Case Study of Kasi Chetty Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claim by Financial Creditors

List of Creditors List of claims received & admitted up to 14 September 2018 from Financial Creditors Sr Amount of Claim Admitted Amount Name No (INR Crs.) (INR Crs.) 1 Union Bank of India 710.03 710.03 2 L&T Infra Finance Company Ltd 656.27 656.27 3 Asset Reconstruction Company of India Ltd 606.95 606.95 4 Bank Of India 614.14 567.14 5 Central Bank Of India 486.53 486.53 6 Punjab National Bank 475.37 475.37 7 Axis Bank Ltd 1,264.58 470.30 8 Allahabad Bank 315.30 315.30 9 Asset Care & Reconstruction Enterprise Ltd 207.80 207.80 10 State Bank of India 195.21 195.21 11 SSG Investment Holding India Ltd 192.29 192.29 12 Jammu & Kashmir Bank Ltd 188.52 150.19 13 Bank Of Baroda 104.82 104.74 14 Edelweiss Asset Reconstruction Company Ltd. 92.79 92.79 15 India Opportunities II Pte Ltd 68.89 68.89 16 Karnataka Bank Ltd 24.79 24.77 17 Corporation Bank 20.80 20.80 Total 6,225.08 5345.37 Note: The aforesaid is subject to further in depth verification and therefore may undergo change SECURITY INTEREST OF FINANCIAL CREDITORS IN LAVASA CORPORATION LIMITED Sr. Particulars of the Facility Brief Details of the Documents No. Financial Creditor Security Interest (as per Form C) 1. Union Bank of India For Term Loan- Prime Security I of Rs.102 (Immovable Assets): crores; Term Loan-IIA of (i) First Pari Passu Indenture of Rs.200 crores, Charge on all the Mortgage dated Term Loan 1_B present and future 21-10-2014 of Rs. -

Project Name: M/S

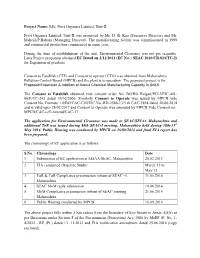

Project Name: M/s. Privi Organics Limited, Unit-II Privi Organics Limited, Unit-II was promoted by Mr. D. B. Rao (Executive Director) and Mr. Mahesh.P.Babani (Managing Director). The manufacturing facility was commissioned in 1999 and commercial production commenced in same year. During the time of establishment of the unit, Environmental Clearance was not pre requisite. Later Project proponent obtained EC Dated on 2/11/2011 (EC No. : SEAC 2010/CR.824/TC-2) for Expansion of products. Consent to Establish (CTE) and Consent to operate (CTO) was obtained from Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) and the plant is in operation. The proposed project is for Proposed Expansion & Addition of Aroma Chemical Manufacturing Capacity in Unit-II. The Consent to Establish obtained vide consent order No. BO/RO Raigad/PCI-I/EIC-421- 06/E/CC-243 dated 19/10/2006. Similarly Consent to Operate was issued by MPCB vide Consent No. Formate 1.0/BO/CAC-Cell/EIC.No.-RD-2586-13/5 th CAC-5854 dated 20/06/2014 and is valid upto 28/02/2017 and Consent to Operate was amended by MPCB Vide Consent no.: MPCB/CAC-cell/Amend/CAC-17. The application for Environmental Clearance was made to SEAC/SEIAA Maharashtra and additional ToR was issued during 80th SEAC-I meeting, Maharashtra held during 30th-31st May 2014. Public Hearing was conducted by MPCB on 16/09/2014 and final EIA report has been prepared. The chronology of EC application is as follows: S.No. Chronology Date 1 Submission of EC application at SEIAA/SEAC, Maharashtra 28.02.2013 2 EIA conducted (Baseline Study) March’13 to May’13 3 ToR & ToR Compliance presentation infront of SEAC –I, 31.05.2014 Maharashtra 4 SEAC MoM reply submission 19.06.2014 5 MoM Compliance presentation infront of SEAC meeting 21.06.2014 Maharashtra 6 Public Hearing conducted by MPCB 16.09.2014 The above project falls within 5 Km radius from the boundary of Eco-Sensitive Areas (ESA) as per Directions under Section 5 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 by MoEF (F. -

