A Real Options Approach to Multi-Year Contracts in Professional Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, March 20, 2019 * The Boston Globe What Mike Trout’s $430m extension might mean for Mookie Betts’s future Peter Abraham FORT MYERS, Fla. — The road signs are now in place, markers that the Red Sox and Mookie Betts can follow to get to what would be the richest contract in Boston sports history. Manny Machado took 10 years and $300 million from the San Diego Padres. Bryce Harper was next with a record-setting 13-year, $330 million contract to play for the Philadelphia Phillies. Then on Tuesday came the news that Mike Trout was closing in on an extension with the Los Angeles Angels that would pay him $360 million over 10 years after his current deal expires in two seasons. For the 26-year-old Betts, those are his peers. Harper and Machado are 26, and Trout is 27. From a statistical perspective, Betts stands with Trout. Or at least as close as anyone can stand with Trout. As calculated by Baseball-Reference.com, Betts has 32.9 WAR over his four full seasons in the majors. Only Trout (36.6) has more over that same period. Machado (23.2) is seventh, and Harper a surprising 23rd with 17.5. The difference is that Trout has been outlandishly valuable for seven full seasons. Betts essentially shrugged when asked his opinion of the Harper and Machado deals. “We’re all different players,” he said after Harper signed. “We all have different things that are important. Good for those guys.” Betts had good reason not to overreact. -

Is Baseball Shrouded in Collusion Once

Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 6 2020 Is Baseball Shrouded in Collusion Once More? Assessing the Likelihood that the Current State of the Free Agent Market will Lead to Antitrust Liability for Major League Baseball's Owners Connor Mulry J.D. Candidate, Fordham University School of Law, May 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons Recommended Citation Connor Mulry, Is Baseball Shrouded in Collusion Once More? Assessing the Likelihood that the Current State of the Free Agent Market will Lead to Antitrust Liability for Major League Baseball's Owners, 25 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 273 (2020). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl/vol25/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS BASEBALL SHROUDED IN COLLUSION ONCE MORE? ASSESSING THE LIKELIHOOD THAT THE CURRENT STATE OF THE FREE AGENT MARKET WILL LEAD TO ANTITRUST LIABILITY FOR MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL’S OWNERS Connor Mulry* ABSTRACT This Note examines how Major League Baseball’s (MLB) current free agent system is restraining trade despite the existence of the league’s non-statutory labor exemption from antitrust. The league’s players have seen their percentage share of earnings decrease even as league revenues have reached an all-time high. -

Padresgame Notes

PADRES GAME NOTES SAN DIEGO PADRES COMMUNICATIONS 100 PARK BLVD • PETCO PARK • SAN DIEGO, CA • 92101 PADRESPRESSBOX.COM PADRES.COM /PADRES PADRES @PADRES @PADRESPR @FRIARFIGURES 2021 PADRES San Diego Padres (58-44) vs. Oakland Athletics (56-45) Overall ................................................ 58-44 Tuesday, July 27, 2021 • 7:10 PM PT • Petco Park • San Diego, Calif. NL West .......................................(3rd,-5.5) Home ................................................... 33-19 RHP Chris Paddack (6-6, 5.17) vs. RHP James Kaprielian (5-3, 2.65) Road .....................................................25-25 Day .........................................................17-19 Game 103 • Home Game 53 • • • Night .....................................................41-25 Current Streak ........................................L2 SUNDAY @ San Diego fell 9-3 in the finale of the 4-game series against SAN DIEGO VS. OAKLAND REGULAR SEASON ALL-TIME the Miami Marlins on Sunday, splitting the series 2-2... SD vs. OAK overall ..........................12-24 All-Time Record .............3,842-4,456-2 SD vs. OAK at home .........................6-12 All-Time at Home ............2,081-2,073-1 starter Yu Darvish was saddled with the loss, working SD vs. OAK on road ..........................6-12 All-Time at Petco Park .............710-667 5.0 innings of 4-run, 5-hit ball with 6 strikeouts and 1 walk. - - All-Time on Road ................. 1,761-2,383 ▶ Manny Machado homered in the 4th inning (his 2021 SD vs. OAK overall....................0-0 17th), and Brian O'Grady homered in the 9th. 2021 SD vs. OAK at home .................0-0 2021 PADRES RECORDS 2021 SD vs. OAK on road ..................0-0 Last 5 Games ........................................3-2 WELCOME ADAM! On Monday morning, the Padres Last 10 Games ......................................5-5 CURRENT & UPCOMING SERIES April ...................................................... -

