Jesus' Cry of Dereliction: Why the Father Did Not Turn Against Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer 'Dating the Death of Jesus' Citation for published version: Bond, H 2013, ''Dating the Death of Jesus': Memory and the Religious Imagination', New Testament Studies, vol. 59, no. 04, pp. 461-475. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688513000131 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0028688513000131 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: New Testament Studies Publisher Rights Statement: © Helen Bond, 2013. Bond, H. (2013). 'Dating the Death of Jesus': Memory and the Religious Imagination. New Testament Studies, 59(04), 461-475doi: 10.1017/S0028688513000131 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Dating the Death of Jesus: Memory and the Religious Imagination Helen K. Bond School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh, Mound Place, Edinburgh, EH1 2LX [email protected] After discussing the scholarly preference for dating Jesus’ crucifixion to 7th April 30 CE, this article argues that the precise date can no longer be recovered. All we can claim with any degree of historical certainty is that Jesus died some time around Passover (perhaps a week or so before the feast) between 29 and 34 CE. -

Read Books and Watch Movies

BOOKS FOR ADULTS Black Feminist Thought The Fire Next Time by Patricia Hill Collins by James Baldwin Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration Discovers Her Superpower in the Age of Colorblindness by Dr. Brittney Cooper by Michelle Alexander Heavy: An American Memoir The Next American Revolution: by Kiese Laymon Sustainable Activism for the Twenty- First Century I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Grace Lee Boggs by Maya Angelou The Warmth of Other Suns Just Mercy by Isabel Wilkerson by Bryan Stevenson Their Eyes Were Watching God Redefining Realness by Zora Neale Hurston by Janet Mock This Bridge Called My Back: Writings Sister Outsider by Radical by Audre Lorde Women of Color So You Want to Talk About Race by Cherríe Moraga by Ijeoma Oluo White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for The Bluest Eye White People to Talk About Racism by Toni Morrison by Robin DiAngelo, PhD FILMS AND TV SERIES FOR ADULTS: 13th (Ava DuVernay) Fruitvale Station (Ryan Coogler) — Netflix — Available to rent American Son (Kenny Leon) I Am Not Your Negro (James Baldwin doc) — Netflix — Available to rent or on Kanopy Black Power Mixtape: 1967-1975 If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins) — Available to rent — Hulu Clemency (Chinonye Chukwu) Just Mercy (Destin Daniel Cretton) — Available to rent — Available to rent Dear White People (Justin Simien) King In The Wilderness — Netflix — HBO STOMPOUTBULLYING.ORG FILMS AND TV SERIES FOR ADULTS: See You Yesterday (Stefon Bristol) The Hate U Give (George Tillman Jr.) — Netflix — Hulu with Cinemax Selma (Ava DuVernay) When They See Us (Ava DuVernay) — Available to rent — Netflix The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the 12 Years The Slave Revolution — Hulu — Available to rent BOOKS FOR KIDS Why?: A Conversation about Race A Picture Book of Sitting Bull Taye Diggs David A. -

The Historical Origins of Antisemitism

THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF ANTISEMITISM …Let me give you my honest advice. First, their synagogues or churches should be set on fire, and whatever does not burn up should be covered or spread over so that no one may ever be able to see a cinder of it. And this ought to be done for the honor of God and Christianity… (Martin Luther, 1543) When Wilhelm Marr, a 19th Century German journalist, coined the term antisemitism, he was giving a new expression to a very old hatred. Antisemitism, the hatred of Jews and Judaism, has roots of ancient origin, pre-dating the Christian era and evolving throughout the Middle Ages into the modern era. Throughout their history, Jews have been the victims of a persistent pattern of persecution, culminating finally in the 20th Century in mass murder. The term denoting hatred of the Jews – antisemitism – is spelled here and hereafter unhyphenated and in the lower case. This spelling is more historically and etymologically correct since “Semitic” refers not to a race of people, as Marr and other racists of his time wrongly believed, but to a group of languages which includes Arabic as well as Hebrew. Hence, the oft-used spelling “anti-Semitism” means, literally, a prejudice against Semitic-speaking people, not the hatred of people adhering to the Jewish religion and culture. ANTISEMITISM DURING THE PRE-CHRISTIAN ERA Expressions of anti-Jewish prejudice appeared as early as the 4th Century B.C.E. in Greece and Egypt, whose people drew stark distinction between themselves and others, whom they regarded as “strangers,” “foreigners,” or “barbarians.” Jewish religious practice, based as it was on an uncompromising monotheism and strict adherence to their religious laws and social customs, only heightened endemic suspicions and excited hostility in societies already prone to ethnocentric excess. -

