Final Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADP Draft Resolution: We Call for an End To

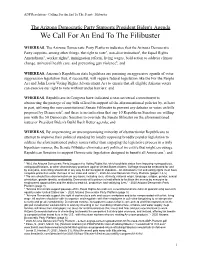

ADP Resolution - Calling For An End To The Senate Filibuster The Arizona Democratic Party Supports President Biden's Agenda We Call For An End To The Filibuster WHEREAS, The Arizona Democratic Party Platform indicates that the Arizona Democratic Party supports, among other things, the right to vote1, non-discrimination2, the Equal Rights Amendment3, worker rights4, immigration reform, living wages, bold action to address climate change, universal health care, and preventing gun violence5; and WHEREAS, Arizona’s Republican state legislators are pursuing an aggressive agenda of voter suppression legislation that, if successful, will require federal legislation like the For the People Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to ensure that all eligible Arizona voters can exercise our right to vote without undue barriers; and WHEREAS, Republicans in Congress have indicated a near-universal commitment to obstructing the passage of any bills offered in support of the aforementioned policies by, at least in part, utilizing the non-constitutional Senate Filibuster to prevent any debates or votes on bills proposed by Democrats6, and there is no indication that any 10 Republican Senators are willing join with the 50 Democratic Senators to override the Senate filibuster on the aforementioned issues or President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda; and WHEREAS, By empowering an uncompromising minority of obstructionist Republicans to attempt to improve their political standing by loudly opposing broadly popular legislation to address the aforementioned policy issues rather than engaging the legislative process in a truly bipartisan manner, the Senate filibuster eliminates any political incentive that might encourage Republican Senators to support Democratic legislation designed to benefit all Americans7; and 1 “We[, the Arizona Democratic Party,] support the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits states from imposing voting policies, voting qualifications, or other discriminatory practices against United States citizens. -

VOTER INTIMIDATION V

1 Sarah R. Gonski (# 032567) PERKINS COIE LLP 2 2901 North Central Avenue, Suite 2000 Phoenix, Arizona 85012-2788 3 Telephone: 602.351.8000 Facsimile: 602.648.7000 4 [email protected] 5 Attorney of Record for Plaintiff 6 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 8 DISTRICT OF ARIZONA 9 Arizona Democratic Party, No. __________________ 10 Plaintiffs, 11 VOTER INTIMIDATION v. COMPLAINT PURSUANT TO 12 THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF Arizona Republican Party, Donald J. Trump 1965 AND THE KU KLUX KLAN 13 for President, Inc., Roger J. Stone, Jr., and ACT OF 1871 Stop the Steal, Inc., 14 Defendants. 15 16 17 Plaintiff Arizona Democratic Party hereby alleges as follows: 18 INTRODUCTION 19 20 1. The campaign of Donald J. Trump (the “Trump Campaign”), Trump’s close 21 advisor Roger J. Stone, Jr., Stone’s organization Stop the Steal Inc., the Arizona 22 Republican Party (“ARP”), and others are conspiring to threaten, intimidate, and thereby 23 prevent minority voters in urban neighborhoods from voting in the 2016 election. The 24 presently stated goal of the Trump Campaign, as explained by an unnamed official to 25 Bloomberg News on October 27, is to depress voter turnout—in the official’s words: “We 26 have three major voter suppression operations under way” that target Latinos, African 27 Americans, and other groups of voters. While the official discussed communications 28 1 strategies designed to decrease interest in voting, it has also become clear in recent weeks 2 that Trump has sought to advance his campaign’s goal of “voter suppression” by using the 3 loudest microphone in the nation to implore his supporters to engage in unlawful 4 intimidation at Arizona polling places. -

