Baripada Mudhi a Case Study of Unnayan's Intervention at Tambakhuri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAYURBHANJ C.E Period of Validity Sl

CLINICAL ESTABLISHMENTS IN MAYURBHANJ C.E Period of Validity Sl. Name of the Clinical Name of the Bed District Name of the I/C Doctor Regd. No. Establishment Proprietor Strength No. From To Dr. Durga Nursing Home, Dr. S.S.Khandelwal, 1 Mayurbhanj S.S.Khandelw 097/01 50 23-05-2013 22-05-2015 Baripada, Mayurbhanj MBBS al Orissa Nursing Home & Dr. Arun Ku. Dr. Arun Ku. 2 Mayurbhanj 151/01 5 23-05-2012 22-05-2014 Research Centre, Baripada Goswami Goswami,MBBS Dr. Salim's Nursing Home, Dr. Ghazala 3 Mayurbhanj Dr. Ghazala Salim 153/01 8 01-03-2003 28-02-2005 Karanjia, Salim Laxmikanta Sai X-Ray & Pathology, Pati, Dr. Prafulla Kumar 4 Mayurbhanj 157/02 06-08-2004 05-08-2006 Baripada Samerendra Kar Pati Smt. Jeevan Jyoti Hospital, G.B. Dr. Pradip Ch. 5 Mayurbhanj Chinmayee 311/04 01-03-2004 28-02-2006 Nagar Block Mahanta Satpathy Sarathi Nursing Home, At:- Capt.Partha 6 Mayurbhanj Dr. Kasinath Bisoi,MS 430/05 9 24-05-2013 23-05-2015 Shankhapata, Baripada Sarathi Jena Jaya Pathology, Hospital Sukanta Ku. Dr. R.K.Sahoo, 7 Mayurbhanj 449/05 09-09-2014 08-09-2016 Square, Ward No:-4,Baripada Dash M.B.B.S City Clinic, Hospital Square, Dr. Malaya 8 Mayurbhanj Dr. Malaya Ku. Panda 462/05 16-11-2005 15-11-2007 Baripada Ku. Panda Health Care Pathology Dr. Ramesh Dr. Ramesh Chandra 9 Laboratory & Clinic, Ganesh Mayurbhanj Chandra 511/06 15-04-2013 14-04-2015 Panigrahi,MD-Patho Market, Ward-6, Baripada Panigrahi Gayatri Nursing Hospital & Sri Gadadhar Dr. -

NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA a Progressive Journey Since 2014 Mayurbhanj Parliamentary Constituency

Shri Narendra Modi Hon'ble Prime Minister NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA A progressive journey since 2014 Mayurbhanj Parliamentary Constituency MAYURBHANJ RAILWAYS’ DEVELOPMENT IN ODISHA (2014-PRESENT) MAYURBHANJ PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY A. ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS : Jashipur, Saraskana, Rairangpur, Bangriposi, Udala, Baripada, Morada RAILWAY STATIONS COVERED : Basta, Betnoti, Baripada, N Mayurbhanj Road, Jugpura, Krishna Ch Pura, Thakurtota, Jogal, Badampahar, Kuldiha, Bahalda Road, Aunlajori Junction, Rairanghpur, Gorumahisani, Bangriposi B. WORKS COMPLETED IN LAST FOUR YEARS : B.1. New Lines & Electrication : 90 Kms gauge conversion from Rupsa to Bangriposi at a cost of `183.980 Crore B.2. Improvement of Passenger Amenities Like : Provision of Hand Pump, Benches, Urinals, Latrines, Tube Light with Fittings, LED Fittings, Ceiling Fan, Time Table Display Board at Aunlajori, Chhanua, Birmitrapur, Krishnachandrapur, Jamsole, Baripada, Kuchai, Buramara, Rajaluka, Bangriposi, Bhanjapur Stations at a cost of ` 0.204 Crore. Provision of V.I.P. room and other allied works at Baripada Station at a cost of ` 0.290 Crore. Provision of precast CC grill boundary wall at Betnoti at a cost of ` 0.085 Crore. B.3. Trafc Facilities : Limited Height Subway at LC No. TB66 at a cost of ` 0.950 Crore. B.4. Additional Facilities : Chhanua-Badampahar- Manning of unmanned LC no. TB - 68 73 at Km 33014 - 3311 33509 - 10 at a cost of ` 0.860 Crore. Rairangpur - Development of station as Adarsh Station at a cost of ` 1.060 Crore. Provision of 04 nos hand pump at a cost of ` 0.030 Crore. C. ON-GOING WORKS : C.1. Improvement of Passenger Amenities : Provision of interlocking precast CC blocks at Baripada at a cost of ` 0.080 Crore. -

