Thesis-1974D-C324v.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers the Real Wild West Writings

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers The Real Wild West Rev. July 2013 Writings 1:1 Typed draft book proposals, overviews and chapter summaries, prologue, introduction, chronologies, all in several versions. Letter from Wallis to Robert Weil (St. Martin’s Press) in reference to Wallis’s reasons for writing the book. 24 Feb 1990. 1:2 Version 1A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 19p. 1:3 Version 1B, 28p. 1:4 Version 1C, 75p. 1:5 Version 2A, 37p. 1:6 Version 2B, 56p. 1:7 Version 2C, marked as final draft, circa 12 Dec 1990. 56p. 1:8 Version 3A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen. The Story of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Empire…” 55p. 1:9 Version 3B, 46p. 1:10 Version 4: “The Read Wild West. Saturday’s Heroes: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 37p. 1:11 Version 5: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the 101 Ranch.” 8p. 1:12 Version 6A: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the Miller Brothers and the 101 Ranch.” 25p. 1:13 Version 6B, 4p. 1:14 Version 6C, 26p. 1:15 Typed draft list of sidebars and songs, 2p. Another list of proposed titles of sidebars and songs, 6p. 1:16 Introduction, a different version from the one used in Version 1 draft of text, 5p. 1:17 Version 1: “The Hundred and 101. The True Story of the Men and Women Who Created ‘The Real Wild West.’” Early typed draft text with handwritten revisions and notations. Includes title page, Dedication, Epigraph, with text and accompanying portraits and references. -

Thesis-1972D-C289o.Pdf (5.212Mb)

OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVISM, 1901-1917 By GEORGE O. CARNE~ // . Bachelor of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1964 Master of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1965 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1972 OKLAHOMA STATE UNiVERSITY LIBRARY MAY 30 1973 ::.a-:r...... ... ~·· .. , .• ··~.• .. ,..,,.·· ,,.,., OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVIS~, 1901-1917 Thesis Approved: Oean of the Graduate College PREFACE This dissertation is a study for a single state, Oklahoma, and is designed to test the prevailing Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis concerning progressivism. The "progressive profile" as developed in the Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis characterizes the progressive as one who possessed distinctive social, economic, and political qualities that distinguished him from the non-progressive. In 1965 in a political history seminar at Central Missouri State College, Warrensburg, Missouri, I tested the above model by using a single United States House representative from the state of Missouri. When I came to the Oklahoma State University in 1967, I decided to expand my test of this model by examining the thirteen representatives from Oklahoma during the years 1901 through 1917. In testing the thesis for Oklahoma, I investigated the social, economic, and political characteristics of the members whom Oklahoma sent to the United States House of Representatives during those years, and scrutinized the role they played in the formulation of domestic policy. In addition, a geographical analysis of the various Congressional districts suggested the effects the characteristics of the constituents might have on the representatives. -

Thanksgiving-1947 9

• 44". Won In M ,Mrs. Edw, who served .1 ter of the spoke at the ing of the A ANOTHER SUTHERLAND FIRST men Voters Phillips Aral "Women in Mrs. O'Kel dover at the Welfare con of which [Mr man. Mrs. O'Ke laws and cc A HEM are unjust to she cited the mandatory s, victed of col that for mer lieves that without a f facts and tin dealt with i And It's Ready ! manner. Women of prehended f, offenders, wl means receil too often co It's just one, two — up comes the hem and you're ready with the skirt hit of the season. Make it long, Marriage The follow make it short, make it any length you wish, for these riage have '13, the Town Cl tubular all wool jersey skirt lengths come 38" long. George J The elasticized, shirred waist fits it to any size from Haverhill an 382 Andover 24 to 36. In black, grey, red, natural and dubonnet. Henry V. and Priscille Ave., Lynn. Roland J. Jeannette L St., Lawrenc Engageme Ballerina Joseph B street, Meth gagement o Dolores, to Skirt erd, son of and the latE Both are Lengths ward F. Sea uen. Miss C clilfe collegE at the H. Her fiance $395 in the Ar: is now a si versity. Wedding each SI INA—DI Elizabeth ter of Mr. 56 Maple marriage • Silva of Te 16, at St. A ceremony N Rev. M. F. ANDOVER CUSTOMERS - - - Births A daugh Call Andover 300 14, at Law to Mr. and Essex stre€ No Toll Charge former Fra A son Fr Lawrence C and Mrs. -