John 19: the Crucifixion of Jesus

John 19: The Crucifixion of Jesus TEACHER RESOURCE hen Pilate took Jesus and had him bench in the place called Stone Pavement, in Tscourged. And the soldiers wove a crown Hebrew, Gabbatha. It was preparation day for out of thorns and placed it on his head, and Passover, and it was about noon. And he said clothed him in a purple cloak, and they came to the Jews, “Behold, your king!” They cried to him and said, “Hail, King of the Jews!” out, “Take him away, take him away! Crucify And they struck him repeatedly. Once more him!” Pilate said to them, “Shall I crucify your Pilate went out and said to them, “Look, I king?” The chief priests answered, “We have am bringing him out to you, so that you may no king but Caesar.” Then he handed him over know that I find no guilt in him.” So Jesus to them to be crucified. came out, wearing the crown of thorns So they took Jesus, and carrying the cross and the purple cloak. And he said to them, himself he went out to what is called the “Behold, the man!” When the chief priests and Place of the Skull, in Hebrew, Golgotha. There the guards saw him they cried out, “Crucify they crucified him, and with him two others, him, crucify him!” Pilate said to them, “Take one on either side, with Jesus in the middle. him yourselves and crucify him. I find no guilt Pilate also had an inscription written and put in him.” The Jews answered, “We have a law, on the cross. -

The Death and Resurrection of Jesus the Final Three Chapters Of

Matthew 26-28: The Death and Resurrection of Jesus The final three chapters of Matthew’s gospel follow Mark’s lead in telling of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. At each stage Matthew adds to Mark’s story material that addresses concerns of his community. The overall story will be familiar to most readers. We shall focus on the features that are distinctive of Matthew’s version, while keeping the historical situation of Jesus’ condemnation in view. Last Supper, Gethsemane, Arrest and Trial (26:1–75) The story of Jesus’ last day begins with the plot of the priestly leadership to do away with Jesus (26:1–5). As in Mark 14:1-2 they are portrayed as acting with caution, fearing that an execution on the feast of Passover would upset the people (v 5). Like other early Christians, Matthew held the priestly leadership responsible for Jesus’ death and makes a special effort to show that Pilate was a reluctant participant. Matthew’s apologetic concerns probably color this aspect of the narrative. While there was close collaboration between the Jewish priestly elite and the officials of the empire like Pilate, the punishment meted out to Jesus was a distinctly Roman one. His activity, particularly in the Temple when he arrived in Jerusalem, however he understood it, was no doubt perceived as a threat to the political order and it was for such seditious activity that he was executed. Mark (14:3–9) and John (12:1–8) as well as Matthew (26:6–13) report a dramatic story of the anointing of Jesus by a repentant sinful woman, which Jesus interprets as a preparation for his burial (v. -

Teaching the Scriptural Emphasis on the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2019 Teaching the Scriptural Emphasis on the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ John Hilton III Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hilton, John III, "Teaching the Scriptural Emphasis on the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ" (2019). Faculty Publications. 3255. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/3255 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This article was provided courtesy of the Religious Educator, a journal published by the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University Click here to subscribe and learn more The scriptures consistently emphasize the importance of the Savior’s CrucifixionintheAtonement. theimportance consistentlyemphasize The scriptures oftheSavior’s Harry Anderson, The Crucifixion. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Teaching the Scriptural Emphasis on the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ john hilton iii John Hilton III ([email protected]) is an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University. colleague recently shared with me how, when teaching missionary A preparation classes, he would role-play with students. When students pretending to be missionaries would ask him (acting as an investigator) if he knew about Christ’s Atonement, he would say, “Yes, I saw that Mel Gibson movie about Christ dying for our sins on the cross.” At least half of his students would correct him, stating that Christ atoned for our sins in Gethsemane, but not on the cross. -

Resources This Document Is Intended to Serve As a Resource to White People and Parents to Deepen Our Anti-Racism Work