Full Swing and It Is AVOID FRIED ITEMS Raining Continuously

JULY 26 - AUGUST 1, 2020 HERE . NOW P 3,4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 SUNDAY POST JULY 26 - AUGUST 1, 2020 MIXED BAG Author of The Perfect Flaw, and Butchers of Malevolence, young writer Sailesh Mishra loves conducting literary meet known as Soul Sundays with his fellow writer With family friends where they discuss different concepts. Chef at home Most recently, I Family have taken a jab at cooking. Time Now I help my Spending time family prepare with family dishes and I makes my make some of Sunday special. I my own as well. Early riser feel it is I enjoy being a something which Be it a holiday or chef and needs to be any working day, serving new encouraged. I make sure to dishes to my wake up by 6 am. loved ones. Earlier, I used to wake up at 4 am and go on walks with my father Avid Meeting and see the reader writer sunrise. Without reading friends and writing, Fitness Sundays sound I meet my fellow freak boring for me. writer friends Therefore, I and discuss I enjoy workout prefer to clear literature on a sessions on my the backlog of forum which we terrace on my Kindle Sunday evenings. account. I also have named Soul No matter write a lot on Sundays. whether it is a Sundays. hectic day or a lazy Sunday, I never miss my exercises. I often go on long walks on Sunday RASHMI REKHA DAS, OP evenings. DISTURBING TREND DELAYED RECOGNITION LETTERS Sir, I liked the cover story Survival Tales published Sir, I found the interview of actor, director and last week in your Sunday supplement. -

OFFICE of the DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER CUM DMU CHIEF, KARANJIA At/Po-Karanjia, Dist-Mayurbhanj, Pin-757037

OFFICE OF THE DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER CUM DMU CHIEF, KARANJIA At/Po-Karanjia, Dist-Mayurbhanj, Pin-757037 CONTRACTUAL ENGAGEMENT of FMU COORDINATOR FOR ODISHA FORESTRY SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT-II Divisional Forest Officer cum DMU Chief, Karanjia invites application from suitable candidates for the following positionsat various FMUs (Forest Ranges) under Karanjia Forest Division for working in the Odisha Forestry Sector Development Project, Phase-II: Division Name of the FMUs Name of the Post Vacancy Karanjia 1. Dudhiani FMU Coordinator (Micro Forest 2. Gueguria Planning and Livelihood 05 Division 3. Karanjia Support) 4. Kendumindi FMU Coordinator 5. Thakurmunda (Training & Process 05 Documentation) Interested candidates may obtain Terms of Reference and the Application Form from O/o the Divisional Forest Officer cum DMU Chief, Karanjia during office hours or may download from the website i.e. www.ofsdp.org. Filled in application complete in all respect along withBank Draft for Rs.500/- in favour of Divisional Forest Officer, Karanjia should reach the O/o the Divisional Forest Officer cum DMU Chief, Karanjia on or before 4.00 PM on 12.10.2017 Divisional Forest Officer-cum-DMU Chief Karanjia Project brief & Vacancy details: ODISHA FORESTRY SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT - PHASE-II is being implemented with the loan assistance from Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 10 districts of Odisha. This project is for a period of 10 years from 2017-18 to 2026-27. The project objective is to enhance forest ecosystem along with sustainable livelihood of local people by improving sustainable forest management, sustainable biodiversity conservation and community development, thereby contributing to harmonization between environmental conservation and socio-economic development in the Project area in Odisha. -

