“ 'Sword-Point and Blade Will Reconcile Us First' ”1 the Vikings in the English Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MENTOR 81, January 1994

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #81 ARTICLES: 27 - 40,000 A.D. AND ALL THAT by Peter Brodie COLUMNISTS: 8 - "NEBULA" by Andrew Darlington 15 - RUSSIAN "FANTASTICA" Part 3 by Andrew Lubenski 31 - THE YANKEE PRIVATEER #18 by Buck Coulson 33 - IN DEPTH #8 by Bill Congreve DEPARTMENTS; 3 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 40 - THE R&R DEPT - Reader's letters 60 - CURRENT BOOK RELEASES by Ron Clarke FICTION: 4 - PANDORA'S BOX by Andrew Sullivan 13 - AIDE-MEMOIRE by Blair Hunt 23 - A NEW ORDER by Robert Frew Cover Illustration by Steve Carter. Internal Illos: Peggy Ranson p.12, 14, 22, 32, Brin Lantrey p.26 Jozept Szekeres p. 39 Kerrie Hanlon p. 1 Kurt Stone p. 40, 60 THE MENTOR 81, January 1994. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. Mail Address: PO Box K940, Haymarket, NSW 2000, Australia. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions, if over 5 pages, preferred to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD) in both ASCII and your word processor file or typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE anyway, for my comments. Contributions are not paid; however they receive a free copy of the issue their contribution is in, and any future issues containing comments on their contribution. -

Denis Micheal Rohan Ushering in the Apocalypse Contents

Denis Micheal Rohan Ushering in the Apocalypse Contents 1 Denis Michael Rohan 1 1.1 Motives .................................................. 1 1.2 Response ................................................. 2 1.2.1 Israeli Chief Rabbinate response ................................. 2 1.2.2 Arab/Muslim reactions ...................................... 2 1.3 See also .................................................. 3 1.4 References ................................................. 3 1.5 External links ............................................... 3 2 Mosque 4 2.1 Etymology ................................................. 5 2.2 History .................................................. 5 2.2.1 Diffusion and evolution ...................................... 6 2.2.2 Conversion of places of worship ................................. 9 2.3 Religious functions ............................................ 10 2.3.1 Prayers .............................................. 11 2.3.2 Ramadan events .......................................... 11 2.3.3 Charity .............................................. 12 2.4 Contemporary political roles ....................................... 12 2.4.1 Advocacy ............................................. 13 2.4.2 Social conflict ........................................... 14 2.4.3 Saudi influence .......................................... 14 2.5 Architecture ................................................ 15 2.5.1 Styles ............................................... 15 2.5.2 Minarets ............................................. -

Spring 2010 Catalogue:1 27/10/09 11:28 Page 1

Spring 10 Cat. Cover Final:1 21/10/09 11:13 Page 1 Yale University Press YALE spring 47 Bedford Square • London WC1B 3DP & summer 2010 yale spring & summer 2010 www.yalebooks.co.uk Spring 10 Cat. Inside Cover:1 21/10/09 11:11 Page 1 New Paperbacks see pages 23–26 & 71–78 YALE SALES REPRESENTATIVES & AGENTS Great Britain Austria, Germany, Italy Southern Africa Scotland and the North & Switzerland Book Promotions Peter Hodgkiss Uwe Lüdemann BMD Office Park 16 The Gardens Schleiermacherstr. 8 108 De Waal Road Whitley Bay NE25 8BG D-10961 Berlin Diep River 7800 Tel. 0191 281 7838 Germany South Africa Mobile ’phone 07803 012 461 Tel. (+49) 30 695 08189 Tel. (+27) 21 707 5700 e-mail: [email protected] Fax. (+49) 30 695 08190 e-mail: [email protected] North West England e-mail: [email protected] Nigeria Sally Sharp Central Europe Bounty Press Ltd. 53 Southway Ewa Ledóchowicz PO Box 23856 Eldwick PO Box 8 Mapo Post Office Bingley 05-520 Konstancin-Jeziorna Ibadan £10.99* £12.99* £10.99* £12.99* West Yorkshire BD16 3DT Poland Nigeria Reason, Faith, The Euro Fixing Global Finance The Crisis of Islamic Tel. 01274 511 536 Tel. (+48) 22 754 17 64 Tel. (+234) 22 311359/315604 and Revolution David Marsh Martin Wolf Civilization Mobile ’phone 07803 008 218 Fax. (+48) 22 756 45 72 Terry Eagleton Ali A. Allawi Africa, except Southern Africa e-mail: [email protected] Mobile ’phone (+48) 606 488 122 & Nigeria Wales, South West England e-mail: [email protected] Kelvin van Hasselt and The Midlands Spain & Portugal Willow House inc. -

