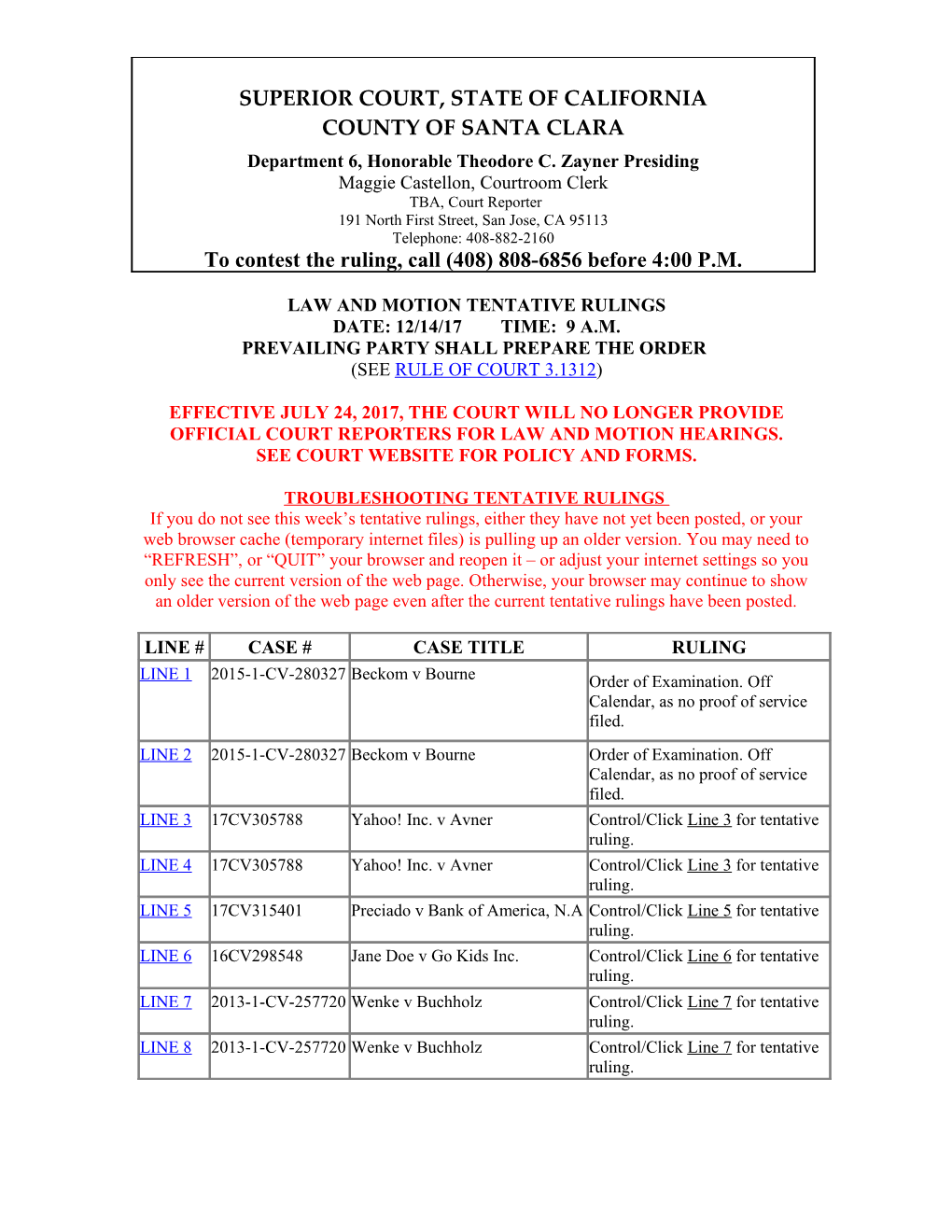

SUPERIOR COURT, STATE OF CALIFORNIA COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA Department 6, Honorable Theodore C. Zayner Presiding Maggie Castellon, Courtroom Clerk TBA, Court Reporter 191 North First Street, San Jose, CA 95113 Telephone: 408-882-2160 To contest the ruling, call (408) 808-6856 before 4:00 P.M.

LAW AND MOTION TENTATIVE RULINGS DATE: 12/14/17 TIME: 9 A.M. PREVAILING PARTY SHALL PREPARE THE ORDER (SEE RULE OF COURT 3.1312)

EFFECTIVE JULY 24, 2017, THE COURT WILL NO LONGER PROVIDE OFFICIAL COURT REPORTERS FOR LAW AND MOTION HEARINGS. SEE COURT WEBSITE FOR POLICY AND FORMS.

TROUBLESHOOTING TENTATIVE RULINGS If you do not see this week’s tentative rulings, either they have not yet been posted, or your web browser cache (temporary internet files) is pulling up an older version. You may need to “REFRESH”, or “QUIT” your browser and reopen it – or adjust your internet settings so you only see the current version of the web page. Otherwise, your browser may continue to show an older version of the web page even after the current tentative rulings have been posted.

LINE # CASE # CASE TITLE RULING LINE 1 2015-1-CV-280327 Beckom v Bourne Order of Examination. Off Calendar, as no proof of service filed. LINE 2 2015-1-CV-280327 Beckom v Bourne Order of Examination. Off Calendar, as no proof of service filed. LINE 3 17CV305788 Yahoo! Inc. v Avner Control/Click Line 3 for tentative ruling. LINE 4 17CV305788 Yahoo! Inc. v Avner Control/Click Line 3 for tentative ruling. LINE 5 17CV315401 Preciado v Bank of America, N.A Control/Click Line 5 for tentative ruling. LINE 6 16CV298548 Jane Doe v Go Kids Inc. Control/Click Line 6 for tentative ruling. LINE 7 2013-1-CV-257720 Wenke v Buchholz Control/Click Line 7 for tentative ruling. LINE 8 2013-1-CV-257720 Wenke v Buchholz Control/Click Line 7 for tentative ruling. SUPERIOR COURT, STATE OF CALIFORNIA COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA Department 6, Honorable Theodore C. Zayner Presiding Maggie Castellon, Courtroom Clerk TBA, Court Reporter 191 North First Street, San Jose, CA 95113 Telephone: 408-882-2160 To contest the ruling, call (408) 808-6856 before 4:00 P.M.

