The Organization and Evolution of the Responder Satellite in Species Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

559.Full.Pdf

Copyright 0 1992 by the Genetics Society of America The Structure and Evolutionof Subtelomeric Y‘ Repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Edward J.Louis’ and James E. Haber Rosenstiel Center and Department of Biology, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts 02254-91 10 Manuscript received September 25, 199 1 Accepted for publication March 28, 1992 ABSTRACT The subtelomeric Y’ family of repeated DNA sequences in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is of unknown origin and function. Y’s vary in copy number and location among strains. Eight Y‘s, from two strains, were cloned and sequenced over the same 3.2-kb interval in order to assess the within- and between-strain variation as well as address their origin and function. One entireY’ sequence was reconstructed from two clones presented here and apreviously sequenced 833-bp region. It contains two large overlapping open reading frames (ORFs). The putative protein sequences have no strong homologies to any known proteins except for one region that has 27% identity with RNA helicases. RNA homologous to each ORF was detected. Comparison of the sequences revealed that the known long (Y’-L) and short (Y’-S) size classes, which coexist within cells, differ by several insertions and/or deletions within this region. The Y’-Ls from strain Y55 alsodiffer from those of strain YPl by several short deletions in the same region. Most of these deletions appear to have occurred between short (2-10 bp) direct repeats. The single base pair polymorphisms and the deletions are clustered in the first half of the interval compared. There is 0.30-1.13% divergence among Y’-Ls within a strain and 1.15-1.75% divergence between strains in the interval. -

ITS Non-Concerted Evolution and Rampant Hybridization in the Legume Genus Lespedeza

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN ITS non-concerted evolution and rampant hybridization in the legume genus Lespedeza Received: 15 August 2016 Accepted: 30 November 2016 (Fabaceae) Published: 04 January 2017 Bo Xu1, Xiao-Mao Zeng1, Xin-Fen Gao1, Dong-Pil Jin2 & Li-Bing Zhang3 The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) as one part of nuclear ribosomal DNA is one of the most extensively sequenced molecular markers in plant systematics. The ITS repeats generally exhibit high-level within-individual homogeneity, while relatively small-scale polymorphism of ITS copies within individuals has often been reported in literature. Here, we identified large-scale polymorphism of ITS copies within individuals in the legume genus Lespedeza (Fabaceae). Divergent paralogs of ITS sequences, including putative pseudogenes, recombinants, and multiple functional ITS copies were sometimes detected in the same individual. Thirty-seven ITS pseudogenes could be easily detected according to nucleotide changes in conserved 5.8S motives, the significantly lower GC contents in at least one of three regions, and the lost ability of 5.8S rDNA sequence to fold into a conserved secondary structure. The distribution patterns of the putative functional clones were highly different between the traditionally recognized two subgenera, suggesting different rates of concerted evolution in two subgenera which could be attributable to their different extents/frequencies of hybridization, confirmed by our analysis of the single-copy nuclear gene PGK. These findings have significant implications in using ITS marker for reconstructing phylogeny and studying hybridization. Concerted evolution is a form of multigene family evolution in which all the tendency of the different genes in a gene family or cluster are assumed to evolve as a unit in concert1,2. -

Gene Conversion in Duplicated Genes

Genes 2011, 2, 394-396; doi:10.3390/genes2020394 OPEN ACCESS genes ISSN 2073-4425 www.mdpi.com/journal/genes Editorial Special Issue: Gene Conversion in Duplicated Genes Hideki Innan Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Hayama, Kanagawa 240-0193, Japan; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 13 June 2011 / Accepted: 17 June 2011 / Published: 17 June 2011 Gene conversion is an outcome of recombination, causing non-reciprocal transfer of a DNA fragment. Several decades later than the discovery of crossing over, gene conversion was first recognized in fungi when non-Mendelian allelic distortion was observed. Gene conversion occurs when a double-strand break is repaired by using homologous sequences in the genome. In meiosis, there is a strong preference to use the orthologous region (allelic gene conversion), which causes non-Mendelian allelic distortion, but paralogous or duplicated regions can also be used for the repair (inter-locus gene conversion, also referred to as non-allelic and ectopic gene conversion). The focus of this special issue is the latter, interlocus gene conversion; the rate is lower than allelic gene conversion but it has more impact on phenotype because more drastic changes in DNA sequence are involved. This special issue consists of 10 review papers covering various aspects of interlocus gene conversion. Hastings [1] provides a review on the basic mechanisms of gene conversion in meiotic cells. Gene conversion occurs through the repair process of a double-strand break with the formation of a D-loop. Gene conversion also occurs in mitosis; the mechanisms should be the same but different proteins may be involved. -

Concerted Evolution of Rdna in Recently Formed Tragopogon Allotetraploids Is Typically Associated with an Inverse Correlation Between Gene Copy Number and Expression

