Walk Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulars Features

Number 601 February 2014 Saw-whet owl photographed at Ashbridges Bay by Lynn Pady FEATURES REGULARS 9 Coming Events 19 Snake Habitat Creation Extracts from Outings Reports 8 Walking in Nature 10 Monthly Meetings Notice 3 Toronto’s Saxifrage Family 12 Monthly Meeting Report 7 TFN Slide Collection: Update 14 President’s Report 6 Owls in Toronto 15 TFN Outings 4 Message from Environmental 16 19 Weather – This Time Last Year Commissioner of Ontario Take Action to Conserve Nature 17 Grant Report from High Park Nature Centre 18 TFN 601-2 Toronto Field Naturalist February 2014 Toronto Field Naturalist is published by the Toronto Field BOARD OF DIRECTORS Naturalists, a charitable, non-profit organization, the aims of President & Outings Margaret McRae which are to stimulate public interest in natural history and Past President Bob Kortright to encourage the preservation of our natural heritage. Issued Vice President & monthly September to December and February to May. Monthly Lectures Nancy Dengler Views expressed in the Newsletter are not necessarily those Secretary-Treasurer Charles Crawford of the editor or Toronto Field Naturalists. The Newsletter is printed on 100% recycled paper. Communications Alexander Cappell Membership & Newsletter Judy Marshall ISSN 0820-636X Newsletter Vivienne Denton Monthly Lectures Lavinia Mohr IT’S YOUR NEWSLETTER! Nature Reserves & Outings Charles Bruce- We welcome contributions of original writing of observa- Thompson tions on nature in and around Toronto (up to 500 words). Outreach Stephen Kamnitzer We also welcome reports, reviews, poems, sketches, paint- Webmaster Lynn Miller ings and digital photographs. Please include “Newsletter” Anne Powell in the subject line when sending by email, or on the enve- lope if sent by mail. -

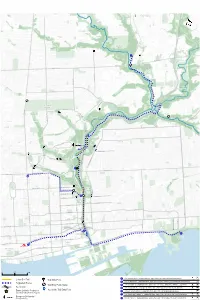

Sec 2-Core Circle

TRANSFORMATIVE IDEA 1. THE CORE CIRCLE Re-imagine the valleys, bluffs and islands encircling the Downtown as a fully interconnected 900-hectare immersive landscape system THE CORE CIRLE 30 THE CORE CIRLE PUBLIC WORK 31 TRANSFORMATIVE IDEA 1. THE CORE CIRCLE N The Core Circle re-imagines the valleys, bluffs and islands E encircling the Downtown as a fully connected 900-hectare immersive landscape system W S The Core Circle seeks to improve and offer opportunities to reconnect the urban fabric of the Downtown to its surrounding natural features using the streets, parks and open spaces found around the natural setting of Downtown Toronto including the Don River Valley and ravines, Lake Ontario, the Toronto Islands, Garrison Creek and the Lake Iroquois shoreline. Connecting these large landscape features North: Davenport Road Bluff, Toronto, Canada will create a continuous circular network of open spaces surrounding the Downtown, accessible from both the core and the broader city. The Core Circle re- imagines the Downtown’s framework of valleys, bluffs and islands as a connected 900-hectare landscape system and immersive experience, building on Toronto’s strong identity as a ‘city within a park’ and providing opportunities to acknowledge our natural setting and connect to the history of our natural landscapes. East: Don River Valley Ravine and Rosedale Valley Ravine, Toronto, Canada Historically, the natural landscape features that form the Core Circle were used by Indigenous peoples as village sites, travelling routes and hunting and gathering lands. They are regarded as sacred landscapes and places for spiritual renewal. The Core Circle seeks to re-establish our connection to these landscapes. -

Enbridge Gas Inc. Advisor, Regulatory Applications [email protected] 500 Consumers Road Regulatory Affairs North York, Ontario M2J 1P8 Canada