Minutes 10 3 19

SANTA CLARA COUNTY DEMOCRATIC CENTRAL COMMITTEE 7:00 PM, South Bay Labor Council, Hall A, 2102 Almaden Rd, San Jose CA Meeting will start at 7:00 pm sharp MINUTES for Thursday, October 3, 2019 1. CALL TO ORDER 7:03 pm 2. ROLL CALL Absent: Gilbert Wong, Michael Vargas, Deepka Lalwani, Tony Alexander, Tim Orozco, Aimee Escobar, Maya Esparza, Andres Quintero, Juan Quinones, Omar Torres, Jason Baker, Rebeca Armendariz Alternates for: Ash Kalra, Evan Low, Bob Wieckowski, Jim Beall, Bill Monning, Zoe Lofgren, Anna Eshoo, Jimmy Panetta 3. IDENTIFICATION OF VISITORS Nora Campos, Candidate for State Senate SD-15 Natasha Gupta Alex Nunez Stephanie Grossman 4. ADOPTION OF AGENDA Approved 5. APPROVAL OF MINUTES (Minutes are/will be posted at sccdp.org) a. Thursday, August 1, 2019 – approved b. Thursday, September 5, 2019 – approved with correction 6. OLD BUSINESS a. Update re Director of Inclusion and Diversity; link to apply: https://tiny.cc/inclusion_director Members interested in applying please use link 7. NEW BUSINESS a. Presentation: Moms Demand Action – Teresa Fiss b. Resolution to Support the San Jose Fair Elections Initiative- Sergio Jimenez, Professor Percival, and Jeremy Barousse Vote: Approved 34 Ayes, 2 Noes, 4 Abstains. Resolution to be referred to Platform Committee c. Resolution Requesting Consistent Messaging and Training – Avalanche Democratic Club Vote: Approved Unanimously with the following text change on 4th paragraph “…to invest in data mining, technology and multi-disciplinary and other experts……” d. Report: Keith Umemoto, DNC Member & Western Region Vice Chair See Report below e. South Bay Democratic Coalition accreditation request Motion to approve unanimous 8. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

(1 of 432) Case:Case 18-15845,1:19-cv-01071-LY 01/27/2020, Document ID: 11574519, 41-1 FiledDktEntry: 01/29/20 123-1, Page Page 1 1 of of 432 239 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL No. 18-15845 COMMITTEE; DSCC, AKA Democratic Senatorial Campaign D.C. No. Committee; THE ARIZONA 2:16-cv-01065- DEMOCRATIC PARTY, DLR Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. OPINION KATIE HOBBS, in her official capacity as Secretary of State of Arizona; MARK BRNOVICH, Attorney General, in his official capacity as Arizona Attorney General, Defendants-Appellees, THE ARIZONA REPUBLICAN PARTY; BILL GATES, Councilman; SUZANNE KLAPP, Councilwoman; DEBBIE LESKO, Sen.; TONY RIVERO, Rep., Intervenor-Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Arizona Douglas L. Rayes, District Judge, Presiding (2 of 432) Case:Case 18-15845,1:19-cv-01071-LY 01/27/2020, Document ID: 11574519, 41-1 FiledDktEntry: 01/29/20 123-1, Page Page 2 2 of of 432 239 2 DNC V. HOBBS Argued and Submitted En Banc March 27, 2019 San Francisco, California Filed January 27, 2020 Before: Sidney R. Thomas, Chief Judge, and Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain, William A. Fletcher, Marsha S. Berzon*, Johnnie B. Rawlinson, Richard R. Clifton, Jay S. Bybee, Consuelo M. Callahan, Mary H. Murguia, Paul J. Watford, and John B. Owens, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge W. Fletcher; Concurrence by Judge Watford; Dissent by Judge O’Scannlain; Dissent by Judge Bybee * Judge Berzon was drawn to replace Judge Graber. Judge Berzon has read the briefs, reviewed the record, and watched the recording of oral argument held on March 27, 2019. -

