The Catenary Degrees of Elements in Numerical Monoids Generated by Arithmetic Sequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formal Power Series - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Formal power series - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formal_power_series Formal power series From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In mathematics, formal power series are a generalization of polynomials as formal objects, where the number of terms is allowed to be infinite; this implies giving up the possibility to substitute arbitrary values for indeterminates. This perspective contrasts with that of power series, whose variables designate numerical values, and which series therefore only have a definite value if convergence can be established. Formal power series are often used merely to represent the whole collection of their coefficients. In combinatorics, they provide representations of numerical sequences and of multisets, and for instance allow giving concise expressions for recursively defined sequences regardless of whether the recursion can be explicitly solved; this is known as the method of generating functions. Contents 1 Introduction 2 The ring of formal power series 2.1 Definition of the formal power series ring 2.1.1 Ring structure 2.1.2 Topological structure 2.1.3 Alternative topologies 2.2 Universal property 3 Operations on formal power series 3.1 Multiplying series 3.2 Power series raised to powers 3.3 Inverting series 3.4 Dividing series 3.5 Extracting coefficients 3.6 Composition of series 3.6.1 Example 3.7 Composition inverse 3.8 Formal differentiation of series 4 Properties 4.1 Algebraic properties of the formal power series ring 4.2 Topological properties of the formal power series -

Sequence Rules

SEQUENCE RULES A connected series of five of the same colored chip either up or THE JACKS down, across or diagonally on the playing surface. There are 8 Jacks in the card deck. The 4 Jacks with TWO EYES are wild. To play a two-eyed Jack, place it on your discard pile and place NOTE: There are printed chips in the four corners of the game board. one of your marker chips on any open space on the game board. The All players must use them as though their color marker chip is in 4 jacks with ONE EYE are anti-wild. To play a one-eyed Jack, place the corner. When using a corner, only four of your marker chips are it on your discard pile and remove one marker chip from the game needed to complete a Sequence. More than one player may use the board belonging to your opponent. That completes your turn. You same corner as part of a Sequence. cannot place one of your marker chips on that same space during this turn. You cannot remove a marker chip that is already part of a OBJECT OF THE GAME: completed SEQUENCE. Once a SEQUENCE is achieved by a player For 2 players or 2 teams: One player or team must score TWO SE- or a team, it cannot be broken. You may play either one of the Jacks QUENCES before their opponents. whenever they work best for your strategy, during your turn. For 3 players or 3 teams: One player or team must score ONE SE- DEAD CARD QUENCE before their opponents. -

0.999… = 1 an Infinitesimal Explanation Bryan Dawson

0 1 2 0.9999999999999999 0.999… = 1 An Infinitesimal Explanation Bryan Dawson know the proofs, but I still don’t What exactly does that mean? Just as real num- believe it.” Those words were uttered bers have decimal expansions, with one digit for each to me by a very good undergraduate integer power of 10, so do hyperreal numbers. But the mathematics major regarding hyperreals contain “infinite integers,” so there are digits This fact is possibly the most-argued- representing not just (the 237th digit past “Iabout result of arithmetic, one that can evoke great the decimal point) and (the 12,598th digit), passion. But why? but also (the Yth digit past the decimal point), According to Robert Ely [2] (see also Tall and where is a negative infinite hyperreal integer. Vinner [4]), the answer for some students lies in their We have four 0s followed by a 1 in intuition about the infinitely small: While they may the fifth decimal place, and also where understand that the difference between and 1 is represents zeros, followed by a 1 in the Yth less than any positive real number, they still perceive a decimal place. (Since we’ll see later that not all infinite nonzero but infinitely small difference—an infinitesimal hyperreal integers are equal, a more precise, but also difference—between the two. And it’s not just uglier, notation would be students; most professional mathematicians have not or formally studied infinitesimals and their larger setting, the hyperreal numbers, and as a result sometimes Confused? Perhaps a little background information wonder . -

Arithmetic and Geometric Progressions

Arithmetic and geometric progressions mcTY-apgp-2009-1 This unit introduces sequences and series, and gives some simple examples of each. It also explores particular types of sequence known as arithmetic progressions (APs) and geometric progressions (GPs), and the corresponding series. In order to master the techniques explained here it is vital that you undertake plenty of practice exercises so that they become second nature. After reading this text, and/or viewing the video tutorial on this topic, you should be able to: • recognise the difference between a sequence and a series; • recognise an arithmetic progression; • find the n-th term of an arithmetic progression; • find the sum of an arithmetic series; • recognise a geometric progression; • find the n-th term of a geometric progression; • find the sum of a geometric series; • find the sum to infinity of a geometric series with common ratio r < 1. | | Contents 1. Sequences 2 2. Series 3 3. Arithmetic progressions 4 4. The sum of an arithmetic series 5 5. Geometric progressions 8 6. The sum of a geometric series 9 7. Convergence of geometric series 12 www.mathcentre.ac.uk 1 c mathcentre 2009 1. Sequences What is a sequence? It is a set of numbers which are written in some particular order. For example, take the numbers 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, .... Here, we seem to have a rule. We have a sequence of odd numbers. To put this another way, we start with the number 1, which is an odd number, and then each successive number is obtained by adding 2 to give the next odd number. -