Alison Evans tel 416 495 5499 Enbridge Gas Inc. Advisor, Regulatory Applications [email protected] 500 Consumers Road Regulatory Affairs North York, Ontario M2J 1P8 Canada VIA Email and RESS August 4, 2020 Ms. Christine Long Board Secretary Ontario Energy Board 2300 Yonge Street, Suite 2700 Toronto, Ontario, M4P 1E4 Dear Ms. Long: Re: Enbridge Gas Inc. (“Enbridge Gas”) Ontario Energy Board (“Board”) File No.: EB-2018-0108 NPS 30 Don River Replacement Project (“Project”) On November 29, 2018 the Board issued its Decision and Order for the above noted proceeding which included, as Schedule B, several Conditions of Approval. Per section 6. (a) in the aforementioned Decision and Order, Enbridge Gas is to provide the Board with a post construction report no later than three months after the in-service date. Please find enclosed a copy of the Post Construction report for the NPS 30 Don River Replacement project. Please contact me if you have any questions. Yours truly, (Original Digitally Signed) Alison Evans Advisor Rates Regulatory Application NPS 30 Don River Replacement: Post-Construction Interim Monitoring Report EB-2018-0108 Company: Enbridge Gas Inc. Enbridge Gas Inc. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Description .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Waterfront Toronto Annual Report

June 28, 2018 Annual Report 2017/2018 2017/18 Annual Report / Contents Surveying by the Keating Channel. This work is related to the Cherry Street lakefilling project, part of the $1.25-billion Port Lands flood protection initiative, which began in December 2017. See pages 26-31 for more on this transformative project. 11 Vision 13 Message from the Chair 15 Message from the CEO 16 Who we are 17 Areas of focus 18 Our board 19 Committees and panels 21 Projects 24 What we achieved in 2017/18 26 The Port Lands 32 Complete Communities 36 Quayside 40 Public Places 44 Eastern Waterfront Transit 48 Financials 52 Capital investment 53 Capital funding 54 Corporate operating costs 55 Corporate capital costs 56 Resilience and risk management 59 Appendix I 63 Appendix 2 64 Executive team 2 3 Waterfront Toronto came together in 2001 to tackle big issues along the waterfront that only powerful collaboration across all three orders of government could solve. So far we’ve transformed over 690,000 square metres of land into active and welcoming public spaces that matter to Torontonians. A midsummer edition of Movies on the Common, a free public screening series at Corktown Common. The centrepiece of the emerging West Don Lands neighbourhood, Corktown Common is a 7.3-hectare Waterfront Toronto park that quickly became a beloved local gathering place after it opened in 2014. 4 5 Today, we’re creating a vibrant and connected waterfront that belongs to everyone. And we face one of the most exciting city- building opportunities on earth. -

Planning Parks and Open Space Networks in Urban Neighbourhoods

Planning parks and open space networks in MAKING urban neighbourhoods CONNECTIONS– 1 – What we’re all about: Toronto Park People is an independent charity that brings people and funding together to transform communities through better parks by: CONNECTING a network of over RESEARCHING challenges and 100 park friends groups opportunities in our parks WORKING with funders to support HIGHLIGHTING the importance innovative park projects of great city parks for strong neighbourhoods ORGANIZING activities that bring people together in parks BUILDING partnerships between communities and the City to improve parks Thank you to our funders for making this report possible: The Joan and Clifford The McLean Foundation Hatch Foundation Cover Photo: West Toronto Railpath. Photographed by Mario Giambattista. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................4 Introduction ....................................................................7 Planning for a network of parks and open spaces ......9 What are we doing in Toronto? ................................... 12 The downtown challenge ....................................... 15 The current park system downtown ...................... 17 8 Guiding Principles Opportunities in Downtown Toronto .....................40 For Creating a Connected Parks and Open Space Garrison Creek Greenway ........................................... 41 System in Urban Neighbourhoods..........................20 The Green Line .............................................................42 -

