ENT EXPERT QUESTIONS

Otic Disorders

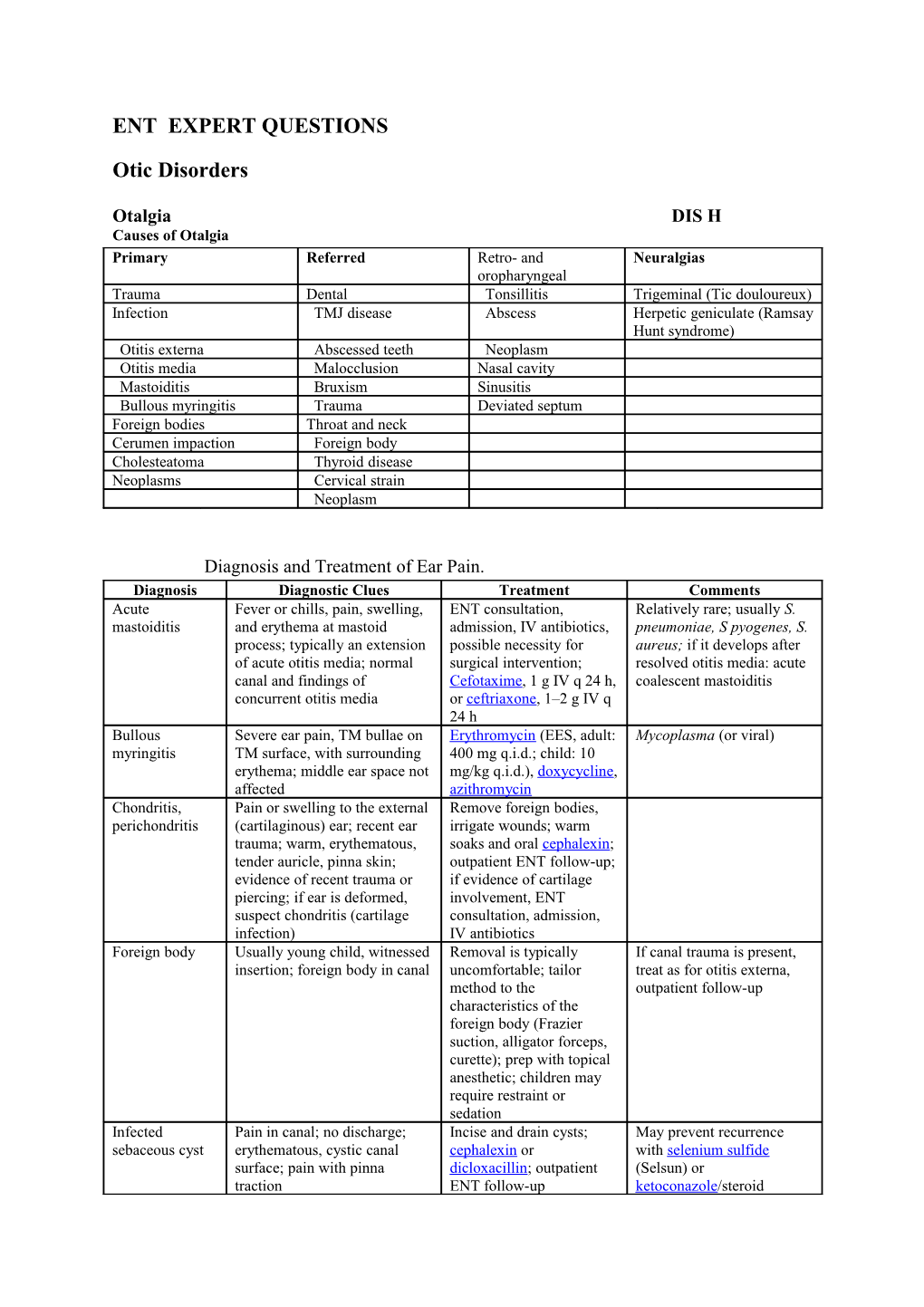

Otalgia DIS H Causes of Otalgia Primary Referred Retro- and Neuralgias oropharyngeal Trauma Dental Tonsillitis Trigeminal (Tic douloureux) Infection TMJ disease Abscess Herpetic geniculate (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) Otitis externa Abscessed teeth Neoplasm Otitis media Malocclusion Nasal cavity Mastoiditis Bruxism Sinusitis Bullous myringitis Trauma Deviated septum Foreign bodies Throat and neck Cerumen impaction Foreign body Cholesteatoma Thyroid disease Neoplasms Cervical strain Neoplasm

