Functional Neurological Disorder: a Practical Guide to an Elusive Dx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation and Care of a Family with Huntington Disease in a Resource

Charles et al. Journal of Clinical Movement Disorders (2017) 4:4 DOI 10.1186/s40734-017-0050-6 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Presentation and care of a family with Huntington disease in a resource-limited community Jarmal Charles1†, Lindyann Lessey1†, Jennifer Rooney1†, Ingmar Prokop1, Katherine Yearwood1, Hazel Da Breo1, Patrick Rooney1, Ruth H. Walker2,3 and Andrew K. Sobering1* Abstract Background: In high-income countries patients with Huntington disease (HD) typically present to healthcare providers after developing involuntary movements, or for pre-symptomatic genetic testing if at familial risk. A positive family history is a major guide when considering the decision to perform genetic testing for HD, both in affected and unaffected patients. Management of HD is focused upon control of symptoms, whether motor, cognitive, or psychiatric. There is no clear evidence to date of any disease-modifying agents. Referral of families and caregivers for psychological and social support, whether to HD-focused centers, or through virtual communities, is viewed as an important consequence of diagnosis. The experience of healthcare for such progressive neurodegenerative diseases in low- and middle-income nations is in stark contrast with the standard of care in high-income countries. Methods: An extended family with many members affected with an autosomal dominantly inherited movement disorder came to medical attention when one family member presented following a fall. Apart from one family member who was taking a benzodiazepine for involuntary movements, no other affected family members had sought medical attention. Members of this family live on several resource-limited Caribbean islands. Care of the chronically ill is often the responsibility of the family, and access to specialty care is difficult to obtain, or is unavailable. -

Parkinson's Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know

Parkinson’s Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know Edited by Gale Kittle, RN, MPH Parkinson’s Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know Table of Contents Chapter 1: Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic Understanding .....................................3 Chapter 2: Medical and Surgical Treatment Options ..........................................11 Chapter 3: Staying Well with Parkinson’s Disease ...............................................16 Chapter 4: Taking Charge of Your Health Care .....................................................22 Chapter 5: Accepting and Adapting to PD ..............................................................27 Chapter 6: Special Concerns of Persons with Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease ........................................................31 Glossary ........................................................................................................................36 About the National Parkinson Foundation ................................................................................38 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... 40 Parkinson’s Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know Chapter 1 Parkinson’s Disease’s: A Basic Understanding Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex disorder of the brain. Because it is a disease that affects the brain, it is classified as a neurological disorder – neurological means “related to the nerves” – and the doctors who specialize in diseases that affect the -

Prevalence and Classification of Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study Part 1

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Prevalence and Classification of Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study Part 1 Oscar L. Lopez, MD; William J. Jagust; Steven T. DeKosky, MD; James T. Becker, PhD; Annette Fitzpatrick, PhD; Corinne Dulberg, PhD; John Breitner, MD; Constantine Lyketsos, MD; Beverly Jones, MD; Claudia Kawas, MD; Michelle Carlson, PhD; Lewis H. Kuller, MD Objective: To examine the prevalence of mild cogni- was classified as either MCI amnestic-type or MCI mul- tive impairment (MCI) and its diagnostic classification tiple cognitive deficits–type. in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Cognition Study. Results: The overall prevalence of MCI was 19% (465 of 2470 participants); prevalence increased with age from Design: The CHS Cognition Study is an ancillary study 19% in participants younger than 75 years to 29% in those of the CHS that was conducted to determine the pres- older than 85 years. The overall prevalence of MCI at the ence of MCI and dementia in the CHS cohort. Pittsburgh center was 22% (130 of 599 participants); prevalence of the MCI amnesic-type was 6% and of the Setting: Multicenter population study. MCI multiple cognitive deficits–type was 16%. Patients: We examined 3608 participants in the CHS Conclusions: Twenty-two percent of the participants who had undergone detailed neurological, neuropsycho- aged 75 years or older had MCI. Mild cognitive impair- logical, neuroradiological, and psychiatric testing to iden- ment is a heterogenous syndrome, where the MCI am- tify dementia and MCI. nestic-type is less frequent than the MCI multiple cog- nitive deficits–type. Most of the participants with MCI Main Outcome Measures: The prevalence of MCI was had comorbid conditions that may affect their cognitive determined for the whole cohort, and specific subtypes functions. -

