The Future David of Psalm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm of David -David Expresses How He Will Live His Life Before God By

12/16/90 101:5 David now promises Gad bow he will deal with those in his kingdom. by the same standard God requires of him. -He will oppose the wicked. Psalms 101 — 108 101:8 Protect and defend the righteous. Psalm 101 101:7—8 Removal of all the evil. -Psalm of David Psalm 102 -David expresses how he will live his life before God -Psalm is a prayer of the afflicted, when he is by ~ of promises to God. overwhelmed and pours out his complaint before the -VS—l-4 The conduct of his private life as ~ believer. Lord. -VS—5-B The conduct of his public life as official —Personal lament with plead for the nation. king. -5th of penitential Psalms. 101:1 David knew much about God’s mercy -VS—1-11— The suffering of the psalmist. over -VS-12-22 The restoration of the nation. his life as well as the justice of God. -VS-23-28 The confidence of the psalmist. -Sparing his life from Saul and Achish. —2— 102:1—2 Urgency of help -Exposing his sin by Nathan. 102:4—5 Lack of food because of desire is 101:2 His walk in his home and family. gone 1) wisely in a perfect way and weight has been lost. (blameless). -Dealing with Issues and resolving . 102:6—9 Loneliness and sorrow. them. 2) Perfect heart - complete. Bold out. 102:10—11 God has chastened him for sin. 101:3 1 will not tempt myself by some 102:12 Turns to restoration of Zion. -

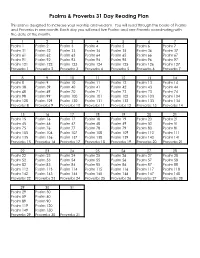

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

PSALMS 90-150 80 Books Four and Five

PSALMS 90-150 80 Books Four and Five BOOK FOUR (Psalms 90-106) Psalm 102: Prayer in time of distress Psalm 90: God and time In this fifth of seven Penitential Psalms, the psalmist experiences emotional and bodily pain and cries out This psalm, amongst other things, reflects on the to God. Because his worldview is that God is the relationship between God and time and the transience cause of all things, he assumes that God is the cause of human life. (See NAB for more.) of his current pain. (See NAB for more.) Psalm 91: God, my shelter Psalm 103: “Thank you, God of Mercy.” Often used for night prayer, this psalm images God This is a psalm of thanksgiving to the God who is full with big wings in whom we can find shelter in times of mercy for sinners. of danger. Much of the psalm hints at the story of the Exodus and wilderness wandering as it speaks of Psalm 104: Hymn of praise to God pathways, dangers, pestilence, tents, and serpents. As the psalmist sojourns along paths laden with dangers, This psalm is a hymn of praise to God the Creator the sole refuge is the Lord who “will cover you with whose power and wisdom are manifested in the his pinions, and under his wings you will find refuge” visible universe. (Ps 91:4). (See NAB for more.) Psalm 105: Another hymn of praise to God Psalm 92: Hymn of thanksgiving to God for his Like the preceding psalm, this didactic historical fidelity hymn praises God for fulfilling his promise to Israel. -

2 Samuel & 1 Chronicles with Associated Psalms

2 Samuel& 1 Chronicles w/Associated Psalms (Part 2 ) -Psalm 22 : The Psalm on the Cross . This anguished prayer of David was on the lips of Jesus at his crucifixion. Jesus’ prayed the psalms on the cross! Also, this is the most quoted psalm in the New Testament. Read this and then pray this the next time you experience anguish. -Psalm 23 : The Shepherd Psalm . Probably the best known psalm among Christians today. -Psalm 24 : The Christmas Processional Psalm . The Christmas Hymn, “Lift Up Your Heads, Yet Might Gates” is based on this psalm; also the 2000 chorus by Charlie Hall, “Give Us Clean Hands.” -Psalm 47 : God the Great King . Several hymns & choruses are based on this short psalmcelebrating God as the Great King over all. Think of “Psalms” as “Worship Hymns/Songs.” -Psalm 68 : Jesus Because of Hesed . Thematically similar to Psalms 24, 47, 132 on the triumphant rule of Israel’s God, with 9 stanzas as a processional liturgy/song: vv.1-3 (procession begins), 4-6 (benevolent God), 7-10 (God in the wilderness [bemidbar]), 11-14 (God in the Canaan conquest), 15-18 (the Lord ascends to Mt. Zion), 19-23 (God’s future victories), 24-27 (procession enters the sanctuary), 28-31 (God subdues enemies), 32-35 (concluding doxology) -Psalm 89 : Davidic Covenant (Part One) . Psalms 89 & 132 along with 2 Samuel 7 & 1 Chronicles 17 focus on God’s covenant with David. This psalm mourns a downfall in the kingdom, but clings to the covenant promises.This psalm also concludes “book 4” of the psalter. -