Regulars Features

Number 605 September 2014 Orange sulphur butterfly on grass-leaved goldenrod at Leslie Street Spit. Photo: Augusta Takeda. See note on page 6. REGULARS 19 FEATURES Coming Events Extracts from Outings Reports 8 Common Tern Raft Retrofit 9 12 For Reading Ground Cherries 13 From the Archives 16 Bird’s Nest Fungus 15 In the News 18 15 Keeping in Touch 14 Corktown Common: a new park for Toronto Monthly Meetings Notice 3 Toronto Wildlife Centre Open House 17 7 Monthly Meeting Report TFN Grants Awarded 2014-2015 17 President’s Report 6 TFN Outings 4 Weather – This Time Last Year 16 TFN 605-2 Toronto Field Naturalist September 2014 Toronto Field Naturalist is published by the Toronto Field BOARD OF DIRECTORS Naturalists, a charitable, non-profit organization, the aims of President & Outings Margaret McRae which are to stimulate public interest in natural history and Past President Bob Kortright to encourage the preservation of our natural heritage. Issued Vice President & monthly September to December and February to May. Monthly Lectures Nancy Dengler Views expressed in the Newsletter are not necessarily those Secretary-Treasurer Charles Crawford of the editor or Toronto Field Naturalists. The Newsletter is printed on 100% recycled paper. Communications Alexander Cappell Membership & Newsletter Judy Marshall ISSN 0820-636X Newsletter Vivienne Denton Monthly Lectures Lavinia Mohr IT’S YOUR NEWSLETTER! Nature Reserves & Outings Charles Bruce- We welcome contributions of original writing of Thompson observations on nature in and around Toronto (up to 500 Outreach Stephen Kamnitzer words). We also welcome reports, reviews, poems, Webmaster Lynn Miller sketches, paintings and digital photographs. -

Waterfront Toronto Rolling Five-Year Strategic Plan

December 6, 2018 2019/20–2023/24 Waterfront Toronto / Rolling Five-Year Strategic Plan / Past · Present · Future Toronto is at a critical juncture. It has a strong and diversified economy, The Opportunity a thriving cultural life, and has earned a growing international reputation for Toronto, as a welcoming destination for visitors and new immigrants. At the same time, like other cities around the world Toronto is working to address an Ontario, array of challenges associated with economic inequality, affordability, and Canada mobility and environmental sustainability. The challenges many cities face today are products of their growth and success. Urbanization is a major global trend: 55% of humanity already lives in cities, and the UN projects that this figure will reach 68% by 2050. The Greater Toronto Area is home to nearly half of Ontarians (48.3%), a share that’s expected to keep growing. Toronto’s assets and systems —from housing to roads to transit—are strained precisely because so many people want to live and work here. In addition to facing challenges associated with its growth, Toronto is navigating trends that are shaping life across many jurisdictions. Toronto’s neighbourhoods have become more fractured along lines of income and identity. Opportunities related to technological and economic change have been unevenly distributed. Variations in social capital and trust leave some residents at increased risk of isolation. And extreme weather is becoming more frequent, raising concerns about the resilience of our built environment. Over the next five years, Toronto—and by extension Ontario and Canada, whose economies and reputations are tied to their largest city—has an opportunity to address some of the pressing urban problems of our time, growing economically while thriving socially and culturally. -

3. Living City Report Card 2016

24 The Living City® Report Card 2016 WATER The Living City® Report Card 2016 25 WHY DOES WATER MATTER? Water is one of the most important substances on earth. Directly or indirectly, water affects all facets of life. Clean water is necessary for commercial activities such as agriculture, fishing, and manufacturing. It is important for recreational activities such as swimming and boating. The biodiversity of our streams and lakes depends on clean water and so does our own health and well-being. Clean water is a precious and limited resource that should be valued and protected. 26 The Living City Report Card 2011 The Living City® Report Card 2016 27 2016 Water Quality (TRCA) PROGRESS TARGET MET almost Although conditions are similar to those reported in 2011, stream water quality remains a concern in the Toronto region. In recent years, there were fewer exceedances of water quality objectives but when the objectives were exceeded, concentrations were higher than they have been in the past. Concerns include nutrients that contribute to growth of algae, chloride (mostly from road salt) because of its negative impact on aquatic organisms, and Escherichia coli (E. coli) which is a potentially unhealthy bacteria. Stream water quality reflects the input of pollutants from surrounding land uses and can directly influence aquatic habitat and communities. Improved stormwater management in both rural and urban areas, as well as continued efforts by municipalities and individual homeowners to reduce the use of fertilizer and road salt is needed to help improve the quality of water in the Toronto region. THE CURRENT SITUATION There have also been some changes we did not want to see. -