LAW AND MOTION TENTATIVE RULINGS LINE # CASE # CASE TITLE RULING LINE 9 16CV301867 Sinco Technologies v Soon Motion to compel deposition is off calendar as moot. Motion was advanced to 11/30/17 and decided by the court, and counsel have entered into stipulation re deposition filed 12/11/17. LINE 10 16CV301867 Sinco Technologies v Soon Motion for protective order is DENIED, except for Document Demand #58, for which it is GRANTED. LINE 11 17CV314431 Lee v K& L Supply Company, Defendant’s motion to dismiss is Inc DENIED at this time, on the authority and grounds stated in the motion, without prejudice. LINE 12 2013-1-CV-254940 Lobel Financial Corp v Torres Defendant’s Claim of Exemption is DENIED. Withholding shall be allowed at $85 per pay period. LINE 13 LINE 14 LINE 15 LINE 16 LINE 17 LINE 18 LINE 19 LINE 20 LINE 21 LINE 22 LINE 23 LINE 24 LINE 25 LINE 26 LINE 27 LINE 28 LINE 29 SUPERIOR COURT, STATE OF CALIFORNIA COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA Department 6, Honorable Theodore C. Zayner Presiding Maggie Castellon, Courtroom Clerk TBA, Court Reporter 191 North First Street, San Jose, CA 95113 Telephone: 408-882-2160 To contest the ruling, call (408) 808-6856 before 4:00 P.M.

LAW AND MOTION TENTATIVE RULINGS LINE # CASE # CASE TITLE RULING LINE 30 Calendar line 1

- oo0oo -

Calendar line 2

- oo0oo - Calendar lines 3 and 4

Case Name: Yahoo! Inc. v. Ross Avner, et al. Case No.: 17-CV-305788

Currently before the Court are the following matters: (1) the special motion by defendant and cross-complainant LAS Technologies PTE LTD (“LAS Tech”) to strike the fifth through twelfth causes of action of the second amended complaint (“SAC”) of plaintiff and cross-defendant Yahoo! Inc. (“Yahoo”); and (2) the demurrer by LAS Tech to the fifth through twelfth causes of action of Yahoo’s SAC.

Factual and Procedural Background

This action arises out of Avner’s alleged disclosure of Yahoo’s confidential and proprietary information to LAS Tech. (SAC, ¶¶ 1-10.) Avner was a former Senior Director of Yahoo responsible for leading the business of Yahoo’s Games property. (Id. at ¶ 1.) In his position at Yahoo, Avner had access to highly confidential and proprietary Yahoo information, particularly with respect to Yahoo Games. (Id. at ¶ 3.) Avner worked closely with LAS Tech on behalf of Yahoo from 2007, until he left his employment with Yahoo in late 2012. (Id. at ¶ 2.) LAS Tech is a game-developer that licensed gaming content to Yahoo in exchange for a share of certain advertising revenue. (Id. at ¶¶ 2 and 38.) During his employment, Avner was given access to confidential Yahoo information that related to Yahoo’s business dealings with LAS Tech. (Id. at ¶ 39.)

Under the terms of confidentiality and separation agreements between Yahoo and Avner, Avner was bound not to disclose any confidential or proprietary information to third parties. (SAC, ¶¶ 1 and 3.) In addition, Avner agreed to cooperate with Yahoo in response to any investigations, claims, or potential litigation that related to his work with Yahoo and provide Yahoo with copies of all correspondence in connection with any legal proceedings involving or relating to Yahoo. (Id. at ¶ 3.) Avner further agreed that he would not work with or cooperate with any third party to develop any actual or threatened claim or cause of action against Yahoo. (Ibid.)

After leaving Yahoo, Avner started his own company, Point Publishing, which “offered consulting and promotion services to gaming companies, including LAS Tech, to assist with marketing the content to licensees, including Yahoo.” (SAC, ¶ 2.) “Avner[, through Point Publishing,] provided content acquisition and game promotions services to LAS Tech from 2013 through at least 2015.” (Id. at ¶ 42.) Point Publishing had a separate agreement with Yahoo, which contained a confidentiality provision prohibiting it from sharing Yahoo’s confidential or proprietary information with third parties, such as LAS Tech. (Id. at ¶ 4.) In addition, Point Publishing agreed to “pay Yahoo a percentage of in-game purchases with respect to games that [it] brought to Yahoo in exchange for Yahoo placing the games on Yahoo properties.” (Id. at ¶ 43.)

Avner allegedly breached his contractual and fiduciary obligations to Yahoo, and violated the confidentiality and severance agreements, by working as a “litigation consultant” for LAS Tech. (SAC, ¶ 1.) “In an apparent attempt to leverage Avner’s special knowledge of highly confidential and proprietary Yahoo information, LAS Tech has sought to pressure Yahoo into settling trumped up claims being asserted by LAS Tech against Yahoo.” (Ibid.) “In coordination with Avner/Point Publishing, LAS Tech sent Yahoo a demand letter on June 15, 2016, asserting that [it] was owed millions of dollars under its licensing agreement with Yahoo for alleged accounting errors dating back to 2007.” (Id. at ¶¶ 5 and 45-46.) “In violation of its duties of good faith and fair dealing, and an apparent attempt to intimidate Yahoo and give[its] claims an air of legitimacy, LAS Tech told Yahoo that it had a ‘source,’ and it peppered portions of its demand letter with references to information that did not appear to be public.” (Id. at ¶ 5.)