Capgras Syndrome Subbarayan Dhivagar1, Jasmine Farhana2

REVIEW ARTICLE Capgras Syndrome Subbarayan Dhivagar1, Jasmine Farhana2 ABSTRACT Capgras syndrome is a neuropsychiatric disorder, and it is also known as impostor syndrome. People who experience this syndrome will have an irrational belief that someone they know or recognize has been replaced by an impostor. The Capgras syndrome can affect anyone, but it is more common in females and rare cases in children. There is no prescribed treatment plan for people who are affected with Capgras syndrome, but there is a supportive psychotherapeutic measure to overcome this delusional disorder. Keywords: Impostor delusion, Misidentification syndrome, Prosopagnosia. Pondicherry Journal of Nursing (2020): 10.5005/jp-journals-10084-12151 INTRODUCTION 1,2Department of Mental Health Nursing, Kasturba Gandhi Nursing Capgras syndrome is a type of delusional disorder in which a person College, Sri Balaji Vidyapeeth, Puducherry, India holds a delusion that a friend, parents, spouse, or other close Corresponding Author: Subbarayan Dhivagar , Department of relatives or pet animals has been replaced by an identical impostor. Mental Health Nursing, Kasturba Gandhi Nursing College, Sri Balaji It is otherwise called as Capgras delusion or impostor delusion. Vidyapeeth, Puducherry, India, Phone: +91 8754733698, e-mail: It may be seen along with other psychiatric disorders such as [email protected] schizophrenia, schizotypal, and neuro-related disorders. How to cite this article: Dhivagar S, Farhana J. Capgras Syndrome. Pon J Nurs 2020;13(2):46–48. HISTORICAL VIEW Source of support: Nil It is named after Jean Marie Joseph Capgras (1873–1950). He was a Conflict of interest: None French psychiatrist, who was best known for the Capgras delusion; it was described in 1923 in a study published by him. -

Functional Neurological Disorder

Functional Neurological Disorder (FND) Learning guide Written by: Phuong Nhan, Registered Nurse Vincent Cheah, Registered Nurse Reviewed by: Dr Alexander Lehn, Neurologist Dr Megan Broughton, Neuropsychologist Dr Rian Dob, Neuropsychologist Dharsha Navaratnam, Physiotherapist Our Mission In the spirit of the Sisters of Mercy, the Mater Hospital offers compassionate service to the sick and needy, promotes an holistic approach to healthcare in response to changing community needs and fosters high standards in health-related education and research. Following the example of Christ the healer, we commit ourselves to offering these services to all without discrimination. Our Values Mercy: The spirit of responding to one another Dignity: The spirit of humanity, respecting the worth of each person Care: The spirit of compassion Commitment: The spirit of integrity Quality: The spirit of professionalism 2 Contents Functional Neurological Disorder learning guide 4 Aim ........................................................................................................ 4 Guide outline .......................................................................................... 4 Introduction to FND 5 What is FND? .......................................................................................... 5 A brief history of FND .............................................................................. 5 Glossary of key terminologies 6 Who is at risk? 7 Symptoms of FND 8 Functional motor disorders .................................................................... -

Functional Cognitive Disorder: Dementia's Blind Spot

doi:10.1093/brain/awaa224 BRAIN 2020: Page 1 of 9 | 1 UPDATE Functional cognitive disorder: dementia’s blind Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/brain/advance-article/doi/10.1093/brain/awaa224/5892366 by guest on 20 October 2020 spot Harriet A. Ball,1 Laura McWhirter,2 Clive Ballard,3 Rohan Bhome,4 Daniel J. Blackburn,5 Mark J. Edwards,6 Stephen M. Fleming,7 Nick C. Fox,8 Robert Howard,4 Jonathan Huntley,4 Jeremy D. Isaacs,6,9 Andrew J. Larner,10 Timothy R. Nicholson,11 Catherine M. Pennington,2 Norman Poole,9 Gary Price,12 Jason P.Price,13 Markus Reuber,5 Craig Ritchie,2 Martin N. Rossor,8 Jonathan M. Schott,8 Tiago Teodoro,6,14 Annalena Venneri,5 Jon Stone2 and Alan J. Carson2 An increasing proportion of cognitive difficulties are recognized to have a functional cause, the chief clinical indicator of which is intern- al inconsistency. When these symptoms are impairing or distressing, and not better explained by other disorders, this can be conceptual- ized as a cognitive variant of functional neurological disorder, termed functional cognitive disorder (FCD). FCD is likely very common in clinical practice but may be under-diagnosed. Clinicians in many settings make liberal use of the descriptive term mild cognitive im- pairment (MCI) for those with cognitive difficulties not impairing enough to qualify as dementia. However, MCI is an aetiology-neutral description, which therefore includes patients with a wide range of underlying causes. Consequently, a proportion of MCI cases are due to non-neurodegenerative processes, including FCD. Indeed, significant numbers of patients diagnosed with MCI do not ‘convert’ to de- mentia. -

What Is Schizophrenia?