Anti-racism resources This document is intended to serve as a resource to white people and parents to deepen our anti-racism work. If you haven’t engaged in anti-racism work in the past, start now. Feel free to circulate this document on social media and with your friends, family, and colleagues. Here is a shorter link: bit.ly/ANTIRACISMRESOURCES To take immediate action to fight for Breonna Taylor, please visit FightForBreonna.org. Resources for white parents to raise anti-racist children: ● Books: ○ Coretta Scott King Book Award Winners: books for children and young adults ○ 31 Children's books to support conversations on race, racism and resistance ● Podcasts: ○ Parenting Forward podcast episode ‘Five Pandemic Parenting Lessons with Cindy Wang Brandt’ ○ Fare of the Free Child podcast ○ Integrated Schools podcast episode “Raising White Kids with Jennifer Harvey” ● Articles: ○ How White Parents Can Talk To Their Kids About Race | NPR ○ Teaching Your Child About Black History Month | PBS ○ Your Kids Aren't Too Young to Talk About Race: Resource Roundup from Pretty Good ● The Conscious Kid: follow them on Instagram and consider signing up for their Patreon Articles to read: ● “America’s Racial Contract Is Killing Us” by Adam Serwer | Atlantic (May 8, 2020) ● Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement (Mentoring a New Generation of Activists ● ”My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant” by Jose Antonio Vargas | NYT Mag (June 22, 2011) ● The 1619 Project (all the articles) | The New York Times Magazine ● The Combahee River Collective Statement ● “The Intersectionality Wars” by Jane Coaston | Vox (May 28, 2019) ● Tips for Creating Effective White Caucus Groups developed by Craig Elliott PhD ● “Where do I donate? Why is the uprising violent? Should I go protest?” by Courtney Martin (June 1, 2020) ● ”White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” by Knapsack Peggy McIntosh ● “Who Gets to Be Afraid in America?” by Dr. -

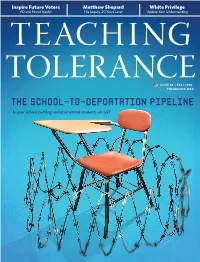

The School-To-Deportation Pipeline Is Your School Putting Undocumented Students at Risk?

Inspire Future Voters Matthew Shepard White Privilege PD and Poster Inside! His Legacy, Years Later Update Your Understanding TEACHING ISSUE | FALL TOLERANCETOLERANCE.ORG The School-to-Deportation Pipeline Is your school putting undocumented students at risk? TT60 Cover.indd 1 8/22/18 1:25 PM FREE WHAT CAN TOLERANCE. ORG DO FOR YOU? LEARNING PLANS GRADES K-12 EDUCATING FOR A DIVERSE DEMOCRACY Discover and develop world-class materials with a community of educators committed to diversity, equity and justice. You can now build and customize a FREE learning plan based on any Teaching Tolerance article! TEACH THIS Choose an article. Choose an essential question, tasks and strategies. Name, save and print your plan. Teach original TT content! TT60 TOC Editorial.indd 2 8/21/18 2:27 PM BRING SOCIAL JUSTICE WHAT CAN TOLERANCE. ORG DO FOR YOU? TO YOUR CLASSROOM. TRY OUR FILM KITS SELMA: THE BRIDGE TO THE BALLOT The true story of the students and teachers who fought to secure voting rights for African Americans in the South. Grades 6-12 Gerda Weissmann was 15 when the Nazis came for her. ONE SURVIVOR ey took all but her life. REMEMBERS Gerda Weissmann Klein’s account of surviving the ACADEMY AWARD® Holocaust encourages WINNER BEST DOCUMENTARY SHORT SUBJECT thoughtful classroom discussion about a A film by Kary Antholis l CO-PRODUCED BY THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM AND HOME BOX OFFICE di cult-to-teach topic. Grades 6-12 THE STORY of CÉSAR CHÁVEZ and a GREAT MOVEMENT for SOCIAL JUSTICE VIVA LA CAUSA MEETS CONTENT STANDARDS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES AND LANGUAGE VIVA LA CAUSA ARTS, GRADES 7-12. -

VII. Interactions with the World C. Anti-Catholicism A. the Know-Nothing Era 391

VII. Interactions with the World C. Anti-Catholicism a. The Know-Nothing Era 391. Editorial, The Catholic Telegraph and Advocate, April 9, 1853 (1) The Late Election. On Monday last an election for municipal officers took place in this city, which resulted in the success of the Democratic-convention nominations, with only a few exceptions. Not only throughout the State of Ohio has the excitement attending this election been known, but papers at the most distant points of the country, have indulged on commentaries in no way complimentary to the Catholics. Now be it known to all to whom these presents shall come, that all the Catholics did was to petition the legislature to amend the school laws, so that Catholic children could attend the schools without sacrifice of the rights of conscience!! This was all our guilt, and we have been repaid by such a deluge of Protestant abuse, misrepresentations and calumny, that we firmly believe the like was never known before in the United States. Editors, preachers, fanatics, loafers, panacea vendors, and quack doctors kept up an assault of such a universal character, that all sorts of style were used at once, all sorts of filth projected against us, all sorts of lies invented, all sorts of insults heaped upon our heads, until it seemed as if the Devil himself was for once exhausted and malignity could do no more. The election day came and the authors of all this insane bigotry and abuse were swept like dust before the power of he people. 392. Editorial, The Catholic Telegraph and Advocate, April 9, 1853 (2) The Source of It. -

