshi Gaurang Rathi Udita Singh We broke our past record in IAS 2014 6 Ranks 12 Ranks 83 Ranks in Top 50 in Top 100 Overall Selections Rank 4 Rank 5 Rank 16 Rank 23 Rank 28 Rank 39 Vandana Rao Suharsha Bhagat Ananya Das Anil Dhameliya Kushaal Yadav Vivekanand T.S We did it again in IAS 2015 5 Ranks 14 Ranks 162 Ranks in Top 50 in Top 100 In The Final List Rank 20 Rank 24 Rank 25 Rank 27 Rank 47 Vipin Garg Khumanthem Chandra Pulkit Garg Anshul Diana Devi Mohan Garg Agarwal And we’ve done it yet again in IAS 2016 8 Ranks 18 Ranks 215 Ranks in Top 50 in Top 100 In The Final List Rank 2 Rank 5 Rank 12 Rank 30 Rank 32 Anmol Sher Abhilash Tejaswi Prabhash Avdhesh Singh Bedi Mishra Rana Kumar Meena And we’ve done it yet again in IAS 2017 5 Ranks 34 Ranks 236 Ranks in Top 10 in Top 100 In The Final List Rank 3 Rank 6 Rank 8 Rank 9 Rank 10 Sachin Koya sree Anubhav Saumya Abhishek Gupta Harsha Singh Sharma Surana Ashima Abhijeet Varjeet Keerthi Utsav Gaurav Abhilash Vikramaditya Vishal Mittal Sinha Walia Vasan V Gautam Kumar Baranwal Singh Malik Mishra Rank-12 Rank-19 Rank-21 Rank-29 Rank-33 Rank-34 Rank-44 Rank-48 Rank-49 Sambit Bodke Akshat Jagdish Hirani Swapneel Jyoti Pushp Amol Mishra Digvijay Govind Kaushal Chelani Adityavikram Paul Sharma Lata Srivastava Rank-51 Rank-54 Rank-55 Rank-57 Rank-60 Rank-64 Rank-75 Rank-80 Rank-83 Prateek Amilineni Sangh Rahul Kathawate Vaibhava Videh Plash -

CONFERENCE REPORT the 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE of the NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY 12-14 February 2010, Shillong, Meghalaya, India

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 33.1 — April 2010 CONFERENCE REPORT THE 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY 12-14 February 2010, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Stephen Morey La Trobe University The 5th conference of the North East Indian Linguistics Society (NEILS) was held from 12th to 14th February 2010 at the Don Bosco Institute (DBI), Kharguli Hills, Guwahati, Assam. The conference was preceded by a two day workshop, hosted by Gauhati University,1 but also held at DBI. NEILS is grateful to the Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, for providing funds to assist in the running of the workshops and conference. The two day workshop was in two parts: one day on using the Toolbox program, run by Virginia and David Phillips of SIL; and one day on working with tones, presented by Mark W. Post, Stephen Morey and Priyankoo Sarmah. Both workshops were well-attended and participatory in nature. The tones workshop included an intensive session of the Boro language, with five native speakers, all students of the Gauhati University Linguistics Department, providing information on their language and interacting with the participants. The conference itself began on 12th February with the launch of Morey and Post (2010) North East Indian Linguistics, Volume 2, performed by Nayan J. Kakoty, Resident Area Manager of Cambridge University Press India. This volume contains peer-reviewed and edited papers from the 2nd NEILS conference, held in 2007, representing NEILS’ commitment to the publication of the conference papers. A notable feature of the conference was the presence of seven people, from India, Burma, Australia and Germany, working on the Tangsa group of languages spoken on the India-Burma border. -