What Is Schizophrenia? What is schizophrenia? Although currently classified as a mental illness, schizophrenia is now scientifically accepted as a neurobiological brain illness. A Syndrome Schizophrenia, a neurobiological brain syndrome, includes possibly hundreds of distinct brain diseases. These diseases are sometimes referred to as “schizophrenia spectrum disorders.” Symptoms vary greatly among different people. The most widely accepted theory of schizophrenia is that it is a neurodevelopmental disorder, which means that normal brain development during fetal life is disrupted due to various genetic factors and/or environmental factors. Schizophrenia usually starts in adolescence or early twenties in males and in the late 20s and early 30s in some females. A Brain Disorder While schizophrenia is clearly a neurological disorder like stroke, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease and others – schizophrenia is still classified as a mental illness. It should be emphasized that one of the most important jobs of the brain is to generate the mind, and thus all mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, major depression or panic disorder are actually caused by abnormalities in brain structure and function. As Thomas Insel, MD – former Director of the National Institute of Mental Health – said, “Mental disorders are biological disorders involving brain circuits.” There are hundreds of “biotypes” within the schizophrenia syndrome, but they all share a similar phenotype of psychosis, cognitive deficits and negative symptoms. Clinical Features of Schizophrenia Schizophrenia affects about 1% of the world’s population, (60 million people, around the world). Symptoms of schizophrenia may include hallucinations (seeing, hearing or smelling things that are not really there) and delusions (persistent false beliefs, such as that someone plans to harm them or that the affected individual is a person is a prophet, or member of the CIA). -

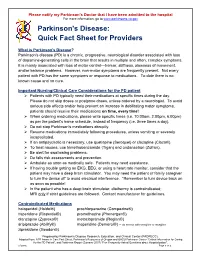

Quick Fact Sheet for Providers

Please notify my Parkinson’s Doctor that I have been admitted to the hospital For more information, go to www.parkinsons.va.gov Parkinson's Disease: Quick Fact Sheet for Providers What is Parkinson's Disease? Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive, neurological disorder associated with loss of dopamine-generating cells in the brain that results in multiple and often, complex symptoms. It is mainly associated with loss of motor control—tremor, stiffness, slowness of movement, and/or balance problems. However, non-motor symptoms are frequently present. Not every patient with PD has the same symptoms or response to medications. To date there is no known cause and no cure. Important Nursing/Clinical Care Considerations for the PD patient Patients with PD typically need their medications at specific times during the day. Please do not skip doses or postpone doses, unless ordered by a neurologist. To avoid serious side effects and/or help prevent an increase in debilitating motor symptoms, patients should receive their medications on time, every time! When ordering medications, please write specific times (i.e. 10:00am, 2:00pm, 6:00pm) as per the patient's home schedule, instead of frequency (i.e. three times a day). Do not stop Parkinson's medications abruptly. Resume medications immediately following procedures, unless vomiting or severely incapacitated. If an antipsychotic is necessary, use quetiapine (Seroquel) or clozapine (Clozaril). To treat nausea, use trimethobenzamide (Tigan) and ondansetron (Zofran). Be alert for swallowing problems. Do falls risk assessments and prevention. Ambulate as soon as medically safe. Patients may need assistance. -

Physical and Occupational Therapy

Physical and Occupational Therapy Huntington’s Disease Family Guide Series Physical and Occupational Therapy Family Guide Series Reviewed by: Suzanne Imbriglio, PT Edited by Karen Tarapata Deb Lovecky HDSA Printing of this publication was made possible through an educational grant provided by The Bess Spiva Timmons Foundation Disclaimer Statements and opinions in this book are not necessarily those of the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, nor does HDSA promote, endorse, or recommend any treatment mentioned herein. The reader should consult a physician or other appropriate healthcare professional concerning any advice, treatment or therapy set forth in this book. © 2010, Huntington’s Disease Society of America All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any way without the expressed written permission of HDSA. Contents Introduction Movement Disorders in HD 4 Cognitive Disorders 8 The Movement Disorder and Nutrition 9 Physical Therapy in Early Stage HD Pre-Program Evaluation 11 General Physical Conditioning for Early Stage HD 14 Cognitive Functioning and Physical Therapy 16 Physical Therapy in Mid-Stage HD Assessment in Mid-Stage HD 17 Functional Strategies for Balance and Seating 19 Physical Therapy in Later Stage HD Restraints and Specialized Seating 23 Accommodating the Cognitive Disorder in Later Stage HD 24 Occupational Therapy in Early Stage HD Addressing the Cognitive Disability 26 Safety in the Home 28 Occupational Therapy in Mid-Stage HD Problems and Strategies 29 Occupational Therapy in Later Stage HD Contractures 33 Hope for the Future 34 Introduction Understanding Huntington’s Disease Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a hereditary neurological disorder that leads to severe physical and mental disabilities. -