League of Women Voters of Alaska Supports Ballot Measure 2'S

League of Women Voters of Alaska Supports Ballot Measure 2’s Election Reform Policies Statement from Judy Andree, President, League of Women Voters of Alaska: The League of Women Voters of Alaska supports Ballot Measure 2 and we encourage Alaskans to vote Yes on 2 this November. Election system reform in Alaska has the potential to create more authentic representation among our diverse communities and to break through the barriers holding back women, people of color, young people, and other historically marginalized groups from getting involved in politics. Our current election system limits competition, making it difficult for challengers to win. Better government and public policy depends upon elected officials who lead from values and truly understand the unique needs of the communities they represent. Ballot Measure 2 will ensure that voters are empowered with more choices on Election Day - both by creating a single unified primary ballot open to all voters, regardless of party affiliation, and by instituting ranked choice voting in general elections. In addition, eliminating “Dark Money” will improve the transparency and integrity of our electoral process once the true identity of who is backing and influencing political candidates is revealed thanks to stricter reporting requirements for large campaign contributions. Our review of these three election reforms offered by Ballot Measure 2 determined that the initiative advances the goals of the League of Women Voters and meets all eight criteria for assessing whether a proposed electoral -

2019 Sempra Energy Corporate Political Contributions Candidate

2019 Sempra Energy Corporate Political Contributions Candidate Political Party Office Sought ‐ District Name Amount Becerra, Xavier Democratic CA State Assembly$ 7,800 Aguiar‐Curry, Cecilia Democratic CA State Assembly$ 6,700 Arambula, Joaquin Democratic CA State Assembly$ 1,500 Berman, Marc Democratic CA State Assembly$ 2,000 Bigelow, Frank Republican CA State Assembly$ 4,700 Bonta, Rob Democratic CA State Assembly$ 2,000 Brough, Bill Republican CA State Assembly$ 4,700 Burke, Autumn Democratic CA State Assembly$ 6,700 Calderon, Ian Democratic CA State Assembly$ 6,200 Carrillo, Wendy Democratic CA State Assembly$ 4,700 Cervantes, Sabrina Democratic CA State Assembly$ 3,000 Chau, Ed Democratic CA State Assembly$ 1,000 Chen, Phillip Republican CA State Assembly$ 7,200 Choi, Steven Republican CA State Assembly$ 2,500 Cooper, Jim Democratic CA State Assembly$ 9,400 Cooley, Ken Democratic CA State Assembly$ 3,000 Cunningham, Jordan Republican CA State Assembly$ 9,400 Dahle, Megan Republican CA State Assembly$ 9,400 Daly, Tom Democratic CA State Assembly$ 9,400 Diep, Tyler Republican CA State Assembly$ 8,200 Eggman, Susan Democratic CA State Assembly$ 3,000 Flora, Heath Republican CA State Assembly$ 9,400 Fong, Vince Republican CA State Assembly$ 3,000 Frazier, Jim Democratic CA State Assembly$ 4,700 Friedman, Laura Democratic CA State Assembly$ 3,500 Gallagher, James Republican CA State Assembly$ 4,000 Garcia, Cristina Democratic CA State Assembly$ 4,700 Garcia, Eduardo Democratic CA State Assembly$ 4,000 Gipson, Mike Democratic CA State -

Arizona Democratic Party Regular Meeting of the ADP State Committee Saturday, May 30, 2020 Virtual Meeting, Phoenix, Arizona