Interstate Routes in Between Odisha and Jharkhand

.,-. AIFEE LIST OF VACANT -INTERSTATE •ROUTES IN BETWEEN ODISH A AND JHARKHAND No., . Permits to No. of SI Distance of the Route in KMs Name of the routes be issued Trips Nature of No. J . by Service Jharkh W. Total Length Odisha Bihar Odisha Odisha and Bengal of the Route 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ,Bhadrak to Tata via.Balasore, 1 255 Baripada, Rairangpur, Tiring 40 0 0 295 1 1 Express Baripada to Chakulia 2 41 via.Jamsola 39 0 0 80 2 ' 4 Ordinary _ Bolani to Chaibasa via.Barbil, 3 40 Nalda, Badajamda 107 0 0 147 1 2 Ordinary Baripada to Bokaro 4 via.Rairangpur, Tiring, Tata, 118 166 0 64 348 2 2 -Express Purulia . Baripada to Musabani 5 40 via.Jamsola 45 0 0 85 3 6 Ordinary - . Chaibasa to Rairangpur 6 45 via.Tiring, Hata 120 0 . 0 165 1 • 2 Ordinary Chaibasa to Barbil via.Cha mpua, 7 65 Jayantgarh 67 0 0 132 1 2 Ordinary . Deoghar to Baripada via.Giridih, 8 Hazaribag, Ranchi, Tata, 118 500 0 0 618 2 2 •ExpFess . Rairangpur, Tiring • • 9 Gumla to Baripada via.Sisai, 118 270 0 Ranchi, Tata, Tiring, RaWangpur 388 2 2 express 10 Jharadihi to Saraikela via.Tata, Tiring 95 0 135 1 2 Ordinary Ranchi to Keonjhar via.Khunti, 11 195 0 0 Chaibasa, Champua 249 2 2 Ordinary Rourkela to Gua via.Barbil, 12 Nalda 20 0 0 194 1 2 Ordinary Simdega to Sundergarh 13 via.Subdega, Rouldega, 88 60 0 0 148 Sagbahal 1 2 Ordinary Simdega to Debgarh 14 via.Birmitrapur, Rourkela, 190 48 0 0 238 Panposh, Bonai, Barkot 1 1 Ordinary 15 Joda to Gumla via.Lasthikata, 175 130 0 0 Rourkela, Biramitrapur 305 1 1 .Express Baripada to Chatra via.Jamsola, 16 40 355 0 0 Tata, Ranchi 39'5 1 1 Express Baripada ato Daltanganj 17 via.Rairangpur, Tiring, Tata, 118 395 0 0 513 Ranchi 1 1 Express Berhampur to Tata via.Baripai 18 da, Jamsola renamed 483 235 0 0 as Berhampur to Ranchi 718 1 1 Expr-ess via.Jamsola, Tata • LIST OF VACANT INTERSTATE ROUTES PLYING BETWEEN ODISHA AND BIHAR PASSING THROUGH JHARKHAND THE . -

OFDC Citizen Charter-I.Pdf

ORISSA FOREST DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD (A Government of Orissa Undertaking) A/84,Kharvel Nagar,Bhubaneswar-751001 FAX:0674-2535934 , PABX:0674-2534086/2534269 [website: www.orissafdc.com E-mail ID: [email protected]] OFDC ‐ IT'S INCORPORATION; CORPORATE STATUS & OFFICES Orissa Forest Corporation was established in 1962 as a Marketing Agency of State Forest Department with a view to eliminate over lapping of forestry activities. The State Government decided to merge all the three forest based Corporations of the state with effect from 01/10/1990 by execution of necessary agreement for sale under the Companies Act. Accordingly the activities of SFDC and OFDC were merged with O.F.C. in consideration of the development. After sale of the transferred and transferee corporations, the OFC was renamed as “ORISSA FOREST DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED” (OFDC) with effect from 14/11/1990. Latter on O.C.B. was merged with OFDC with effect from 01/04/1991 in pursuance of the agreement for sale. OF DC is a Public Sector Undertaking. It is an MoU signing Company with the Government of Orissa. 1. Registered Corporate Office at A/84-Kharvel Nagar, Bhubaneswar 2. Four Zone Offices at Berhampur,Bhubaneswar,Bolangir & Sambalpur 3. 21 Division offices in various places of Orissa as mentioned below 1.Angul-CKL 2.Baripada-C 3.Berhampur-C 4.Bhanjanagar-C 5.Bhawanipatna- CKL 6.Bhubaneswar-C 7.Bhubaneswar-Pl 8.Bolangir- CKL 9.Boudh- CKL 10.Deogarh- CKL 11.Dhenkanal- CKL 12.Jajpur Road-C 13.Jeypore- CKL 14.Jharsuguda- CKL 15.Karanjia-C 16.Keonjhar- CKL 17. -

