What Is the Functional / Organic Distinction Actually Doing in Psychiatry and Neurology?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Presentation and Care of a Family with Huntington Disease in a Resource

Charles et al. Journal of Clinical Movement Disorders (2017) 4:4 DOI 10.1186/s40734-017-0050-6 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Presentation and care of a family with Huntington disease in a resource-limited community Jarmal Charles1†, Lindyann Lessey1†, Jennifer Rooney1†, Ingmar Prokop1, Katherine Yearwood1, Hazel Da Breo1, Patrick Rooney1, Ruth H. Walker2,3 and Andrew K. Sobering1* Abstract Background: In high-income countries patients with Huntington disease (HD) typically present to healthcare providers after developing involuntary movements, or for pre-symptomatic genetic testing if at familial risk. A positive family history is a major guide when considering the decision to perform genetic testing for HD, both in affected and unaffected patients. Management of HD is focused upon control of symptoms, whether motor, cognitive, or psychiatric. There is no clear evidence to date of any disease-modifying agents. Referral of families and caregivers for psychological and social support, whether to HD-focused centers, or through virtual communities, is viewed as an important consequence of diagnosis. The experience of healthcare for such progressive neurodegenerative diseases in low- and middle-income nations is in stark contrast with the standard of care in high-income countries. Methods: An extended family with many members affected with an autosomal dominantly inherited movement disorder came to medical attention when one family member presented following a fall. Apart from one family member who was taking a benzodiazepine for involuntary movements, no other affected family members had sought medical attention. Members of this family live on several resource-limited Caribbean islands. Care of the chronically ill is often the responsibility of the family, and access to specialty care is difficult to obtain, or is unavailable. -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

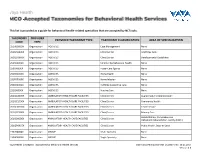

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

Parkinson's Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know

Parkinson’s Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know Edited by Gale Kittle, RN, MPH Parkinson’s Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know Table of Contents Chapter 1: Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic Understanding .....................................3 Chapter 2: Medical and Surgical Treatment Options ..........................................11 Chapter 3: Staying Well with Parkinson’s Disease ...............................................16 Chapter 4: Taking Charge of Your Health Care .....................................................22 Chapter 5: Accepting and Adapting to PD ..............................................................27 Chapter 6: Special Concerns of Persons with Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease ........................................................31 Glossary ........................................................................................................................36 About the National Parkinson Foundation ................................................................................38 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... 40 Parkinson’s Disease: What You and Your Family Should Know Chapter 1 Parkinson’s Disease’s: A Basic Understanding Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex disorder of the brain. Because it is a disease that affects the brain, it is classified as a neurological disorder – neurological means “related to the nerves” – and the doctors who specialize in diseases that affect the -

ABSTRACT Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

ADLN - Perpustakaan Universitas Airlangga ABSTRACT Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) was a disturbance of pervasife development in children characterized by the disturbance and delayed in cognitive, language, behaviour, communication, and social interaction. In the past 10 to 20 years, increased the number of autism currently reached an average of 8 persons among 1000 resident or 1:125. The cause of autism is is yet not found until now. The purpose of this research is analize risk factor of the trigger autism in children. This research used case control design. In the case category (ASD) accounted for 35 children according to record data in special school and the control category as many as 105 children taken from public school. Independent variables were genetic, premature, postmature, antenatal bleeding, maternal age of pregnancy, caesar childbirth, low birth weight (LBW), interval of pregnancy, organic brain syndrome, asphyxia, vaccination, smoking, consumtion of medicine and medicinal herbs, and spontaneous abortion. Whereas dependent variable was ASD incident. The data analysis by calculated odds ratio with 95% CI. The result of the research obtained were genetic, postmature, antenatal bleeding, caesar childbirth, low birth weight, interval of pregnancy, organic brain syndrome, asphyxia, vaccination, smoking, consumtion of medicine and medicinal herbs, spontaneous abortion was not the risk factor of the trigger ASD incident. The result obtained on the variables that significally premature (OR= 7.12 , 95% CI: 2.56<OR<26.07) which means that the children born prematurely had a 7.12 times higher for the onset of autism than children born with normal gestational age and another variable maternal age over 35 years (OR=8.58 , 95% CI: 1.30 <OR< 92.57) which means that the mother was pregnant at the age over 35 years had a 5.58 times higher risk to had children had autism than the mother who become pregnant less than 35 years. -

Eating Disorders

Eating Disorders NDSCS Counseling Services hopes the following information will help you gain a better understanding of eating disorders. If you believe you or someone you know is experiencing related concerns and would like to visit with a counselor, please call NDSCS Counseling Services for an appointment - 701.671.2286. Definition There is a commonly held view that eating disorders are a lifestyle choice. Eating disorders are actually serious and often fatal illnesses that cause severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may also signal an eating disorder. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Signs and Symptoms Anorexia nervosa People with anorexia nervosa may see themselves as overweight, even when they are dangerously underweight. People with anorexia nervosa typically weigh themselves repeatedly, severely restrict the amount of food they eat, and eat very small quantities of only certain foods. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. While many young women and men with this disorder die from complications associated with starvation, others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders. Symptoms include: • Extremely restricted eating • Extreme thinness (emaciation) • A relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a normal or healthy weight • Intense fear of gaining weight • Distorted body image, a self-esteem -