0 0 23 Feb 2021 152000417

Annexure I Annexure II ' .!'r ' .tu." "ffi* Government of Maharashtra, Directorate of Geology and Mining, "Khanij Bhavan",27, Shivaji Nagar, Cement Road, Nagpur-,1.10010 CERTIFICATE This is hereby certified that the mining lease granted to ]Ws Minerals & Metals over an area 27.45.20 Hec. situated in village Redi, Taluka Vengurla, District- Sindhudurg has no production of mineral since its originally lease deed execution. This certificate is issued on the basis of data provided by the District Collectorate, Sindhudurg. Mr*t, Place - Nagpur Director, Date - l1109/2020 Directorate of Geology and Mining, Government of Maharashtra, Nagpur 'ffi & r6nrr arn;r \k{rc sTrnrr qfrT6{ rtqailEc, ttufrg Qs, rr+at', fula rl-c, ffi qm, - YXo oqo ({lrr{ fF. osRe-?eao\e\\ t-m f. oeit-tlqqeqr f-+d , [email protected], [email protected]!.in *-.(rffi rw+m-12,S-s{r.r- x/?ol./ 26 5 5 flfii6- tocteo?o yfr, ll lsepzolo ifuflRirrs+ew, I J 1r.3TrvfdNfu{-{r rrs. \ffi-xooolq fus-q ti.H m.ffi, tu.frgq,l ffi ql* 1s.yr t ffiTq sF<-qrartq-qrsrufl -srd-d.. vs1{ cl fu€I EFro.{ srfffi, feqi,t fi q* fr.qo7o1,7qoqo. rl enqd qx fl<ato lq/os/?o?o Bq-tn Bqqri' gr{d,rr+ f frflw oTu-s +.€, r}.t* ar.ffi, fii.fufli ++d sll tir.xq t E'fr-qrqr T6 c$ Efurqgr tTer<ir+ RctsTcr{r :-err+ grd ;RrerrqTEkT squrq-d qT€t{d df,r{ +'t"qra *a eG. Tr6qrl :- irftf,fclo} In@r- t qr.{qrroi* qrqi;dqrf,q I fc.vfi.firqr|. -

Moi Sept Final

1 Editorial? The subsequent decades after independence have seen a process of institutionalisation of a democratic A fter India got independence in 1947, there were political society, but the class character of the state various pronouncements about the likelihood of it has remained feudal and hierarchical, with a clear collapsing, becoming a failed state, and breaking up continuation moreover, of colonial structures and again, on account of the weight of its own internal cultures of governance. Simultaneously however, those contradictions. The scale of the attempt to establish, who have historically been at the margins of social, in such a huge, diverse, and deeply segmented society, political, and economic power - Dalits, landless formal democracy with all its paraphernalia of a farmers, the marginal peasantry, Adivasis, and workers, parliament, universal franchise, an independent and women - have, all over the country, and through judiciary, was something that had never been tried myriad actions, constantly challenged the power and before. Sixty-two years on, India survives as a legitimacy of this feudal, hierarchical, and colonial state democracy (some say ‘thriving’, others are more and underlined its constitutional responsibilities. restrained), and is now even touted widely as an These struggles have been expressions of the needs emerging super power on the world stage. The of the time and of interest groups and developments reasons for this happening are many, but one of the at the local, regional, national, and global levels. And important – little recognised but crucial – has been the they have on several occasions and in several contexts contributions that numerous people’s movements expanded upon and given new meaning to rights, have made over the decades to the democratisation of justice, freedoms, and development. -