Copyright Ó 2007 by the Genetics Society of America DOI: 10.1534/genetics.107.072751 Concerted Evolution of rDNA in Recently Formed Tragopogon Allotetraploids Is Typically Associated With an Inverse Correlation Between Gene Copy Number and Expression Roman Matya´sˇek,* Jennifer A. Tate,† Yoong K. Lim,‡ Hana Sˇrubarˇova´,* Jin Koh,† Andrew R. Leitch,‡ Douglas E. Soltis,† Pamela S. Soltis§ and Alesˇ Kovarˇ´ık*,1 *Institute of Biophysics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, v.v.i, Laboratory of Molecular Epigenetics, Kra´lovopolska´ 135, CZ-61265 Brno, Czech Republic, †Department of Botany, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, ‡School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, E1 4NS, UK and §Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 Manuscript received March 1, 2007 Accepted for publication May 23, 2007 ABSTRACT We analyzed nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA) transcription and chromatin condensation in individuals from several populations of Tragopogon mirus and T. miscellus, allotetraploids that have formed repeatedly within only the last 80 years from T. dubius and T. porrifolius and T. dubius and T. pratensis, respectively. We identified populations with no (2), partial (2), and complete (4) nucleolar dominance. It is probable that epigenetic regulation following allopolyploidization varies between populations, with a tendency toward nucleolar dominance by one parental homeologue. Dominant rDNA loci are largely decondensed at interphase while silent loci formed condensed heterochromatic regions excluded from nucleoli. Those populations where nucleolar dominance is fixed are epigenetically more stable than those with partial or incomplete dominance. Previous studies indicated that concerted evolution has partially homogenized thousands of parental rDNA units typically reducing the copy numbers of those derived from the T. -

Intragenomic Variation and Evolution of the Internal Transcribed Spacer of the Rrna Operon in Bacteria

J Mol Evol (2007) 65:44À67 DOI: 10.1007/s00239-006-0235-3 Intragenomic Variation and Evolution of the Internal Transcribed Spacer of the rRNA Operon in Bacteria Frank J. Stewart, Colleen M. Cavanaugh Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, The Biological Laboratories, 16 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Received: 20 October 2006 / Accepted: 13 March 2007 [Reviewing Editor: Dr. Margaret Riley] Abstract. Variation in the internal transcribed Key words: Bacterial diversity — Intergenic spacer spacer (ITS) of the rRNA (rrn) operon is increasingly — Concerted evolution — Gene conversion — used to infer population-level diversity in bacterial Ribosomal RNA (rrn) operon — Copy number — communities. However, intragenomic ITS variation Multigene family may skew diversity estimates that do not correct for multiple rrn operons within a genome. This study characterizes variation in ITS length, tRNA compo- sition, and intragenomic nucleotide divergence across Introduction 155 Bacteria genomes. On average, these genomes en- code 4.8 rrn operons (range: 2À15) and contain 2.4 The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region sepa- unique ITS length variants (range: 1À12) and 2.8 rating the bacterial 16S and 23S rRNA genes unique sequence variants (range: 1À12). ITS variation is increasingly used to assess microheterogeneity in stems primarily from differences in tRNA gene com- the growing field of bacterial population genetics position, with ITS regions containing tRNA-Ala + (e.g., Di Meo et al. 2000; Boyer et al. 2002; Hurtado tRNA-Ile (48% of sequences), tRNA-Ala or tRNA-Ile et al. 2003; Vogel et al. 2003; Brown and Fuhrman (10%), tRNA-Glu (11%), other tRNAs (3%), or no 2005; DeChaine et al. -

The Birth- And- Death Evolution of Multigene Families Revisited J.M

Garrido- Ramos MA (ed): Repetitive DNA. Genome Dyn. Basel, Karger, 2012, vol 7, pp 170–196 The Birth- and- Death Evolution of Multigene Families Revisited J.M. Eirín- Lópeza и L. Rebordinosb и A.P. Rooneyd и J. Rozasc aCHROMEVOL- XENOMAR Group, Departamento de Biología Celular y Molecular, Universidade da Coruña, A Coruña, bÁrea de Genética, Facultad de Ciencias del Mar y Ambientales, Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz, cDepartament de Genètica y Institut de Recerca de la Biodiversitat (IRBio), Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; dCrop Bioprotection Research Unit, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture, Peoria, Ill., USA Abstract For quite some time, scientists have wondered how multigene families come into existence. Over the last several decades, a number of genomic and evolutionary mechanisms have been discov- ered that shape the evolution, structure and organization of multigene families. While gene dupli- cation represents the core process, other phenomena such as pseudogene formation, gene loss, recombination and natural selection have been found to act in varying degrees to shape the evolu- tion of gene families. How these forces influence the fate of gene duplicates has ultimately led molecular evolutionary biologists to ask the question: How and why do some duplicates gain new functions, whereas others deteriorate into pseudogenes or even get deleted from the genome? What ultimately lies at the heart of this question is the desire to understand how multigene families originate and diversify. The birth- and-death model of multigene family evolution provides a frame- work to answer this question. However, the growing availability of molecular data has revealed a much more complex scenario in which the birth- and- death process interacts with different mecha- nisms, leading to evolutionary novelty that can be exploited by a species as means for adaptation to various selective challenges. -