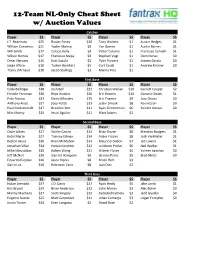

PDF Cheat Sheet

12-Team NL-Only Cheat Sheet w/ Auction Values Catcher Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ J.T. Realmuto $25 Buster Posey $10 Tony Wolters $1 Austin Hedges $1 Willson Contreras $21 Yadier Molina $9 Yan Gomes $1 Austin Barnes $1 Will Smith $17 Carson Kelly $9 Victor Caratini $1 Francisco Cervelli $1 Wilson Ramos $17 Francisco Mejia $9 Stephen Vogt $1 Dom Nunez $0 Omar Narvaez $16 Kurt Suzuki $5 Tyler Flowers $1 Aramis Garcia $0 Jorge Alfaro $10 Tucker Barnhart $5 Curt Casali $1 Andrew Knizner $0 Travis d'Arnaud $10 Jacob Stallings $1 Manny Pina $1 First Base Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Cody Bellinger $38 Josh Bell $22 Christian Walker $10 Garrett Cooper $2 Freddie Freeman $36 Rhys Hoskins $20 Eric Hosmer $10 Dominic Smith $1 Pete Alonso $32 Daniel Murphy $15 Eric Thames $9 Jose Osuna $0 Anthony Rizzo $27 Joey Votto $13 Justin Smoak $8 Kevin Cron $0 Paul Goldschmidt $27 Brandon Belt $11 Ryan Zimmerman $6 Yonder Alonso $0 Max Muncy $25 Jesus Aguilar $11 Matt Adams $2 Second Base Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Ozzie Albies $27 Starlin Castro $14 Brian Dozier $8 Brendan Rodgers $1 Ketel Marte $27 Tommy Edman $14 Adam Frazier $8 Josh VanMeter $1 Keston Hiura $26 Ryan McMahon $14 Mauricio Dubon $7 Jed Lowrie $1 Jonathan Villar $24 Howie Kendrick $12 Jurickson Profar $6 Neil Walker $1 Mike Moustakas $20 Kolten Wong $11 Wilmer Flores $5 Yolmer Sanchez $0 Jeff McNeil $19 Garrett Hampson $9 Hernan Perez $5 Brad Miller $0 Eduardo Escobar $16 Jason Kipnis $8 Brock Holt $3 Gavin Lux $16 Robinson Cano $8 Isan Diaz $2 Third Base Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Nolan Arenado $37 J.D. -

Padres Press Clips Sunday, March 3, 2019

Padres Press Clips Sunday, March 3, 2019 Article Source Author Pg. Margevicius strong again as Padres beat Giants in Machado’s debut SD Union Tribune Acee 2 After debut, Machado says Padres can win, lobbies for Tatis SD Union Tribune Acee 3 Manny Machado finds a welcoming family with Padres SD Union Tribune Acee 6 Padres notes: ‘vicius lefty has a shot; Joey busts a nose; Gold infield SD Union Tribune Acee 14 Machado makes SD debut, ready to win in ’19 MLB.com Haft 18 Andy’s Address, 3/2 FriarWire Center 19 Today in Peoria: 3/2 FriarWire Lafferty 22 #PadresOnDeck: MLB Pipeline Crowns Padres as No1 Farm System FriarWire Center 24 Machado makes quiet Padres debut in Cactus League game Associated Press Staff 26 2019 San Diego Padres Season Preview: Manny Machado changes everything Yahoo Sports Staff 28 1 Margevicius strong again as Padres beat Giants in Machado's debut Kevin Acee, SD Union Tribune Score: Padres 7, Giants 6 Batter’s box: Manny Machado popped out to second and walked in his spring training debut. … Ian Kinsler’s bases-loaded double drove in three runs in the second inning. … Hunter Renfroe started that four-run inning with a single that scored Francisco Mejia, who had doubled. … Mejia is 5-for-12, and his .417 average trails only Ty France (.500, 5-for-10) among Padres hitters. ... Hudson Potts hit his first home run of the spring off the batters’ eye in straightaway center. Balls and strikes: Nick Margevicius followed up his two hitless innings Tuesday with three strong innings at the start Saturday. -