Diagnosis and Treatment of Ear Pain. Diagnosis Diagnostic Clues Treatment Comments Acute Fever or chills, pain, swelling, ENT consultation, Relatively rare; usually S. mastoiditis and erythema at mastoid admission, IV antibiotics, pneumoniae, S pyogenes, S. process; typically an extension possible necessity for aureus; if it develops after of acute otitis media; normal surgical intervention; resolved otitis media: acute canal and findings of Cefotaxime, 1 g IV q 24 h, coalescent mastoiditis concurrent otitis media or ceftriaxone, 1–2 g IV q 24 h Bullous Severe ear pain, TM bullae on Erythromycin (EES, adult: Mycoplasma (or viral) myringitis TM surface, with surrounding 400 mg q.i.d.; child: 10 erythema; middle ear space not mg/kg q.i.d.), doxycycline, affected azithromycin Chondritis, Pain or swelling to the external Remove foreign bodies, perichondritis (cartilaginous) ear; recent ear irrigate wounds; warm trauma; warm, erythematous, soaks and oral cephalexin; tender auricle, pinna skin; outpatient ENT follow-up; evidence of recent trauma or if evidence of cartilage piercing; if ear is deformed, involvement, ENT suspect chondritis (cartilage consultation, admission, infection) IV antibiotics Foreign body Usually young child, witnessed Removal is typically If canal trauma is present, insertion; foreign body in canal uncomfortable; tailor treat as for otitis externa, method to the outpatient follow-up characteristics of the foreign body (Frazier suction, alligator forceps, curette); prep with topical anesthetic; children may require restraint or sedation Infected Pain in canal; no discharge; Incise and drain cysts; May prevent recurrence sebaceous cyst erythematous, cystic canal cephalexin or with selenium sulfide surface; pain with pinna dicloxacillin; outpatient (Selsun) or traction ENT follow-up ketoconazole/steroid shampoo Insect in canal Buzzing or movement Immobilization will Alternatively, may remove a sensation; insect in canal or on relieve the discomfort; large insect with narrow TM catheter; flush out when instill lidocaine in the alligator forceps through the patient is calm canal with a syringe and otoscope flexible Otitis externa Common in regular swimmers; Place a cotton wick Typically Pseudomonas; (swimmer's ear) ear pain, itching. Purulent through an obstructed or outpatient follow-up within discharge, erythematous canal, near-obstructed canal; treat 3 days; reduce recurrence pain with pinna traction; canal with topical steroid and risk with drying rubbing may be occluded by wall antibiotic preparations: alcohol drops following edema; normal hearing unless hydrocortisone-polymyxin water exposure; consider canal is occluded neomycin (Cortisporin malignant variant in Otic), 4 drops q.i.d., or diabetic, hydrocortisone- immunocompromised, or ciprofloxacin (Cipro HC elderly patients Otic), 3 drops b.i.d. Otitis externa Elderly, immunocompromised, ENT consultation, Pseudomonas can cause (malignant) or diabetic patient with admission, IV antibiotics rapidly progressing, findings of otitis externa; (imipenem-cilastatin, 500 necrotizing disease among physical findings as above mg IV q 6 h; vulnerable patients; ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV outpatient treatment may be q 12 h or 750 mg PO q 12 acceptable in early disease; h) CT scan if mastoid osteomyelitis is suspected Serous/secretory Preceding upper respiratory Decongestant for 14 days Not infectious; relates to otitis media infection or otitis media; eustachian canal unilateral hearing loss, pain, obstruction; obtain ENT pressure, or bubbling sound (all evaluation if it does not of variable severity); normal resolve in 2 weeks; some canal; TM not erythematous, clinicians rous (mobile but decreased motility and light fluid) from secretory (thick, reflex; landmarks visible; air– nonmotile fluid) otitis, but fluid levels behind TM treatment is the same Suppurative Common in children; preceding Amoxicillin (adults: 500 Typical organisms: S. otitis media upper respiratory infection; mg t.i.d. x 10 d; children: pneumonia, H. influenzae may lead to TM rupture (severe 15 mg/kg t.i.d. x10 d); if (children); ruptured TM will pain followed by rapid, child has had abscess in require follow-up every 2–4 spontaneous relief); normal past month, high-dose weeks to ensure healing canal; TM is erythematous, dull amoxicillin (30 mg/kg light reflex, limited motility t.i.d. x10 d); if recent (most specific), landmarks not treatment failure, visible; compare to other side; amoxicillin–clavulanate make note of TM rupture, if (Augmentin, 25–30 mg/kg present; decreased hearing on t.i.d. x 10 d); other affected side options, trimethoprim– sulfamethoxazole, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone History Ask patients about history of trauma, surgery, or recurrent infections involving the ear. Also ask about specific symptoms (e.g., recent fever, upper respiratory infection, or canal discharge) and pain quality (e.g., pain, pressure, itching, or "buzzing" sounds). Have the patient identify the exact location of the pain. A narrow differential diagnosis can be explored based on these historical characteristics. Physical Examination Palpate the area surrounding the ear to identify lymph nodes or a bony prominence. Tender nodes are common in infections of the middle and external ear. Pain, swelling, and erythema at the mastoid process should prompt the clinician to consider mastoiditis. If the pain relates to the canal, examine its external orifice for evidence of discharge. Next, view the canal and tympanic membrane. Make careful note of the appearance of the tympanic membrane regarding color, reflectivity, visibility of landmarks, and presence of fluid, air bubbles behind the membrane, or perforations. Check tympanic membrane motility by insufflation. Compare to the normal ear. If the ear examination is normal, look to the upper teeth and temporomandibular joint as possible causes.

Otitis media DIS H Otitis media (OM) is primarily a disease of infancy and childhood. Although adults may present with OM, its incidence and prevalence peak in the preschool years and then decrease with increasing age. There is little or no literature to suggest that the diagnosis or management of OM in adults differs from that in children. The decrease in incidence of OM from childhood through adolescence is thought to be due to the changing anatomy of the eustachian tube. Between infancy and adulthood the eustachian tube angle and length both increase, promoting drainage of the middle ear and offering a greater physical barrier to the migration of bacteria from the nasopharynx to the middle ear. Etiology The most common bacterial pathogens in acute OM are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. The predominant organisms involved in chronic OM are Staphylococcus aureus, P. aeruginosa, and anaerobic bacteria. This pattern may change, however, with increasing use of pneumococcal vaccines. The heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine recently approved for use in the United States may provide protection against S. pneumoniae serotypes responsible for up to 86 percent of bacterial isolates causing OM, including >95 percent of drug-resistant isolates. Viruses probably play a role in the pathogenesis of OM in that they may promote bacterial superinfection by impairing eustachian tube function and other host defense mechanisms.

Diagnosis

The patient with OM presents with otalgia with or without fever. Otorrhea and hearing loss are variably present, while tinnitus, vertigo, and nystagmus are uncommon. The TM may be retracted or bulging. It may be red in color, indicating inflammation, or it may be yellow or white, as a result of middle ear fluid. Pneumatic otoscopy demonstrates impaired mobility.

The facial nerve should always be assessed because of its proximity to the middle ear.

Treatment See table above for treatment – usually amoxicillin first line, augmentin second line or treatment failures. Otitis externa DIS H Otitis externa includes infections and inflammation of the EAC and auricle. It is divided into acute diffuse and malignant types. Acute Diffuse Otitis Externa Also known simply as otitis externa (OE) or swimmer's ear, this infection is characterized by pruritus, pain, and tenderness of the external ear. Physical signs Physical signs include erythema and edema of the EAC, which may spread to the tragus and auricle. Other signs are clear or purulent otorrhea and crusting of the EAC. As the disease progresses, the pain may become intolerable and occur with mastication or any movement of the periauricular skin. Increasing edema eventually narrows the EAC lumen and may cause hearing impairment. In severe cases, infection may spread to the periauricular soft tissues and lymph nodes, and there may be lateral protrusion of the auricle secondary to inflammation. Pathophysiology Predisposing factors for the development of OE are trauma to the skin of the EAC and elevation of the local pH. Constant contact with water, from swimming or bathing in hot tubs, pools, or freshwater lakes is associated with the development of OE, as is living in a humid environment. Trauma is most commonly caused by scratching or by overzealous disimpaction of cerumen. Cerumen is an acidic mixture of sebaceous and apocrine gland secretions and desquamated epithelial cells. It forms a physical barrier that protects the EAC skin from violation, while the acidic pH has antimicrobial properties. Microbiology The most common organisms implicated in OE are Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus or polymicrobial as found in some other studies. Otomycosis, or fungal OE, accounts for approximately 10 percent of cases, with a high percentage found in tropical climates. A history may reveal the presence of diabetes, HIV, or other immunocompromised states, or previous long-term therapy with antibiotics. Most (80 to 90 percent) of otomycosis is caused by Aspergillus species, and physical examination may reveal a black, blue-green, or yellow discoloration of the EAC. The second most common fungal pathogen is Candida Noninfectious causes include contact dermatitis from topical medications or resins in hearing aids, seborrhea, and psoriasis. Treatment The treatment of OE involves analgesia, cleansing of the EAC, acidifying agents, topical antimicrobials, and sometimes steroids. Cleansing may be done with gentle irrigation using hydrogen peroxide, and gentle debridement by the physician with a suction aspirator such as a Frazier suction. Refer to table for local otic preparations listed to be used.