Downtown PPR Plan

Down- town Parks and Public Realm Plan Downtown Parks and Public Realm Plan Acknowledgements We acknowledge that the City of Toronto is located on the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat Confederacy, the Haudenasaunee Confederacy, the Mississaugas of New Credit First Nation, and the Métis people, and is home to many diverse Indigenous peoples. We acknowledge them and others who care for the land as its past, present and future stewards. Prepared for the City of Toronto 2018 City of Toronto team: City Planning Parks, Forestry and Recreation Transportation Services Prepared by: PUBLIC WORK In collaboration with: GEHL STUDIO / NEW YORK SWERHUN ASSOCIATES SAM SCHWARTZ CONSULTING LLC II PUBLIC WORK III What Kind of City Were We? In the first half of the 20th century, an expanding industrial city meant that railway lands divided the Downtown from a waterfront devoted to port uses. The arrival of the automobile and, by mid-century, the building of expressways propelled an era of suburbanization. A flight to the suburbs saw many Torontonians seeking quality of life away from the Central Business District, in their own front and back yards and in low-density neighbourhood parks. By the mid-1970s, City Council had adopted the Central Area Plan. One of its key ideas was the encouragement of residential uses alongside commerce in the Downtown, a first in North America. This led to a reversal of Downtown population decline and helped Toronto avoid the inner-city deterioration experienced in many other cities across the continent. Strong planning policies together with public and private investments set the stage for the expansion of housing, the growth of the Financial District, rapid transit expansion and waterfront regeneration. -

Tocore Downtown Parks – Phase 1 Background Report

DOWNTOWN PARKS TOcore PHASE I BACKGROUND REPORT MARCH 2016 PARKS, FORESTRY & RECREATION DOWNTOWN PARKS PHASE I BACKGROUND REPORT 1 DOWNTOWN PARKS PHASE I BACKGROUND REPORT CONTENTS Preface -page 1 1. Toronto’s Downtown Parks -page 3 2. Parks Planning and Development Challenges and Opportunities -page 8 2.1. Acquisition and Provision -page 8 2.2. Design and Build -page 12 2.3. Maintenance and Operations -page 13 3. Downtown Park User Opinions and Behaviour -page 14 3.1. Parks Asset and Use Survey, Summer 2015 -page 14 3.2. Park User Surveys -page 16 3.3. Park Permit Trends Downtown -page 17 3.4. TOcore Phase I Consultation -page 18 3.5. Dogs in Parks -page 18 3.6. Homelessness in Parks -page 18 4. A Healthy Urban Forest -page 19 5. Emerging Priorities -page 20 TOcore Downtown Parks -page 21 DOWNTOWN PARKS TOcore PHASE I BACKGROUND REPORT Parks are essential to making Toronto an attractive place to live, work, and visit. Toronto’s parks offer a broad range of outdoor leisure and recreation opportunities, transportation routes, and places for residents to interact with nature, and with one another. Parks also provide important economic benefits: they attract tourists and businesses, and help to build a healthy workforce. They provide shade, produce oxygen, and store stormwater. Parks are necessary elements for healthy individuals, communities, and natural habitat. Toronto Parks Plan 2013-2017 Figure 1. HTO Park in the summer Together with City Planning Division and Transportation Services Division, Parks, Forestry & Recreation Division (PFR) are developing a Downtown Parks and Public Realm (P+PR) Plan as part of the TOcore study (www.toronto. -