DRAFT Arizona Democratic Party Regular Meeting of the ADP State Committee Saturday, May 30, 2020 Virtual Meeting, Phoenix, Arizona Chair Felecia Rotellini called the meeting of the ADP State Committee to order at 10:00 am. Parliamentarian Jeanne Lunn provided an overview as to how to use the GoTo Webinar platform. The video “Why I am a Democrat” was shown; Rotellini then led the Pledge of Allegiance and introduced several guest speakers. Muthoni Wambu Kraal, DNC Political Director, talked about how the party is working together to elect strong leaders and is building one of our strongest inter-generational benches. She said that Arizona is a true battleground state and will be carrying much for the country. Currently the DNC has invested around $1 million in Arizona through various programs for this election and is particularly focused on outreach and organizing. New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham said that while all elections important, this one can help us change all the policies that are preventing us from supporting our families and communities, both in Arizona and across the country. She discussed the transformation that Democrats have made in New Mexico over the past decade or so – following the 2018 election, the entire Congressional delegation and every statewide office was won by a Democrat and more women were elected to statewide office and appellate courts. In one year, new policies regarding the environment, voting, the minimum wage, funding for education, and more have been put in place. Additionally, New Mexico has been a leader in terms of response to the pandemic. -

Barry Goldwater a Team of Amateurs and the Rise of Conservatism Nicholas D'angelo Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2014 In Reckless Pursuit: Barry Goldwater A Team of Amateurs and the Rise of Conservatism Nicholas D'Angelo Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation D'Angelo, Nicholas, "In Reckless Pursuit: Barry Goldwater A Team of Amateurs and the Rise of Conservatism" (2014). Honors Theses. 508. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/508 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Reckless Pursuit: Barry Goldwater, A Team of Amateurs and the Rise of Conservatism By Nicholas J. D’Angelo ***** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June 2014 In Reckless Pursuit | i ABSTRACT D’ANGELO, NICHOLAS J. In Reckless Pursuit: Barry Goldwater, A Team of Amateurs and the Rise of Conservatism Department of History, Union College, June 2014 ADVISOR: Andrew J. Morris, Ph.D. Before 1964, Barry Goldwater had never lost an election. In fact, despite being the underdog in both of his U.S. Senate elections in Arizona, in 1952 and 1958, he defied the odds and won. His keen ability for organization, fundraising and strategy was so widely respected that his Republican colleagues appointed the freshman senator to chair their campaign committee in 1955, with conservatives and liberals alike requesting his aid during contentious elections. -

114Th Congress 13

ARIZONA 114th Congress 13 Office Listings—Continued Chief of Staff.—Oliver Schwab. FAX: 225–0096 Scheduler.—Kyle Souza. Legislative Director / Deputy Chief of Staff.—Beau Brunson. Communications Director.—Kyle Souza. 10603 North Hayden Road, Suite 108, Scottsdale, AZ 85260 ................................................. (480) 946–2411 FAX: 946–2446 Counties: MARICOPA (part). CITIES AND TOWNSHIPS: Fountain Hills, Paradise Valley, Cave Creek, Carefree, Rio Verde, Scottsdale, Phoenix (part), Yavapai Nation, and Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Community. Population (2010), 754,482. ZIP Codes: 85020, 85022–24, 85027–29, 85032, 85050, 85054, 85201, 85250–51, 85253–56, 85258–60, 85264, 85268 *** SEVENTH DISTRICT RUBEN GALLEGO, Democrat, of Phoenix, AZ; born in Chicago, IL, November 20 1979; education: A.B., Harvard, Cambridge MA, 2004; professional: Delegate, Democratic National Convention 2008; Chief of Staff to Phoenix Councilman Michael Nowakowski 2008–10; vice- chair, Arizona Democratic Party 2009; Member of the Arizona House of Representatives, 2011– 14; Assistant Democratic Leader for the Arizona House of Representatives, 2013–2014; mili- tary: United States Marine Corps, 2000–06; awards: Combat Action Ribbon; religion: Catholic; married: Phoenix Councilwoman Kate Gallego; caucuses: Congressional Hispanic Caucus; Con- gressional Progressive Caucus; Congressional LGBT Equality Caucus; Post 9/11 Veterans Cau- cus; Quiet Skies Caucus; Medicaid Expansion Caucus; committees: Armed Services; Natural Resources; elected to the 114th Congress on November 4, 2014. Office Listings https://rubengallego.house.gov twitter @reprubengallego www.facebook.com/reprubengallego 1218 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–4065 Scheduler.—Rome Hall. 411 North Central Avenue, Suite 150, Phoenix, AZ 85004 ..................................................... (602) 256–0551 District Director.—Luis Heredia. Counties: MARICOPA (part). -

