An Island to Oneself by Tom Neale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spartan Daily, October 8, 2014

Drop by spartandaily.com for SJSU Humanities' 60th birthday on Weather Foggy Hi o 82 MICROSOFT GIVES STARTUPS CONVENE AT CHANGE AND THE Spartan Lo o OFFICE TO STUDENTS SJSU FOR TECHMANITY ART OF PROTESTING 52 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 5 Video Volume 143 | Issue 18 Serving San José State University since 1934 Wednesday, October 8, 2014 California Faculty Association calls for higher wages By Sonya Herrera Kelly Harrison, an English and general @Sonya_M_Herrera engineering lecturer, said she was glad she attended Monday’s CFA meeting. Anthropology professor Jonathan Karpf “Jonathan gave a great presentation with some repeated the call for action to his colleagues at of the data of what the choices are,” Harrison said. the California Faculty Association meeting on Included in Karpf’s presentation was a Monday. “thought experiment” on what CFA members “We’ve come down since we started; they would want to do in case the Chancellor’s office haven’t budged,” Karpf said. “That alone is reason was unwilling to meet the CFA’s demands. for us to say, ‘What gives?’” “I was basically trying to take a temperature of According to Karpf, the purpose of Monday’s the mood of the faculty,” Karpf said. CFA meeting was to inform San Jose State He posed the question of which option would University faculty on the inadequacy of the latest be best: to strike and attempt to resolve the salary offer made by the CSU chancellor’s office. disagreement immediately, or to accept the first “We need them to offer a little bit more than year’s salary offer while retaining the ability to they’re offering,” Karpf said. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Macdougall'14 Can't Kick the Habit

OCTOBER 24, 2014 THE BACHELOR THE STUDENT VOICE OF WABASH COLLEGE SINCE 1908 MACDOUGALL‘14 CAN’T KICK THE HABIT GRADUATE SCHOOL AT PURDUE BRINGS KICKING OPPORTUNITY FOR FORMER LITTLE GIANT DEREK ANDRE ‘16 | SPORTS EDITOR • Graduate school is not a new concept for Wabash men. Playing Big Ten football while going to graduate school, however, probably is. For three years, Ian MacDougall ’14 donned the scarlet and white on Saturday mornings to handle the kicking duties for the Little Giant Football team. During his time at Wabash, MacDougall set new records for field goals made in a season (15), extra points made in a season (55), and extra points made in a career (125). MacDougall was also First Team All-NCAC in his senior year. However, once his senior season was com- pleted, MacDougall was informed by multiple members of the Athletic Department that he had a remaining year of eligibility, should he choose to use it. ““It was around Christmas time,” MacDougall said. “Wabash was playing somebody in basketball and I had to come back from break to call the game and Mark Colton said ‘you realize you have an extra year of eligibility.’ I kind of chuckled at it. Then, after the game, I asked Joe Haklin and he said ‘yeah, that actually works out, you do.’” After toying with aremaining at Wabash for an extra semes- ter, MacDougall began to look at graduate school. The oppor- tunity to get a masters degree while playing football seemed enticing to him. That’s when the door to Purdue opened. -

Monterey Jazz Festival Next Generation Orchestra

March / April 2017 Issue 371 now in our 43rd year jazz &blues report MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL NEXT GENERATION ORCHESTRA March • April 2017 • Issue 371 MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL jazz NEXT GENERATION ORCHESTRA &blues report Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Layout & Design Bill Wahl Operations Jim Martin Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. RIP JBR Writers Tom Alabiso, John Hunt, Chris Colombi, Mark A. Cole, Hal Hill Check out our constantly updated website. All of our issues from our first PDFs in September 2003 and on are posted, as well as many special issues with festival reviews, Blues Cruise and Gift Guides. Now you can search for CD Re- views by artists, titles, record labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 years of reviews are up from our archives and we will be adding more, especially from our early years back to 1974. 47th Annual Next Generation Jazz Festival Presented by Monterey Jazz Festival Hosts Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com Web www.jazz-blues.com America’s Top Student Jazz Musicians, Copyright © 2017 Jazz & Blues Report March 31-April 2 in Monterey CA No portion of this publication may be re- Monterey, Calif., March 1, 2017; The 47th Annual Next Generation Jazz produced without written permission from Festival Presented by Monterey Jazz Festival takes place March 31- April 2, the publisher. All rights Reserved. 2017 in downtown Monterey. The weekend-long event includes big bands, Founded in Buffalo New York in March of combos, vocal ensembles, and individual musicians vying for a spot on the 1974; began our Cleveland edition in April of 1978. -