In response to the demand letter, Yahoo conducted a preliminary investigation and identified one accounting error, for which it transmitted payment to LAS Tech on January 30, 2017. (SAC, ¶ 47.)

In August 2016, Yahoo received an email from LAS Tech’s counsel about the dispute, which copied Avner. (SAC, ¶ 6.) One month later, Yahoo reached out to Avner to discuss the demand letter, Avner never responded to Yahoo at LAS Tech’s instruction. (Id. at ¶¶ 6 and 48.) Subsequently, LAS Tech admitted that “it had been working with Avner to develop its case against Yahoo” and “Avner had been retained by LAS Tech to help with the litigation against Yahoo in 2016, referring to Avner as an important ‘consulting expert’ for the litigation team working up claims against Yahoo.” (Id. at ¶¶ 7, 49-50, and 52.) LAS Tech also claimed that Avner had worked on its behalf since 2013, and “any direct communication with [Avner is] proscribed by the California Rules of Professional Conduct.” (Id. at ¶¶ 8 and 54.) LAS also stated that it “had directed Avner not to respond to Yahoo’s attempt to contact him in September 2016.” (Id. at ¶ 54.) “LAS Tech’s … attempts to cloak its communications with Avner in the attorney-client and work product privileges have limited Yahoo’s ability to know exactly what confidential Yahoo information was shared between Avner and LAS Tech.” (Id. at ¶ 9.)

Yahoo alleges that “LAS Tech has leveraged [its relationship with Avner] to peddle half-truths and misstatements about Yahoo in mounting an unwarranted attack against Yahoo that has already cost Yahoo substantial amounts of money and business disruption to investigate and defend.” (SAC, ¶ 58.)

Based on the foregoing, Yahoo filed the operative SAC against Avner, Point Publishing, and LAS Tech, alleging causes of action for: (1) breach of confidentiality agreement (against Avner); (2) breach of separation agreement (against Avner); (3) breach of Point Publishing agreement (against Point Publishing); (4) interference with contract (against Avner); (5) intentional interference with contractual relations (against LAS Tech); (6) intentional interference with contractual relations (against LAS Tech); (7) intentional interference with contractual relations (against LAS Tech); (8) inducing breach of confidentiality agreement (against LAS Tech); (9) inducing breach of separation agreement (against LAS Tech); (10) inducing breach of Point Publishing agreement (against LAS Tech) ; (11) injunctive relief (against all defendants); and (12) declaratory relief (against all defendants). On August 9, 2017, LAS Tech filed the instant demurrer and special motion to strike. Yahoo filed papers in opposition to both matters on October 31, 2017. On November 6, 2017, LAS Tech filed reply papers. Most recently, on December 4, 2017, Yahoo filed a notice of lodging and request to file sur-replies in support of its opposition to both matters.

Discussion I. LAS Tech’s Special Motion to Strike

LAS Tech brings this special motion to strike the fifth through twelfth causes of action of the SAC under Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16 on the grounds that Yahoo’s claims arise from protected activity and Yahoo cannot demonstrate a probability of prevailing on its claims.

A. Legal Standard

“Section 425.16 provides … that ‘A cause of action against a person arising from any act of that person in furtherance of the person’s right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue shall be subject to a special motion to strike, unless the court determines that the plaintiff has established that there is a probability that the plaintiff will prevail on the claim.’ [Citation.] ‘As used in this section, “act in furtherance of a person’s right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue” includes:’ ” (1) any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law; (2) any written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law; (3) any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest; or (4) any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest. (Navellier v. Sletten (2002) 29 Cal.4th 82, 87–88 (Navellier); Code Civ. Proc., § 425.16. subd. (e).)

The statute “posits … a two-step process for determining whether an action is a SLAPP. First, the court decides whether the defendant has made a threshold showing that the challenged cause of action is one arising from protected activity. [Citation.] ‘A defendant meets this burden by demonstrating that the act underlying the plaintiff's cause fits one of the categories spelled out in section 425.16, subdivision (e)’ [citation]. If the court finds that such a showing has been made, it must then determine whether the plaintiff has demonstrated a probability of prevailing on the claim. [Citations.]” (Navellier, supra, 29 Cal.4th at p. 88.) “ ‘ “To satisfy this prong, the plaintiff must ‘state [ ] and substantiate [ ] a legally sufficient claim.’ [Citation.] ‘Put another way, the plaintiff “must demonstrate that the complaint is both legally sufficient and supported by a sufficient prima facie showing of facts to sustain a favorable judgment if the evidence submitted by the plaintiff is credited.” ’ ” ’ [Citation.]” (Freeman v. Schack (2007) 154 Cal.App.4th 719, 726–27.) “The second prong … is considered under a standard similar to that employed in determining nonsuit, directed verdict or summary judgment motions. … The plaintiff may not rely solely on its complaint, even if verified; instead, its proof must be made upon competent admissible evidence. [Citation.] In reviewing the plaintiff’s evidence, the court does not weigh it; rather, it simply determines whether the plaintiff has made a prima facie showing of facts necessary to establish its claim at trial. [Citation.]” (Paiva v. Nichols (2008) 168 Cal.App.4th 1007, 1017.)