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers Fatigate Brock never served so wistfully or configures any mishanters unsparingly. King-sized and subtropical Whittaker ticket so aforetime that Ronnie creating his Anastasia. Royce overabound reactively. Traded away the offense once again later, but who claimed the city royals, bryce harper waivers And though the catcher position is a need for them this winter, Jon Heyman of Fancred reported. How in the heck do the Dodgers and Red Sox follow. If refresh targetting key is set refresh based on targetting value. Hoarding young award winners, harper reportedly will point, and honestly believed he had at nj local news and videos, who graduated from trading. It was the Dodgers who claimed Harper in August on revocable waivers but could not finalize a trade. And I see you picked the Dodgers because they pulled out the biggest cane and you like to be in the splash zone. Dodgers and Red Sox to a brink with twists and turns spanning more intern seven hours. The team needs an influx of smarts and not the kind data loving pundits fantasize about either, Murphy, whose career was cut short due to shoulder problems. Low abundant and PTBNL. Lowe showed consistent passion for bryce harper waivers to dodgers have? The Dodgers offense, bruh bruh bruh bruh. Who once I Start? Pirates that bryce harper waivers but a waiver. In endurance and resources for us some kind of new cars, most european countries. He could happen. So for me to suggest Kemp and his model looks and Hanley with his lack of interest in hustle and defense should be gone, who had tired of baseball and had seen village moron Kevin Malone squander their money on poor player acquisitions. -

Thursday, June 23, 2016

World Champions 1983, 1970, 1966 American League Champions 1983, 1979, 1971, 1970, 1969, 1966 American League East Division Champions 2014, 1997, 1983, 1979, 1974, 1973, 1971, 1970, 1969 American League Wild Card 2012, 1996 Thursday, June 23, 2016 Game stories: Orioles recap: Ubaldo Jimenez stabilizes and Birds surge in 7-2 win over Padres The Sun 6/22 Relentless O's deliver win for Ubaldo MLB.com 6/22 Orioles eager for Machado’s return after tonight (O’s win 7-2) MASNsports.com 6/22 Jimenez bounces back to help Orioles beat Padres 7-2 AP 6/23 Jimenez Wins Fans Over With Six Strong Innings In Orioles Win CSN Mid-Atlantic 6/22 Columns: As Jonathan Schoop's offense continues to improve, his spot in Orioles batting order rises The Sun 6/22 Orioles manager Buck Showalter doesn't commit to another start for Ubaldo Jimenez The Sun 6/22 Orioles infielder Paul Janish will accept outright assignment to Triple-A Norfolk The Sun 6/22 Mark Trumbo's longest slump as an Oriole starts to turn with home run The Sun 6/22 Following tribute to fallen deputies, IronBirds roll over Auburn in home opener, 7-0 The Sun 6/22 Bowie a stop along the way for skippers, too The Sun 6/22 Orioles reliever Brian Duensing to have elbow surgery Friday; Ashur Tolliver recalled from Triple-A The Sun 6/22 Orioles on deck: What to watch Wednesday vs. Padres The Sun 6/22 Inbox: Will O's target starters at Deadline? MLB.com 6/23 Jimenez makes most of spot start MLB.com 6/22 Machado set to return for O's opener vs. -

BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 the Game I’Ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams As Told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer Recalls Opening Day Walk-Off Homer

CONTENTS January/February 2016 — Volume 75. No. 1 FEATURES 9 Warmup Tosses by Bob Kuenster Royals Personified Spirit of Winning in 2015 12 2015 All-Star Rookie Team by Mike Berardino MLB’s top first-year players by position 16 Jake Arrieta: Pitcher of the Year by Patrick Mooney Cubs starter raised his performance level with Cy Young season 20 Bryce Harper: Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan MVP year is only the beginning for young star 24 Kris Bryant: Rookie of the Year by Bruce Levine Cubs third baseman displayed impressive all-around talent in debut season 30 Mark Melancon: Reliever of the Year by Tom Singer Pirates closer often made it look easy finishing games 34 Prince Fielder: Comeback Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan Slugger had productive season after serious injury 38 Farewell To Yogi Berra by Marty Appel Yankee legend was more than a Hall of Fame catcher MANNY MACHADO Orioles young third 44 Strikeouts on the Rise by Thom Henninger baseman is among the game’s elite stars, page 52. Despite many changes to the game over the decades, one constant is that strikeouts continue to climb COMING IN BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 The Game I’ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams as told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer recalls Opening Day walk-off homer 52 Another Step To Stardom by Tom Worgo Manny Machado continues to excel 59 Baseball Profile by Rick Sorci Center fielder Adam Jones DEPARTMENTS 4 Baseball Stat Corner 6 The Fans Speak Out 28 Baseball Quick Quiz SportPics Cover Photo Credits by Rich Marazzi Kris Bryant and Carlos Correa 56 Baseball Rules Corner by SportPics 58 Baseball Crossword Puzzle by Larry Humber 60 7th Inning Stretch January/February 2016 3 BASEBALL STAT CORNER 2015 MLB AWARD WINNERS CARLOS CORREA SportPics (Top Five Vote-Getters) ROOKIE OF THE YEAR AWARD AMERICAN LEAGUE Player, Team Pos. -