Mon-Khmer Studies Volume 41

MMoonn--KKhhmmeerr SSttuuddiieess VOLUME 43 The journal of Austroasiatic languages and cultures 1964—2014 50 years of MKS Copyright vested with the authors Released under Creative Commons Attribution License Volume 43 Editors: Paul Sidwell Brian Migliazza ISSN: 0147-5207 Website: http://mksjournal.org Published by: Mahidol University (Thailand) SIL International (USA) Contents Issue 43.1 Editor’s Preface iii Michel FERLUS Arem, a Vietic Language. 1-15 Hiram RING Nominalization in Pnar. 16-23 Elizabeth HALL Impact of Tai Lue on Muak Sa-aak phonology. 24-30 Rujiwan LAOPHAIROJ Conceptual metaphors of Vietnamese taste terms. 31-46 Paul SIDWELL Khmuic classification and homeland. 47-56 Mathias JENNY Transitivity and affectedness in Mon. 57-71 J. MAYURI, Karumuri .V. SUBBARAO, Martin EVERAERT and G. Uma Maheshwar RAO Some syntactic aspects of lexical anaphors in select Munda Languages. 72-83 Stephen SELF Another look at serial verb constructions in Khmer. 84-102 V. R. RAJASINGH Interrogation in Muöt. 103-123 Issue 43.2 Suwilai PREMSRIRAT, Kenneth GREGERSON Fifty Years of Mon-Khmer Studies i-iv Anh-Thư T. NGUYỄN Acoustic correlates of rhythmic structure of Vietnamese narrative speech. 1-7 P. K. Choudhary Agreement in Ho 8-16 ii Editors’ Preface The 5th International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics (ICAAL5) was held at the Australian National University (ANU) over September 4-5, 2013. The meeting was run in conjunction with the 19th Annual Himalayan Languages Symposium (HLS19), organised locally by Paul Sidwell and Gwendolyn Hyslop. The meetings were made possible by support provided by the following at ANU: Department of Linguistics, College of Asia and the Pacific Research School of Asia Pacific School of Culture, History and Language Tibetan Cultural Area Network Some 21 papers were read over two days at the ICAAL meeting, nine of which have found their way into this special issue of MKS. -

Jaintia Hills District, Meghalaya

Technical Report Series: D No: 49/2011-12 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET JAINTIA HILLS DISTRICT, MEGHALAYA North Eastern Region Guwahati September, 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET JAINTIA HILLS DISTRICT, MEGHALAYA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl ITEMS STATISTICS No. 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (Sq km) 3819 ii) Administrative Divisions Number of Blocks 5 a) Thadlaskein b) Laskein c) Amlarem d) khliehriat e) Saipung Number of Villages 537 iii)Population ((Provisional) (2011 census) Total Population 3,92,852 (Decadal Growth 2001-2011 31.34%) Rural Population 3,64,369 (Decadal Growth 2001-2011 32.96%) Urban Population 28,483 (Decadal Growth 2001-2011 13.67%) iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 4173 Source: Dept. of Agriculture, Meghalaya Rain gauge station: Rymphum seed farm, Jowai 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Denudational High & Low Hills, dissected plateau with deep gorges. Major Drainages Myngngot (Umngot), Myntdu, Wah Prang, Wah Lukha, Wah Simlieng and Kopili 3. LAND USE (Sq Km) 2010-11 a) Forest area 1540.59 b) Net area sown 351.75 c)Total Cropped area 355.35 4. MAJORS SOIL TYPES a) Red loamy b) Laterite c) Alluvial 5. AREA UNDER PRINICIPAL CROPS (as Kharif: Rice:123.24, Maize:30.68, Oilseeds:4.1 on 2010-11, in sq Km) Rabi : Rice:0.50, Millets:1.62, Pulses:0.77, Source: Directorate of Agriculture, Meghalaya. Oilseeds:0.89 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES a. Surface water (sq km) 45 b. Ground water (sq km) Nil 7. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER (as on 31.3.2013) MONITORING WELLS of CGWB No. -

Request for Proposal

BID DOCUMENT NO.MIS/NeGP/CSC/08 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL FOR SELECTION OF SERVICE CENTRE AGENCIES TO SET UP, OPERATE AND MANAGE TWO HUNDRED TWENTY FIVE (225) COMMON SERVICES CENTERS IN THE STATE OF MEGHALAYA VOLUME 3: SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION TO BIDDERS Date: _________________ ISSUED BY MEGHALAYA IT SOCIETY NIC BUILDING, SECRETARIAT HALL SHILLONG-793001 On Behalf of INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA Content 1. List of Websites of Megahalya 2. List of BSNL rural exchange 3. Ac Neilsen Study on Meghalaya (including Annexure-I & Annexure-II) List of BSNL Rural Exchanges Annexure -3 Exchange details Sl.No Circle SSA SDCA SDCC No. of Name Type Cap Dels villages covered 1 NE-I Meghalaya Cherrapunji Cherrapunji Cherrapunji MBMXR 744 513 2 NE-I Meghalaya Cherrapunji Cherrapunji Laitryngew ANRAX 248 59 3 NE-I Meghalaya Dawki Dawki Dawki SBM 360 356 4 NE-I Meghalaya Dawki Dawki Amlaren 256P 152 66 5 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Phulbari SBM 1000 815 6 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Rajabala ANRAX 312 306 7 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Selsella 256P 152 92 8 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Holidayganj 256P 152 130 9 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Tikkrikilla ANRAX 320 318 10 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai 8th Mile ANRAX 248 110 11 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Kyndongtuber ANRAX 152 89 12 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Nartiang ANRAX 152 92 13 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Raliang MBMXR 500 234 14 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Shanpung ANRAX 248 236 15 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Ummulong MBMXR 500 345 16 NE-I Meghalaya Khileiriate -