1837.Full.Pdf

Copyright Ó 2005 by the Genetics Society of America DOI: 10.1534/genetics.105.047670 Monitoring the Mode and Tempo of Concerted Evolution in the Drosophila melanogaster rDNA Locus Karin Tetzlaff Averbeck and Thomas H. Eickbush1 Department of Biology, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York 14627-0211 Manuscript received July 1, 2005 Accepted for publication August 25, 2005 ABSTRACT Non-LTR retrotransposons R1 and R2 have persisted in rRNA gene loci (rDNA) since the origin of arthropods despite their continued elimination by the recombinational mechanisms of concerted evolution. This study evaluated the short-term evolutionary dynamics of the rDNA locus by measuring the divergence among replicate Drosophila melanogaster lines after 400 generations. The total number of rDNA units on the X chromosome of each line varied from 140 to 310, while the fraction of units inserted with R1 and R2 retrotransposons ranged from 37 to 65%. This level of variation is comparable to that found in natural population surveys. Variation in locus size and retrotransposon load was correlated with large changes in the number of uninserted and R1-inserted units, yet the numbers of R2-inserted units were relatively unchanged. Intergenic spacer (IGS) region length variants were also used to evaluate changes in the rDNA loci. All IGS length variants present in the lines showed significant increases and decreases of copy number. These studies, combined with previous data following specific R1 and R2 insertions in these lines, help to define the type and distribution, both within the locus and within the individual units, of recombinational events that give rise to the concerted evolution of the rDNA locus. -

Concepts of Punctuated Equilibrium, Concerted Evolution and Coevolution

Journal of Scientific Research Vol. 58, 2014 : 15-26 Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi ISSN : 0447-9483 EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY : CONCEPTS OF PUNCTUATED EQUILIBRIUM, CONCERTED EVOLUTION AND COEVOLUTION Bashisth N. Singh Genetics Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005 [email protected] Abstract For more than a century, evolution has become a corner stone of biology. In the middle of the last century, Ernst Mayr established Evolutionary Biology as a separate field of studies in USA. In 1744, Haller, a Swiss biologist coined the term ’Evolutio’ (a Latin word for Evolution) which means to unroll or unfold. It was used to describe the progressive unfolding of structures during development. In the middle of nineteenth century, Herbert Spencer, an English Philosopher popularized the word Evolution. He has also been called as Father of Social Darwinism. His idea about evolution was influenced by both Lamarckism and Darwinism. From time to time, various theories have been proposed to explain the mechanisms of evolution. These theories are: Lamarckism, Darwinism, theory of germplasm, isolation theory, mutation theory, synthetic theory and neutral theory. These theories except synthetic theory explain the mechanisms of evolution by giving more emphasis on single factor. However, the modern synthetic theory which was developed by the contributions of many evolutionary biologists, combines many factors in one theory and is widely accepted theory of evolution. There exists controversy between neutralists vs. selectionists. Further, Lamarckism (theory of inheritance of acquired characters) has been rejected and is of only historical significance. In the last century, a few new concepts of evolutionary biology were proposed by evolutionary biologists. -

Transposable Elements and Genome Size Dynamics in Gossypium Jennifer S

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 Transposable elements and genome size dynamics in Gossypium Jennifer S. Hawkins Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons Recommended Citation Hawkins, Jennifer S., "Transposable elements and genome size dynamics in Gossypium" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15894. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15894 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transposable elements and genome size dynamics in Gossypium by Jennifer S. Hawkins A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Botany Program of Study Committee: Jonathan F. Wendel, Major Professor Lynn G. Clark John D. Nason Thomas Peterson Randy Shoemaker Dan Voytas Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Jennifer S. Hawkins, 2007. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3274835 UMI Microform 3274835 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ABSTRACT vi CHAPTER ONE. -