Lower Don Trail Suggested Routes Accessible Trail Entry Point Trail

To Edwards Gardens & Toronto Botanical Garden West Don River Don Valley Pkwy Sunnybrook Park E Eglinton Ave. E. Eglinton Ave. E. Sutherland Dr. Sutherland Bayview Ave. Bayview Beltline Trail Linkwood Lane Park Davisville Ave. East Don River Millwood Rd. Mt. Pleasant E.T. Seton Redway Rd. Cemetery Park Moore Ave. Bayview Ave. Yonge St. Crothers Woods Beltline Trail Taylor Massey Creek Mt. Pleasant Rd. Pleasant Mt. Taylor Creek Trail Don Valley Pkwy O’Connor Dr. Pottery Rd. Cosburn Ave. Roxborough Dr. Todmorden Mills Mortimer Ave. Crescent Rd. y w k P Mt. Pleasant Rd. Pleasant Mt. y ilkma e South Dr. M n’s L l n. l a V Craigleigh n o Gardens D Broadview Ave. Park Rd. Rosedale Valley Rd. F Bayview Ave. Bayview Danforth Ave. Bloor St. W. G Bloor St. E. Queen’s Wellesley St. E. Park Wellesley St. E. Riverdale Amelia St. Park East Riverdale Winchester St. Farm D Langley Ave. Carlton St. Greenwood Ave. Greenwood Gerrard St. E. Gerrard St. E. Dundas St. E. River St. River Parliament St. Parliament Sherbourne St. Sherbourne Dundas St. E. Woodbine Ave. Woodbine Shuter St. Broadview Ave. Broadview Yonge St. Yonge Bayview Ave. Bayview Queen St. E. Queen St. W. Woodbine Knox Ave. Knox Park Sarah Ashbridge Ave. Ashbridge Sarah Northern Dancer Blvd. Dancer Northern A Eastern Ave. Corktown B Common King St. W. Front St. E. Don Woodbine Landing Lake Shore Blvd. E. Beach Mill St. Distillery Front St. W. C District UNION STATION Entertainment Gardiner Expy District Queens Quay E. Port Lands Cherry St. Cherry Cherry 0 0.5 1 km Beach A From Corktown Common to Evergreen Brick Works (Approx. -

David Crombie Revitalization Project Public Workshop Powerpoint

David Crombie Park Revitalization Design Workshop #1 November 29, 2018 1 Today’s Presentation 1 Our Team 2 Overview & Work Program 3 History & Context 4 Analysis 5 Examples of Great Parks 6 David Crombie Park Is… 7 Workshop Activities 2 The Team The Planning Partnership Project Lead, Landscape Architects and Public Consultation 880 Cities Public Life Study And technical support in engineering, lighting and design of play structures Regent Park Lee Lifeson Art Park 3 Internal Stakeholders • Parks, Forestry & Recreation • Transportation Services • St Lawrence Community Recreation Centre 4 Key External Stakeholders 3 Schools (TDSB and TCDSB) St Lawrence Neighbourhood Association BIA TCHC 5 David Crombie Park Revitalization Design The David Crombie Park Revitalization Design project will develop a comprehensive conceptual design and implementation plan for improvements to the park that meet the current and future needs of the community. The design will evolve through consultation with residents, the public and other stakeholders. 6 Overview of Work Program Stage 1 Stage 2 Background Review, Site Revitalization Design Inventory & Analysis Concept Options Fall 2018 Winter 2019 Stage 3 Stage 4 Final Park Revitalization Master Plan Design & Implementation Plan Recommendations Spring 2019 Fall 2019 Consultation Summary 8 Consultation – Stage 1 Community Resource Group Meeting July 27, 2018 Public Life Study August 15 and 25, 2018 325 Surveys October 25 and November 3 One-on-One Interviews 40 Interviews September 18, 2018 Conducted Public Kick-off Event 160 Registered November 20, 2018 Participants Public Workshop November 29, 2018 3:00 pm and 6:30 pm 9 Flyer Postcard 10 Flyer 8000 Flyers were mailed out 11 Kick-off Event • Moderated by Jane Farrow, an author and former CBC broadcaster • David Crombie, the namesake of the Park and mayor when the St.