Annual Final Report of Tourism Survey for the State of Meghalaya (April 2014-March 2015)

Annual Final Report of Tourism Survey for the State of Meghalaya (April 2014-March 2015) Submitted by: Datamation Consultants Pvt.Ltd, Submitted to: Plot no. 361, Patparganj Ministry of Tourism (Market Research Industrial Area, New Delhi- Division Govt. of India) 110092 Telephone: 011-22158819 Fax: 011-22158819 0 | P a g e Ministry of Tourism, Government of India Annual Report Meghalaya ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We are thankful to the Ministry of Tourism, Government of India for assigning to the Datamation Group, New Delhi the prestigious study for conducting “Tourism Survey for the State of Meghalaya”. We would also like to acknowledge cooperation, support and input we received from the Market Research Division, Ministry of Tourism-Govt. of India & Meghalaya Tourism for ensuring successful completion of the survey which was carried out in all districts of Meghalaya. We would like to thank first and foremost Secretary Ms Rashmi Verma , Director General Mr Satyajeet Rajan Shri S M Mahajan- Additional Director General, Dr. R.K. Bhatnagar -Ex- Additional Director General (MR), Ms. Mini Prasanna Kumar- Director, Ms. Neha Srivastava - Deputy Director (MR), Mr. Shailesh Kumar - Deputy Director (MR) for providing us necessary guidance and periodical support for conducting the survey. We would also like to thank Mr. S.K. Mohanta, Programmer - MR and other team members for providing us support and help. The present report is an outcome of dedicated commitment to the field survey of the research investigators and cooperation received from the officials of Meghalaya Tourism. We would like to thank Hon. Secretary, Meghalaya, current Managing Director as well as previous Managing Directors of the Meghalaya Tourism Development Corporation Ltd. -

Download Itinerary

Starting From Rs. 14102.4 (Per Person twin sharing) PACKAGE NAME : No 11 North East Triangle PRICE INCLUDE Hotel,Only Breakfast,Activity,Sightseeing,Car On Disposal Day : 1 Guwahati - Kaziranga National Park (230 KM 4.5 Hrs) Welcome to Guwahati. Meet and be assisted by our representative at the airport/Railway Station. Transfer to Kaziranga National Park, the home of the One Horn Indian Rhinoceros. Check in at your hotel/Lodge/resort. Evening you may visit Orchid Park and the nearby Tea Plantations. Overnight stay at Kaziranga National Park. HOTEL Florican Lodge SIGHTSEEING Orchid Park Day : 2 Kaziranga National Park Early morning explore Kaziranga National Park on back of elephant. Apart from world's endangered One Horn Indian Rhinoceros, the Park sustains half the world's population of genetically pure Wild Water Buffaloes, over 1000 Wild elephants and perhaps the densest population of Royal Bengal Tiger anywhere. Kaziranga National Park is also a bird watcher's paradise and home to some 500 species of Birds. The Crested Serpent Eagle, Palla's Fishing Eagle, Greyheaded Fishing Eagle, Swamp Partridge, Bar-headed goose, whistling Teal, Bengal Florican, Storks, Herons and Pelicans are some of the species found here. We will return to the resort for breakfast. Afternoon we proceed for a jeep safari. Evening come back to the hotel. Overnight stay at Kaziranga National Park. HOTEL Florican Lodge SIGHTSEEING Elephant Safari (Kaziranga), Jeep Safari (Kaziranga) Day : 3 Kaziranga National Park– Shillong (280 Km | 6 Hrs) After breakfast drive to Shillong, also called 'Scotland of the East". Reach the majestic Umium Lake (Barapani).