The Peformative Grotesquerie of the Crucifixion of Jesus

THE GROTESQUE CROSS: THE PERFORMATIVE GROTESQUERIE OF THE CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS Hephzibah Darshni Dutt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Charles Kanwischer Graduate Faculty Representative Eileen Cherry Chandler Marcus Sherrell © 2015 Hephzibah Dutt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In this study I argue that the crucifixion of Jesus is a performative event and this event is an exemplar of the Grotesque. To this end, I first conduct a dramatistic analysis of the crucifixion of Jesus, working to explicate its performativity. Viewing this performative event through the lens of the Grotesque, I then discuss its various grotesqueries, to propose the concept of the Grotesque Cross. As such, the term “Grotesque Cross” functions as shorthand for the performative event of the crucifixion of Jesus, as it is characterized by various aspects of the Grotesque. I develop the concept of the Grotesque Cross thematically through focused studies of representations of the crucifixion: the film, Jesus of Montreal (Arcand, 1989), Philip Turner’s play, Christ in the Concrete City, and an autoethnographic examination of Cross-wearing as performance. I examine each representation through the lens of the Grotesque to define various facets of the Grotesque Cross. iv For Drs. Chetty and Rukhsana Dutt, beloved holy monsters & Hannah, Abhishek, and Esther, my fellow aliens v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in instructing catechumens, wrote, “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. -

Sermon Series on Exodus

Dr. Rodney Ashlock Chair, Department of Bible, Missions and MInistry Abilene Christian University [email protected] Preaching from the Book of Exodus Exodus in Outline From a preaching perspective it might be helpful to divide the book into two parts: Exodus 1:1-19:1—From Egypt to Sinai Exodus 19:2-40:38—Encamped at Sinai Narrative action dominates the first section of the book with such memorable scenes as Moses and the burning bush, the plagues and the crossing of the Sea moving the action forward at break-neck speed. Israel begins in Egypt but will wind up at the foot of the mountain of God at the beginning of chapter 19. In between Egypt and the Mountain lies the wilderness. Israel will encounter the desert and the challenges it brings. Can Israel learn to trust God even in the dire conditions of the desert? The second section of the book takes on a completely different tenor and pace as the people of Israel settle in for a long stay (roughly a year) in the wilderness of Sinai and at the foot of the mountain. Hear both preacher and the congregation will encounter meticulous instructions and laws pertaining to life with a Holy God and with each other. Highlighting this section are such important pieces of scripture as the Ten Commandments (Ex. 20), instructions for (25-31) and the completion of the Tabernacle and Priestly garments (35-40) and the story of the Golden Calf (32). As preachers of the word of God we will want to pay attention to the shifts in scenery and the different types of genres in these sections. -

Gospel Chronologies, the Scene at the Temple, and the Crucifixion of Jesus

Gospel Chronologies, the Scene at the Temple, and the Crucifixion of Jesus Paula Fredriksen Department of Religion, Boston University (forthcoming in the Catholic Biblical Quarterly) I. The Death of Jesus and the Scene at the Temple The single most solid fact we have about Jesus’ life is his death. Jesus was crucified. Thus Paul, the gospels, Josephus, Tacitus: the evidence does not get any better than this.1 This fact, seemingly simple, implies several others. If Jesus died on a cross, then he died by Rome’s hand, and within a context where Rome was concerned about sedition. But against this fact of Jesus’ crucifixion stands another, equally incontestable fact: although Jesus was executed as a rebel, none of his immediate followers was. We know from Paul’s letters that they survived. He lists them as witnesses to the Resurrection (1 Cor 15:3-5), and he describes his later dealings with some (Galatians 1-2). Stories in the gospels and in Acts confirm this information from Paul. Good news, bad news. The good news is that we have two firm facts. The bad news is that they pull in different directions, with maximum torque concentrated precisely at Jesus’ solo crucifixion. Rome (as any empire) was famously intolerant of sedition. Josephus provides extensive accounts of other popular Jewish charismatic figures to either side of Jesus’ lifetime: they were cut down, together with their followers.2 If Pilate had seriously thought that Jesus were politically dangerous in the way that crucifixion implies, more than Jesus would have died;3 and certainly the community of Jesus’ followers would not have been able to set up in Jerusalem, evidently unmolested by Rome for the six years or so that Pilate remained in office.