Fiction and Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Watermen Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE WATERMEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Easter | 416 pages | 21 Jun 2016 | Quercus Publishing | 9780857380562 | English | London, United Kingdom The Watermen PDF Book Read more Edit Did You Know? Pascoe, described as having blond hair worn in a ponytail, does have a certain Aubrey-ish aspect to him - and I like to think that some of the choices of phrasing in the novel may have been little references to O'Brian's canon by someone writing about the same era. Error rating book. Erich Maria Remarque. A clan of watermen capture a crew of sport fishermen who must then fight for their lives. The Red Daughter. William T. Captain J Ashley Myers This book is so engrossing that I've read it in the space of about four hours this evening. More filters. External Sites. Gripping stuff written by local boy Patrick Easter. Release Dates. Read it Forward Read it first. Dreamers of the Day. And I am suspicious of some of the obscenities. This thriller starts in medias res, as a girl is being hunter at night in the swamp by a couple of hulking goons in fishermen's attire. Lists with This Book. Essentially the plot trundles along as the characters figure out what's happening while you as the reader have been aware of everything for several chapters. An interesting look at London during the Napoleonic wars. Want to Read saving…. Brilliant book with a brilliant plot. Sign In. Luckily, the organiser of the Group, Diane, lent me her copy of his novel to re I was lucky enough to meet the Author, Patrick Easter at the Hailsham WI Book Club a month or so ago, and I have to say that the impression I had gained from him at the time was that he seemed to have certainly researched his subject well, and also had personal experience in policing albeit of the modern day variety. -

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto 1 The Sadleir-Black Collection 2 2 The Microfilm Collection 7 3 Gothic Origins 11 4 Gothic Revolutions 15 5 The Northanger Novels 20 6 Radcliffe and her Imitators 23 7 Lewis and her Followers 27 8 Terror and Horror Gothic 31 9 Gothic Echoes / Gothic Labyrinths 33 © Peter Otto and Adam Matthew Publications Ltd. Published in Gothic Fiction: A Guide, by Peter Otto, Marie Mulvey-Roberts and Alison Milbank, Marlborough, Wilt.: Adam Matthew Publications, 2003, pp. 11-57. Available from http://www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/gothic_fiction/Contents.aspx Deposited to the University of Melbourne ePrints Repository with permission of Adam Matthew Publications - http://eprints.unimelb.edu.au All rights reserved. Unauthorised Reproduction Prohibited. 1. The Sadleir-Black Collection It was not long before the lust for Gothic Romance took complete possession of me. Some instinct – for which I can only be thankful – told me not to stray into 'Sensibility', 'Pastoral', or 'Epistolary' novels of the period 1770-1820, but to stick to Gothic Novels and Tales of Terror. Michael Sadleir, XIX Century Fiction It seems appropriate that the Sadleir-Black collection of Gothic fictions, a genre peppered with illicit passions, should be described by its progenitor as the fruit of lust. Michael Sadleir (1888-1957), the person who cultivated this passion, was a noted bibliographer, book collector, publisher and creative writer. Educated at Rugby and Balliol College, Oxford, Sadleir joined the office of the publishers Constable and Company in 1912, becoming Director in 1920. He published seven reasonably successful novels; important biographical studies of Trollope, Edward and Rosina Bulwer, and Lady Blessington; and a number of ground-breaking bibliographical works, most significantly Excursions in Victorian Bibliography (1922) and XIX Century Fiction (1951). -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover -

A Study of Hypernarrative in Fiction Film: Alternative Narrative in American Film (1989−2012)

Copyright by Taehyun Cho 2014 The Thesis Committee for Taehyun Cho Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Study of Hypernarrative in Fiction Film: Alternative Narrative in American Film (1989−2012) APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Charles R. Berg Thomas G. Schatz A Study of Hypernarrative in Fiction Film: Alternative Narrative in American Film (1989−2012) by Taehyun Cho, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication To my family who teaches me love. Acknowledgements I would like to give special thanks to my advisor, Professor Berg, for his intellectual guidance and warm support throughout my graduate years. I am also grateful to my thesis committee, Professor Schatz, for providing professional insights as a scholar to advance my work. v Abstract A Study of Hypernarrative in Fiction Film: Alternative Narrative in American Film (1989-2012) Taehyun Cho, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2014 Supervisor: Charles R. Berg Although many scholars attempted to define and categorize alternative narratives, a new trend in narrative that has proliferated at the turn of the 21st century, there is no consensus. To understand recent alternative narrative films more comprehensively, another approach using a new perspective may be required. This study used hypertextuality as a new criterion to examine the strategies of alternative narratives, as well as the hypernarrative structure and characteristics in alternative narratives. Using the six types of linkage patterns (linear, hierarchy, hypercube, directed acyclic graph, clumped, and arbitrary links), this study analyzed six recent American fiction films (between 1989 and 2012) that best represent each linkage pattern. -