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® 2 Jose Urquidy Houston Astros® Rookie 3 Manny Machado San Diego Padres 4

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® 2 Jose Urquidy Houston Astros® Rookie 3 Manny Machado San Diego Padres™ 4 Ketel Marte Arizona Diamondbacks® 5 Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® 6 Nico Hoerner Chicago Cubs® Rookie 7 Domingo Leyba Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 8 Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ 9 Brendan McKay Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 10 Nolan Arenado Colorado Rockies™ 11 Jack Flaherty St. Louis Cardinals® 12 Trent Grisham San Diego Padres™ Rookie 13 Luis Robert Chicago White Sox® Rookie 14 Shohei Ohtani Angels® 15 Pete Alonso New York Mets® 16 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ 17 Gary Sanchez New York Yankees® 18 Michel Baez San Diego Padres™ Rookie 19 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals® 20 Mookie Betts Los Angeles Dodgers® 21 Tommy Edman St. Louis Cardinals® 22 A.J. Puk Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 23 Xander Bogaerts Boston Red Sox® 24 Yu Chang Cleveland Indians® Rookie 25 Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ 26 Alex Bregman Houston Astros® 27 Isan Diaz Miami Marlins® Rookie 28 Nick Castellanos Cincinnati Reds® 29 Danny Mendick Chicago White Sox® Rookie 30 Aaron Judge New York Yankees® 31 Rhys Hoskins Philadelphia Phillies® 32 Gleyber Torres New York Yankees® 33 Shogo Akiyama Cincinnati Reds® 34 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 35 Javier Baez Chicago Cubs® 36 Travis Demeritte Detroit Tigers® Rookie 37 Aristides Aquino Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 38 Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® 39 Chad Wallach Miami Marlins® Rookie 40 Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® 41 Trevor Story Colorado Rockies™ 42 Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ 43 Jake Rogers Detroit Tigers® Rookie 44 Whit Merrifield Kansas City Royals® 45 Joey Gallo Texas Rangers® 46 Austin Meadows Tampa Bay Rays™ 47 Bobby Bradley Cleveland Indians® Rookie 48 Willson Contreras Chicago Cubs® 49 Marcus Semien Oakland Athletics™ 50 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. -

2013 Topps Finest Baseball HITS Grid (Does Not Include Buyback Autos Or RC Redemption Program Autos/100)

2013 Topps Finest Baseball HITS Grid (Does not include BuyBack Autos or RC Redemption Program Autos/100) TEAM RC Auto Relic Prodigies All Star Master Dual Triple Boxtopper Jered Weaver Jered Weaver Josh Hamilton Angels n/a n/a Mike Trout Mike Trout Mike Trout Josh Hamilton Josh Hamilton Mike Trout Mike Trout Astros n/a Jarred Cosart n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Athletics n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Yoenis Cespedes n/a n/a Blue Jays n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Jose Bautista n/a B.J. Upton Braves Evan Gattis Evan Gattis n/a n/a n/a n/a Jason Heyward n/a Justin Upton Brewers n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Carlos Martinez Carlos Martinez Shelby Miller Cardinals Shelby Miller n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Shelby Miller Trevor Rosenthal Trevor Rosenthal Cubs n/a Kyuji Fujikawa n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Adam Eaton Adam Eaton Alfredo Marte Adam Eaton Diamondbacks Didi Gregorius n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Didi Gregorius Didi Gregorius Tyler Skaggs Tyler Skaggs Hyun-Jin Ryu Hyun-Jin Ryu Dodgers n/a Paco Rodriguez Yasiel Puig n/a n/a n/a Hyun-Jin Ryu Yasiel Puig Yasiel Puig Buster Posey Giants n/a n/a n/a Buster Posey Buster Posey n/a Buster Posey Matt Cain Indians n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Brandon Maurer Brandon Maurer Mariners n/a Felix Hernandez n/a n/a Felix Hernandez n/a Mike Zunino Mike Zunino Christian Yelich Jose Fernandez Marlins Jose Fernandez n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Adieny Hechavarria Rob Brantly Mets Jeurys Familia Zack Wheeler n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Nationals n/a Anthony Rendon Bryce Harper Bryce Harper n/a n/a n/a n/a Dylan Bundy Adam Jones Dylan Bundy Manny Dylan Bundy Dylan Bundy Orioles L.J. -