Malignant Otitis Externa

Malignant otitis externa (MOE) is a potentially life-threatening infection of the EAC with variable extension to the skull base. It is almost always caused by P. aeruginosa. The term MOE actually refers to a spectrum of disease. When it is limited to the soft tissues and cartilage, it is called necrotizing otitis externa (NOE). When there is involvement of the temporal bone or skull base it is called skull-base osteomyelitis (SBO). Pathophysiology MOE begins as a simple otitis externa that then spreads to the deeper tissues of the EAC and infects cartilage, periosteum, and bone, with the normal anatomy of the ear serving as the conduit for the spread of infection. The cartilaginous floor of the EAC has clefts, known as the fissures of Santorini, through which the infection may spread to deeper structures. The parotid gland and TMJ are anterior, The mastoid air cells are posterior, and The skull base, carotid artery, jugular bulb, and sigmoid sinus are inferomedial. Infection may spread to any of these structures as well as to the seventh cranial nerve as it exits the stylomastoid foramen and The ninth, tenth, and eleventh cranial nerves at the jugular foramen. Microbiology The most common causative organism of MOE is P. aeruginosa. Aspergillus has been reported to cause SBO, usually in patients who are immunosuppressed because of AIDS or other causes. Aspergillus SBO also has a different presentation than typical pseudomonal SBO in that the infection generally begins in the middle ear rather than in the EAC. Diagnosis Any elderly, diabetic, HIV, or otherwise immunocompromised patient presenting with OE or any person with persistent OE despite 2 to 3 weeks of topical antimicrobial therapy should be suspected of having MOE. The typical presentation is similar to that of OE: otalgia and edema of the EAC with or without otorrhea. The otalgia may be out of proportion for routine OE. Granulation tissue may be evident on the floor of the EAC near the bone-cartilage junction. The history and physical examination should also be directed toward determining the extent of progression of the disease by identifying involvement of nearby structures. Parotitis may be present, and trismus indicates involvement of the masseter muscle or TMJ. Cranial nerve involvement is a serious sign. The history and examination should specifically rule out facial palsy and hoarseness or dysphagia. The seventh cranial nerve is usually the first affected, and the presence of dysfunction of the ninth, tenth, or eleventh cranial nerve implies even more extensive disease. Lateral or sigmoid sinus thrombosis and meningitis are also possible complications. Diagnosing MOE depends first on having a high index of suspicion. Emergent otolaryngologic consultation is necessary. The next step involves radiographic confirmation and staging of the disease with computed tomography (CT) of the head, focusing on the EAC and temporal bone. Treatment Once the diagnosis of MOE has been made, the patient should be admitted to the hospital for parenteral antibiotics. Therapy with an aminoglycoside and antipseudomonal penicillin, or cephalosporin, or quinolone is standard, and should be initiated in the ED. The ultimate prognosis of MOE is primarily based on the stage of disease at presentation. Earlier stages are likely to completely resolve with a single course of antibiotic therapy, while more advanced stages may require surgical debridement and may ultimately prove fatal. Perforated tympanic membrane DIS H Etiology: Direct trauma: Cotton tip applicator Pins Pencils Flying objects at work e.g. welding hot metal slag Barotrauma: Slap to the ear Blast injury Rapid descent in aircraft Clinical features: patients usually complain of pain and hearing loss, and the perforation can be diagnosed by otoscopy Always important to assess patients for evidence of other injuries esp in case of trauma or blast injuries Examination: It is important to note how much of the tympanic membrane has been perforated. A central perforation does not involve the annulus of the eardrum, whereas a marginal perforation does. The Weber tuning fork test should be performed to verify that it radiates to the affected ear, and the eyes should be checked for nystagmus. If the Weber test does not radiate to the affected ear and the patient has nystagmus, it is likely that stapes subluxation with sensorineural hearing loss has occurred. This is termed a perilymphatic fistula and requires urgent treatment Management: If no evidence of sensorineural hearing loss is found, no specific treatment is required because traumatic tympanic membrane perforations, especially central perforations, typically heal spontaneously. However, strict dry ear precautions should be followed to prevent water from getting into the ear. Instructions to the patient include no swimming and the use of a cotton ball thoroughly coated with petrolatum (eg, Vaseline) in the affected ear during bathing. An audiogram should be performed after about 3 months to verify that hearing has returned to normal and that there is no ossicular chain discontinuity. If the perforation has not healed by 3 months, a tympanoplasty will likely need to be performed.

Mastoditis DIS H

The fact that the mastoid air cell system is part of the middle ear cleft means that some degree of mastoid inflammation occurs whenever there is infection in the middle ear. In most cases, this infection does not progress to clinically apparent acute mastoiditis. However, if pus collects in the mastoid air cells under pressure, necrosis of the bony trabeculae occurs, resulting in the formation of an abscess cavity. The infection may then progress to periostitis and subperiosteal abscess, or to a more serious intracranial infection. Acute Mastoiditis Typically, acute mastoiditis presents as a complication of AOM in a child. Clinical features Pain and tenderness over the mastoid process are the initial indicators of mastoiditis. As the infection progresses, edema and erythema of the postauricular soft tissues with loss of the postauricular crease develop. These changes result in anteroinferior displacement of the pinna. Fullness of the posterior wall of the external auditory canal is frequently seen on otoscopy as a result of the underlying osteitis. If a subperiosteal abscess has developed, fluctuance may be elicited in the postauricular area. Rarely, a mastoid abscess can extend into the neck (Bezold's abscess) or the occipital bone (Citelli abscess). Diagnosis Once the diagnosis of acute mastoiditis is suspected, the radiologic investigation of choice is a CT scan, which provides information about the extent of the opacification of the mastoid air cells, the formation of subperiosteal abscess, and the presence of intracranial complications. Management In some cases, acute mastoiditis can be successfully managed by antibiotic therapy alone, but some patients require surgical intervention. When there is no clinical or radiologic indication of a subperiosteal abscess or an intracranial extension of disease, then high-dose broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be commenced. If, after 24 hours of treatment, there is no evidence of resolution or if symptoms progress, a cortical mastoidectomy should be performed, along with myringotomy if spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane has not occurred. If a subperiosteal abscess or an intracranial extension of disease is suspected, surgery in combination with high-dose intravenous antibiotics should be the first-line therapy.