POS-Psychoorganic Syndrome

Endocrinology & Metabolic Syndrome Opinion POS-Psychoorganic Syndrome Himabindhu Gude* Department of Biotechnology, Osmania University College of Science, Tarnaka, Hyderabad, Telangana, India caused changes in the brain by organic. The particular Psychoorganic syndrome is also known as organic component of the solvents causes neurological disorder and is psychosyndrome. It is a progressive disease comparable to difficult to isolate due to expose of many compositions, grades, dementia. It consists of psychopathological symptoms which are and purity of solvents. At the initial stage, asthenia is prevalent caused by brain disorders which involves in reduction of and the progress of the disorder is slow. Acute onset is memory and intellect. Psychoorganic syndrome occurs in diagnosed when a great amount of psychological symptoms atrophy of brain, and mostly during senile and presenile age surface. The last stage of this disorder is made up of numerous (e.g. senile dementia, presenile dementia, Alzheimer's disease). disorders, like dementia, Korsakov's syndrome, and includes There are several causes, like CNS damages to traumatic brain severe personality change such as depression, anxiety, memory injury, cerebrovascular diseases, intoxication, exposure to loss, and drastic change in intellect. Level of kindness, organic solvents such as toluene, tumors, chronic metabolic happiness, and insight are greatly affected in the final stage. disorders, encephalitis,and abscesses of the brain, also be found in case of diseases accompanied by convulsive seizures. Although the exact mechanisms that solvents have on the Psychoorganic syndrome occurs at any age but is most nervous system are not fully understood, the metabolisms of the pronounced in elderly presenile and senile age. -

Specific Neurological Phenotypes in Autism Spectrum Disorders Are Associated with Sex Representation RESEARCH ARTICLE

RESEARCH ARTICLE Specific Neurological Phenotypes in Autism Spectrum Disorders Are Associated with Sex Representation Esther Ben-Itzchak, Shay Ben-Shachar, and Ditza A. Zachor Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heritable disorder occurring predominantly in males. The aim of this study was to compare sex differences in the prevalence of specific neurological phenotypes commonly described in ASD. The study included 663 participants, aged 18 months to 15 years, diagnosed with ASD. Neurological and behavioral assessments were performed using standardized tests, and obtaining medical, developmental, and familial histories from the parents. Phenotypes under investigation were macro- and microcephaly, developmental regression, minor neurological and musculoskeletal deficits (MNMD), and seizures. Male : female ratio in the ASD group was 6.7:1. No sex differences in autism severity, cognitive ability, and adaptive functioning were noted. Mean head circumference percentile for males (50.1 ± 25.6) was significantly larger than females (43.4 ± 30.2). Micro- and macrocephaly were more frequent in ASD than expected (5.9%; 18.1%, respectively). Microcephaly in females (15.1%) was significantly more prevalent than in males (4.5%). The prevalence of macrocephaly in both sexes did not differ significantly. Regression was noted in 30.2% of the females with ASD, significantly higher than in males (18.9%). MNMD was documented in 73.8% of the females, significantly higher than in males (57.1%). M:F ratio decreased in a group with two or more phenotypes (3.6:1), while male predominance was more significant in the group without phenotypes (13.6:1). Neurological phenotypes associated with ASD are more prevalent in females than in males, resulting in more complex clinical and neurological manifesta- tions in females. -

EEG Microstate Complexity for Aiding Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer's

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN EEG microstate complexity for aiding early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease Luke Tait1,2,3,4*, Francesco Tamagnini5,6, George Stothart7, Edoardo Barvas8, Chiara Monaldini8, Roberto Frusciante8, Mirco Volpini8, Susanna Guttmann8, Elizabeth Coulthard9, Jon T. Brown6, Nina Kazanina10 & Marc Goodfellow1,2,3,11 The dynamics of the resting brain exhibit transitions between a small number of discrete networks, each remaining stable for tens to hundreds of milliseconds. These functional microstates are thought to be the building blocks of spontaneous consciousness. The electroencephalogram (EEG) is a useful tool for imaging microstates, and EEG microstate analysis can potentially give insight into altered brain dynamics underpinning cognitive impairment in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Since EEG is non-invasive and relatively inexpensive, EEG microstates have the potential to be useful clinical tools for aiding early diagnosis of AD. In this study, EEG was collected from two independent cohorts of probable AD and cognitively healthy control participants, and a cohort of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients with four-year clinical follow-up. The microstate associated with the frontoparietal working-memory/attention network was altered in AD due to parietal inactivation. Using a novel measure of complexity, we found microstate transitioning was slower and less complex in AD. When combined with a spectral EEG measure, microstate complexity could classify AD with sensitivity and specifcity > 80%, which was tested on an independent cohort, and could predict progression from MCI to AD in a small preliminary test cohort of 11 participants. EEG microstates therefore have potential to be a non-invasive functional biomarker of AD.