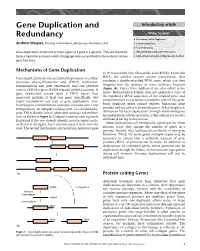

"Gene Duplication and Redundancy". In: Encyclopedia of Life Science

Gene Duplication and Introductory article Redundancy Article Contents . Mechanisms of Gene Duplication Andreas Wagner, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA . Protein-coding Genes . Gene Redundancy Gene duplications create one or more copies of a gene in a genome. They are important . RNA-coding Genes and Concerted Evolution forces of genome evolution which change genome size and lead to the evolution of new . Limits of Genome Analysis to Study Genome Evolution gene functions. Mechanisms of Gene Duplication to be transcribed into ribonucleic acid (RNA). From this Gene duplications are the accidental byproducts of cellular RNA, the cellular enzyme reverse transcriptase then processes (deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) replication, produces a double-stranded DNA copy, which can then recombination and gene expression) that can generate integrate into the genome at some arbitrary location copies of DNA regions (DNA repeats) within a genome. A (Figure 1b). Genes thus duplicated are also called retro- gene duplication occurs when a DNA repeat thus genes. Retroposition usually does not generate a copy of generated includes at least one gene. Specifically, two the regulatory DNA sequences of the original gene, and major mechanisms can lead to gene duplication: non- sometimes does not generate a complete copy of the gene. homologous recombination (unequal crossing-over) and Such duplicate genes cannot express functional gene retroposition. In unequal crossing-over, two nonhomolo- product and are called retropseudogenes. A key diagnostic gous DNA double helices align and undergo recombina- distinction between duplication through nonhomologous tion, as shown in Figure 1a. Unequal crossing-over is greatly recombination and retroposition is that introns are usually facilitated if the two strands already contain repeat units, eliminated during retroposition. -

Highly Efficient Concerted Evolution in the Ribosomal DNA Repeats: Total Rdna Repeat Variation Revealed by Whole-Genome Shotgun Sequence Data

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 2, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Letter Highly efficient concerted evolution in the ribosomal DNA repeats: Total rDNA repeat variation revealed by whole-genome shotgun sequence data Austen R.D. Ganley1,3,4,5 and Takehiko Kobayashi1,2,4 1National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki, 444-8585 Japan; 2SOKENDAI, Okazaki, 444-8585 Japan; 3Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA Repeat families within genomes are often maintained with similar sequences. Traditionally, this has been explained by concerted evolution, where repeats in an array evolve “in concert” with the same sequence via continual turnover of repeats by recombination. Another form of evolution, birth-and-death evolution, can also explain this pattern, although in this case selection is the critical force maintaining the repeats. The level of intragenomic variation is the key difference between these two forms of evolution. The prohibitive size and repetitive nature of large repeat arrays have made determination of the absolute level of intragenomic repeat variability difficult, thus there is little evidence to support concerted evolution over birth-and-death evolution for many large repeat arrays. Here we use whole-genome shotgun sequence data from the genome projects of five fungal species to reveal absolute levels of sequence variation within the ribosomal RNA gene repeats (rDNA). The level of sequence variation is remarkably low. Furthermore, the polymorphisms that are detected are not functionally constrained and seem to exist beneath the level of selection. These results suggest the rDNA is evolving via concerted evolution. Comparisons with a repeat array undergoing birth-and-death evolution provide a clear contrast in the level of repeat array variation between these two forms of evolution, confirming that the rDNA indeed does evolve via concerted evolution. -

Polymorphism and Concerted Evolution in a Tandemly Repeated Gene Family: 5S Ribosomal DNA in Diploid and Allopolyploid Cottons

J Mol Evol (1996) 42:685-705 JOURNAL OF OLECULAR EVOLUTION ©Springer-Verlag New York Inc. 1996 Polymorphism and Concerted Evolution in a Tandemly Repeated Gene Family: 5S Ribosomal DNA in Diploid and Allopolyploid Cottons Richard C. Cronn/ Xinping Zhao/ Andrew H. Paterson,3 Jonathan F. Wendel1 1 Department of Botany, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA 2University of Michigan Medical Center, MSRB II, C568, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0672, USA 3Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX 77843-2474, USA Received: 27 June 1995 I Accepted: 6 November 1995 Abstract. 5S RNA genes and their nontranscribed forces allow equivalent levels of sequence polymor spacers are tandemly repeated in plant genomes at one or phism to accumulate in the 5S gene and spacer se more chromosomal loci. To facilitate an understanding quences, but fixation of mutations is nearly prohibited in of the forces that govern 5S rDNA evolution, copy the 5S gene. As a consequence, fixed interspecific dif number estimation and DNA sequencing were conducted ferences are statistically underrepresented for 5S genes. for a phylogenetically well-characterized set of 16 dip This result explains the apparent paradox that despite loid species of cotton (Gossypium) and 4 species repre similar levels of gene and spacer diversity, phylogenetic senting allopolyploid derivatives of the diploids. Copy analysis of spacer sequences yields highly resolved trees, number varies over twentyfold in the genus, from ap whereas analyses based on 5S gene sequences do not. proximately 1,000 to 20,000 copies/2C genome. When superimposed on the organismal phylogeny, these data Key words: 5S rDNA - Concerted evolution- Gos reveal examples of both array expansion and contraction.