Labyrinthitis DIS H

Labyrinthitis is an infection of the labyrinth that produces peripheral vertigo associated with hearing loss. The infection may be viral, in which case the clinical course is similar to that of vestibular neuronitis. Cases reportedly have been associated with measles and mumps. Bacteria also may cause labyrinthitis. Although unusual, an infection within the labyrinth can develop from otitis media, in which bacteria and toxins diffuse across the membrane of the round window. A cholesteatoma can erode into the inner ear, creating a portal of entry for bacteria. Other possible antecedents for bacterial labyrinthitis include otitis media with fistula, meningitis, mastoiditis, and dermoid tumor. The hallmarks of this disease include sudden onset of vertigo with associated hearing loss and middle ear findings. Serous labyrinthitis occasionally may produce vertigo.

Patients with bacterial labyrinthitis may benefit from symptomatic treatment but also require antibiotics and referral to an otologist or ENT specialist for likely admission and possible surgical drainage. Nasal Disorders Epistaxis Anterior packing DIS H Cautery DIS H Posterior packing DIS H Balloon placement DIS H

Nasal hemorrhage commonly presents to the ED and accounts for about 1 in 200 ED visits. Epistaxis is more common in the young (<10 yr) and old (70–79 yr). Most cases are traumatic and occur in winter months. Approximately 6% require hospitalization. Identification of the source of bleeding and subsequent control is paramount to the treatment of epistaxis. History In preparation for any procedure to treat epistaxis, evaluate the patient's hemodynamic status by assessing vital signs and orthostatic symptoms and by quantifying blood loss. Also determine whether the patient has any underlying medical problems, such as angina or chronic obstructive lung disease, which may be exacerbated owing to hypovolemia or anemia. Supportive management If the patient is symptomatic in any of these areas, or if the blood loss is deemed significant, start a large-bore intravenous line and administer fluid boluses. Many patients with epistaxis are hypertensive as well, often transiently secondary to stress. No direct causal correlation between hypertension and overt epistaxis has been proved. Hypertension is probably a stress response instead of an inciting event.[38] Therefore, hypertension does not require treatment until the bleeding is controlled and the anxiety of the situation has resolved. However, any patient exhibiting other signs of a hypertensive emergency needs immediate treatment in addition to control of the epistaxis. Investigations Hematologic testing is rarely useful and not required for most patients, but if there are extenuating circumstances, obtain a complete blood count and consider a type and screen. Coagulation studies are not routinely indicated but should be undertaken in patients taking anticoagulant therapy, those with underlying hematologic abnormalities, or those with recurrent or prolonged epistaxis. Indications for packing: Any cause of epistaxis causing significant symptoms will indicate the need for intervention Contraindications: Facial trauma with possibility of basilar skull fracture would preclude the use of an intranasal balloon due to risk of migration into cranial cavity. Epistaxis Examination: Reassurance to reduce anxiety Judicious use of sedation or narcotic analgesia Drape patient and emesis basin for patient Universal precaution for physician including face mask and goggles Clear out nasal passage by either blowing or by suctioning If poor visuality, try topical anesthetic and vasoconstrictor preparations e.g. 4% cocaine or 4% lidocaine Ask patient to clamp nostril to limit bleeding and promote contact with mucosa Inject base f bleeder with 2% lidocaine + adrenaline Inspect area of Kiesselbach’s plexus for areas of bleeding, ulceration or erosion. Cautery: Hold silver nitrate stick or electrical cautery on localized area for 4-5 seconds Will not work if active bleeding ongoing Avoid aggressive cautery, repeated cautery and bilateral cautery due to risk of perforation; maximum two attempts in one sitting If cautery unsuccessful apply anterior nasal pack Avoid aspirin, NSAIDs for 4-5 days if feasible If hemostasis achieved apply petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment to area to avoid dessication Instruct patient to pinch nostrils closed for 20 minutes if bleeding recurs at home and return to ED if maneuver unsuccessful or bleeding profuse Anterior nasal packing: Anterior packing achieves hemostasis, prevents desiccation, and protects the area from trauma. However, improperly placed packing may further abrade the area, dislodge prematurely, or migrate into the posterior pharynx. Anterior packing must be placed with adequate analgesia, proper visualization, and deliberate movements. Coating any packing material with antibiotic ointment (if not contraindicated by the manufacturer) aids in its placement and theoretically prevents infection and toxic shock syndrome secondary to nasal packing. Areas that continue to ooze after cautery are often treated with an anterior pack. Compared with gauze packing, numerous compression devices are easier to place, better tolerated, and very successful. Preformed nasal packing products are convenient alternatives to anterior nasal packing. The easily applied nasal tampon is a reasonable first choice for most anterior bleeds. Lubricate the tampon generously with antibiotic ointment and trim the length and width carefully to minimize trauma to the nose. Using bayonet forceps, advance the packing carefully along the floor of the nose. Remember to direct it parallel to the floor, not upward toward the top of the nose. The insertion may be painful, so use a single rapid movement. Once the packing is in the nasal cavity, expand it with 5 to 10 mL of saline, although contact with the moisture of the nose will often cause it to swell spontaneously. Observe for 10 minutes after anterior packing to identify continued bleeding either anteriorly from the naris or running down the posterior pharynx. Anterior packs are usually left in for 2 to 5 days. Premature removal may result in rebleeding. During use and before removal, keep the nasal tampon hydrated with saline. If it contains an airway tube, first remove the tube, then irrigate the space once occupied by the tube. Advantages to the Merocel tampon include rapid insertion, little discomfort, ease of use even in inexperienced hands, and possible inhibition of bacterial growth. Complications May obstruct drainage of the paranasal sinuses or block the nasolacrimal ducts. A pack or device may stimulate mucus production and act as an impetus for infection. Oral antibiotics (e.g., cephalexin, amoxicillin, or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) may be prescribed with any packing in the nose after emergency treatment because of the minimal risk of sinusitis and toxic shock syndrome. There have been case reports of ethmoid fracture after anterior nasal gauze packing and with the use of an intranasal balloon. Disposition: Patients with anterior packs are usually discharged with follow-up as outpatients in 3 to 4 days. Minor oozing of blood can be expected.