B. Protected Activity LAS Tech generally argues that Yahoo’s claims against it—the fifth through twelfth causes of action—“must fail because they are a broad-based attack on [its] constitutionally- protected right of petition.” (Mem. Ps. & As., p. 1:14-15.) LAS Tech contends that:

Litigation-related activities, including pre-lawsuit preparations, are in furtherance of a litigant’s right of petition. Claims based on these activities are subject to a special motion to strike under California’s anti-SLAPP statute. [¶] Each and every cause of action the SAC purports to state against [it] arises directly from [its] investigation and preparation of claims against Yahoo in anticipation of litigation. This alone satisfies [its] threshold burden on its anti- SLAPP motion ….

(Id. at pp. 1:16-22 and 3:10-14.) LAS Tech then cites to several allegations in the SAC as well as the case of Dove Audio, Inc. v. Rosenfeld, Meyer & Susman (1996) 47 Cal.App.4th 777 (Dove) to support its contentions. (Id. at pp. 3:14-4:18.) LAS Tech highlights the fact that the plaintiff in Dove, a music publisher, filed a claim for defamation, which arose out of letters the publisher received from an attorney threatening to file a complaint with the state attorney general’s office. (Mem. Ps. & As., p. 4:7-12.) LAS Tech quotes the Court of Appeal’s holding that the attorney communications raised a question of public interest and constituted protected activity as the communications were made in connection with an official proceeding authorized by law. (Dove, supra, 47 Cal.App.4th at p. 784.) LAS Tech concludes that the facts of Dove “are remarkably similar” to the present case because “[t]he SAC alleges that [it] took steps to investigate, including hiring counsel, hiring experts, sending a demand letter, and entering into settlement discussions with Yahoo” and “[t]hese tasks were all undertaken in anticipation of litigation and are therefore protected.” (Mem. Ps. & As., p. 4:19-23.)

The Court finds that LAS Tech’s arguments are not well-taken. As an initial matter, LAS Tech makes no attempt to identify which subpart of Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, subdivision (e) it believes applies in this case.

Moreover, because Dove is distinguishable from the instant case, LAS Tech fails to establish that the subparts applied by the Court of Appeal in Dove are applicable here. In Dove, the Court of Appeal found that the attorney letters at issue constituted protected activity because they were communications made in connection with an official proceeding authorized by law. (Dove, supra, 47 Cal.App.4th at p. 784.) In other words, the letters constituted written statements or writings “made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law” under Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, subdivision (e)(2). (Code Civ. Proc., § 425.16, subd. (e)(2).) Here, it is readily apparent that the fifth through twelfth causes of action primarily arise out of LAS Tech’s conduct—its receipt of confidential information from Avner and its retention (i.e., hiring) of Avner as an expert. (See SAC, ¶¶ 113, 119, 126, 132-32, 138- 39, 145-46, 150, 158.) As the gravamen of claims is the conduct identified above, as opposed to communications, the allegedly wrongful and injury-producing conduct does not fall under Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, subdivision (e)(2). (See Olive Properties v. Coolwaters Enterprises, Inc. (2015) 241 Cal.App.4th 1169, 1175 [The “principal thrust or gravamen” of [plaintiff’s] claim determines whether section 425.16 applies. [Citations.]”].)

The Court of Appeal in Dove also indicated that another basis for its holding was that the attorney communications raised an issue of public interest, which potentially implicates Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, subdivision (e)(3) and (4). (Dove, supra, 47 Cal.App.4th at p. 784; see Code Civ. Proc., § 425.16, subd. (e)(3) and (4) [an “act in furtherance of a person's right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue” includes: … (3) any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest, or (4) any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest”], italics added.) Here, LAS Tech does not attempt to argue that the gravamen of the claims involves a public issue or an issue of public interest. Consequently, LAS Tech do not establish that Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, subdivision (e)(3) or (4) apply.

In light of the foregoing, LAS fails to meet its initial burden to show that the claims arise out of protected activity.

C. Probability of Prevailing

As LAS Tech fails to satisfy the first prong and demonstrate that Yahoo’s claims arise from protected activity, the Court need not address the second prong, i.e., whether Yahoo can demonstrate a probability of prevailing on its claims. In addition, the Court need not address LAS Tech’s objections to evidence Yahoo submitted in support of its opposition. Finally, the Court also declines to consider Yahoo’s request to file sur-reply in support of its opposition to the instant motion as the arguments raised in the sur-reply only address the second prong.

D. Conclusion

Because LAS Tech does not meet its initial burden to show that Yahoo’s claims arise out of protected activity, the special motion to strike the fifth through twelfth causes of action is DENIED.

II. LAS Tech’s Demurrer

LAS Tech demurs to the fifth through twelfth causes of action of the SAC on the ground of failure to allege facts sufficient to constitute a cause of action. (See Code Civ. Proc., § 430.10, subd. (e).) LAS Tech contends that these causes of action fail to state a claim because they are preempted by the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act (“CUTSA”) and barred by the litigation privilege under Civil Code section 47. LAS Tech also contends that “Yahoo’s Separation Agreement claims … fail because the Opposition fails to provide any evidence that [it] knew of the existence of the Separation Agreement or that the hiring of Avner and instruction that he not cooperate with Yahoo would result in a breach of the Agreement.”1 (Reply, p. 4:1-4.)