THE COWL Order Sheets, but She Says, “Good Food Is Alumni Food Court Completed the New OBC Grill Has Fresher Burgers and a Wider Variety of Toppings

TheVol. LXXIX No. 2 @thecowl • thecowl.com ProvidenceCowl College September 11, 2014 UNITED WE STAND REMEMBERING 9/11 by Nicole Corbin ’15 Opinion Editor remembrance On Tuesday morning, September 11, 2001, Mrs. Loffredo’s third grade class strolled into the classroom still buzzing with start-of-the-new-school-year excitement. It was a beautiful late-summer day in Rhode Island. By the time we settled in to start our timetables at 9 a.m., Flight 11 had already struck the North Tower of the World Trade Center. Our day continued on like any other school day: reading, science, recess, practicing writing in cursive. It wasn’t until I stepped off the school bus and arrived home that I had learned what happened in New York City. There are two things that I distinctly remember. The first thing was being sat down by my mother and hearing her explain that the buildings were attacked by terrorists; meanwhile, on the television in the living room, the news recounted the day’s events as the Twin Towers smoked and collapsed on screen. My 8-year-old mind could not quite process what she was telling me. I imagined Acme bombs attacking the buildings in Looney Tunes fashion. My family was fortunate enough to not have been personally impacted by the tragedy, but I still struggled to grapple with the full scope of what had occurred, and like any child, I questioned why? The terrorists. That was the reason I was given, and that was the reason I accepted. I didn’t know who they were or what they wanted, but I knew that they had attacked my country, my home. -

![+Digital Booklet]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0439/digital-booklet-6390439.webp)

+Digital Booklet]

Everything Will Be Alright In The End [+digital booklet] Looking at a new Weezer project is one kind of people unusual cases when its alright to bust the guideline for possibly not reviewing a record to the artist's earlier functions. Their own first 2 documents (Blue & Pinkerton) ended up great that your drop in good quality during subsequent secretes leaves their particular fans within a pandemonium, today, Eighteen several years eventually. There are plenty of rings of which get rid of its benefit increasingly more then there is honestly no problem to be able. The primary reason Weezer's die hard fans have this specific grudge happens because Canals Cuomo, the actual group's frontman and process songwriter, provides regularly on the surface accepted that he is wanting to prepare audio this is not like her first work. Pinkerton's commercial breakdown was obviously a adequate strike that will Cuomo's self confidence which he discontinued relying his or her imaginative norms of behavior along with attempted posting tunes that you will find well known. Coming from 2002 * The year 2010, Weezer release Six facilities albums, which all ended up being bashed because of not residing to the requirements recently establish by The Orange Lp in addition to Pinkerton. These folks were charged with simply being emotionless, idle, thoughtless, along with poor on the music the band was previously find out to form. In saying that though, there had been several jewels uncovered among the now. Although tracks just like Isle in the sunshine and Pig in addition to Beans were not stuffed with the particular musical show the nature along with lyrical guru in their birth, these folks were big hits in addition to get noticed music. -

Books-Library.Online-01120741Zt2g0

The Shack A novel by William P. Young In collaboration with Wayne Jacobsen and Brad Cummings CONTENTS Foreword 1. A Confluence of Paths 2. The Gathering Dark 3. The Tipping Point 4. The Great Sadness 5. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner 6. A Piece of π 7. God on the Dock 8. A Breakfast of Champions 9. A Long Time Ago, In a Garden Far, Far Away 10. Wade in the Water 11. Here Come Da Judge 12. In the Belly of the Beasts 13. A Meeting of hearts 14. Verbs and Other Freedoms 15. A Festival of Friends 16. A Morning of Sorrows 17. Choices of the Heart 18. Outbound Ripples After Words Acknowledgements The Missy Project F OREWORD Who wouldn’t be skeptical when a man claims to have spent an entire weekend with God, in a shack no less? And this was the shack. I have known Mack for a bit more than twenty years, since the day we both showed up at a neighbor’s house to help him bale a field of hay to put up for his couple of cows. Since then he and I have been, as the kids say these days, hangin’ out, sharing a coffee— or for me a chai tea, extra hot with soy. Our conversations bring a deep sort of pleasure, always sprinkled with lots of laughs and once in a while a tear or two. Frankly, the older we get, the more we hang out, if you know what I mean. His full name is Mackenzie Allen Phillips, although most people call him Allen. -