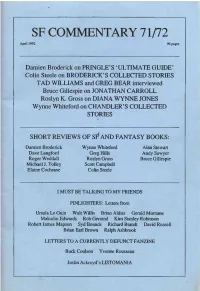

SF Commentary 71-72

SF COMMENTARY 71/72 April 1992 96 pages Damien Broderick on PRINGLE’S ‘ULTIMATE GUIDE’ Colin Steele on BRODERICK’S COLLECTED STORIES TAD WILLIAMS and GREG BEAR interviewed Bruce Gillespie on JONATHAN CARROLL Roslyn K. Gross on DIANA WYNNE JONES Wynne Whiteford on CHANDLER’S COLLECTED STORIES SHORT REVIEWS OF SI# AND FANTASY BOOKS: Damien Broderick Wynne Whiteford Alan Stewart Dave Langford Greg Hills Andy Sawyer Roger Weddall Roslyn Gross Bruce Gillespie Michael J. Tolley Scott Campbell Elaine Cochrane Colin Steele I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS PINLIGHTERS: Letters from Ursula Le Guin Walt Willis Brian Aldiss Gerald Mumane Malcolm Edwards Rob Gerrand Kim Stanley Robinson Robert James Mapson Syd Bounds Richard Brandt David Russell Brian Earl Brown Ralph Ashbrook LETTERS TO A CURRENTLY DEFUNCT FANZINE Buck Coulson Yvonne Rousseau Justin Ackroyd’s LISTOMANIA SF COMMENTARY 71/72 April 1992 96 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 71/72, May 1992, is edited by published by Bruce Gillespie, GPO Box 5195AA, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia. Phone: (03) 419 4797. Printed by Copyplace, Melbourne. Editorial assistant and banker: Elaine Cochrane. Available for subscriptions ($25 within Australia, equivalent of US$25 (airmail) overseas), written or art contributions, traded publications, or donations. ART Most of the art is out of copyright, available from various Dover Publications. Back cover and Page 15 illustrations: C. M. Hull. Book covers and photo of Jonathan Carroll (p. 28): thanks to Locus magazine. TECHNICAL STUFF This is my first big publication in Ventura 3.0. Thanks to Elaine Cochrane, Martin Hooper, Charles Taylor, Tony Stuart and several others who endured my endless learning process. -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

F Faòer ffoo^r of Modem Verse, The, an anthology FABIUS (Quintus Fabius Maximus) (d. 203 BC), nick published in 1936, edited by M. *Roberts, which did named Cunctator (the man who delays taking action), much to influence taste and establish the reputations of was appointed dictator after Hannibal's crushing a rising generation of poets, including *Auden, *Mac- victory at Trasimene (217 BC). He carried on a defensive Neice, *Empson, *Graves, Dylan Thomas. In his campaign, avoiding direct engagements and harassing introduction, Roberts traces the influences of *Clough, the enemy. Hence the expression 'Fabian tactics' and G. M. *Hopkins (himself well represented), the French the name of the *Fabian Society (1884), dedicated to ^symbolists, etc. on modern poetry, defines the 'Euro the gradual introduction of socialism. pean' sensibility of such writers as T. S. *Eliot, *Pound, and * Yeats, and offers a persuasive apologia for various fable, a term most commonly used in the sense of a aspects of *Modernism which the reading public had short story devised to convey some useful moral resisted, identifying them as an apparent obscurity lesson, but often carrying with it associations of the compounded of condensed metaphor, allusion, intri marvellous or the mythical, and frequently employing cacy and difficulty of ideas, and verbal play. The poet, animals as characters. * Aesop's fables and the *'Rey- he declared, 'must charge each word to its maximum nard the Fox' series were well known and imitated in poetic value': 'primarily poetry is an exploration of the Britain by *Chaucer, *Henryson, and others, and *La possibilities of language.' Fontaine, the greatest of modern fable writers, was imitated by *Gay. -

Finalmente Pubblicati Gli Atti Del Convegno Di Birmingham!