Film Genre and Its Vicissitudes: the Case of the Psychothriller 1

FILM GENRE AND ITS VICISSITUDES: THE CASE OF THE PSYCHOTHRILLER 1 Virginia Luzón Aguado Universidad de Zaragoza This paper is the result of an exploration into the contemporary psychothriller and its matrix genre, the thriller. It was inspired by the lack of critical attention devoted to this type of film, so popular with the audience yet apparently a thorn in the critics' side. The main aim of this paper is therefore to contribute a small piece of criticism to fill this noticeable gap in film genre theory. It begins with a brief overview of contemporary film genre theory, which provides the background for a vindication of the thriller as a genre and specifically of the psychothriller as a borderline sub-generic category borrowing features from both the thriller and the horror film. When I first started work on this paper I realised how difficult it was to find theoretical material on the thriller. Certain genre critics actually avoided the term thriller altogether and others mentioned it but often seemed to be either unsure about it or simultaneously, and rather imprecisely, referred to different types of films, such as detective films, police procedural films, political thrillers, courtroom thrillers, erotic thrillers and psychothrillers, to name but a few. But the truth of the matter is that "the thriller" as such has rarely been analysed in books or articles devoted to the study of genre and when it has, one can rarely find anything but a few short paragraphs dealing with it. Yet, critical work devoted to other acknowledged and well-documented genres such as melodrama, comedy, film noir, horror, the western, the musical or the war film is easily accessible. -

A Variety of Thrills

A Variety of Thrills Thrillers and different ways of approaching them K.A. Kamphuis, 3654621 Semester 2, 2012-2013 January 25 2013 J.S. Hurley Film Genres, Thrillers Abstract Thriller is a broad genre. This genre is constructed by the use of different people involved in the movie process; the producers and advertisers, critics and consumers. They all have different reasons to call a thriller a thriller. I did a discourse analysis on three movies to see whether the use of the term “thriller” is used by all this parties in the same way and how this will construct the genre. The three movies in that are analysed are The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011), Black Swan (2010) and Hide and Seek (2005). Index Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 Discursive Approaches ....................................................................................................... 5 Producers ....................................................................................................................... 5 Advertisers ..................................................................................................................... 7 Critics ............................................................................................................................. 8 Consumers ................................................................................................................... 10 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... -

Graphica Fiction Poetry Crime/Thriller

poetry Air Salt A Trauma Mémoire as a Result of the Fall Ian Kinney Ian Kinney fell seven stories, and he survived. Here, he (un)writes his hospitalization and recovery, using poetry as neuro-rehabilitation. A memoir by an amnesiac, this collection cuts and reassembles splintered narratives into a profound new whole. fiction crime/thriller press.ucalgary.ca Advice for Taxidermists and Amateur Beekeepers This Has Nothing to Do With You Collision Course Baddie One Shoe Erin Emily Ann Vance Lauren Carter Douglas Morrison Natalie Meisner The sudden death of Margot Morris and her two young daughters Melony Barnett’s mother has committed a murder that changed Back in Canada after a harrowing vacation gone wrong, Michael You know that voice in your head that cuts through it? The tough in a house fire sends shock waves through a small rural everything. As Mel struggles to heal from the loss created by this Barrett tries to put all thought of Ukraine from his mind. This bitch who rescues you in a broken down car. The dyke who takes community. Margot’s three surviving siblings are left to wonder crime, she begins to uncover layers of secrets about her family. would be a little easier if a million dollars had not just popped a punch. The queer who takes down the hypocrite. Her name is if Margot’s death was an accident or murder. freehand-books.com into his bank account. A mistake, or a message? Baddie One Shoe! stonehousepublishing.ca stonehousepublishing.ca The Towers of Babylon frontenachouse.com Arctic Smoke Michelle Kaeser The Red Chesterfield let us not think of them as barbarians Randy Nikkel Schroeder Embracing the anxieties of urban life, this darkly funny novel Wayne Arthurson Peter Midgley Forced to rejoin his bandmates, ageing punk Lor Kowalski is tracks four hapless Millennials in a world where housing prices How far would you go to issue a bylaw ticket? This is a delightful, A bold narrative of love, migration, and war hewn from the stones dragged north under the spell of an ad for an Arctic tour. -

