Is the Requirement of Dishonesty Always the Best Policy to Estabish Liability Against Those Who Assist in a Breach of Trust?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagereal Capture

Some Aspects of Theft of Computer Software by M. Dunning I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to test the capability of New Zealand law to adequately deal with the impact that computers have on current notions of crimes relating to property. Has the criminal law kept pace with technology and continued to protect property interests or is our law flexible enough to be applied to new situations anyway? The increase of the moneyless society may mean a decrease in money motivated crimes of violence such as robbery, and an increase in white collar crime. Every aspect of life is being computerised-even our per sonality is on character files, with the attendant )ossibility of criminal breach of privacy. The problems confronted in this area are mostly definitional. While it may be easy to recognise morally opprobrious conduct, the object of such conduct may not be so easily categorised as criminal. A factor of this is a general lack of understanding of the computer process, so this would seem an appropriate place to begin the inquiry. II. THE COMPUTER Whiteside I identifies five key elements in a computer system. (1) Translation of data into a form readable by the computer, called input; and subject to manipulation by the introduction of false data. Remote terminals can be situated anywhere outside the cen tral processing unit (CPU), connected by (usually) telephone wires over which data may be transmitted, e.g. New Zealand banks on line to Databank. Outside users are given a site code number (identifying them) and an access code number (enabling entry to the CPU) which "plug" their remote terminal in. -

Chapter 8 Criminal Conduct Offences

Chapter 8 Criminal conduct offences Page Index 1-8-1 Introduction 1-8-2 Chapter structure 1-8-2 Transitional guidance 1-8-2 Criminal conduct - section 42 – Armed Forces Act 2006 1-8-5 Violence offences 1-8-6 Common assault and battery - section 39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-6 Assault occasioning actual bodily harm - section 47 Offences against the Persons Act 1861 1-8-11 Possession in public place of offensive weapon - section 1 Prevention of Crime Act 1953 1-8-15 Possession in public place of point or blade - section 139 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-17 Dishonesty offences 1-8-20 Theft - section 1 Theft Act 1968 1-8-20 Taking a motor vehicle or other conveyance without authority - section 12 Theft Act 1968 1-8-25 Making off without payment - section 3 Theft Act 1978 1-8-29 Abstraction of electricity - section 13 Theft Act 1968 1-8-31 Dishonestly obtaining electronic communications services – section 125 Communications Act 2003 1-8-32 Possession or supply of apparatus which may be used for obtaining an electronic communications service - section 126 Communications Act 2003 1-8-34 Fraud - section 1 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-37 Dishonestly obtaining services - section 11 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-41 Miscellaneous offences 1-8-44 Unlawful possession of a controlled drug - section 5 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 1-8-44 Criminal damage - section 1 Criminal Damage Act 1971 1-8-47 Interference with vehicles - section 9 Criminal Attempts Act 1981 1-8-51 Road traffic offences 1-8-53 Careless and inconsiderate driving - section 3 Road Traffic Act 1988 1-8-53 Driving -

Itu Toolkit for Cybercrime Legislation

International Telecommunication Union Cybercrime Legislation Resources ITU TOOLKIT FOR CYBERCRIME LEGISLATION Developed through the American Bar Association’s Privacy & Computer Crime Committee Section of Science & Technology Law With Global Participation ICT Applications and Cybersecurity Division Policies and Strategies Department ITU Telecommunication Development Sector Draft Rev. February 2010 For further information, please contact the ITU-D ICT Applications and Cybersecurity Division at [email protected] Acknowledgements We are pleased to share with you a revised version of the ITU Toolkit for Cybercrime Legislation. This version reflects the feedback received since the launch of the Toolkit in May 2009. If you still have input and feedback on the Toolkit, please do not hesitate to share this with us in the BDT’s ICT Applications and Cybersecurity Division at: [email protected]. (The deadline for input on this version of the document is 31 July 2010.) This report was commissioned by the ITU Development Sector’s ICT Applications and Cybersecurity Division. The ITU Toolkit for Cybercrime Legislation was developed by the American Bar Association’s Privacy & Computer Crime Committee, with Jody R. Westby as the Project Chair & Editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the ITU and the American Bar Association. Denominations and classifications employed in this publication do not imply any opinion concerning the legal or other status of any territory or any endorsement or acceptance of any boundary. Where the designation "country" appears in this publication, it covers countries and territories. The ITU Toolkit for Cybercrime Legislation is available online at: www.itu.int/ITU-D/cyb/cybersecurity/legislation.html This document has been issued without formal editing. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Drake, P J Is the requirement of dishonesty always the best policy to estabish liability against those who assist in a breach of trust? Original Citation Drake, P J (2011) Is the requirement of dishonesty always the best policy to estabish liability against those who assist in a breach of trust? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/11652/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ IS THE REQUIREMENT OF DISHONESTY ALWAYS THE BEST POLICY TO ESTABLISH LIABILITY AGAINST THOSE WHO ASSIST IN A BREACH OF TRUST? Philip J Drake A dissertation submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Laws (LLM) The University of Huddersfield May 2011 . -