Understanding Mental Health

UNDERSTANDING MENTAL HEALTH WHAT IS MENTAL HEALTH? Our mental health directly influences how we think, feel and act: it also affects our physical health. Work, in fact, is actually one of the best things for protecting our mental health, but it can also adversely affect it. Good mental health and well-being is not an on-off A person’s mental health moves back and forth along this range during experience. We can all have days, weeks or months their lifetime, in response to different stressors and circumstances. At where we feel resilient, strong and optimistic, the green end of the continuum, people are well; showing resilience regardless of events or situations. Often that can and high levels of wellbeing. Moving into the yellow area, people be mixed with or shift to a very different set of may start to have difficulty coping. In the orange area, people have thoughts, feelings and behaviours; or not feeling more difficulty coping and symptoms may increase in severity and resilient and optimistic in just one or two areas of frequency. At the red end of the continuum, people are likely to be our life. For about twenty-five per cent of us, that experiencing severe symptoms and may be at risk of self-harm or may shift to having a significant impact on how suicide. we think, feel and act in many parts of our lives, including relationships, experiences at work, sense of connection to peer groups and our personal sense of worth, physical health and motivation. This could lead to us developing a mental health condition such as anxiety, depression, substance misuse. -

Prevalence and Classification of Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study Part 1

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Prevalence and Classification of Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study Part 1 Oscar L. Lopez, MD; William J. Jagust; Steven T. DeKosky, MD; James T. Becker, PhD; Annette Fitzpatrick, PhD; Corinne Dulberg, PhD; John Breitner, MD; Constantine Lyketsos, MD; Beverly Jones, MD; Claudia Kawas, MD; Michelle Carlson, PhD; Lewis H. Kuller, MD Objective: To examine the prevalence of mild cogni- was classified as either MCI amnestic-type or MCI mul- tive impairment (MCI) and its diagnostic classification tiple cognitive deficits–type. in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Cognition Study. Results: The overall prevalence of MCI was 19% (465 of 2470 participants); prevalence increased with age from Design: The CHS Cognition Study is an ancillary study 19% in participants younger than 75 years to 29% in those of the CHS that was conducted to determine the pres- older than 85 years. The overall prevalence of MCI at the ence of MCI and dementia in the CHS cohort. Pittsburgh center was 22% (130 of 599 participants); prevalence of the MCI amnesic-type was 6% and of the Setting: Multicenter population study. MCI multiple cognitive deficits–type was 16%. Patients: We examined 3608 participants in the CHS Conclusions: Twenty-two percent of the participants who had undergone detailed neurological, neuropsycho- aged 75 years or older had MCI. Mild cognitive impair- logical, neuroradiological, and psychiatric testing to iden- ment is a heterogenous syndrome, where the MCI am- tify dementia and MCI. nestic-type is less frequent than the MCI multiple cog- nitive deficits–type. Most of the participants with MCI Main Outcome Measures: The prevalence of MCI was had comorbid conditions that may affect their cognitive determined for the whole cohort, and specific subtypes functions. -

Curriculum Vitae Peter Robert Martin Address

CURRICULUM VITAE PETER ROBERT MARTIN ADDRESS: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital Suite 3035, 1601 23rd Avenue South Nashville, Tennessee 37232-8650 U.S.A. Phone: 615-343-4527 Mobile: 615-364-7175 E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2292-4741 WEBSITES: https://wag.app.vanderbilt.edu/PublicPage/Faculty/Details/27348 http://www.vanderbilt.edu/ics/ DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: September 6, 1949, Budapest, Hungary FAMILY: Married Barbara Ruth Bradford, December 23, 1985 Alexander Bradford Martin, born October 21, 1989 EDUCATION: 1967 - 1971 Honours B.Sc. (Molecular Genetics) McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 1971 - 1975 M.D., C.M. McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 1975 - 1976 Resident in Internal Medicine, Sunnybrook Medical Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 1976 - 1978 Research Fellow in Clinical Pharmacology, Clinical Pharmacology Program, Addiction Research Foundation Clinical Institute - Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto 1976 - 1979 M.Sc. (Pharmacology) University of Toronto Dissertation: Intravenous phenobarbital treatment of barbiturate and other hypnosedative withdrawal: A pharmacokinetic approach. 1978 - 1979 Resident in Psychiatry, Affective Disorders Unit, Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, University of Toronto 1979 Resident in Psychiatry, Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto 1980 Resident in Psychiatry, Toronto General Hospital, University of Toronto LICENSURE AND CERTIFICATION: The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (License No. 28907), 1976. The Board of Medical Examiners of the State of Maryland (License No. D26685), 1981. The Board of Medical Examiners of the State of Tennessee (License No. MD17128), 1986. Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (Canada), Psychiatry, 1981.