Experiencing a strip-squeeze

Have you ever been strip-squeezed? A personal question, you may say. But in the world of bridge, it can happen at any time. If you were sitting West last night at the club’s Wednesday duplicate, you might have experienced it or at any rate had a narrow escape.

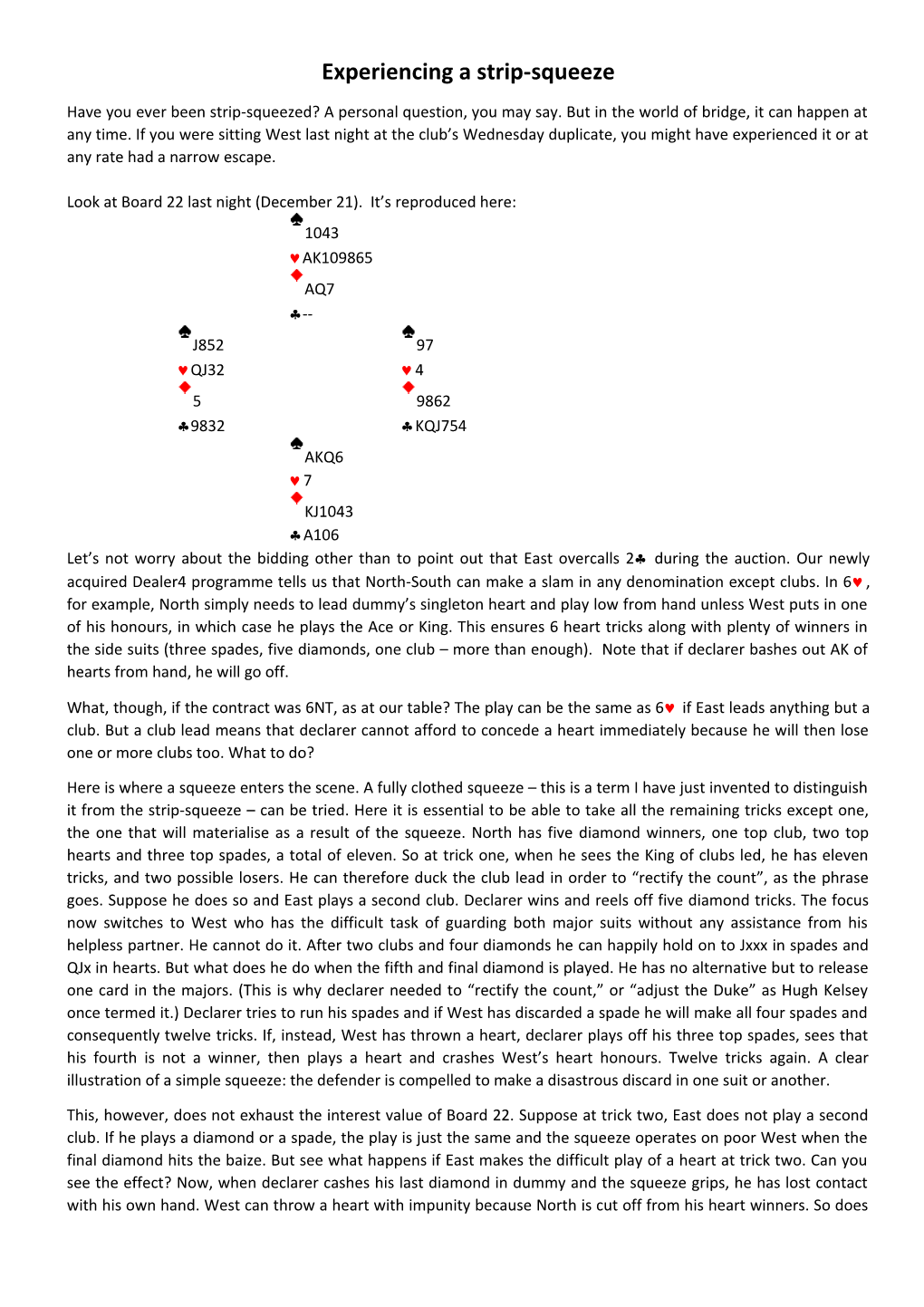

Look at Board 22 last night (December 21). It’s reproduced here: 1043 AK109865 AQ7 .-- J852 97 QJ32 4 5 9862 .9832 .KQJ754 AKQ6 7 KJ1043 .A106 Let’s not worry about the bidding other than to point out that East overcalls 2. during the auction. Our newly acquired Dealer4 programme tells us that North-South can make a slam in any denomination except clubs. In 6, for example, North simply needs to lead dummy’s singleton heart and play low from hand unless West puts in one of his honours, in which case he plays the Ace or King. This ensures 6 heart tricks along with plenty of winners in the side suits (three spades, five diamonds, one club – more than enough). Note that if declarer bashes out AK of hearts from hand, he will go off.

What, though, if the contract was 6NT, as at our table? The play can be the same as 6 if East leads anything but a club. But a club lead means that declarer cannot afford to concede a heart immediately because he will then lose one or more clubs too. What to do?

Here is where a squeeze enters the scene. A fully clothed squeeze – this is a term I have just invented to distinguish it from the strip-squeeze – can be tried. Here it is essential to be able to take all the remaining tricks except one, the one that will materialise as a result of the squeeze. North has five diamond winners, one top club, two top hearts and three top spades, a total of eleven. So at trick one, when he sees the King of clubs led, he has eleven tricks, and two possible losers. He can therefore duck the club lead in order to “rectify the count”, as the phrase goes. Suppose he does so and East plays a second club. Declarer wins and reels off five diamond tricks. The focus now switches to West who has the difficult task of guarding both major suits without any assistance from his helpless partner. He cannot do it. After two clubs and four diamonds he can happily hold on to Jxxx in spades and QJx in hearts. But what does he do when the fifth and final diamond is played. He has no alternative but to release one card in the majors. (This is why declarer needed to “rectify the count,” or “adjust the Duke” as Hugh Kelsey once termed it.) Declarer tries to run his spades and if West has discarded a spade he will make all four spades and consequently twelve tricks. If, instead, West has thrown a heart, declarer plays off his three top spades, sees that his fourth is not a winner, then plays a heart and crashes West’s heart honours. Twelve tricks again. A clear illustration of a simple squeeze: the defender is compelled to make a disastrous discard in one suit or another.