Fraud in England and Wales

Fraud in England and Wales AN INTRODUCTION TO UK LEGISLATION | JULY 2020 | SECOND EDITION The way in which criminal fraud is defined, investigated and prosecuted differs across the UK. This guide explains how fraud is usually dealt with under the criminal law in England and Wales. WHAT IS FRAUD? • When a person has in their • the common law offence of possession or under their control, any conspiracy to defraud; and Fraud can be broadly defined as the article for use in the course of, or in deliberate use of deception or dishonesty • offences under the Bribery Act 2010; connection with, any fraud (s6). to disadvantage or cause loss (usually Computer Misuse Act 1990; Forgery financial) to another person or party. • When a person makes, adapts, and Counterfeiting Act 1981; Identity Definitions of fraud vary from country to supplies or offers to supply any Documents Act 2010; Proceeds of country and between legal systems. article knowing that it is designed or Crime Act 2002; or the Financial In England and Wales fraud can be dealt adapted for use in fraud, or intended Services and Markets Acts 2000 with through the criminal justice system, to be used to commit fraud (s7). and 2012. the civil justice system, or both. This • When a person knowingly guide explains the criminal process only. participates in a business which CIVIL FRAUD is carried on with the intention of OVERVIEW OF THE LAW defrauding creditors or for any other Conduct which may constitute a In England and Wales, criminal fraud is fraudulent purpose (s9). criminal fraud can also result in civil mainly dealt with in the Fraud Act 2006 Offences under ss2, 3 and 4 require liability. -

Fraud Act 2006 (C

10/23/2014 Fraud Act 2006 (c. 35) xmlns:atom="http://www.w3.org/2005/Atom" xmlns:atom="http://www.w3.org/2005/Atom" Fraud Act 2006 2006 CHAPTER 35 An Act to make provision for, and in connection with, criminal liability for fraud and obtaining services dishonestly. [8th November 2006] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— Fraud 1 Fraud (1) A person is guilty of fraud if he is in breach of any of the sections listed in subsection (2) (which provide for different ways of committing the offence). (2) The sections are— (a) section 2 (fraud by false representation), (b) section 3 (fraud by failing to disclose information), and (c) section 4 (fraud by abuse of position). (3) A person who is guilty of fraud is liable— (a) on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months or to a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (or to both); (b) on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years or to a fine (or to both). (4) Subsection (3)(a) applies in relation to Northern Ireland as if the reference to 12 months were a reference to 6 months. 2 Fraud by false representation (1) A person is in breach of this section if he— (a) dishonestly makes a false representation, and (b) intends, by making the representation— (i) to make a gain for himself or another, or (ii) to cause loss to another or to expose another to a risk of loss. -