A Study of Gothic Elements in Shirley Jackson's

© 2019 JETIR December 2019, Volume 6, Issue 12 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A STUDY OF GOTHIC ELEMENTS IN SHIRLEY JACKSON’S “WE HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN THE CASTLE” Dr. Smita Mishra Assistant Professor Dept. of Basic Sciences & Humanities, PSIT, Bhauti, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. ABSTRACT: The term ‘Gothic’ was used as a medieval style of intricate architecture and ornate around the 12th century which also originated in France. It was in the Romantic age in the late 18th century when this was actually applied to literature. Gothic literature was mentioned in 1764 for the first time, in English writer Horace Walpole’s, ‘The castle of Otranto’. A Gothic novel consists of supernatural events and combine elements from horror and romanticism. It can also be explained in a way that it deals with such elements or happening in nature which cannot be explained easily or over which humans have no control. It’s most common plots are mystery and suspense. Gothic literature contains characteristics like horror, mystery, magic, clanking of chains, ghosts, supernatural activities, dark elements, dark castles to create an uncanny effect. Over the period of time gothic elements have shifted from the outer aspect to an inner aspect of human psyche. Shirley Jackson’s novel ‘We have always lived in the castle’ depicts the power of gothic through the hands of a master artisan. My paper will introduce the background of Gothic fiction in Literature and will also explore the elements used in crafting this novel which makes it a remarkable work in the genre of mystery, thriller and gothic. -

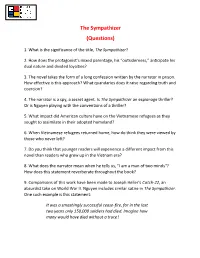

The Sympathizer (Questions)

The Sympathizer (Questions) 1. What is the significance of the title, The Sympathizer? 2. How does the protagonist’s mixed parentage, his “outsiderness,” anticipate his dual nature and divided loyalties? 3. The novel takes the form of a long confession written by the narrator in prison. How effective is this approach? What quandaries does it raise regarding truth and coercion? 4. The narrator is a spy, a secret agent. Is The Sympathizer an espionage thriller? Or is Nguyen playing with the conventions of a thriller? 5. What impact did American culture have on the Vietnamese refugees as they sought to assimilate in their adopted homeland? 6. When Vietnamese refugees returned home, how do think they were viewed by those who never left? 7. Do you think that younger readers will experience a different impact from this novel than readers who grew up in the Vietnam era? 8. What does the narrator mean when he tells us, "I am a man of two minds"? How does this statement reverberate throughout the book? 9. Comparisons of this work have been made to Joseph Heller's Catch-22, an absurdist take on World War II. Nguyen includes similar satire in The Sympathizer. One such example is this statement: It was a smashingly successful cease-fire, for in the last two years only 150,000 soldiers had died. Imagine how many would have died without a truce! Can you find other examples where the author employs similar satiric wit? What affect does such a stylistic device have on your reading? Does the black humor lessen the horror of the war, or draw more attention to it? 10. -

Evergreen Review on Film, Mar 16—31

BAMcinématek presents From the Third Eye: Evergreen Review on Film, Mar 16—31 Marking the release of From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Film Reader, a new anthology of works published in the seminal counterculture journal, BAMcinématek pays homage to a bygone era of provocative cinema The series kicks off with a week-long run of famed documentarian Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory in a new restoration The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Feb 17, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Wednesday, March 16, through Thursday, March 31, BAMcinématek presents From the Third Eye: Evergreen Review on Film. Founded and managed by legendary Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset, Evergreen Review brought the best in radical art, literature, and politics to newsstands across the US from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. Grove launched its film division in the mid-1960s and quickly became one of the most important and innovative film distributors of its time, while Evergreen published incisive essays on cinema by writers like Norman Mailer, Amos Vogel, Nat Hentoff, Parker Tyler, and many others. Marking the publication of From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, edited by Rosset and critic Ed Halter, this series brings together a provocative selection of the often controversial films that were championed by this seminal publication—including many distributed by Grove itself—vividly illustrating how filmmakers worked to redefine cinema in an era of sexual, social, and political revolution. The series begins with a week-long run of a new restoration of Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory (1948/1964), “the most ambitious leftist film made in the US” (J. -

Ebook Download Razor : Fantasy Thriller

RAZOR : FANTASY THRILLER - BECOMING A HERO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wilkie Martin | 250 pages | 22 Dec 2019 | Witcherley Book Company | 9781912348404 | English | none Razor : Fantasy Thriller - Becoming a Hero PDF Book PG min Drama, Family, Fantasy. First in the Black Dagger Brotherhood series. But soon victims are being found murdered by sorcery, with their hearts magically removed from their chests. The balance of tension and humour is perfect and the characters well rounded, even the more quirky ones Rocky is one of my favorites. An ancient Egyptian princess is awakened from her crypt beneath the desert, bringing with her malevolence grown over millennia, and terrors that defy human comprehension. What does this price mean? A buddy comedy is defined by at least two individuals who we follow through a series of humorous events. Winter Burdon Lane is part of a large group of criminals transporting a shipment of guns from Washington, D. Aislinn and Seth are a smart and compelling couple who must make tough choices throughout. Razor wants to die but he doesn't want to kill himself or harm any innocent in the process. Epic Western The idea of an epic western is to emphasize and incorporate many if not all of the western genre elements, but on a grand scale, and also use the backdrop of large scale real-life events to frame your story. Just as the deal is about to go down, bedlam erupts. If an alien force is the force of destruction, the film will be categorized as science fiction rather than a straight disaster movie.