3 Formal Power Series

MT5821 Advanced Combinatorics 3 Formal power series Generating functions are the most powerful tool available to combinatorial enu- merators. This week we are going to look at some of the things they can do. 3.1 Commutative rings with identity In studying formal power series, we need to specify what kind of coefficients we should allow. We will see that we need to be able to add, subtract and multiply coefficients; we need to have zero and one among our coefficients. Usually the integers, or the rational numbers, will work fine. But there are advantages to a more general approach. A favourite object of some group theorists, the so-called Nottingham group, is defined by power series over a finite field. A commutative ring with identity is an algebraic structure in which addition, subtraction, and multiplication are possible, and there are elements called 0 and 1, with the following familiar properties: • addition and multiplication are commutative and associative; • the distributive law holds, so we can expand brackets; • adding 0, or multiplying by 1, don’t change anything; • subtraction is the inverse of addition; • 0 6= 1. Examples incude the integers Z (this is in many ways the prototype); any field (for example, the rationals Q, real numbers R, complex numbers C, or integers modulo a prime p, Fp. Let R be a commutative ring with identity. An element u 2 R is a unit if there exists v 2 R such that uv = 1. The units form an abelian group under the operation of multiplication. Note that 0 is not a unit (why?). -

Formal Power Series License: CC BY-NC-SA

Formal Power Series License: CC BY-NC-SA Emma Franz April 28, 2015 1 Introduction The set S[[x]] of formal power series in x over a set S is the set of functions from the nonnegative integers to S. However, the way that we represent elements of S[[x]] will be as an infinite series, and operations in S[[x]] will be closely linked to the addition and multiplication of finite-degree polynomials. This paper will introduce a bit of the structure of sets of formal power series and then transfer over to a discussion of generating functions in combinatorics. The most familiar conceptualization of formal power series will come from taking coefficients of a power series from some sequence. Let fang = a0; a1; a2;::: be a sequence of numbers. Then 2 the formal power series associated with fang is the series A(s) = a0 + a1s + a2s + :::, where s is a formal variable. That is, we are not treating A as a function that can be evaluated for some s0. In general, A(s0) is not defined, but we will define A(0) to be a0. 2 Algebraic Structure Let R be a ring. We define R[[s]] to be the set of formal power series in s over R. Then R[[s]] is itself a ring, with the definitions of multiplication and addition following closely from how we define these operations for polynomials. 2 2 Let A(s) = a0 + a1s + a2s + ::: and B(s) = b0 + b1s + b1s + ::: be elements of R[[s]]. Then 2 the sum A(s) + B(s) is defined to be C(s) = c0 + c1s + c2s + :::, where ci = ai + bi for all i ≥ 0. -

A Mathematical Example: Factorial Example: Fibonnaci Sequence Fibonacci As a Recursive Function Fibonacci: # of Frames Vs. # Of

10/14/15 A Mathematical Example: Factorial Example: Fibonnaci Sequence • Non-recursive definition: • Sequence of numbers: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, ... a0 a1 a2 a3 a4 a5 a6 n! = n × n-1 × … × 2 × 1 § Get the next number by adding previous two = n (n-1 × … × 2 × 1) § What is a8? • Recursive definition: • Recursive definition: § a = a + a Recursive Case n! = n (n-1)! for n ≥ 0 Recursive case n n-1 n-2 § a0 = 1 Base Case 0! = 1 Base case § a1 = 1 (another) Base Case What happens if there is no base case? Why did we need two base cases this time? Fibonacci as a Recursive Function Fibonacci: # of Frames vs. # of Calls def fibonacci(n): • Function that calls itself • Fibonacci is very inefficient. """Returns: Fibonacci no. an § Each call is new frame § fib(n) has a stack that is always ≤ n Precondition: n ≥ 0 an int""" § Frames require memory § But fib(n) makes a lot of redundant calls if n <= 1: § ∞ calls = ∞ memo ry return 1 fib(5) fibonacci 3 Path to end = fib(4) fib(3) return (fibonacci(n-1)+ n 5 the call stack fibonacci(n-2)) fib(3) fib(2) fib(2) fib(1) fibonacci 1 fibonacci 1 fib(2) fib(1) fib(1) fib(0) fib(1) fib(0) n 4 n 3 fib(1) fib(0) How to Think About Recursive Functions Understanding the String Example 1. Have a precise function specification. def num_es(s): • Break problem into parts """Returns: # of 'e's in s""" 2. Base case(s): # s is empty number of e’s in s = § When the parameter values are as small as possible if s == '': Base case number of e’s in s[0] § When the answer is determined with little calculation. -