HISTORY of OKLAHOMA CONGRESSMEN U.S

HISTORY OF OKLAHOMA CONGRESSMEN u.s. Senate - Thomas Pryor Gore (D) elected 1907; J. W. Harreld (R) elected 1920; Elmer Thomas (D) elected 1926; Mike Monroney (D) elected 1950; Henry Bellmon (R) elected 1968; Don Nickles (R) elected 1980. u.S. Senate - Robert L. Owen (D) elected 1907; W. B. Pine (R) elected 1924; ThomasP. Gore (D) elected 1930; Josh Lee (D) elected 1936; E. H. Moore (R) elected 1942; Robert S. Kerr (D) elected 1948 (died 1963); J. Howard Edmondson (D) appointed 1-6-63 to fill office until General Election, 1964; Fred R. Harris (D) elected 1964 (for unexpired 2-year term) elected full term 1966; Dewey F. Bartlett (R) elected 1972; David Boren (D) elected 1978. u.S. Representatives: District 1-Bird S. McGuire (R) elected 1907; James S. Davenport (D) elected 1914; T. A. Chandler (R) elected 1916; E. B. Howard (D) elected 1918; T. A. Chandler (R) elected 1920; E. B. Howard (D) elected 1922; S. J. Montgomery (R) elected 1924; E. B. Howard (D) elected 1926; Charles O'Connor (R) elected 1928; Wesley E. Disney (D) elected 1930; George R. Schwabe (R) elected 1944; Dixie Gilmer (D) elected 1948; George R. Schwabe (R) elected 1950; Page Belcher (R) elected 1952; James R. Jones (D) elected 1972. District 2 - Elmer L. Fulton (D) elected 1907; Dick T. Morgan (R) elected 1908; W. W. Hastings (D) elected 1914; Alice M. Robertson (R) elected 1920; W. W. Hastings (D) elected 1922; Jack Nichols (D) elected 1934 and resigned 1944; W. G. Stigler (D) elected 3-8-44 to fill unexpired term and elected full term 1944; Ed Edmondson (D) elected 1952; Clem Rogers McSpadden (D) elected 1972; Theodore M. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Women's Gymnastics Score Sheet Page: 1 Team: Home University of Illinois Visitor Oklahoma 2010 MEET-BY-MEET RECAPS 1/23/2010 9:30:11PM Champaign, Ill

WOMEN’S GYMNASTICS OKLAHOMAPhillip Rogers, Women’s Gymnastics Communications Live Stats: SoonerSports.com | Blog (OU routines only): SoonerSports.com 180 W. Brooks, Suite 2525, Norman, OK 73019 O: (405) 325-8413 | C: (405) 880-0794 | F: (405) 325-7623 MEET 14 - NO. 2 OKLAHOMA AT NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS [email protected] | www.SoonerSports.com April 22-24 | Steven C. O’Connell Center | Gainesville, Fla. ON THE WEB OU’s home meets can be seen via a live web cast with UCLA BRUINS UTAH UTES OSU BEAVERS (NQS: 394.885, No. 1 Seed) (NQS: 393.385, No. 5 Seed) (NQS: 392.820, No. 8 Seed) commentary from Sooner All-American Kasie Tamayo and Ashley Alden on Oklahoma All-Access, SoonerS- ports.com’s premium site. Live stats for all meets can be found on SoonerSports.com. OKLAHOMA SOONERS (22-0, 6-0 BIG 12) LSU TIGERS NEBRASKA CORNHUSKERS (NQS: 392.815, No. 9 Seed) (NQS: 392.230, No. 12 Seed) 2010 TROESTER RANKINGS TICKETS NQS: 394.420 - No. 4 Seed For home meet tickets, call (405) 325-2424 or toll-free Vault (RQS): 49.415 (First) | Bars (RQS): 49.295 (Second) Beam (RQS): 49.380 (First) | Floor (RQS): 49.355 (Fourth) (800) 456-GoOU. Tickets can also be purchased at the main ticket office in Gaylord Family-Oklahoma Memorial AT A GLANCE: Stadium or at Lloyd Noble Center on the day of the meet. No. 4 seed Oklahoma will compete in the first semifinal session of the NCAA Women’s Gymnastics Championships on April 22 at Noon (CT). The seeds are determined by adding the regional qualifying score (RQS) and score from regional competition to determine a national qualyifing score (NQS). -