How Government Agencies Fast-Tracked Lavasa

How government agencies fast-tracked Lavasa By Rifat Mumtaz Lavasa, the picturesque planned hill station being developed by Hindustan Construction Company (HCC) near Pune, is facing charges of illegal land acquisition and environmental violations and construction has been stayed pending an inquiry. This article says that the focus should be not on the misdemeanours of the corporation but on the collusions and oversights of government The bureaucracy moves at snail's pace in India. But look at the speed with which the Lavasa project, currently under scrutiny from the Environment Ministry and construction stayed pending scrutiny of irregularities in sanctions granted to the project, was sanctioned. Clearance was granted within months of its application of purpose, indeed even before the application was submitted to the concerned departments and ministries! Thousands of scheduled caste and scheduled tribe families in this Mulshi-Maval region have languished for decades without caste certificates to support their legal entitlements to the land, or access to basic services. The ignorance of these poor families -- nomadic tribes (Dhangar) and tribal communities (Koli, Katkar, Thakar and Marathas) residing in small community hamlets -- worked in favour of Hindustan Construction Company (HCC) and the state of Maharashtra. Had it not been for the voices of a few concerned citizens of Pune city, who recognised the long-term implications of such a massive infrastructure project, the socio- environmental consequences of the project would never have come to light. Brand 'Lavasa' Lavasa Corporation was originally registered as Pearly Blue Lake Resort Private Limited Company, in 2000. The project was a business hotel to be developed on the banks of Warasgaon lake in Mose valley, Mulshi block, Pune district. -

GIS Steering Smart Future for Smart Indian Cities

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 4, Issue 8, August 2014 1 ISSN 2250-3153 GIS Steering Smart Future for Smart Indian Cities Anuj Tiwari, Dr. Kamal Jain Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, India. Abstract- A Smart City is the integration of technology into a dimensions to urbanization which require a quick need to strategic approach to sustainability. 21st Century has brought upgrade existing cities. The concept of a smart city is a relatively with it a new global trend of “sustainable urban development” new one. A Smart City is the integration of technology into a and this concept adds new dimensions to urbanization which strategic approach to sustainability. Although there is no clear require a quick need to upgrade existing cities. The concept of a definition to define Smart City but broadly “a city that monitors smart city is a relatively new one. Throughout the years, with and integrates conditions of all of its critical infrastructures, the significant contribution from various technologies like including roads, bridges, tunnels, rails, subways, airports, computer science, information technology, remote sensing, seaports, communications, water, power, even major buildings, advance multimedia world etc, GIS evolved from traditional can better optimize its resources, plan its preventive maintenance geographer’s or cartographer’s tool for surveying and activities, and monitor security aspects while maximizing planning to a rapidly expanding primary technology for services to its citizens is known as Smart City” [3]. Cities are understanding our planet and related geospatial opportunities to our fundamental building blocks. Throughout the history, they foster a sustainable world. -

Sanjay Balkrishna Saoji

प्रादेशिक योजना- पुणे पुणे महानगर प्रदेि क्षेत्र शिकास प्राशधकरणाची हद्दिाढ मंजूरीबाबत. महाराष्ट्र िासन नगर शिकास शिभाग, मंत्रालय, मुंबई-400 032. शनणणय क्रमांक : टीपीएस-1815/613/प्र.क्र.309/15/नशि-13, शदनांक : 04/12/2015 शनणणय : सोबतची िासशकय अशधसूचना महाराष्ट्र शासन असाधारण राजपत्रामध्ये मध्ये प्रससध्द करावी. महाराष्ट्राचे रा煍यपाल यांचे आदेिानुसार ि नांिाने, (संजय सािजी) अिर सशचि, महाराष्ट्र िासन प्रत माशहतीकशरता सादर:- 1) मा.पालक मंत्री,पुणे सजल्हा. 2) मा.मुख्यमंत्रीमहोदयांचे ससचव, मंत्रालय,मुंबई. 3) मा.रा煍यमंत्री (नसव) महोदयांचे खाजगी ससचव, मंत्रालय,मुंबई. 4) प्रधान ससचव (नसव-1) नगर सवकास सवभाग, मंत्रालय, मुंबई. प्रत माशहतीकशरता ि कायणिाहीकशरता:- 1) अध्यक्ष, पुणे सजल्हापसरषद, पुणे 2) महापौर, पुणे महानगरपासलका, पुणे. 3) महापौर, पपपरी-पचचवड महानगरपासलका, पपपरी. 4) सभापती, मावळ तालकु ा पंचायत ससमती, वडगाव, सज.पुणे. 5) सभापती, हवेली तालकु ा पंचायत ससमती, हवेली, सज.पुणे. 6) सभापती, भोर तालकु ा पंचायत ससमती, भोर, सज.पुणे. 7) सभापती, दड तालकु ा पंचायत ससमती, दड, सज.पुणे. 8) सभापती, सश셁र तालकु ा पंचायत ससमती, सश셁र, सज.पुणे. 9) सभापती, मुळशी तालकु ा पंचायत ससमती, पौड, सज.पुणे. -