Posterior Nasal Packing If no bleeding source is found anteriorly and the patient continues to hemorrhage down the posterior pharynx, the patient most likely has a posterior source of epistaxis. Posterior epistaxis may respond to topical vasoconstrictors. However, anterior nasal packing will not provide hemostasis for a posterior bleed because it will not cover the source of bleeding. A posterior pack directly compresses the sphenopalatine artery and prevents the passage of blood or anterior packing into the nasopharynx. The posterior nasal gauze pack is the classic method of treating posterior epistaxis. However, because balloon devices are easier to use and less distressing to the patient, formal posterior nasal packing is less commonly used. Inflatable balloons come in two varieties. The Foley catheter is often used as a posterior pack because of its availability, ease of use, and successful tamponading effect. Insert a 12-French Foley catheter through the bleeding naris into the posterior pharynx. Inflate the balloon halfway with about 5 to 7 mL of normal saline or water. Slowly pull the Foley into the posterior nasopharynx and secure it against the posterior aspect of the middle turbinate. Finish inflating the balloon with another 5 to 7 mL of normal saline or water. If there is pain or inferior displacement of the soft palate, deflate the balloon until the pain resolves. While maintaining constant gentle anterior tension on the Foley catheter, place an anterior nasal packing using layered petroleum gauze. Pack the opposite nasal cavity to counteract septal deviation. Finally, place a short section of plastic tubing over the catheter and secure it with a nasogastric tube clamp or umbilical clamp. Be careful not to exert undue pressure on the nasal alar because this may cause necrosis. Premade posterior nasal packs The second type of inflatable balloon pack is the premade dual-balloon tamponading system. These devices have been a significant advance in the treatment of epistaxis. Several balloon devices are available. The dual-balloon pack has a posterior balloon that inflates with about 10 mL of air and an anterior balloon that inflates with about 30 mL of air. Inflate slowly, and stop if pain is felt. This is usually an uncomfortable sensation to the patient. If the patient complains of pain or if the posterior soft palate deviates downward, deflate the balloon until the symptoms are relieved. Maintain the position of the balloon and inflate the anterior balloon with up to 30 mL of air. Again, halt inflation if the patient experiences increasing pain or deviation of the nasal septum. Place a small piece of gauze between the nose and the external catheter hub to decrease skin irritation. Complications Care of posterior nasal packing is of some concern. Posterior nasal packing is uncomfortable and often painful. These bleeds are more complicated than simple anterior septal bleeds. Complications associated with posterior packing include Infection - toxic shock syndrome, nasopharyngitis, and sinusitis, dysphagia, eustachian tube dysfunction, tissue necrosis - nasal ala, nasal mucosa, and soft palate, and dislodgment. Other serious complications rarely associated with posterior packing are hypoxia, hypercarbia, aspiration, hypertension, bradycardia, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, and death. Disposition: For these reasons, most patients with a posterior pack, especially the elderly and those with pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases, should be admitted to the hospital for sedation and monitoring. Rebleeding may also be seen with early pack removal; Most posterior packs are left in place for 72 to 96 hours. In addition to coating the packing with antibiotic ointment, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. Dysphagia due to the packing can lead to poor oral intake, and intravenous fluid hydration may be required. Nasal Foreign Bodies Children frequently insert foreign bodies that may require removal into their nares. Items placed in the nasal cavity are limited only by the child's imagination, and are most often food, paper, and pieces of toys. Dried beans and vegetable matter are particularly concerning because they tend to absorb fluid and swell, increasing discomfort and making removal difficult. Other common foreign bodies include rocks, buttons, and small batteries.

In most cases, the insertion of the foreign body is actually observed by the caregiver, or the child reports the presence of a foreign body. Suspect a nasal foreign body in the following circumstances:

1. Sensation of unilateral nasal obstruction 2. Persistent, foul-smelling rhinorrhea despite proper antibiotic treatment 3. Persistent unilateral epistaxis

In addition to a nasal examination, a complete head and neck physical examination is performed. The ears are also carefully checked for foreign bodies, and the lungs auscultated for wheezing.

Treatment

If the child is cooperative and the foreign body visible, it is possible to remove the object in the ED. In small or uncooperative children, a papoose board may be used for restraint. The nasal mucosa is generally prepared with vasoconstrictors and anesthetics (1 mL of phenylephrine mixed with 3 mL of 4 percent xylocaine). In uncooperative children, aerosolized adrenaline (racemic epinephrine) can be used to decongest the nasal mucosa and loosen the foreign body. When administered in the aerosolized form by the parent, it causes little or no distress to the child. Following this, visualization with an appropriate-sized nasal speculum is attempted.

If the object appears loose after vasoconstriction, an attempt to remove it can be made using a number of different techniques including:

1. Positive pressure technique 2. Removal by a suction catheter 3. Grasping the object with bayonet or alligator forceps 4. Passing a curette beyond the object, rotating the instrument, and pulling the foreign body out 5. Passing a Fogarty vascular catheter past the foreign body, inflating the balloon, and removing the catheter and foreign body

The latter four techniques are all acceptable, but require a cooperative child, physical restraint, or conscious sedation to prevent damage to the nasal mucosa. Regardless of the technique utilized, the airway must be protected and appropriate material for managing airway obstruction should be immediately available. The examiner should be careful not to advance the foreign body deeper into the nasopharynx. Sinusitis