Curriculum Burst 86: Arithmetic Logs by Dr

Curriculum Burst 86: Arithmetic Logs By Dr. James Tanton, MAA Mathematician in Residence The sequence log12 162, log12 x , log12 y , log12 z , log12 1250 is an arithmetic progression. What is x ? QUICK STATS: MAA AMC GRADE LEVEL This question is appropriate for the upper high-school grade levels. MATHEMATICAL TOPICS Logarithms COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS F-BF.B5 (+) Understand the inverse relationship between exponents and logarithms and use this relationship to solve problems involving logarithms and exponents. MATHEMATICAL PRACTICE STANDARDS MP1 Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. MP2 Reason abstractly and quantitatively. MP3 Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. MP7 Look for and make use of structure. PROBLEM SOLVING STRATEGY ESSAY 7: PERSEVERENCE IS KEY SOURCE: This is question # 14 from the 2013 MAA AMC 12A Competition. 1 THE PROBLEM-SOLVING PROCESS: The best, and most appropriate, first step is always … 1 625 Okay, so d = log . 412 81 STEP 1: Read the question, have an emotional reaction to it, take a deep Oh! This is: breath, and then reread the question. 1 This question definitely looks scary! 625 4 d = log12 81 Let’s just keep calm and see if we can work our way through it, slowly. and 625=×= 25 25 54 and 81= 34 , so this is actually: There is a list of (horrid looking) numbers that are, we are 5 told, in “arithmetic progression.” This means they increase d = log12 . 3 by some constant amount from term-to-term. So the sequence is basically of the form: Alright. Feeling good! What was the question? A , Ad+ , Add++, Ad+ 3 , Ad+ 4 . -

A Set of Sequences in Number Theory

A SET OF SEQUENCES IN NUMBER THEORY by Florentin Smarandache University of New Mexico Gallup, NM 87301, USA Abstract: New sequences are introduced in number theory, and for each one a general question: how many primes each sequence has. Keywords: sequence, symmetry, consecutive, prime, representation of numbers. 1991 MSC: 11A67 Introduction. 74 new integer sequences are defined below, followed by references and some open questions. 1. Consecutive sequence: 1,12,123,1234,12345,123456,1234567,12345678,123456789, 12345678910,1234567891011,123456789101112, 12345678910111213,... How many primes are there among these numbers? In a general form, the Consecutive Sequence is considered in an arbitrary numeration base B. Reference: a) Student Conference, University of Craiova, Department of Mathematics, April 1979, "Some problems in number theory" by Florentin Smarandache. 2. Circular sequence: 1,12,21,123,231,312,1234,2341,3412,4123,12345,23451,34512,45123,51234, | | | | | | | | | --- --------- ----------------- --------------------------- 1 2 3 4 5 123456,234561,345612,456123,561234,612345,1234567,2345671,3456712,... | | | --------------------------------------- ---------------------- ... 6 7 How many primes are there among these numbers? 3. Symmetric sequence: 1,11,121,1221,12321,123321,1234321,12344321,123454321, 1234554321,12345654321,123456654321,1234567654321, 12345677654321,123456787654321,1234567887654321, 12345678987654321,123456789987654321,12345678910987654321, 1234567891010987654321,123456789101110987654321, 12345678910111110987654321,... How many primes are there among these numbers? In a general form, the Symmetric Sequence is considered in an arbitrary numeration base B. References: a) Arizona State University, Hayden Library, "The Florentin Smarandache papers" special collection, Tempe, AZ 85287- 1006, USA. b) Student Conference, University of Craiova, Department of Mathematics, April 1979, "Some problems in number theory" by Florentin Smarandache. 4. Deconstructive sequence: 1,23,456,7891,23456,789123,4567891,23456789,123456789,1234567891, .. -