District Census Handbook, Poona, Part

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK POONA Part A-Town & Village Directory Part B-Primary Census Abstract Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS OFFICE BOMBAY . PRINTED IN INOlA BY nm MANAGER. GOVERNMEN"r CENTRAL PRESS. BOMBAY. AND PUBLISHED BY "IHE DIRECTOR. GOVERNMENT PRINTING AND STATIONERY. MAHAllASHTRA STATE. BOMBAy-400 004 1974 o . .. < .. I \ i) . .\.:"._,. .•. \ ,. ~ " .,i ~ '" ~ ~ ~ , . ;,. '1- :\/ ... '\ , ,<J I ) ; I> . .... ,Ji- . .r ........ ..r..__...... :It ~ .. ~ " ,~ Q. ~ ~\........ ;;J ?i: ,.. .s: t. :;! ~ If • ..., • l- -....cc::: '" ~ -C !! CC .:z !t 0 0 A- r- I ~ ~ j CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 Central GOl'ernment Publications Census Report, Series 11-Maharashtra, is published m the following Parts- I-A and B General Report I-C Subsidiary Tables' II-A General Population Tables II-B General Economic Tables II-C Social and Cultural Tables III Establishments-Report and Tables IV Housing-Report and Tables VI-A Town Directory VI-B Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns VI-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages VII Report on Graduates and Technical Personnel VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration (For official use only) VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation (For official use only) IX Census Atlas of Maharashtra State Government Publications 26 Volumes of District Census Handbooks in English 26 Volumes of District Census Handbooks in Marathi INTRODUCTION This is the third edition of district census haildbooks brought out largely on the basis of the material collected during each decennial census of our population. Earlier editions had appeared after the 1951 and the 1961 censuses. The pr~sent volume generally follows the pattern of its predecessors in presenting the 1971 census tahles for thc district and basic, demographic, economic and general information for each village therein. -

List of Financial Creditors of Lavasa Corporation Limited

LIST OF FINANCIAL CREDITORS OF LAVASA CORPORATION LIMITED As on December 31, 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE 1. The list of creditors presented in the following pages is as of claims received till December 31, 2018 2. The list of creditors is not the final list, as the verification / reconciliation of claims is still under process and the list of creditors shall be updated as and when more claims are received and verified The aforesaid data is subject to further verification and therefore may undergo change LIST OF CLAIMS BY FINANCIAL CREDITORS OF LAVASA CORPORATION LIMITED Amount in INR crores Sr. Amount Amount Particulars of Claimant No. Claimed Verified Remarks Verified amount includes Corporate Guarantee towards 1 Union Bank of India 701.71 701.29 WAML 2 of INR 409.59 Verified amount include s Corporate Guarantee towards WPSL 2 of INR 304.28 & WAML of 2 L&T Infra Finance Company Ltd. 656.27 656.27 INR 262.60 Asset Reconstruction Company 3 of India Ltd. (ARCIL) 606.95 606.95 4 Bank of India 634.10 567.14 Verified amount includes Corporate Guarantee towards WAML of INR 152.25. Verified amount includes 3 INR 39.13 Crores pertaining to Land Parcel mortgage by LCL towards (i) Term Loan facility availed by Lavasa Hotels (INR 2.52 crores), (ii) NCD availed by HCCL (INR 5 Axis Bank Ltd. 1264.58 509.43 36.60 crores). Verified amount includes Corporate Guarantee towards 6 Central Bank of India 507.38 507.38 WAML of INR 214.52 7 Punjab National Bank 475.37 475.37 Verified amount includes 3 INR 18.02 Crores pertaining to Land parcels mortgaged by LCL for Asset Care & Reconstruction Term Loan facility availed by 8 Enterprise Ltd.