Pathophysiology There are six nasal sinuses: two maxillary, two frontal, one sphenoidal, and the ethmoidal air cells. Sinusitis occurs when there is an acute obstruction of the normal drainage mechanisms of the sinuses. Efficiency of sinus drainage consists of three elements: ostial patency, ciliary apparatus function, and the quality of the nasal secretions. Inflammatory edema causes obstruction or mucociliary drainage at the osteomeatal complex, followed by reabsorption of the air in the sinus, resulting in negative pressure. Negative pressure causes a collection of transudate within the sinus cavity. If bacteria are present, suppuration results. Microbiology Acute sinusitis is acute inflammation of the paranasal sinuses of less than 3 weeks duration. Viral upper respiratory tract infections and allergic rhinitis are the most common initiating factors in acute sinusitis. Bacterial sinusitis is most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Immunocompromised patients may be infected with the usual pathogens, opportunistic bacteria, or fungi. Chronic sinusitis results from unresolved acute sinusitis of more than 3 weeks duration. In chronic sinusitis, polymicrobial anaerobic species are found in most cases. Clinical Features The consensus definition of acute bacterial sinusitis is as follows: 1. symptoms for 7 days or more; 2. sinus pain or tenderness in the face or teeth; and 3. purulent nasal secretions. Ethmoidal sinusitis usually causes a dull, aching sensation behind the eye. Infection of the frontal and maxillary sinuses generally causes pain over the affected sinus. Ethmoidal sinusitis can spread to the orbit, retro-orbital area, and central nervous system. The headache of sinusitis may be aggravated by bending forward, coughing, or sneezing. On physical examination, there may be tenderness to palpation and percussion over the involved sinus, and direct visualization of the nasal cavity may show swollen, erythematous mucosa with purulent exudate draining from the ostia. Diminished transillumination of the affected sinus can also be seen. Diagnosis Radiography is not recommended for diagnosis in routine cases. The radiographic signs of sinusitis are sinus opacity or fluid, with a sensitivity of 0.73 and specificity of 0.80 for radiography when compared to sinus puncture/aspiration as the gold standard. Computed tomography (CT) has a greater ability to define physical characteristics, but its primary role is to diagnose sinusitis when the differential diagnosis is unclear and to define anatomy before surgery. Complications: The most important points to consider are those diagnoses arising as complications from sinusitis. These include any evidence of infectious extension from the sinus cavity, such as: periorbital cellulitis, brain abscess, subdural empyema, meningitis, or cavernous sinus thrombosis. Differential diagnosis: Include the complications of sinusitis and patients with signs and symptoms of facial pain: tension headache, migraines, and cluster headache dental pain and rhinitis. Treatment: For acute sinusitis with mild symptoms of less than 7 days' duration, symptomatic treatment is recommended. Antimicrobial therapy shortens the symptomatic period by several days and decreases the incidence of respiratory complications. The most cost-effective initial antibiotic choices are amoxicillin or trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, Cefuroxime or azithromycin. In patients with suspected streptococcal antibiotic resistance, then amoxicillin-clavulanate, or a "respiratory" fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) can be considered In chronic sinusitis, recommended antibiotics include amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime, moxifloxacin, or clindamycin. Over-the-counter nasal spray decongestants or antihistamines such as pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, or oxymetazoline, are commonly used to alleviate symptoms of sinusitis. Steroid nasal sprays, used twice daily, can improve symptoms of acute sinusitis compared to antibiotic treatment alone. Disposition Most patients with acute sinusitis can be treated as outpatients. Hospitalization is required if there is evidence of infectious spread beyond the sinus cavity, or if there is systemic toxicity. Discharged patients should receive follow-up in 5 to 7 days, with instructions to return to the ED for persistent fever, severe or worsening headache, visual changes, or vomiting. GABHS Pharyngitis Streptococcus pyogenes (GABHS) is responsible for 5 to 15 percent of pharyngitis in adults. Virulent strains of GABHS are associated with acute rheumatic fever (ARF) or acute glomerulonephritis. Because of these sequelae, as well as local complications of untreated infection such as peritonsillar abscess, early diagnosis and treatment are important. Clinical Features After an incubation period of 2 to 5 days, patients develop the sudden onset of sore throat, painful swallowing, chills, and fever. Headache, nausea, and vomiting are common associated symptoms. Signs and symptoms of GABHS pharyngitis include marked erythema of the tonsils and tonsillar pillars; tonsillar exudate; enlarged, tender anterior cervical lymph nodes; and uvular edema. Patients tend to have fever, myalgias, and malaise but not rhinorrhea. Diagnosis: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists four criteria for GABHS pharyngitis: 1) tonsillar exudate, 2) tender anterior cervical adenopathy, 3) absence of cough, and 4) history of fever. For patients with two or more criteria, three strategies can be used: 1) Test patients with two, three, or four criteria using a rapid antigen test, and limit antibiotic therapy to patients with positive test results; 2) test patients with two or three criteria using a rapid antigen test, and limit antibiotic therapy to patients with a positive test result or with all four criteria; or 3) do not use any diagnostic tests, and limit antibiotic therapy to patients with three or four criteria. Treatment: Drug resistance is a growing problem and is related directly to the overuse of antibiotics. GABHS is rarely resistant to penicillin, which remains the recommended first-line drug for this disease. Adults should receive a single intramuscular dose of 1.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G or 500 mg of penicillin VK PO twice or three times daily for 10 days. Erythromycin is the recommended alternative for penicillin-allergic patients. Close contacts and family members should be screened and treated promptly if they become symptomatic or have a positive rapid antigen test. Epiglottitis Epiglottitis can lead to rapid, unpredictable airway obstruction. It is an inflammatory condition, usually infectious, primarily of the epiglottis but often including the entire supraglottic region. Microbiology Since most children are inoculated against Haemophilus influenzae, most cases of epiglottitis are now seen in adults with a mean age of 46 years. Epiglottitis can be caused by bacteria (most commonly Haemophilus influenzae type b, Streptococcus species, Staphylococcus species), viruses, and fungi, although most frequently no organism can be isolated. Clinical features Typically present with a 1- to 2-day history of worsening dysphagia and odynophagia and dyspnea, particularly in the supine position. Symptoms include fever, tachycardia, cervical adenopathy, drooling, and pain with gentle palpation of the larynx and upper trachea. Stridor is primarily inspiratory and is softer and lower-pitched than in croup. Patients often position themselves sitting up, leaning forward, mouth open, head extended, and panting. Thick oropharyngeal secretions are commonly present, with little or no cough. Diagnosis Diagnosis is made by history, clinical examination, radiographs, and laryngoscopy. Lateral cervical soft tissue radiographs demonstrate obliteration of the vallecula, swelling of the aryepiglottic folds, edema of the prevertebral and retropharyngeal soft tissues, and ballooning of the hypopharynx. The epiglottis appears enlarged and thumb-shaped. Direct fiberoptic examination can confirm the diagnosis in adults if necessary but should be done with extreme caution to avoid sudden, unpredictable airway obstruction. Management Require immediate otolaryngologic consultation, and the emergency physician must be prepared to establish a definitive airway. Patients should never be left unattended and should be kept sitting up. Initial treatment consists of supplemental humidified oxygen, intravenous hydration, cardiac monitoring, pulse oximetry, and intravenous antibiotics. Humidification and hydration minimize crusting in the airway and can help decrease the risk for sudden airway blockage. In adults, the need for intubation usually can be determined by fiberoptic examination of the supraglottis. This is generally accomplished by awake fiberoptic intubation in the operating room, with preparations for immediate awake tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy. In cases of airway obstruction in the emergency department, endotracheal intubation must be attempted, but the physician should be prepared for a very difficult intubation secondary to the swollen, distorted anatomy. In the case of intubation failure, the last resorts for preserving the airway in adult and pediatric patients are cricothyrotomy and needle cricothyrotomy, respectively. Retropharyngeal Abscess Retropharyngeal nodes drain the adenoids, nasopharynx, and paranasal sinuses and can become infected. If this pyogenic adenitis goes untreated, a retropharyngeal abscess forms. The process occurs most commonly during the first 2 years of life. Beyond this age, retropharyngeal abscess usually results from superinfection of a penetrating injury of the posterior wall of the oropharynx. Anatomy Two major cervical lymph node chains enter the retropharyngeal space. They drain lymph not only from the nasopharynx but also the adenoids and the posterior paranasal sinuses. The retropharyngeal space is the potential space located between the posterior pharyngeal wall (more properly the buccopharyngeal fascia) and the prevertebral fascia. It extends from the base of the skull to the level of T1 or T2 in the area of the posterior mediastinum. It is the only deep neck space that extends the entire length of the neck. Clinical features In general, children with retropharyngeal abscess appear quite ill. Signs of retropharyngeal abscess include muffled voice, persistently hyperextended neck, inspiratory stridor, meningismus, and, if partial airway obstruction is present, respiratory distress and tachypnea. Ipsilateral cervical adenopathy has also been described but is not specific. Often a unilateral or bilateral retropharyngeal mass can be visualized during examination of the oropharynx. Unilateral masses are typically easier to detect than bilateral ones. Investigations Lateral neck radiography: A lateral neck radiograph should be obtained when one suspects this infection. This radiograph should be taken during inspiration with the neck extended so as to limit false-positive results. The normal prevertebral soft tissue should be no wider at the second cervical vertebra than the diameter of the vertebral body at the same level. More than 7-mm prevertebral soft tissue width at C2 and 14-mm prevertebral soft tissue width at C6 CT scan of the neck: Definitive diagnosis should be based on CT scan results whenever possible. CT scan differentiates cellulitis from abscess and helps with surgical planning by demonstrating the degree of extension that has occurred. It can also be used to clarify equivocal x-ray findings. CT's sensitivity for retropharyngeal abscess is thought to be near 100 percent. Treatment: Initial goal is airway stabilisation Retropharyngeal cellulitis and very small localized abscesses may do well with antibiotics alone. All other cases should undergo an incision and drainage procedure. These decisions should be made in consultation with an otolaryngologist. Common organisms include S. aureus, S. pyogenes, S. viridans, and beta lactamase-producing gram- negative rods such as Klebsiella. Oral anaerobes such as Peptostreptococcus species, Fusobacterium species, and Bacteroides species are also frequently seen. High dose penicillin and caphalossporins in sensitive patients are drugs of first choice. Foreign body aspiration The peak incidence of foreign body aspiration is in the 1- to 3-year-old age group. The most commonly aspirated foreign bodies fall into two groups: foods and toys. The most dangerous objects are those that are cylindrical or small, smooth, and round. Commonly aspirated foods include peanuts, sunflower seeds, raisins, grapes, hot dogs, and small sausages. Clinical features: Many patients with foreign-body aspiration may be completely asymptomatic with a normal physical exam. The majority will present with or will have previously had symptoms consistent with but not specific for foreign body aspiration. Classic dogma is that laryngotracheal foreign bodies cause stridor, whereas bronchial foreign bodies cause wheezing. The majority of patients presenting with severe immediate-onset stridor or cardiac arrest after aspiration will be found to have a laryngotracheal foreign body. Other signs and symptoms of foreign-body aspiration may include cough, history of a choking episode, history of persistent or recurrent pneumonia, apnea, pharyngeal pain, or persistent symptoms of croup or asthma remaining after adequate treatment for 5 to 7 days. Foreign-body aspiration should be considered in all children given a diagnosis of unilateral wheezing.