Dr. Robert Trossel Loses Medical License

FITNESS TO PRACTISE PANEL 11 JANUARY – 5 MARCH 2010 27 MARCH 2010; 10-11 APRIL 2010 6 – 10 & 27 – 29 SEPTEMBER 2010 Regent’s Place, 350 Euston Road, London, NW1 3JN Name of Respondent Doctor: Dr Robert Theodore Henri Kees TROSSEL Registered Qualifications: Artsexamen 1980 Universiteit te Leiden Registration Number: 6049460 Type of Case: New case of impairment by reason of: misconduct; caution and conviction Panel Members: Professor B Gomes da Costa, Chairman (Lay) Mrs M Bamford (Lay) Dr S Pande (Medical) Mrs S Pond (Lay) Ms E Tessler (Lay) Legal Assessor: Mr R Hay (Days 1 – 41 & 47 - 49) Mr D Mason (Days 42 - 46) Secretary to the Panel: Ms J Hazell (Days 1 to 46) Mr A Elliott (Days 47 – 49) Representation: GMC: Mr Tom Kark, Counsel, instructed by Field Fisher Waterhouse, represented the General Medical Council. Doctor: Dr Trossel was present and was represented by Mr Robert Jay, QC, instructed by Eastwoods Solicitors. ALLEGATION That being registered under the Medical Act 1983, as amended, 1. At all material times you were a medical practitioner with consulting rooms at 57a New Cavendish Street, London, 15a Wimpole St, London and in Rotterdam, Holland; Amended to read: At all material times you were a medical practitioner with consulting rooms at 57a Wimpole St, London and in Rotterdam, Holland; Admitted as amended and found proved. 1 Patient A 2. On or about 17 10 August 2004 you had a consultation in Rotterdam with Patient A, Admitted, as amended, and found proved i. Patient A suffered from Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Admitted and found proved ii. -

Banding of Offences in the Advocates' Graduated Fee Scheme

Banding of Offences in the Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (AGFS) Version 1.1 February 2018 Banding of Offences in the Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (AGFS) Version 1.1 This information is also available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/banding-of-offences-in-the-advocates-graduated-fee- scheme Banding of Offences in the Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (AGFS) Contents Introduction 2 Table A 3 Table B 8 1 Banding of Offences in the Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (AGFS) Introduction This document sets out the banding of offences under the reformed Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (the "AGFS"), in force from 1 April 2018. The principal legislation which provides for the AGFS is the Criminal Legal Aid (Remuneration) Regulations 2013 (S.I. 2013/435); in particular, see Schedule 1 to those Regulations. The bands are set out in Table B of this document, which should be read in conjunction with Table A. Where the band within which an offence described in Table B in this document falls depends on the facts of the case, the band within which the offence falls is to be determined by reference to Table A. In Table A and Table B, "category" is used to provide a broad, overarching description for a range of similar offences which fall within a particular group or range of bands. 2 Banding of Offences in the Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (AGFS) Table A Category Description Bands 1 Murder/Manslaughter Band 1.1: Killing of a child (16 years old or under); killing of two or more persons; killing of a police officer, prison officer or equivalent public servant in the course of their duty; killing of a patient in a medical or nursing care context; corporate manslaughter; manslaughter by gross negligence; missing body killing. -

List of Criminal Offences

Criminal offences Offence Contrary to Year and chapter Class A: Homicide and related grave offences Murder Common law Manslaughter Common law Soliciting to commit murder Offences against the 1861 c. 100 Person Act 1861 s.4 Child destruction Infant Life (Preservation) 1929 c. 34 Act 1929 s.1(1) Infanticide Infanticide Act 1938 s.1(1) 1938 c. 36 Causing explosion likely to endanger life or Explosive Substances Act 1883 c. 3 property 1883 s.2 Attempt to cause explosion, making or keeping Explosive Substances Act as above explosive etc. 1883 s.3 Class B: Offences involving serious violence or damage, and serious drugs offences Endangering the safety of an aircraft Aviation Security Act 1982 1982 c. 36 s. 2(1)(b) Racially-aggravated arson (not endangering life) Crime and Disorder Act 1998 c. 37 1998 s. 30(1) Kidnapping Common law False imprisonment Common law Aggravated criminal damage Criminal Damage Act 1971 1971 c. 48 s.1(2) Aggravated arson Criminal Damage Act 1971 as above s.1(2), (3) Arson (where value exceeds £30,000) Criminal Damage Act 1971 as above s.1(3) Possession of firearm with intent to endanger life Firearms Act 1968 s.16 1968 c. 27 Use of firearm to resist arrest Firearms Act 1968 s.17 as above Possession of firearm with criminal intent Firearms Act 1968 s.18 as above Possession or acquisition of certain prohibited Firearms Act 1968 s.5 as above weapons etc. Aggravated burglary Theft Act 1968 s.10 1968 c. 60 Armed robbery Theft Act 1968 s.8(1) as above Assault with weapon with intent to rob Theft Act 1968 s.8(2) as above Blackmail Theft Act 1968 s.21 as above Riot Public Order Act 1986 s.1 1986 c. -