This, however, does not exhaust the interest value of Board 22. Suppose at trick two, East does not play a second club. If he plays a diamond or a spade, the play is just the same and the squeeze operates on poor West when the final diamond hits the baize. But see what happens if East makes the difficult play of a heart at trick two. Can you see the effect? Now, when declarer cashes his last diamond in dummy and the squeeze grips, he has lost contact with his own hand. West can throw a heart with impunity because North is cut off from his heart winners. So does this mean East-West can defeat the squeeze and the contract? This would make the computer analysis of the number of makeable tricks wrong. But the software that does the analysis is never wrong.

What we need is a more complex squeeze. Declarer must win the first trick after all (purely to prevent the killing switch to a heart). Then he plays off 5 diamonds. On the fifth diamond (the sixth trick to be played) West is still holding the fort, guarding the hearts with QJx and the spades with Jxxx. At this point declarer has to do some card reading. East has overcalled in clubs and shown up with four diamonds. West has discarded three clubs and followed to one and had originally one diamond. It looks like he may be 4-4-1-4. If so declarer has executed a squeeze which has stripped West not of his guard in either major but instead of his safe exit card, a club. So now declarer plays a small heart towards the AK10. West must split his honours (or else concede a twelfth trick). Declarer can now exploit the fact that he has the ten of spades by playing the nine or ten of hearts. West wins and has to lead either a heart into declarer’s A10 or a spade, which will be won by the ten. Twelve tricks made for a well-deserved match-point top!

A normal squeeze, as I have noted, occurs when declarer has rectified the count by ensuring he can take all the remaining tricks except one. A strip-squeeze, also known as a “squeeze without the count,” can arise when declarer has more than one loser (usually two) but is able first to squeeze the exit cards out of the victim’s hand so he is stripped of them all, then throw him in so that he is forced to concede a trick.

I was West for this hand so did not have to find the squeeze. Would I have found it at the table as declarer? It would be nice to think so. Nice but delusory.

John Ashworth