Diagnosis A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose this disorder. Foreign-body aspiration should always at least be considered in a young child with respiratory symptoms, regardless of the duration of symptoms, since many children may present more than 24 h after foreign body aspiration. In a stable child, plain radiographs may be helpful if positive. Plain radiographs may be entirely normal in up to one-third of foreign-body aspiration cases. Most aspirated foreign bodies are not radiopaque. In cases of complete obstruction, segmental atelectasis may be seen on plain radiographs. In other cases, intermittent or partial obstruction occurs, creating a ball-valve effect. Partial obstruction, most commonly of the right mainstem bronchus, may cause obstructive emphysema of the involved lung by allowing air past the obstruction on inhalation, but preventing its passage on exhalation. In cooperative, stable children, inspiratory and expiratory PA chest radiographs to search for hyperinflation of the involved lung with contralateral mediastinal shift and decreased excursion of the ipsilateral diaphragm may be indicated. Foreign-body aspiration is definitively diagnosed preoperatively in only about half of cases. Clinically suspected foreign-body aspiration should ultimately be ruled out by bronchoscopy. Treatment Foreign-Body Management Conscious Children Unconscious Children The foregoing recommendations are directed primarily at a first responder who has neither access to nor the skills to use airway management equipment. For unconscious children in emergency departments, direct laryngoscopy, visualization, and removal of the foreign body with McGill forceps should be attempted rapidly. Until this equipment is ready, basic life support techniques should be used. Conscious child, Choking but some ventilation/ vocalization

Encourage coughing

Inability to cough vocalize or breathe

Alternating sequence of five back blows and five chest thrusts

Insititute CPRwith patient supine on floor

Heimlich maneuver only indicated in older children

Continue until relief of obstruction or child unconscious

The American Heart Association specifically discourages two common maneuvers used with adult patients:

1. The Heimlich maneuver for patients younger than1 year, because of the potential for injury to abdominal organs, and

2. Blind finger sweeps, because of the possibility of pushing the foreign body farther into the airway. Unconscious child

Inspect airway

Only remove if object visible Avoid blind finger sweeps

First attempt ventilation If obstruction still present

Airway clearance maneuvers as above to be continued

Attempt at ventilation between cycles of back blows and chest thrusts Laryngeal Trauma