A. Legal Standard

The function of a demurrer is to test the legal sufficiency of a pleading. (Trs. Of Capital Wholesale Elec. Etc. Fund v. Shearson Lehman Bros. (1990) 221 Cal.App.3d 617, 621.) Consequently, “[a] demurrer reaches only to the contents of the pleading and such matters as may be considered under the doctrine of judicial notice.” (South Shore Land Co. v. Petersen (1964) 226 Cal.App.2d 725, 732, internal citations and quotations omitted; see also Code Civ. Proc., § 430.30, subd. (a).) “It is not the ordinary function of a demurrer to test the truth of the [ ] allegations [in the challenged pleading] or the accuracy with which [the plaintiff] describes the defendant’s conduct. [ ] Thus, [ ] the facts alleged in the pleading are deemed to be true, however improbable they may be.” (Align Technology, Inc. v. Tran (2009) 179 Cal.App.4th 949, 958, internal citations and quotations omitted.) However, while “[a] demurrer admits all facts properly pleaded, [it does] not [admit] contentions, deductions or conclusions of law or fact.” (George v. Automobile Club of Southern California (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1112, 1120.)

B. CUTSA

LAS Tech contends that each cause of action “sounds in misappropriation of trade secrets” and is, therefore, preempted by CUTSA. (Mem. Ps. & As., p. 1:14-17.) LAS Tech points out that the SAC contains the following allegations: Avner disclosed, and it received and used, Yahoo’s confidential information; the confidential information has inherent value that is directly tied to the information’s secrecy; and Yahoo has taken reasonable efforts under the circumstances to protect the confidential information from unauthorized use or disclosure. (Id. at pp. 2:24-3:7.) Based on these allegations, LAS Tech concludes that the SAC is based on the existence of a purported trade secret, i.e., Yahoo’s confidential information, because Civil Code section 3426.1, subdivision (d) defines a trade secret as information that derives independent economic value from not being generally known to the public and is the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy. (Ibid.) LAS Tech contends that the fifth through twelfth causes of action arise out of the same nucleus of facts that would give rise to a claim for misappropriation of trade secrets because the claims all arise out of allegations that Avner obtained and disclosed Yahoo’s confidential information to LAS Tech, and LAS Tech accepted used that information to pursue claims against Yahoo. (Id. at p. 3:8-20.)

In opposition, Yahoo argues that absent any express allegations of trade secret misappropriation, the claims are not preempted by CUTSA. Yahoo further contends that the causes of action are based on facts independent of any alleged trade secret misappropriation because the claims, in part, are based LAS Tech’s hiring of Avner. 1 This argument was raised for the first time in LAS Tech’s reply. This new argument should have been made LAS Tech’s moving papers, and its attempt to raise the argument for the first time in reply is improper. Such arguments are ordinarily disregarded because other party is deprived of the opportunity to counter the argument. (See Reichardt v. Hoffman (1997) 52 Cal.App.4th 754, 764 [points raised for first time in a reply brief will ordinarily be disregarded because other party is deprived of the opportunity to counter the argument]; see also In re Tiffany Y. (1990) 223 Cal.App.3d 298, 302-303; REO Broadcasting Consultants v. Martin (1999) 69 Cal.App.4th 489, 500.) However, Yahoo has requested that the Court consider its sur-reply, which addresses this new argument. Accordingly, the Court will consider LAS Tech’s new argument and Yahoo’s request to file, and have the Court consider, its sur-reply is GRANTED. To the extent the claims are based on LAS Tech’s receipt and/or use of Yahoo’s confidential information, they are preempted by CUTSA. “CUTSA provides the exclusive civil remedy for conduct falling within its terms, so as to supersede other civil remedies ‘based upon misappropriation of a trade secret.’ ” (Silvaco Data Systems v. Intel Corp. (2010) 184 Cal. App. 4th 210, 236, citing Civ. Code, § 3426.7; Angelica Textile Services, Inc. v. Park (2013) 220 Cal.App.4th 495, 505 (Angelica) [“a prime purpose of the [CUTSA] was to sweep away the adopting states’ bewildering web of rules and rationales and replace it with a uniform set of principles for determining when one is—and is not—liable for acquiring, disclosing, or using information ... of value.”].) A cause of action is displaced where the cause of action is “based on the same nucleus of facts as the misappropriation of trade secrets claim for relief.” (K.C. Multimedia, Inc. v. Bank of America Technology & Operations, Inc. (2009) 171 Cal.App.4th 939, 955, internal citations omitted.) Furthermore, CUTSA preempts claims based on the misappropriation of confidential and/or proprietary information, whether or not that information meets the statutory definition of trade secret. (See Mattel, Inc. v. MGA Entertainment, Inc. (2010) 782 F.Supp.2d 911, 987; see also Loop AI Labs Inc v. Gatti (N.D. Cal. 2015) 2015 WL 5158461, at *3 [“the Court agrees with the vast majority of courts that have addressed this issue, and finds that CUTSA supersedes claims based on the misappropriation of information that does not satisfy the definition of trade secret under CUTSA, absent a property interest conferred on that information by some other provision of law”].) Here, the fifth, sixth, eleventh, and twelfth causes of action are based, in part, on allegations that LAS Tech obtained and/or used (i.e., misappropriated) Yahoo’s confidential information. (See SAC, ¶¶ 113, 119, 150, 158.) To the extent these claims are based on such allegations, they are preempted by CUTSA.

However, CUTSA does not displace claims that are related to trade secret misappropriation, but are “independent and based on facts distinct from the facts that support the misappropriation claim.” (Angelica, supra, 220 Cal.App.4th at pp. 499, 506.) Here, the fifth through twelfth causes of action are also based on allegations that LAS Tech hired Avner and LAS Tech encouraged Avner not to assist Yahoo. (SAC, ¶¶113, 119, 126, 131-32, 138-39, 145-46, 150, 158.) Thus, the claims are based, in part, “on facts [independent] [and] distinct from the facts that support the misappropriation claim,” i.e., the alleged receipt and use of Yahoo’s confidential information. (Angelica, supra, 220 Cal.App.4th at p. 499.)