Songs from Orion

Songs from Orion by John Eckalbar Songs from Orion © 2006 by John Eckalbar All rights reserved Permission to reproduce copies, except excerpts for reviews, is prohibited unless given in writing by the author: John Eckalbar Chico, California (530) 343-6791 [email protected] Songs from Orion is posted on the Forum page of the Heidelberg Graphics Web site: www.HeidelbergGraphics.com in Chico, California, for the enjoyment of readers. It may not be copied or reprinted except for personal reading. Several people deserve thanks for their help on this project. My wife, Anne, my sister, Mary Glazer, and my friends Laurence Boag and John Elstrott all read early versions of the manuscript and got me to believe that I should stick with it. My great friend David Crosby did the same, and I doubt that I would have kept at it except for their encouragement. Ernie Brace, a POW captured in Laos and released in Hanoi, was kind enough to read the sections on the MIA/POW experience. Capt. Zeke Cormier and Mr. Joe Ciokin arranged for me to fly out to the USS Constellation and the USS Carl Vinson to see what carrier catapult shots are like. And my son, Walter, both inspired and proofread the sections on wrestling. The Songs of Orion Preface ............................................................................................................................... 6 The Spirit of Orion........................................................................................................... 14 Martin Landry................................................................................................................. -

The Tiger Vol. 108 Issue 28 2014-10-07

mmmmm MM wmmmm Is Death Valley Really IN THIS ISSUE Sustainable? I outlook History I sports Art Ms demon I Timeout B1 C1 01 5l*The mw mvm our NICE I WEEK look for The Tiger on Tuesday* and Thursday* «H October 7,2014 TIGER Established in 1907, South Carolina's oldest college newspaper roars for Clemson. volume 108 0/thetigernews 0/@thetigercu Gthetigernews.com IFC: University to lift ban on IFC fraternities Twenty four chapters to regain privileges Oct. 10. Evan Senken Council chapters (IFC) were by continuing to follow the the fraternities that haven't be reinstated in time for email about the suspension Asst. News Editor suspended after numerous rules set in place for Greek done anything wrong not be homecoming where the being lifted, Gail DiSabatino, instances of misconduct, but Life on campus. Fraternities punished. I'm sure they're chapters build floats displayed the vice president for Student After spending a little over the temporary policy gives that are not in good standing glad to be reinstated and back on Bowman field. These Affairs said, "A comprehensive, a week on suspension, Clemson the fraternities a route to with Clemson must continue to normal." attractions always draw a large long-term plan is under has planned to conditionally regain privileges. The campus- to abide by any sanction or To retain privileges, all crowd of students, parents, development to enhance lift the ban on 24 fraternities' wide email detailed how probation other than the IFC chapters must meet with the children and alumni on the days the Greek culture of safety social and new member fraternities both in good and wide suspension, follow a Student Affairs staff to have before and on homecoming. -

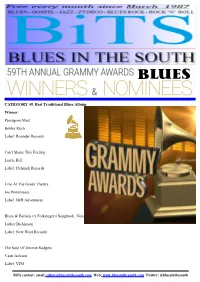

Bits Contact: Email: [email protected] Web: Twitter: @Bluesinthesouth CATEGORY 50