Roots in History, Vision for the Future 2020 Arizona Democratic Party

2020 Arizona Democratic Party Platform Roots in History, Vision for the Future Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 “We the people of the United States...”................................................................................3 “...to form a more perfect union...” ........................................................................................4 “...establish justice...” ...................................................................................................................5 “...insure domestic tranquility...”.............................................................................................6 “...provide for the common defense...” .................................................................................7 “...promote the general welfare...” .........................................................................................8 “...secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity...” .......................9 2020 ADP Platform 1.25.2020 1 2020 Arizona Democratic Party Platform Roots in History, Vision for the Future We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. The United States -

Haldane Board Names New Superintendent Candidates Go

Beacon Second Saturday events — see Calendar | Daylight Saving Time begins Sunday at 2 a.m. Set clocks forward one hour FRIDAY, MARCH 7, 2014 69 MAIN ST., COLD SPRING, N.Y. | www.philipstown.info Candidates Go Head-to-Head in Election Forum Fundamental differences on village issues By Michael Turton he four candidates vying for two seats on the Cold Spring Village TBoard in the upcoming election met in a freewheeling forum Monday (March 3), hosted by The Paper/Philip- stown.info. A full house at Haldane’s mu- sic room watched as incumbent Trustee Matt Francisco and running mate Don- ald MacDonald faced off with Cathryn Fadde and Michael Bowman. Moderator Gordon Stewart, The Paper’s publisher, gave the candidates free rein, produc- ing a four-way conversation that was reserved early on but later turned testy. The complete forum can be viewed on Leandra Rice jumps for joy at a recent Anything Goes rehearsal, as sailors and chorus girls look on. See story on page 7. Philipstown.info. Photo by Jim Mechalakos Introducing the candidates The candidates’ opening statements set the tone. Fadde and Bowman empha- Haldane Board Names New Superintendent sized the need to improve village gov- Administrator assumes the site visit, praised Bowers. Horn said: ernment processes in order to complete “You really get a chance to meet that per- outstanding projects while Francisco responsibilities July 1 son, seeing them in their home district. and MacDonald stressed that their cre- It was awesome and we have a lot to look dentials will help get projects done while By Pamela Doan forward to. -

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Enacting the California State Budget for 2015-2016: The Governor Asks the Stockdale Question Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0283s54r Author Mitchell, DJ Publication Date 2021-06-28 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CHI\PTER 6i Enacting the California State Budget for 2015-2016: Ttre Governor Asks the Stockda le Question / \ ntb L\ t/ \' 0\ n U Danriel J.B. Mitchell Professor-Emeritus, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs ano UCLA Anderson School of Management, daniel,i.b,rnitchell@anderson,ucla,edu This article is based on information onlv l.hrough mid-August and does not reflect subsequent developments Who am l? Whv om I here? Admiral James Stockdale Ross Perot's Third Partv Vice Presidential Candidate at a 1-992 television debater Jerry Brown is the only governor to be elected to frour terms, albeit in two iterations.' Unless term limits are Iifted, no subsequent governor will match his record, But even il he had a ntore conventional gubernatorial history, i.e., if he hadn't been governor in the mid-to-late l-970s and early 1-980s, Lry 2015, he would have "owned" the condition of the state budget. After all, his second iteration began with his (rer)election as governor in 201-0. When he took off ice in January 2011-, and for six months into that terrn, he was under the budget of his predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, But by the time the 201-5-16 state: budget was being proposed and enacted, there had already been three purely Brown state budgets during his second iteration, The budget of 2O1,5-L6, whose enactment we review below, was Brown's fourth.