Finalmente pubblicati gli Atti del Convegno di Birmingham! The Ring Goes Ever On: Proceedings of the Tolkien 2005 Conference celebrating 50 Years of The Lord of the Rings, 2 vv., edited by Sarah Wells, was published by The Tolkien Society at Coventry at the end of September 2008. Gli Atti sono in due volume inseparabili per un totale di 837 pagine in formato A4. In undici sezioni vi sono 98 saggi di 95 differenti autori. Le voci dell’indice analitico sono 1.800 Per ordinarli: sul sito web della Tolkien Society con carta di credito Contenuti Section One: Tolkien's Life The Ace Copyright Affair Nancy Martsch "As under a green sea": visions of war in the Dead Marshes John Garth Invented, Borrowed, and Mixed Myths in the "kinds of books we want to read" Sharin Schroeder The Complexity of Tolkien's Attitude Towards the Second World War Franco Manni and Simone Bonechi Romantic Conservatives: The Inklings in Their Political Context Charles A. Coulombe We Had Nothing to Say to One Another — J.R.R. Tolkien and Charles Williams, Another Look Eric Rauscher On Tolkien, and Williams, and Tolkien on Williams Richard Sturch. Section Two: Tolkien's Literary Achievement Containment and Progression in J.R.R. Tolkien's World Marjorie Burns Approaching Reality in The Lord of the Rings Andrea Ulrich Tolkien as a Benchmark of Comparative Literature — Middle-earth in Our World Giovanni Agnoloni From Beowulf to Post-modernism: Interdisciplinary Team-Teaching of J.R.R.Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings Robin Anne Reid and Judy Ann Ford The Great Questions Ella van Wyk Unlocking Supplementary Events in the Dreams, Visions, and Prophesies of J.R.R. -

The Academical the MAGAZINE for ACADEMICALS ACROSS the GLOBE | 2019

The Academical THE MAGAZINE FOR ACADEMICALS ACROSS THE GLOBE | 2019 in this issue CORDELIA FINE (EA 1990–92) also in this issue EDWINA BROWN (EA 1966–67) TO24 CAMPAIGN BLAIR KINGHORN (EA 20 02–15) EA WOMEN IN SCIENCE ROBERT A DICKSON (EA 1948–60) MEMORIES OF 1960s EA RUGBY CATHERINE KELLETT (EA 1986–88) ACCIES’ RECENT PUBLICATIONS SAMUEL ANDERSON (EA 1968–69) UPDATE ON RAEBURN PLACE GEORGE BALLENTYNE (EA 1981–90) CONNECT WITH ACADEMICALS ACROSS THE GLOBE We invite you to join the official networking platform for Alumni of the Edinburgh Academy. RE-CONNECT GIVE BACK EXPAND GET AHEAD Find and reminisce with Introduce, employ and Leverage your professional Advance your career classmates, see what they be a mentor to our network to get introduced through inside connections have been up to and stay graduating students. to people you should know. working in top companies in touch. and access to exclusive opportunities. CONNECT NOW: WWW.LINKEDIN.COM/IN/THEACADEMICALCLUB/ Contact us Changed address recently? [email protected] Please let us know if your address has changed. Contact the Development and Alumni Relations Office on+44 (0)131 624 4958 or at [email protected] 0131 624 4958 Sponsored & published by the Edinburgh Academy @AcademicalClub 42 Henderson Row, Edinburgh EH3 5BL No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior written consent of the publishers. The views expressed in its features are those of the contributors /theacademicalclub and do not necessarily represent those of the Edinburgh Academy. Editor’s Welcome Contents Dear Accies The Academical Club Report Welcome to the latest edition of The Academical. -

THE MENTOR 80, October 1993

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #80 2 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 3 - THE JAM JAR by Brent Lillie 5 - THE YANKEE PRIVATEER #17 by Buck Coulson 6 - FROM HUDDERSFIELD TO THE STARS by Steve Sneyd 8 - A SHORT HISTORY OF RUSSIAN "FANTASTIKA" by Andrew Lubenski 17 - A PERSONAL REFERENCE LIBRARY ON A BUDGET by James Verran 18 - JET-ACE LOGAN: The Next Generation by Andrew Darlington 25 - IN DEPTH by Bill Congreve 29 - THE R & R DEPT - Reader's letters 42 - REVIEWS Cover by Antoinette Rydyr Internal Illos: Peggy Ranson p. 4, 28 Kurt Stone p. 29, 42 THE MENTOR 80, October 1993. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. NEW POSTAL ADDRESS: THE MENTOR, PO BOX 940K, HAYMARKET, NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions preferred if over 5 pages to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD). Or typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE! so I can make comments on THE MENTOR 80 page 1 submitted works. Contributions are not paid; however they receive a free copy of the issue their contribution is in, and any future issue containing comments on their contribution. -

WELCOME to the PROMS! SIR ANDREW DAVIS and Sir Henry Wood Invite You to the World’S Greatest Music Festival PLUS! FULL PROMS LISTINGS See P28