The Strange Properties of the Infinite Power Tower Arxiv:1908.05559V1

The strange properties of the infinite power tower An \investigative math" approach for young students Luca Moroni∗ (August 2019) Nevertheless, the fact is that there is nothing as dreamy and poetic, nothing as radical, subversive, and psychedelic, as mathematics. Paul Lockhart { \A Mathematician's Lament" Abstract In this article we investigate some "unexpected" properties of the \Infinite Power Tower 1" function (or \Tetration with infinite height"): . .. xx y = f(x) = xx where the \tower" of exponentiations has an infinite height. Apart from following an initial personal curiosity, the material collected here is also intended as a potential guide for teachers of high-school/undergraduate students interested in planning an activity of \investigative mathematics in the classroom", where the knowledge is gained through the active, creative and cooperative use of diversified mathematical tools (and some ingenuity). The activity should possibly be carried on with a laboratorial style, with no preclusions on the paths chosen and undertaken by the students and with little or no information imparted from the teacher's desk. The teacher should then act just as a guide and a facilitator. The infinite power tower proves to be particularly well suited to this kind of learning activity, as the student will have to face a challenging function defined through a rather uncommon infinite recursive process. They'll then have to find the right strategies to get around the trickiness of this function and achieve some concrete results, without the help of pre-defined procedures. The mathematical requisites to follow this path are: functions, properties of exponentials and logarithms, sequences, limits and derivatives. -

1 Convergence Tests

Lecture 24Section 11.4 Absolute and Conditional Convergence; Alternating Series Jiwen He 1 Convergence Tests Basic Series that Converge or Diverge Basic Series that Converge X Geometric series: xk, if |x| < 1 X 1 p-series: , if p > 1 kp Basic Series that Diverge X Any series ak for which lim ak 6= 0 k→∞ X 1 p-series: , if p ≤ 1 kp Convergence Tests (1) Basic Test for Convergence P Keep in Mind that, if ak 9 0, then the series ak diverges; therefore there is no reason to apply any special convergence test. P k P k k Examples 1. x with |x| ≥ 1 (e.g, (−1) ) diverge since x 9 0. [1ex] k X k X 1 diverges since k → 1 6= 0. [1ex] 1 − diverges since k + 1 k+1 k 1 k −1 ak = 1 − k → e 6= 0. Convergence Tests (2) Comparison Tests Rational terms are most easily handled by basic comparison or limit comparison with p-series P 1/kp Basic Comparison Test 1 X 1 X 1 X k3 converges by comparison with converges 2k3 + 1 k3 k5 + 4k4 + 7 X 1 X 1 X 2 by comparison with converges by comparison with k2 k3 − k2 k3 X 1 X 1 X 1 diverges by comparison with diverges by 3k + 1 3(k + 1) ln(k + 6) X 1 comparison with k + 6 Limit Comparison Test X 1 X 1 X 3k2 + 2k + 1 converges by comparison with . diverges k3 − 1 √ k3 k3 + 1 X 3 X 5 k + 100 by comparison with √ √ converges by comparison with k 2k2 k − 9 k X 5 2k2 Convergence Tests (3) Root Test and Ratio Test The root test is used only if powers are involved. -

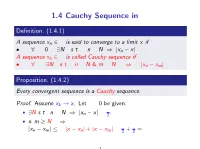

1.4 Cauchy Sequence in R

1.4 Cauchy Sequence in R De¯nition. (1.4.1) A sequence xn 2 R is said to converge to a limit x if ² 8² > 0; 9N s:t: n > N ) jxn ¡ xj < ²: A sequence xn 2 R is called Cauchy sequence if ² 8²; 9N s:t: n > N & m > N ) jxn ¡ xmj < ²: Proposition. (1.4.2) Every convergent sequence is a Cauchy sequence. Proof. Assume xk ! x. Let ² > 0 be given. ² ² 9N s:t: n > N ) jxn ¡ xj < 2 . ² n; m ¸ N ) ² ² jxn ¡ xmj · jx ¡ xnj + jx ¡ xmj < 2 + 2 = ²: 1 Theorem. (1.4.3; Bolzano-Weierstrass Property) Every bounded sequence in R has a subsequence that converges to some point in R. Proof. Suppose xn is a bounded sequence in R. 9M such that ¡M · xn · M; n = 1; 2; ¢ ¢ ¢ . Select xn0 = x1. ² Bisect I0 := [¡M; M] into [¡M; 0] and [0; M]. ² At least one of these (either [¡M; 0] or [0; M]) must contain xn for in¯nitely many indices n. ² Call it I1 and select n1 > n0 with xn1 2 I0. ² Continue in this way to get a subsequence xnk such that ² I0 ⊃ I1 ⊃ I2 ⊃ I3 ¢ ¢ ¢ ¡k ² Ik = [ak ; bk ] with jIk j = 2 M. ² Choose n0 < n1 < n2 < ¢ ¢ ¢ with xnk 2 Ik . 9 ² Since ak · ak+1 · M (monotone and bounded), ak ! x. ¡k ² Since xnk 2 Ik and jIk j = 2 M, we have ¡k¡1 jxnk ¡xj < jxnk ¡ak j+jak ¡ xj · 2 M+jak ¡ xj ! 0 as k ! 1: 2 Corollary. (1.4.5; Compactness) Every sequence in the closed interval [a; b] has a subsequence in R that converges to some point in R.