Royal Psalms Holy One to Supply by by Sister Michelle Mohr the Help of Grace

Oblates Newsletter for Oblates of the Sisters of St. Benedict of Ferdinand, Indiana July 2012 First of all, every time you begin a good work, you must pray to God most earnestly to bring it to perfection…. what “is not possible to us by nature, let us ask the Royal Psalms Holy One to supply by By Sister Michelle Mohr the help of grace. In his book, “Praying the Psalms,” Walter Bruggemann poses two considerations when we pray the psalms. The first —Rule of St. Benedict Prologue 4, 41 consideration is: What do we find in the psalms that is already there, and the second is: What do we bring to the psalms out of our own lives. The royal psalms, our topic today, are categorized according to their subject matter of kingship. Specifically the royal psalms A recipe for success deal with the spiritual role of kings in the worship of God. “Begin with a prayer, The Royal Psalms live and work in God’s Psalm 2, Psalm 18, Psalm 20, Psalm 21, Psalm 45, Psalm 72, Psalm 101, Psalm 110, Psalm 132, Psalm 144 presence, His” grace will strengthen you, and God Each of these psalms makes explicit references to the subject, the king. Although will be glorified in all it is possible that other psalms which do not mention the king directly, may have things.” been written for royalty, e. g. Psalm 22, they are not labeled royal psalms. In the book of Samuel we have the account of the people going to Samuel and demanding him to appoint a king to rule over them. -

Psalm 101: a Supplication for the Restoration of Society in the Late Post-Exilic Age

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 8 Original Research Psalm 101: A supplication for the restoration of society in the late post-exilic age Author: This article investigates the form and purpose of Psalm 101 from two perspectives: As a 1 Philippus J. Botha unique composition from the late Persian or early Hellenistic period, and in terms of its Affiliation: function within the context of Book IV of the Psalter. It is suggested that it was designed by 1Department of Ancient exponents of wisdom and Torah piety to serve as a ‘royal psalm’ at exactly this location in Languages and Cultures, the Psalter. It was meant to offer support to faithful Yahwists by criticising the apostate University of Pretoria, Judean aristocracy of its time of origin and serve as a prayer with which Yahweh could be South Africa beseeched to establish his righteous rule by judging evildoers and thus vindicating the Corresponding author: faithful. Phil Botha, [email protected] Dates: Introduction Received: 26 Feb. 2016 This article has a dual purpose: On the one hand, it offers an investigation of the form and function Accepted: 27 May 2016 Published: 19 Aug. 2016 of Psalm 101 as a text on its own, but it also proposes to describe the probable role that was assigned, by its editors, to this composition in Book IV of the Psalter. It will therefore initially be How to cite this article: investigated from an intratextual perspective and afterwards defined in terms of intertextual Botha, P.J., 2016, ‘Psalm 101: relations: correspondence with other, similar psalms and possible seminal sources that played a A supplication for the restoration of society in the role in its composition, but also its integration into Book IV of the Psalter. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

PSALM • 101 Translated by ALFRED VON ROHR SAUER 1

PSALM • 101 Translated by ALFRED VON ROHR SAUER 1. I will sing of mercy and justice and sing praises to Thee, O Lord. 2. I act discreetly and uprightly toward those who are under me and walk faithfully within my house. 3. I undertake no wicked thing, I hate the lawbreaker and will not let him abide with me. 4. A perverse heart must withdraw from me, I do not put up with the wicked person. 5. I destroy him who secretly maligns his neighbor, I am not fond of one who has a proud demeanor and is conceited in spirit. 6. My eyes look for the faithful in the land that they may dwell with me, and I delight in devout servants. 7. Deceitful people shall not dwell within my house, liars shall not prosper with me. 8. I will early destroy all the godless in the land, that I may cut off all evildoers from the city of the Lord. PREFACE THIS psalm is one of those which praise and thank God for the secular authorities, as is also done in Psalms 127 and 128 and in many others. Together with other psalms, this one has always been sung in the church by the clergy, who claimed that they alone were the church and the holy, favored people of God. But they did not realize or consider at all that in these psalms they were praising the very group with their mouth which they daily treated with utter contempt and practically trampled under their feet. Had they understood these psalms, I really think they would have omitted them and would never have sung them. -