Theft Offences Definitive Guideline for Reference Only

For reference only. Please refer to the guideline(s) on the Sentencing Council website: www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk Theft Offences Definitive Guideline GUIDELINE DEFINITIVE For reference only. Please refer to the guideline(s) on the Sentencing Council website: Contents www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk Applicability of guideline 2 General theft 3 (all section 1 offences excluding theft from a shop or stall) Theft Act 1968 (section 1) Theft from a shop or stall 9 Theft Act 1968 (section 1) Handling stolen goods 15 Theft Act 1968 (section 22) Going equipped for theft or burglary 21 Theft Act 1968 (section 25) Abstracting electricity 25 Theft Act 1968 (section 13) Making off without payment 29 Theft Act 1978 (section 3) Annex: Fine bands and community orders 35 © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Effective from 1 February 2016 2 Theft Offences Definitive Guideline For reference only. Please refer to the guideline(s) on the Sentencing Council website: www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk Applicability of guideline n accordance with section 120 of the Coroners Structure, ranges and starting points and Justice Act 2009, the Sentencing Council For the purposes of section 125(3)–(4) of the Iissues this definitive guideline. -

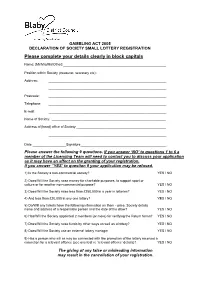

Gambling Act 2005 Declaration of Society Small Lottery Registration

GAMBLING ACT 2005 DECLARATION OF SOCIETY SMALL LOTTERY REGISTRATION Please complete your details clearly in block capitals Name: [Mr/Mrs/Ms/Other] __________________________________________________ Position within Society (treasurer, secretary etc):_____________________________________ Address: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Postcode: _______________________________________________________________ Telephone: _______________________________________________________________ E-mail: _______________________________________________________________ Name of Society: _____________________________________________________________ Address of [head] office of Society:________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Date __________________Signature______________________________________________ Please answer the following 9 questions. If you answer ‘NO’ to questions 1 to 6 a member of the Licensing Team will need to contact you to discuss your application as it may have an affect on the granting of your registration. If you answer ‘’YES’ to question 9 your application may be refused. 1) Is the Society a non-commercial society? YES / NO 2) Does/Will the Society raise money for charitable purposes, to support sport or culture or for another non-commercial purpose? YES / NO 3) Does/Will the Society raise less than £250,000 in a year in lotteries? YES / NO 4) And less than £20,000 in any one lottery? -

Visiting Forces Act 1952 (C

Visiting Forces Act 1952 (c. 67) 1 SCHEDULE – Offences referred to in s. 3 Document Generated: 2021-08-08 Status: Point in time view as at 27/04/1997. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Visiting Forces Act 1952, SCHEDULE. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULE OFFENCES REFERRED TO IN S. 3 1 In the application of section three of this Act to England and Wales and to Northern Ireland, the expression “offence against the person” means any of the following offences, that is to say:— (a) murder, manslaughter, rape [F1, torture], buggery [F2robbery] and assault [F3and any offence of aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring suicide or an attempt to commit suicide]; and (b) any offence not falling within the foregoing sub-paragraph, being an offence punishable under any of the following enactments:— (i) the Offences against the M1Person Act, 1861, except section fifty- seven thereof (which relates to bigamy); F4(ii) the M2Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885; (iii) the M3Punishment of Incest Act, 1908; (iv) . F5 section eighty- nine of the M4Mental Health Act (Northern Ireland), 1948 (which relate respectively to certain offences against mentally defective females); (v) . F6 (vi) sections one to five and section eleven of the M5Children and Young Persons Act, 1933, and sections eleven, twelve, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen and twenty-one of the M6Children and Young Persons Act (Northern Ireland), 1950; and (vii) the M7Infanticide Act, 1938 and the M8Infanticide Act (Northern Ireland), 1939. [F7and (vii)