List of Digital Theatres for UFO Movies India Ltd

List of Digital Theatres For UFO Movies India Ltd. S.No. THEATRE_CODE THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS1 CITY ACTIVE PAYEE_CODE DISTRICT STATE COMPANY_NAME CMP_CODE SEATING INS_DATE WEB_CODE Main Road, Tagarapuvalasa, Ganesh 1 TH1177 Vizaq, Pin - 531162, Andhra Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 537 9/26/2011 3235 (Tagarapuvalasa) Pradesh Bowdava Road, Vizag, Pin - 2 TH1178 Gokul Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 515 9/26/2011 3244 530004, Andhra Pradesh Main Road, Parvathipuram, Sri Veerabhadra 3 TH1180 Dist-Vijayanagaram, Pin Parvathipuram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 396 9/26/2011 3698 Picture Palace Code - 535501 AP Radhamadhav Chipurupalli, 4 TH1181 Theatre Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 517 9/26/2011 3717 Vijayanagaram (Chipurupalli) 5 TH1182 N.C.S. Theatre A/C Vizianagaram, Pin - 535001 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 577 9/26/2011 2696 Sri Vasavi Kala Main Road, Bobbili, 6 TH1183 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 475 9/26/2011 2700 Mandir (Bobbili) Vizianagaram, Sri Ramanaah 7 TH1184 Theatre Devarapalli, West Godavari Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 371 9/26/2011 2689 (Devarapalli) Main Road, Moidha Sri Satya Theatre 8 TH1185 Junction, Nellimarla, Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 258 9/26/2011 2588 (Nellimarla) Vizianagaram, Pin - 535217 LakshmiLakshmi KKrishnarishna 9 TH1186 Janagoan, Warangal, AP Janagoan Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 747 9/26/2011 832 Deluxe Sri Venkateshwara Main Road, Maripeda - 10 TH1187 Maripeda Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 459 9/26/2011 2653 Theatre 506315, Dist Warangal Main RoadRoad,, MariMaripeda,peda, Dist.-Dist. -

INTEGRATED TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY: KARANJIA E-Mail: [email protected] No.___154______/ITDA(KJA) Dated 11/02/2020 Tender Call Notice

INTEGRATED TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY: KARANJIA e-mail: [email protected] No.___154________/ITDA(KJA) Dated 11/02/2020 Tender Call Notice Sealed Tenders in plain paper are invited from the intending reputed registered Firms/ Suppliers ( having branded company authorization/ branded company authorized dealers may be preferred subject to favourable cost and quality) for supply of different category of items such as “ ((i) Water Purifier with R.O. System (ii) Inverter with Battery (iii) Sanitary Incinerator (iv) Mattress (v) Washing Machine to be supplied to the SSD Hostels/Schools in Panchpir Sub-Division as decided by the Sub-Divisional Level Purchase Committee for the current Financial Year 2019-20 . Categorically Items wise specification is mentioned as follows. The bidder has to super scribe on the Envelop for which item or category of items, he/she intends to participate in the tender. TENDER DOCUMENTS IMPORTANT INFORMATION TO THE BIDDERS. 1 Availability of Tender www.mayurbhnaj.nic.in 2 Date and Time for submission of the Tender Last date 26.02.2020 upto 2.00 documents by Speed Post/ Registered post P.M. only. 3 Earnest Money deposit (Refundable ) EMD Rs…………..….. (Rupees ……………….…….) only separate for each category of items as mentioned below will be deposited. 4 Non refundable paper cost Separate for each category of items as mentioned below. 5 (i) Technical Bid Duly filled in and to be opened at 03.30 P.M. on 26.02.2020 (ii) Financial Bids of eligible Tenderer Financial Bids of the bidders will be opened of those who would qualify in Technical bid. In financial bid sample is must along with quoted price. -