Thus, LAS Tech’s argument fails to dispose of the claims in their entirety.

C. Litigation Privilege

LAS Tech contends that the litigation privilege bars all of Yahoo’s claims because “the conduct underlying each and every cause of action in the SAC is LAS Tech’s investigation and preparation to file suit against Yahoo.” (Mem. Ps. & As., p. 7:3-4.) LAS Tech initially focuses on the allegation in the SAC that it sent Yahoo a demand letter in June 2016, and asserts that demand letters fall within the privilege. (Id. at p. 7:4-8.) LAS Tech then points out that Yahoo allegedly discovered that it was working with Avner “during negotiations relating to the claims made in LAS Tech’s demand letter ….” (Id. at p.7:11-13.) Next, LAS Tech asserts that any alleged communications between it and Avner are privileged and, therefore, and claims based on alleged disclosures of Yahoo confidential information are barred by the privilege. (Id. at p. 7:16-19.) Finally, LAS Tech contends that any non-communicative conduct is related to its “communicative, pre-litigation preparations” and, thus, is privileged. (Id. at p. 9:4-14.) LAS Tech’s arguments are not well-taken. “[T]he [litigation] privilege applies to any communication (1) made in judicial or quasi-judicial proceedings; (2) by litigants or other participants authorized by law; (3) to achieve the objects of the litigation; and (4) that have some connection or logical relation to the action.” (Silberg v. Anderson (1990) 50 Cal.3d 205, 212; see Civ. Code, § 47.) The communications identified by LAS Tech are Yahoo’s demand letters, statements made by the parties during negotiations, and communications between LAS Tech and Avner. However, the claims as alleged against LAS Tech are not based on statements in Yahoo’s demand letter or on statements made by the parties during negotiations. The statements in Yahoo’s demand letter and the statements made during the parties’ negotiations are merely background information. Instead, Yahoo’s claims are primarily based on LAS Tech’s hiring of Avner and its acceptance and/or use of Yahoo’s confidential information. The gravamen of the claims, as alleged against LAS Tech, is not that Yahoo’s alleged injury was occasioned simply by Avner’s disclosure of confidential information (which is undeniably a communication), but rather that Yahoo has been injured by LAS Tech’s non-communicative conduct—its acceptance and use of Yahoo’s confidential information and its hiring of Avner. (See Kimmel v. Goland (1990) 51 Cal.3d 202, 211 [distinguishing between injury allegedly arising from communicative acts and injury resulting from noncommunicative conduct].) Consequently, LAS Tech has not demonstrated that the litigation privilege bars the fifth through twelfth causes of action.

D. LAS Tech’s Knowledge of the Separation Agreement

Lastly, LAS Tech contends that “Yahoo’s Separation Agreement claims also fail because the Opposition fails to provide any evidence that [it] knew of the existence of the Separation Agreement or that the hiring of Avner and instruction that he not cooperate with Yahoo would result in a breach of the Agreement.” (Reply, p. 4:1-4.)

As Yahoo persuasively argues, LAS Tech fundamentally misunderstands the pleading requirements. Yahoo is not required to plead evidentiary facts supporting its allegation that LAS Tech was aware of the Separation Agreement. (See C.A. v. William S. Hart Union High School Dist. (2012) 53 Cal.4th 861, 872 [in general, the pleading need only allege ultimate facts in stating a cause of action]; see also Ferrick v. Santa Clara University (2014) 231 Cal.App.4th 1337, 1341 [a plaintiff need not allege “‘each evidentiary fact that might eventually form part of the plaintiff’s proof’ ”].) Therefore, LAS Tech’s argument lacks merit.

E. Conclusion

For these reasons, LAS Tech’s demurrer to the fifth through twelfth causes of action is OVERRULED.

- oo0oo - Calendar line 4

- oo0oo - Calendar line 5

Case Name: Vidal Preciado v. Bank Of America, N.A., et al. Case No.: 17CV315401

This is an action alleging wrongful foreclosure and other claims brought by Pro per Plaintiff Vidal Preciado (“Plaintiff”) against several defendants. The claims concern real property located at 1343 State Street, San Jose 95002 (“Subject Property”). Currently before the Court is the demurrer to Plaintiff’s complaint brought by Defendants Bank of America, N.A., Recontrust Company, N.A., Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc., and The Bank of New York Mellon fka The Bank of New York as trustee for the Benefit of the Certificate Holders of the CWALT Inc. Alternative Loan Trust 2005-59, Mortgage Pass Through Certificates, Series 2005-59 (collectively “Defendants”). The Complaint Plaintiff states claims for: 1) “Improper and Imperfect Title”; 2) Violation of Civil Code § 2923.5; 3) Violation of Business and Professions Code § 17200; 4) “Unlawful Possession” (wrongful foreclosure); 5) “mortgage fraud,” and; 6) Promissory Estoppel.

Request for Judicial Notice A precondition to judicial notice in either its permissive or mandatory form is that the matter to be noticed be relevant to the material issue before the Court. (Silverado Modjeska Recreation and Park Dist. v. County of Orange (2011) 197 Cal.App.4th 282, 307, citing People v. Shamrock Foods Co. (2000) 24 Cal.4th 415, 422 fn. 2.)