CDS, DVDSREVIEWS & BOOKS115 THE WORLD’S BEST-SELLING CLASSICAL MUSIC MAGAZINE FULL BBC RADIO 3 & CLASSICAL MUSIC TV LISTINGS! See p100 see p65 THE SUMMER STARTS HERE… WELCOME TO THE PROMS! SIR ANDREW DAVIS and Sir Henry Wood invite you to the world’s greatest music festival PLUS! FULL PROMS LISTINGS See p28 INSIDE YOUR SPECIAL ISSUE including Behind the scenes What does it take to bring the Albert Hall to your living room? Harrison Birtwistle We talk to the composer who caused panic at the Proms Beethoven Why the greatest symphonist vk.com/englishlibrary GREATfound writing WORKS opera EXPLORED! so difficult PLUS HUNDREDS OF OTHER TITLES AVAILABLE AT GREAT PRICES FROM PARTICIPATING RETAILERS PRICES FROM PARTICIPATING GREAT AT PLUS HUNDREDS OF OTHER TITLES AVAILABLE BEST-SELLING BEST-SELLING BLU-RAY & DVD FROM WARNER CLASSICS & ERATO DVD: 2564632323 Blu-Ray: 2564654365 / DVD: 2564656309 Blu-Ray: 2564660478 / DVD: 2564660468 Marketed and distributed by Warner Classics UK. A division of Warner Music UKLtd. ClassicsUK. Adivision ofWarner Marketed anddistributed by Warner www.warnerclassics.com DVD: 5991569 Blu-Ray: 2564646145 / DVD: 0630154812 Blu-Ray: 2564656333 / DVD: 2564688804 DVD: 5190029 DVD: 2564632035 Blu-Ray: 4040649 / DVD: 4040639 vk.com/englishlibrary JULY 2014 THE MONTH IN MUSIC THE MONTH IN MUSIC The recordings, concerts, broadcasts and websites exciting us this July ON AIR Let the Proms begin! The BBC Proms are back! The 120th season begins with a distinctly British flavour as Sir Andrew Davis raises the baton for Elgar’s mighty oratorio, The Kingdom, on the First Night. Tune in to hear the combined forces of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, plus star soloists, in the live Radio 3 broadcast, or watch it in glorious colour later on BBC Two. -

Lunicon Programme Book

WELCOME Welcome to Lunicon!Ifthis is your first convention, then we hopethat you will be madeto feel welcome andthat youwill start to understand the idea of ‘fandom’, whichis the group of people around you whoregularly attend conventions(fans) and what they do(fanac — fan activity). As a student convention wearetrying to be as friendly as possible to the newcomers, If you are a fan, then please try to make others feel welcome. And everybody, relax! THE BAR The bar will be open the following times: Ea 6pm — Ilpm Sat. : llam — ilpm Sun. : llam— 3pm, 7pm — 10.30pm You will be warned before the bar shuts andthere will be plenty of cans and bottled drinks available for sale. We regret that there is noreal ale, but the permanent barman hasrecentlyleft, leaving the hall slightly confused. Orange juice should be available cheap. ROOMS Roomsare available at £19 pppn and doesnot include breakfast. Sorry, no doubles. Please return room keys by 10am of your day of departure. A quiet/noisy area system is in operation. BREAKFAST Breakfast is 8:30 — 9:30am sharp and costs £2.50 CREDITS Text by Tara Dowling-Hussey, Jon Foster, Barry Traish. Layout by Barry Traish. Thanksto all the Guests and programmeitem participents and to you for turning up. avee ROGER ZELAZNY COLIN GREENLAND Roger was born in 1937, got interested in fantasy with the Doctor Doolittle Colin Greenlandis most celebrated for his intriguing space opera, 7ake stories as a child, discovered sciencefiction four years later and read everything Back Plenty which has deservedly won both the BSFA and Arthur C. -

St Edmund Hall 2017–2018 St Edmund Hall

MagazineST EDMUND HALL 2017–2018 ST EDMUND HALL EDITOR: Dr Brian Gasser (1975) With many thanks to all the contributors to this year’s edition: especially to Claire Hooper, Communications Manager, and Sarah Wright for their great help with the production. [email protected] St Edmund Hall Oxford OX1 4AR 01865 279000 www.seh.ox.ac.uk [email protected] @StEdmundHall StEdmundHall @StEdmundHall FRONT COVER: MAGAZINE Graduation Day 21 July 2018 (photo by Stuart Bebb) FRESHERS’ PICTURES: Photographs by Gillman & Soame All the photographs in this Magazine are from Hall records unless otherwise stated. VOL. XVIII NO. 9 ST EDMUND HALL MAGAZINE Centre for the Creative Brain ....................................................................................97 OCTOBER 2018 Links with China .........................................................................................................98 Aula Narrat ...................................................................................................................99 Benefactors’ Square ..................................................................................................100 SECTION 1: THE COLLEGE LIST: 2017–2018 ......................................................1 Well Done: New Gilding for the Hall’s Historic Well ......................................... 101 Receptions & Reunions at the Hall ........................................................................ 101 SECTION 2: REPORTS ON THE YEAR ...............................................................