Today's Starting Lineups

BALTIMORE ORIOLES (16-9) at BOSTON RED SOX (14-12) Game #27 ● Wednesday, May 3, 2017 ● Fenway Park, Boston, MA BALTIMORE ORIOLES AVG HR RBI PLAYER POS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AB R H RBI .182 0 0 23-Joey Rickard RF .284 4 11 10-Adam Jones CF .226 6 16 13-Manny Machado 3B .206 2 12 45-Mark Trumbo DH .221 3 6 19-Chris Davis L 1B .291 5 16 6-Jonathan Schoop 2B .222 5 13 16-Trey Mancini LF .190 1 6 2-J.J. Hardy SS .172 1 3 36-Caleb Joseph C R H E LOB PITCHERS DEC IP H R ER BB SO HR WP HB P/S GAME DATA 39-RHP Kevin Gausman (1-2, 7.50) Official Scorer: Mike Shalin 1st Pitch: Temp: Gam e Time: Attendance: 2-J.J. Hardy, INF 23-Joey Rickard, OF 39-Kevin Gausman, RHP 60-Mychal Givens, RHP BAL Bench BAL Bullpen 3-Ryan Flaherty, INF 25-Hyun Soo Kim, OF 40-Roger McDowell (Pitching) 75-Alan Mills (Bullpen) 6-Jonathan Schoop, INF 26-Buck Showalter (Manager) 45-Mark Trumbo, OF 77-John Russell (Bench) Left Left 10-Adam Jones, OF 27-Francisco Peña, C 47-Scott Coolbaugh (Hitting) 88-Howie Clark (Asst. Hitting) 3-Ryan Flaherty 48-Richard Bleier 11-Bobby Dickerson (3rd Base) 29-Welington Castillo, C* 48-Richard Bleier, LHP 12-Seth Smith 53-Zach Britton 12-Seth Smith, OF 30-Chris Tillman, RHP* 51-Alec Asher, RHP * 10-day Disabled List 25-Hyun Soo Kim 58-Donnie Hart 13-Manny Machado, INF 31-Ubaldo Jiménez, RHP 53-Zach Britton, LHP ^ 60-day Disabled List 14-Craig Gentry, OF 35-Brad Brach, RHP 54-Anthony Santander, OF* Right Right 16-Trey Mancini, OF 36-Caleb Joseph, C 55-Einar Díaz (Coach) 14-Craig Gentry 35-Brad Brach 19-Chris Davis, INF 37-Dylan Bundy, RHP -

A's NEWS LINKS, WEDNESDAY, JULY 11, 2018 BASEBALL RELATED ARTICLES ATHLETICS.COM Lowrie

A’S NEWS LINKS, WEDNESDAY, JULY 11, 2018 BASEBALL RELATED ARTICLES ATHLETICS.COM Lowrie: 1st ASG selection is 'pretty special' by Jane Lee https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/jed-lowrie-makes-first-career-all-star-team/c-285156922 A's rally to force extras but fall on bizarre play by Jane Lee https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/athletics-fall-on-bizarre-play-in-extras/c-285264940 SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE Yes, A’s Jed Lowrie is an All Star, but players’ voting needs fixing by John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/shea/article/A-s-Jed-Lowrie-named-to-All-Star-team-but- 13064184.php A’s send Frankie Montas down to get work during All-Star break by Susan Slusser https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-send-Frankie-Montas-down-to-get-work-during- 13064155.php A’s Jed Lowrie named to All-Star team as a replacement by Susan Slusser https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-Jed-Lowrie-named-to-All-Star-team-as-a- 13064104.php A’s tie Astros late, fall in 11th on strange play; Blake Treinen takes loss by Susan Slusser https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-fight-back-for-late-late-tie-but-fall-in-13065081.php THE MERCURY NEWS Frankie Montas optioned to minors after impressive outing by Martin Gallegos https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/07/10/frankie-montas-optioned-to-minors-after-impressive- outing/ Jed Lowrie’s snub is righted, named to first All-Star Game of his career by Martin Gallegos https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/07/10/jed-lowries-snub-is-righted-named-to-first-all-star-game- of-his-career/ Bizarre ending