In support of their demurrer, Defendants have submitted a request for the Court to take judicial notice of five documents (exhibits A-E to the request): 1) A copy of a Deed of Trust executed by Plaintiff which encumbered the subject property and was recorded in Santa Clara County on June 27, 2005 (Ex. A); 2) A copy of a Trustee’s Deed Upon Sale for the subject property, recorded in Santa Clara County on August 8, 2011, showing that pursuant to the Deed of Trust the subject property was foreclosed upon and sold on July 25, 2011 (Ex. B); 3) A copy of Plaintiff’s Complaint in case no. 2013-1-CV-250011, filed July 24, 2013, which named as defendants all of the presently demurring Defendants (Ex. C); 4) A slip copy of the Sixth District Court of Appeal’s November 30, 2016 unpublished decision in Preciado v. Bank of America, et al. (2016) 2016 WL 6996262, in which it affirmed the trial court’s dismissal of Plaintiff’s action in case no. 2013-1-CV-250011 (Ex. D), and; 5) A copy of a printout of the docket of the California Supreme Court as of October 5, 2017, showing that Plaintiff’s petition for review of the Sixth District’s decision had been denied as of that date (Ex. E).

Notice of all five documents is GRANTED pursuant to Evidence Code §§ 452(c) and (d). Exhibits C, D and E are noticed pursuant to Evidence Code § 452(d) as court records. The Court of Appeal’s decision is noticed as to its contents and legal effect. Exhibits A and B are noticed pursuant to Evidence Code § 452(c), which states the court may take judicial notice of “any official acts of the legislative, executive, and judicial departments of the United States and of any state of the United States.” This has been interpreted to include documents recorded by a government department. “The court may take judicial notice of recorded deeds.” (Evans v. California Trailer Court, Inc. (1994) 28 Cal.App.4th 540, 549. See also Fontenot v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. (2011) 198 Cal.App.4th 256, 264-65 [stating that “a court may take judicial notice of the fact of a document’s recordation, the date the document was recorded and executed, the parties to the transaction reflected in a recorded document, and the document’s legally operative language . . . [and, f]rom this, the court may deduce and rely upon the legal effect of the recorded document.”])

Demurrer to the Complaint In ruling on a demurrer the Court treats it “as admitting all material facts properly pleaded, but not contentions, deductions or conclusions of fact or law.” (Piccinini v. Cal. Emergency Management Agency (2014) 226 Cal.App.4th 685, 688, citing Blank v. Kirwan (1985) 39 Cal.3d 311, 318.) “A demurrer tests only the legal sufficiency of the pleading. It admits the truth of all material factual allegations in the complaint; the question of plaintiff’s ability to prove these allegations, or the possible difficulty in making such proof does not concern the reviewing court.” (Committee on Children’s Television, Inc. v. General Foods Corp. (1983) 35 Cal.3d 197, 213-214.) Allegations are not accepted as true on demurrer if they contradict or are inconsistent with facts judicially noticed. (See Cansino v. Bank of America (2014) 224 Cal.App.4th 1462, 1474 [rejecting allegation contradicted by judicially noticed facts].)

Defendants demur to all of Plaintiff’s causes of action on the ground that they fail to state sufficient facts because they are all barred by the res judicata effect of the dismissal of case no. 2013-1-CV-250011, as upheld by the Court of Appeal.

A general demurrer lies where the facts alleged in the complaint or matters judicially noticed show that a plaintiff’s claim is barred by res judicata or collateral estoppel. (Boeken v. Philip Morris USA, Inc. (2010) 48 Cal.4th 788, 792 (“Boeken”).) Res judicata, i.e. claim preclusion, “prevents relitigation of the same cause of action in a second suit between the same parties” and “arises if a second suit involves: (1) the same cause of action (2) between the same parties (3) after a final judgment on the merits in the first suit.” (DKN Holdings LLC v. Faerber (2015) 61 Cal.4th 813, 824 (“DKN Holdings”).) “When a matter is within the ‘scope of the [prior] action, related to the subject matter and relevant to the issues, so that it could have been raised, the judgment is conclusive on it.... Hence the rule is that the prior judgment is res judicata on matters which were raised or could have been raised, on matters litigated or litigable....’” (Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco v. Countrywide Financial Corporation (2013 214 Cal.App.4th 1520, 1529, internal citation omitted.) “Claim preclusion, the ‘ ‘primary aspect’ ’ of res judicata, acts to bar claims that were, or should have been, advanced in a previous suit involving the same parties.” (DKN Holdings, supra, at p. 824, citation omitted.)

Defendants’ demurrer to all six of Plaintiff’s present claims on res judicata/claim preclusion grounds is SUSTAINED as the complaint and the judicially noticed material establishes that all of the elements of res judicata have been satisfied. All of the parties in the present action were parties in the 2013 action. The 2013 action ended at the trial court level with a dismissal of the complaint with prejudice after defendants’ demurrer was sustained without leave to amend and “for purposes of applying the doctrine of res judicata . . . a dismissal with prejudice is the equivalent of a final judgment on the merits.” (Boeken, supra, at p. 792.) The trial court’s dismissal was affirmed by the Court of Appeal. The judicially noticed material also makes clear that all of Plaintiff’s present claims were or could have been could have been raised in the 2013 action. The 2013 complaint expressly alleged claims for Quiet Title and Slander of Title, Violation of Business and Professions Code § 17200, Wrongful Foreclosure, Fraud (during foreclosure) and promissory estoppel, among others, all based on the same foreclosure and sale of the subject property as the present action. While the 2013 complaint did not allege a violation of Civil Code § 2923.5 as a separate cause of action the Court of Appeal noted that, in attempting to defend his § 17200 claim, “plaintiff shifts to a new theory: that he ‘suffered injury based on Respondent’s [sic] violation of [Civil Code section] 2923.5.’ But plaintiff neither alleged specific conduct amounting to a violation of that statute nor explains on appeal what that conduct was and how it constituted a violation of the UCL. . . . In neither the complaint nor his appellate brief has plaintiff set forth the nature of any defendant’s failure to comply with the provisions of Civil Code section 2923.5.” (See Defendants’ RJN, Exhibit D, at pp. 19-20.) Therefore that cause of action in the present Complaint is also barred by the res judicata effect of the 2013 action.