External laryngeal trauma is a rare but potentially lethal injury. occurring in approximately 1 in every 137,000 inpatient admissions. Etiology Blunt trauma to the larynx occurs primarily as the result of motor vehicle accidents (dashboard injuries), personal assaults, or sports injuries. The basic mechanism for blunt external injury is compression of the larynx on the anterior cervical bodies. Injuries include: endolaryngeal mucosal tears, cartilaginous fractures, and dislocations of the cricoarytenoid joints. The clothesline injury is a form of blunt laryngeal trauma that typically occurs when the victim is riding a motorcycle or snowmobile and the neck strikes a linear stationary object, such as a wire fence or tree limb. The transfer of such a large amount of force to the neck crushes the thyroid cartilage and may cause laryngotracheal separation. Asphyxiation often occurs at the scene, and survivors of such injuries may have an airway held together precariously by mucous membranes bridging the cartilage. If this injury is suspected, the patient should undergo emergent tracheostomy without attempted intubation. Clinical features The signs and symptoms of laryngeal trauma include: hoarseness, anterior neck pain to palpation, dyspnea, stridor, dysphagia, cough, and/or hemoptysis. Injuries may be asymptomatic initially, except for a subtle change in voice. With more significant or worsening injury, pain, dyspnea, or cough develop, and subcutaneous emphysema may become evident. When the laryngeal lumen is severely compromised, aphonia and apnea may occur, signaling the need for immediate establishment of an alternative airway. Management If the airway is stable, a thorough physical examination of the neck and larynx is required. Bleeding, expanding hematomas, bruits, and loss of pulses are signs associated with vascular injury. Flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy with the patient sitting upright allows immediate assessment of airway integrity and should be done before CT scan of the neck. In patients with adequate airways, CT examination can delineate the extent of injury. Cervical spine radiographs should be performed to evaluate for vertebral injury, a common concurrent injury. The two primary goals in the management of acute laryngeal trauma are preservation of life by maintaining the airway and restoration of function. When the laryngeal lumen cannot be visualized because of gross anatomic disruption or edema and hemorrhage, urgent tracheostomy is the preferred method of controlling the airway and avoiding further injury to the larynx. An emergent tracheotomy is performed through a midline vertical skin incision, and the trachea should be entered at a level lower than usual (fourth or fifth tracheal ring). Cricothyrotomy may be difficult because of cervical emphysema and swelling and should be avoided if possible in suspected laryngeal trauma because it may further injure the subglottis. Angioedema of the Upper Airway Angioedema is a nondemarcated swelling of the dermal or submucosal layers of the skin or mucosa. It is usually nonpruritic but can be painful. Angioedema of the upper airway can have sudden onset and rapid progression. There are four main etiologies: 1) congenital or acquired loss of C1 esterase inhibitor, 2) IgE-mediated type I allergic reaction to food, drug, or environmental exposure, 3) adverse reaction to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy, and 4) idiopathic. A known diagnosis can direct therapy, but many patients with angioedema have no obvious cause at presentation. C1 Esterase deficiency C1 esterase inhibitor is the main regulator of the activation steps of the classical complement pathway, and its genetic deficiency is the cause of hereditary angioedema (HAE). Diagnosis The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with a history of recurrent peripheral angioedema and abdominal pain. Diagnosis is confirmed by measuring blood levels of C1 and C4 esterase inhibitor, although these tests usually cannot be obtained during an acute emergency department visit. Treatment Patients with HAE respond poorly to the usual treatments of angioedema outlined below. Epinephrine can produce some improvement in early acute attacks. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) replaces the missing inhibitor protein and can improve symptoms. However, a few patients may become more edematous after FFP, and it is not recommended in life-threatening laryngeal edema. Patients with life-threatening edema should undergo fiberoptic intubation with preparation for an emergent surgical airway. Attacks can be prevented with long-term use of acetylated artificial androgens or regular infusions of the enzyme. Several medications, including estrogens and ACE inhibitors, increase the severity and frequency of HAE attacks, and patients should be advised to stop these. Other causes Treatment of upper airway angioedema usually is empirical. Intravenous access should be established and the airway examined with fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy as soon as possible. For severe symptoms, epinephrine 1:1000 solution can be given SC in a dose of 0.01 mg/kg, not to exceed 0.3 mg, or the same dose can be administered by inhalation as racemic epinephrine. The dose can be repeated every 15 to 20 min as needed. Classically, diphenhydramine is given IV at 1 to 2 mg/kg, up to a maximum of 50 mg. If the airway is stable, 10 mg of cetirizine can be given PO instead, resulting in less sedation. Methylprednisolone 40 to 125 mg IV should be given, although steroids will not be effective for several hours. If nasopharyngoscopy demonstrates laryngotracheal edema, the patient should be admitted. If there is no airway edema, the patient can be discharged after several hours observation demonstrates clinical improvement. Peritonsillar Abscess Peritonsillar abscess, or quinsy, is the most common deep neck infection. Although most occur in young adults, immune compromised and diabetic patients are at increased risk. Most abscesses develop as a complication of tonsillitis or pharyngitis, but they can also result from odontogenic spread, recent dental procedures, and local mucosal trauma. They recur in 10% to 15% of patients.

The peritonsillar space includes the superior aspect of the tonsil and the area lateral to the adenoids to the area of the pyriform sinus. Once a tonsillar infection has escaped the boundary of the tonsillar capsule, purulent material may flow relatively freely throughout this area. These anatomic relationships are important to remember, as they help to explain the classic physical findings of this disease process. Clinical findings Patients present with a fever, severe sore throat that is often out of proportion to physical findings, localization of symptoms to one side of the throat, trismus, drooling, dysphagia, dysphonia, fetid breath, and ipsilateral ear pain. The uvula and anterior pillar of the tonsil on the affected side may be displaced away from the involved tonsil. The involved tonsil is, as a rule, anteriorly and medially displaced. Cervical adenopathy is often present but does not differentiate this process from the much more common causes of pharyngitis. When uvular deviation, marked soft palate displacement, severe trismus, airway compromise, or localized areas of fluctuance are noted, the diagnosis of peritonsillar abscess can be made with confidence and no imaging study is required. In a child with trismus, oral examination and diagnosis may be impossible and CT scan may be considered if airway obstruction is excluded, or another option is a bedside ultrasound. In less obvious cases with minimal or no trismus, no localized areas of fluctuance, and no displacement of pharyngeal structures, differentiating peritonsillar abscess from peritonsillar cellulitis is difficult. If a child appears toxic, the diagnosis should certainly be considered peritonsillar abscess until proven otherwise. In younger children, imaging may be required to help differentiate these processes. Treatment The pathogens involved are similar to those causing tonsillitis, especially streptococcal species, but many infections are polymicrobial and involve anaerobic bacteria. In nontoxic-appearing adolescents with good follow-up, involved parents, and findings most consistent with peritonsillar cellulitis, a trial of antibiotics may be the best choice for initial treatment. Penicillin, a macrolide, or clindamycin are most commonly used.

Post-tonsillectomy Bleeding Postoperative bleeding is a well-known complication of tonsillectomy that can lead to death from airway obstruction or hemorrhagic shock. The incidence ranges from 1 to 6 percent, with approximately half requiring surgical intervention for control of bleeding. Although bleeding can be seen within 24 h of surgery, most hemorrhage occurs between postoperative days 5 and 10. There is a significantly higher incidence of bleeding in patients between 21 and 30 years of age, and hemorrhage is less common in children under the age of 6. Post-tonsillectomy bleeding can be fatal and requires prompt intervention with control of the airway. An otolaryngologist should be consulted early. The patient should be maintained NPO, monitored with pulse oximetry, and kept upright. Intravenous access should be obtained, and blood should be drawn for a CBC, coagulation studies, and type and crossmatch. Direct pressure can be applied to the bleeding tonsillar bed using a tonsillar pack or a 4 x 4 gauze with a suture through it to prevent loss of the pack into the airway. Pressure exerted on the lateral pharyngeal wall, avoiding midline manipulation, will decrease stimulation of the gag reflex. The packs can be moistened with thrombin or an equivolume solution of 1:1000 epinephrine and 1 percent lidocaine. Massive bleeding is rare, but when it occurs, intubation may be the only means of protecting the airway. This is always difficult, with oropharyngeal edema from recent surgery and blood obscuring visualization of the cords. Plans should be made for an emergent cricothyrotomy prior to attempting intubation. Pressure alone can be adequate for control of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage until the otolaryngologist arrives. Alternatively, if a bleeding site can be visualized, bleeding may be cauterized with silver nitrate after local infiltration with 1 percent lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. Otolaryngologic consultation in the emergency department is always needed because patients may have a second or even third post- tonsillectomy hemorrhage, and surgery or endovascular embolization may be necessary for definitive control.