BLUES CATEGORY 49. Best Traditional Blues Album Winner Porcupine Meat Bobby Rush Label: Rounder Records Can't Shake This Feeling Lurrie Bell Label: Delmark Records Live At The Greek Theatre Joe Bonamassa Label: J&R Adventures Blues & Ballads (A Folksinger's Songbook: Volumes I & II) Luther Dickinson Label: New West Records The Soul Of Jimmie Rodgers Vasti Jackson Label: VJM BiTS contact: email: [email protected] Web: www.bluesinthesouth.com Twitter: @bluesinthesouth CATEGORY 50. Best Contemporary Blues Album Winner The Last Days Of Oakland Fantastic Negrito Label: Believe Global/Blackball Universe Love Wins Again Janiva Magness Label: Blue Élan Records Bloodline Kenny Neal Label: Cleopatra Blues Give It Back To You The Record Company Label: Concord Records Everybody Wants A Piece Joe Louis Walker Label: Provogue BLUES GIGS: FROM EXMOUTH TO EASTBOURNE AND A BIT MORE BESIDES - M A R C H 2017 02 JINDER @ THE PLATFORM TAVERN, TOWN QUAY, SOTON 02 1:00PM - 11:00PM* SWANAGE BLUES FESTIVAL - SWANAGE, DORSET 03 PLATFORM POSSE @ THE PLATFORM TAVERN, SOTON 03 RIVERSIDE BLUES BAND @ THE ANCHOR, HIGH ST@ THE PLATFORM TAVERN, TOWN QUAY, SOTON, SWANAGE BLUES FESTIVAL, 03 JO HARMAN AT THE 1865, SOUTHAMPTON, 03 1:00PM - 11:00PM* SWANAGE BLUES FESTIVAL - SWANAGE, DORSET - 18 INDOORS VENUES, 70 GIGS, JAMS AND OPEN MICS 04 PETE HARRIS BLUES BAND @ EAST BAR, HIGH ST. SWANAGE 12.30PM 04 RUBY AND THE ROUGHCUTS @ THE PLATFORM TAVERN, SOTON 04 STAN'S BLUES JAMBOREE @ SWANAGE BLUES FESTIVAL, THE LEGION, 152 HIGH STREET, SWANAGE BH19 2PA, 04 1:00PM - 11:00PM* SWANAGE BLUES FESTIVAL - SWANAGE, DORSET - 18 INDOORS VENUES, 70 GIGS, JAMS AND OPEN MICS , 05 PETE HARRIS AND JON VAUGHAN @ THE RED LION, HIGH ST. -

AA-Postscript.Qxp:Layout 1

37 TUESDAY, AUGUST 12, 2014 LIFESTYLE Gossip Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo admits band mistakes eezer frontman Rivers Cuomo admits he feels terrible for taking the group in the Wwrong musical direction in the past. The 44-year-old singer pours his heart out on the group’s upcoming single ‘Back To The Shack’, on which he admits he hasn’t always made the right decisions on behalf of the ‘Buddy Holly’ hitmakers and at times he went too far. He said: “Lyrically I’m talking about how I feel bad about some of the musical experiments I took Weezer on and how I want to make a classic alt-rock record. “Sometimes I’ve gone over the edge. Right now it feels like we want to go back and bal- ance it out with some more classic elements of geek rock. “There’s definitely still some experimentation but it sounds like experiments that only Weezer could do.” Rivers also used his feelings to help inspire him to pen Weezer’s upcoming ninth album, ‘Everything Will Be Alright In The End’, which partly focuses on the group’s relationship with father-fig- ures. He added to NME magazine: “My father was in the army, stationed in Germany, when I was growing up, so I didn’t see him much. That gave me a lot to write about, and I explored the father figure theme in other ways, too. There’s a song called ‘Eulogy For A Rock Band’ about Weezer’s musical forefathers. ‘The British Are Coming’ is about the American colonies’ relations with their imperial father, the British Empire. -

FFRF Blocks Giveaway for Church Repairs an Alaska City Wisely Chose Not to Dole out Money to a Local Church After the FFRF Raised Objections to the Proposed Move

Julia Sweeney’s Do you know an FFRF’s guide to religious American Indian Winter Solstice movies atheist? celebration! PAGES 10-12 PAGES 13-14 PAGE 24 Vol. 35 No. 1 Published by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc. January / February 2018 ‘A’ is for awesome (and atheist and agnostic)! FFRF blocks giveaway for church repairs An Alaska city wisely chose not to dole out money to a local church after the FFRF raised objections to the proposed move. The Sitka City Assembly was prepared to allocate $5,000 from the city’s Visitor’s Enhancement Fund to help repair St. Michael’s Cathedral. City Attorney Bri- an Hanson had reviewed concerns that funding this church would violate the First Amendment and initially (and er- roneously) concluded that the grant would be permissible. FFRF challenged this assessment. Han- Photo by Kimberley Haas/Union Leader Correspondent son failed to properly After getting approval from the city of Somersworth, N.H., FFRF Member Richard Gagnon raises the ‘A’ apply the Supreme flag next to a Ten Commandments monument on city property on Jan. 2. See story on page 7. Court’s 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) test. Other cases have shown that Lemon’s second prong (that a Most productive year ever for FFRF! governmental action’s Legal Department scholars across the country for tal consisted of letters warning 350 principal or primary effect must neither ad- legal advice. school districts across the United Shutterstock photo earns more than vance nor inhibit reli- States against allowing the Todd St. Michael’s Cathedral in gion) does not allow 300 victories State/church complaints Becker Foundation into public Sitka, Alaska, will not be grants that support re- Over the past year, FFRF schools to convert students.