Romantic Campus Bench Deserted in the Sunset. Reason: Cooler Inside

Time : July . Temperature : 100 degrees . Situation: romantic campus bench deserted in the sunset . Reason : cooler inside Library or Union. JULY, 1957 PAGE 1 7 a series of brief news stories of events that shaped the lives of the alumni family 1908-20 man, will travel to the Beirut (Lebanon) College of 1931-35 Paul A. Walker, '12Law, recenay moved to Women to teach coeds modern American home- Lieut. Col. William H. Witt, '326a, now is as- Norman from Washington, D. C. Now retired, he making methods during the coming school year. signed as officer in charge of the Pacific Stars and served several years as an Oklahoma official, then Mrs. Snoddy, assistant professor of home economics Stripes, daily newspaper for the U. S. security forces for 20 years as a member of the Federal Communi- at O. U., will do the work through a scholarship in the Far East . Witt formerly worked for the Tul- cations Commission. He was given by one of the original Omicron Nu, national home economics sa World, Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City Times, members of the F. C. C. when it was organized in honor society. She will sail in August . Norman Transcript, Oklahoma News and Colum- 1934 . MARRIAGE : Mrs. Elveta Minteer Hughes, '24, bus (Ohio) Citizen. Also, he served as a contribut- Dr. Roy A. Morter, '13med, Kalamazoo, Michi- Norman, and Albert Marks Lehr, Jr ., Tulsa, were ing editor of Sooner Magazine and as publicity di- gan, received an honorary degree June from married June 7 in Tulsa, 15 where they have made rector of O. -

Roll Call New Orleans, Louisiana

1920 Edna Bessent, '206a, former languages salesman for the company at Dallas, has been teacher in the University, was recently associated with the firm since 1925 . He has awarded a fellowship to study the literature of invented special apparatus and processes used in Uruguay at the University of Montevideo by the the heat treatment of aluminum alloys . Institute of International Education . Miss Bes- FRUIT-CHESNUTT : An event of February 1 sent declined to accept the fellowship because, a in Holdenville was the wedding of Miss Dorothy short time before the grant was announced, she Fruit, Shawnee, to Clyde W. Chestnutt, '22=23, accepted a faculty position at Newcomb College, at the home of the bridegroom's parents. Mrs. Roll Call New Orleans, Louisiana. Chestnutt attended Oklahoma Baptist University, Grover Strother, '206a, Oklahoma City, was Shawnee, and the Leland Powers Schoof of of Sigma Alpha Speech, Boston, Massachusetts . The couple have re-elected province president established a home in Holdenville where Mr. Epsilon fraternity at a meeting held March 6 Chestnutt is associated with his father in the and 7 at Stillwatcr. hardware business . By EDITH WALKER 1921 Gerald Tebbe, '21law, Madill attorney, Mrs. Jeanette Barnes Monnet, '23ba, Oklaho- has been appointed county attorney of ma City, has been re-elected president of the Marshall County to succeed Lt. John A. Living- Y. W. C. A. in Oklahoma City by the board of ston, '376a, '39law, called to active duty. Mr . directors. Her husband, Claude Monnet, '206a, Tebbe served in France during the first World '22law, is an Oklahoma City attorney. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Prohibition, Protests, and Politics the EDMONDSON ADMINISTRATION