DIRECTORY of OFFICERS - ODISHA Principal CCIT Odisha Region Sl

DIRECTORY OF OFFICERS - ODISHA Principal CCIT Odisha Region Sl. Name of the Officer Designation Office Address Contact Details Mobile No. No. O/o THE AAYAKAR Santosh Kumar 0674- 2589119 / 1 Pr. CCIT BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 9438917000 Srivastava 2589125(Fax) BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR Addl.CIT(Hqrs.) 0674-2589119 / 2 Sarat Kumar Dash BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 9438917255 (Admn) 2589125(Fax) BHUBANESWRA - 751007 Addl.CIT(Hqrs.) O/o THE AAYAKAR 0674-2589299 / 3 Sarat Kumar Dash (Tech), BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 2589119 / 9438917255 (Addl.Charge) BHUBANESWRA - 751007 2589118(Fax) O/o THE AAYAKAR Addl.CIT(Hqrs.) 0674-2589466(T) / 4 Sarat Kumar Dash BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 9438917255 (Vig),(Addl.Charge) 2589263(F) BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR DCIT(Hqrs)(Admn) 5 Lal Mohan Majhi BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 0674-2589733(T/F) 9438917532 (Vig.) BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR Abhaya Charan 6 DCIT(PR&Wel) BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 0674-2589733 9438917532 Rout BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR 7 Smt. Pranati Mishra ACIT(OSD) BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 0674-2589441(T/F) 9438917528 BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR Pradeep Kumar 8 ITO(Judl. & Tech) BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 0674- 2589305 9438917230 Singh BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR 9 K.C. Barik ITO(OSD) &HoO BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 0674- 2589529 9438917440 BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o THE AAYAKAR 0674- 2589380 / 10 Kalpataru Mishra ITO(Legal Cell) BHAWAN,RAJSWA VIHAR, 9438917131 2589920(F) BHUBANESWRA - 751007 O/o the COMMISSIONER OF 0674- 2589442(D)/ 11 P.K. Dash CIT (Addl.Charge) INCOME-TAX, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 2589923/ 9438917011 BHUBANESWAR-751007 2589278(Fax) O/o the COMMISSIONER OF 12 J K Lenka DCIT(Hqrs) INCOME-TAX, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 0674- 2589237(T/F) 9438917069 BHUBANESWAR-751007 O/o the COMMISSIONER OF 13 Ananda Ku. -

Ratha Yatra of Baripada - Unique in Many Ways

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review aripada, the headquarters of Mayurbhanj Abdhi (4) and Subhransu (1) or 1497 Bdistrict bears the testimony of many corresponding to I575 A.D. magnificent monument of immense religious significance under the patronage of the illustrious Legend has it that Maharaja Baidyanath Bhanja rulers. Apart from Puri, Lord Jagannath, Bhanja had gone to Puri to have a darshan of worshipped as Shri Haribaldev Mahaprabhu at Lord Jagannath but was denied entry into Puri, Baripada is the second biggest one in Odisha and for he failed to offer the demanded gold coins for is acclaimed as the Second Shreekshetra of the purpose. Another version to the legend goes Odisha. like this .When Maharaja Baidyanath Bhanj went to Puri in royal splendour with the accompaniment The temple of Lord Jagannath at Baripada, of chhatro and chamara, the Gajapati made of laterite stone with exquisite designs Maharaja of Puri refused permission as it was engraved in the walls, has height of 84'-6". A brick display of higher status over the Thakur Raja of boundary wall encircles the temple which is a Puri. The prevailing custom then was that the Ratha Yatra of Baripada - Unique in Many Ways Balabhadra Ghadai replica of that of Lord Jagannath temple at Puri. devotees to Puri would come as common men A small inscription in two lines is found fixed to without showing of any supremacy over the the upper portion of the right hand boundary wall Gajapati who is chalanti Vishnu designate. of the temple indicates the date of construction of The Maharaja went in penance near the Atharanala Bridge , the gateway to Shrikshetra. -