Titles of Psalms 6,12

British Bible School – Online Classes: 14th September 2020 – 30th November 2020 THE PSALMS THE TITLES OF THE PSALMS 1. The superscriptions or titles found to many of the Psalms (116 have titles) are not thought to be part of the original text but do reflect an ancient and reliable description of the setting or occasion of writing. The Hebrew texts include them as part of the text of the Psalm. Some English versions, such as the New English Bible and the Good News Bible do not include them at all. Some of the terms used in some of the titles are obscure and their meaning cannot be ascertained for certain. Often the translators have simply transliterated the Hebrew word into English rather than try to offer an English equivalent. These titles reflect: i) The style or character of the Psalm. ii) The musical setting. iii) The occasion for use. iv) Authorship. v) The occasion of writing. 2. Titles that reflect the style or character of the Psalm i) MIZMOR – Translated as “Psalm” – occurs in 57 titles, e.g. Psalm 98. It is often followed by the name of the author, e.g. Psalm 101. It means ‘a song with instrumental accompaniment.’ ii) SHIR – Translated as “Song” – occurs in 30 titles, e.g. Psalm 108. It is a general term for a song. iii) MASKIL – occurs in 13 titles, e.g. Psalm 32; 42. The meaning of the term is uncertain. It may mean a teaching psalm or a meditation, or a psalm of understanding. iv) MIKHTAM – occurs in 6 titles, e.g. -

THE TRIBULATION PSALM with Verse References

THE TRIBULATION PSALM With Verse References DAY ONE 1) Psalm 8:1 O Lord, our Lord, How excellent is Your name in all the earth, Who have set Your glory above the heavens! 2) Psalm 97:9 For You, Lord, are most high above all the earth; You are exalted far above all gods. 3) Psalm 89:11 The heavens are Yours, the earth also is Yours; The world and all its fullness, You have founded them. 4) Psalm 102:25 Of old You laid the foundation of the earth, And the heavens are the work of Your hands. DAY TWO 5) Psalm 77:11 I will remember the works of the Lord; Surely I will remember Your wonders of old. 6) Psalm 93:2 Your throne is established from of old; You are from everlasting. 7) Psalm 75:1 We give thanks to You, O God, we give thanks! For Your wondrous works declare that Your name is near. 8) Psalm 48:10 According to Your name, O God, So is Your praise to the ends of the earth; Your right hand is full of righteousness. DAY THREE 9) Psalm 92:1-2 It is good to give thanks to the Lord, And to sing praises to Your name, O Most High; To declare Your lovingkindness in the morning, And Your faithfulness every night. 10) Psalm 143:8 Cause me to hear Your lovingkindness in the morning, For in You do I trust; Cause me to know the way in which I should walk, For I lift up my soul to You. -

Psalms 101-150

James Philip Bible Readings 54) Psalm 118 108)Psalm 128 1) Psalm 101 55) Psalm 119:1-16 109)Psalm 128 2) Psalm 101 56) Psalm 119:1-16 110)Psalm 129 3) Psalm 101 57) Psalm 119:1-16 111)Psalm 129 4) Psalm 102 58) Psalm 119:1-16 112)Psalm 129 5) Psalm 102 59) Psalm 119:17-40 113)Psalm 130 6) Psalm 102 60) Psalm 119:17-40 114)Psalm 130 7) Psalm 103 61) Psalm 119:17-40 115)Psalm 130 8) Psalm 103 62) Psalm 119:41-64 116)Psalm 131 9) Psalm 103 63) Psalm 119:41-64 117)Psalm 131 10) Psalm 104 64) Psalm 119:41-64 118)Psalm 131 11) Psalm 104 65) Psalm 119:65-96 119)Psalm 132 12) Psalm 104 66) Psalm 119:65-96 120)Psalm 132 13) Psalm 105 67) Psalm 119:65-96 121)Psalm 132 14) Psalm 105 68) Psalm 119:65-96 122)Psalm 133 15) Psalm 105 69) Psalm 119:97-120 123)Psalm 133 16) Psalm 106 70) Psalm 119:97-170 124)Psalm 133 17) Psalm 106 71) Psalm 119:97-120 125)Psalm 134 18) Psalm 106 72) Psalm 119:121-144 126)Psalm 134 19) Psalm 107 73) Psalm 119:121-144 127)Psalm 134 20) Psalm 107 74) Psalm 119:121-144 128)Psalm 135 21) Psalm 107 75) Psalm 119:145-160 129)Psalm 135 22) Psalm 108 76) Psalm 119:145-160 130)Psalm 135 23) Psalm 108 77) Psalm 119:145-160 131)Psalm 136 24) Psalm 108 78) Psalm 119:161-168 132)Psalm 136 25) Psalm 109 79) Psalm 119:161-166 133)Psalm 136 26) Psalm 109 80) Psalm 119:169-176 134)Psalm 137 27) Psalm 109 81) Psalm 119:169-176 135)Psalm 137 28) Psalm 109 82) Psalm 119:169-176 136)Psalm 137 29) Psalm 110 83) Psalm 120 137)Psalm 138 30) Psalm 110 84) Psalm 120 138)Psalm 138 31) Psalm 110 85) Psalm 120 139)Psalm 138 32) Psalm 111 86) Psalm -

Christ and His Church in the Book of Psalms

Christ and His Church in the Book of Psalms by Andrew Bonar Table of Contents Preface Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 119 Songs of Degrees Psalm 120 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 PREFACE FEW of the Books of Scripture are richer than the Book of Psalms, that "Hymn-book for all times," as it has been called.