Chapter 23 Prohibition, Protests, and Politics THE EDMONDSON ADMINISTRATION. Tulsa attorney J. Howard Ed- mondson was inaugurated as governor in January, 1959. At 33, he was the state’s youngest governor in history. Edmondson’s “prairie fire” and “Big Red E” campaigns (both named for his red hair) brought him from behind to defeat Midwest City builder W.P. “Bill” Atkinson in the Democratic primary. He then de- feated Phil Ferguson in the general election by the largest majority ever given a gubernatorial candi- date in the state. Also in 1959, the youthful governor was named an honorary member of the Oklahoma Hall of Fame. He was honored as one of the nation’s “Ten Most Outstanding Young Men.” Born in Muskogee in September, 1925, Ed- mondson obtained a law degree from the Uni- versity of Oklahoma. He served a stint in the Air Force and was a Tulsa County Attorney before becoming governor. One of Edmondson’s promises was that he would either enforce or repeal prohibition, and he did both. He promised upon taking office that “every Oklahoman who votes dry will drink dry.” He turned Attorney General Joe Cannon loose to enforce prohibition. Raids were made all across the state on bars and nightclubs which were ille- gally serving liquor. The state’s bootleggers became fair game for law enforcement officials who had previously overlooked their violations of the law. Governor J. Howard Perhaps for the first time since statehood, Oklahoma citizens knew Edmondson what it meant to be “dry.” People who were accustomed to having access to liquor despite prohibition and who consequently had never seriously considered the matter, found that true prohibition was more than a little inconvenient. -

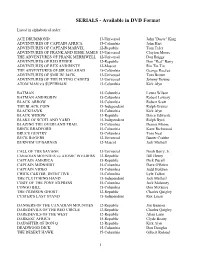

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1941, TO JANUARY 3, 1943 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1941, to January 2, 1942 SECOND SESSION—January 5, 1942, 1 to December 16, 1942 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES 2—JOHN N. GARNER, 3 of Texas; HENRY A. WALLACE, 4 of Iowa PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—PAT HARRISON, 5 of Mississippi; CARTER GLASS, 6 of Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—EDWIN A. HALSEY, of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—CHESLEY W. JURNEY, of Texas SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—SAM RAYBURN, 7 of Texas CLERK OF THE HOUSE—SOUTH TRIMBLE, 8 of Kentucky SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—KENNETH ROMNEY, of Montana DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH J. SINNOTT, of Virginia POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FINIS E. SCOTT ALABAMA ARKANSAS Albert E. Carter, Oakland SENATORS John H. Tolan, Oakland SENATORS John Z. Anderson, San Juan Bautista Hattie W. Caraway, Jonesboro John H. Bankhead II, Jasper Bertrand W. Gearhart, Fresno John E. Miller, 11 Searcy Lister Hill, Montgomery Alfred J. Elliott, Tulare George Lloyd Spencer, 12 Hope Carl Hinshaw, Pasadena REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Jerry Voorhis, San Dimas Frank W. Boykin, Mobile E. C. Gathings, West Memphis Charles Kramer, Los Angeles George M. Grant, Troy Wilbur D. Mills, Kensett Thomas F. Ford, Los Angeles Henry B. Steagall, Ozark Clyde T. Ellis, Bentonville John M. Costello, Hollywood Sam Hobbs, Selma Fadjo Cravens, Fort Smith Leland M. Ford, Santa Monica Joe Starnes, Guntersville David D. Terry, Little Rock Lee E. Geyer, 14 Gardena Pete Jarman, Livingston W. F. Norrell, Monticello Cecil R. King, 15 Los Angeles Walter W.