Chapter III Compliance Audit DEPARTMENT of COOPERATION

Chapter III: Compliance Audit Chapter III Compliance Audit Compliance Audit of Departments of Government and their field formation brought out instances of lapses in management of resources and failure in observance of regularity and propriety. These have been discussed in the succeeding paragraphs. DEPARTMENT OF COOPERATION 3.1 Odisha State Agricultural Marketing Board 3.1.1 Introduction Odisha State Agricultural Marketing Board (OSAMB) being an apex statutory body in the State under Cooperation Department was established in 1985 after amendment of Odisha Agriculture Produce Markets (OAPM) Act 1956 in the year 1984 to exercise supervision and control over the working and other affairs of Regulated Market Committees (RMCs). It includes programmes for development of markets and market areas with intention of regulating sale and purchase of agriculture produce in the State. The Board supervises and guides the RMCs in preparation of plan and estimates of construction works undertaken for development of markets and market areas. The objective of this body is to regulate the markets for agriculture produce to ensure payment of fair price to the agriculturists. At present under the control of the Board, 66 RMCs are operating covering 314 Blocks of the State. The above RMCs supervise 483 markets comprising of 54 principal market yards and 429 submarket yards. In addition, 43 krushak bazars were also established. Audit was conducted during April-July 2015 covering the period of five years ending March 2015 in 2017 out of 66 RMCs on the basis of revenue earnings. Audit objectives were to assess whether adequate marketing infrastructure was available and satisfactory mechanism exists to secure fair price for agricultural produce. -

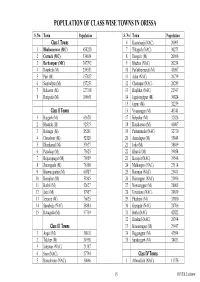

Population of Class Wise Towns in Orissa

POPULATION OF CLASS WISE TOWNS IN ORISSA S. No. Town Population S. No. Town Population Class I Towns 6 Kantabanji (NAC) 20095 1 Bhubaneswar (MC) 658220 7 Titlagarh (NAC) 30273 2 Cuttack (MC) 534654 8 Deogarh (M) 20096 3 Berhampur (MC) 307792 9 Bhuban (NAC) 20234 4 Rourkela (M) 259553 10 Parlakhemundi (M) 43097 5 Puri (M) 157837 11 Aska (NAC) 20739 6 Sambalpur (M) 157253 12 Chatrapur (NAC) 20289 7 Balasore (M) 127358 13 Hinjlikat (NAC) 21347 8 Baripada (M) 100651 14 Jagatsinghpur (M) 30824 15 Jajpur (M) 32239 Class II Towns 16 Vyasanagar (M) 40741 1 Bargarh (M) 63678 17 Belpahar (M) 32826 2 Bhadrak (M) 92515 18 Kendrapara (M) 41407 3 Bolangir (M) 85261 19 Pattamundai (NAC) 32730 4 Choudwar (M) 52528 20 Anandapur (M) 35048 5 Dhenkanal (M) 57677 21 Joda (M) 38689 6 Paradeep (M) 73625 22 Khurda (M) 39054 7 Brajarajnagar (M) 76959 23 Koraput (NAC) 39548 8 Jharsuguda (M) 76100 24 Malkangiri (NAC) 23114 9 Bhawanipatna (M) 60787 25 Karanjia (NAC) 21441 10 Keonjhar (M) 51845 26 Rairangpur (NAC) 21896 11 Barbil (M) 52627 27 Nowrangpur (M) 28005 12 Jatni (M) 57957 28 Umarkote (NAC) 24859 13 Jeypore (M) 76625 29 Phulbani (M) 33890 14 Sunabeda (NAC) 58884 30 Gunupur (NAC) 24706 15 Rayagada (M) 57759 31 Burla (NAC) 42822 32 Hirakud (NAC) 26394 Class III Towns 33 Biramitrapur (M) 29447 1 Angul (M) 38018 34 Rajgangpur (M) 43594 2 Talcher (M) 34998 35 Sundargarh (M) 38421 3 Jaleswar (NAC) 21387 4 Soro (NAC) 27794 Class IV Towns 5 Basudevpur (NAC) 30006 1 Athmallick (NAC) 11376 15 RCUES, Lucknow S.