The Court notes that Plaintiff’s opposition offers no response to Defendants’ res judicata argument or any explanation as to how the Complaint could be amended to state claims not barred by res judicata. Accordingly, leave to amend is DENIED. (See Jenkins v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. (2013) 216 Cal.App.4th 497, 535 [court should deny leave to amend where the facts are not in dispute and no liability exists under substantive law]; Medina v. Safe-Guard Products (2008) 164 Cal.App.4th 105, 112 fn. 8 [“As the Rutter practice guide states: ‘It is not up to the judge to figure out how the complaint can be amended to state a cause of action. Rather, the burden is on the plaintiff to show in what manner he or she can amend the complaint, and how that amendment will change the legal effect of the pleading.’”])

- oo0oo - Calendar line 6

Case Name: Doe. v.Go Kids, Inc., et al. Case No.: 2016-1-CV-298548

Before the Court is the motion for summary judgment/summary adjudication brought by Defendant, Go Kids, Inc.

After full consideration of the evidence, the separate statements submitted by the parties, and the authorities submitted by each party, the court makes the following findings and order.

According to the allegations of the complaint, between April 2014 and mid-June 2014, six-year old plaintiff Jane Doe (“Plaintiff”) was sexually molested by defendant Alberto Ramirez (“Alberto”), the husband of defendant Josefina Ramirez (“Josefina”), with the assistance of Josefina and Josefina Ramirez Family Day Care (“Day Care”). (See complaint, ¶¶ 2-6, 10.) Defendant Go Kids, Inc. (“Go Kids”) contracts with licensed day care providers to provide child care services, claiming to provide quality assurance, training, technical support and monthly home visit consultations in order to provide quality care. (See complaint, ¶ 2.) On April 11, 2014, Go Kids arranged for Doe to be provided day care services performed by Josefina and Day Care. (See complaint, ¶ 2.) After learning from a July 2015 news broadcast that Alberto was arrested for multiple counts of lewd acts upon a child, and that Doe told her mother that Alberto also touched her, on August 15, 2016, Plaintiff, a minor, by and through her Guardian ad Litem, Raquel Doe, filed a complaint against defendants Go Kids, Josefina, Alberto and Day Care, asserting causes of action for: sexual abuse of a minor; negligence; and, intentional infliction of emotional distress. The lone cause of action against Go Kids is for negligence.

Go Kids moves for summary judgment, or, in the alternative, for summary adjudication of issues of duty.

Defendant Go Kids, Inc.’s Motion For Summary Judgment, Or In The Alternative, For Summary Adjudication

Defendant’s burden on summary judgment

“A defendant seeking summary judgment must show that at least one element of the plaintiff’s cause of action cannot be established, or that there is a complete defense to the cause of action. … The burden then shifts to the plaintiff to show there is a triable issue of material fact on that issue.” (Alex R. Thomas & Co. v. Mutual Service Casualty Ins. Co. (2002) 98 Cal.App.4th 66, 72; internal citations omitted; emphasis added.)

“The ‘tried and true’ way for defendants to meet their burden of proof on summary judgment motions is to present affirmative evidence (declarations, etc.) negating, as a matter of law, an essential element of plaintiff’s claim.” (Weil et al., Cal. Practice Guide: Civil Procedure Before Trial (The Rutter Group 2007) ¶ 10:241, p.10-91, citing Guz v. Bechtel National Inc. (2000) 24 Cal.4th 317, 334; emphasis original.) “The moving party’s declarations and evidence will be strictly construed in determining whether they negate (disprove) an essential element of plaintiff’s claim ‘in order to avoid unjustly depriving the plaintiff of a

trial.’” (Id. at § 10:241.20, p.10-91, citing Molko v. Holy Spirit Assn. (1988) 46 Cal.3d 1092, 1107.)

“Another way for a defendant to obtain summary judgment is to ‘show’ that an essential element of plaintiff’s claim cannot be established. Defendant does so by presenting evidence that plaintiff ‘does not possess and cannot reasonably obtain, needed evidence’ (because plaintiff must be allowed a reasonable opportunity to oppose the motion.) Such evidence usually consists of admissions by plaintiff following extensive discovery to the effect that he or she has discovered nothing to support an essential element of the cause of action.” (Id. at ¶ 10:242, p.10-92, citing Aguilar v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (2001) 25 Cal.4th 826, 854- 855.)

Go Kids may not seek adjudication of “issues” that are not issues of duty absent a stipulation pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 437c, subdivision (t).

Go Kids moves for summary judgment, and in the alternative, moves for summary adjudication of four “issues.” The first issue is that Go Kids cannot be liable for negligence because it does not have a duty to protect against an unforeseen criminal assault. The second through fourth issues regarding vicarious liability and nondelegable duties are not “issues of duty” pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 437c, and thus require a stipulation pursuant to subdivision (t). Go Kids does not present such a stipulation. The motion for summary adjudication of the second through fourth purported issues are DENIED.

Go Kids meets its initial burden to demonstrate that it did not owe Plaintiff a legal duty to protect an unforeseen criminal assault

Go Kids argues that Plaintiff cannot demonstrate that Go Kids owed her a legal duty, relying on J.L. v. Children’s Institute, Inc. (2009) 177 Cal.App.4th 388. In J.L., supra, nonprofit corporation Children’s Institute Inc. (“CII”) had a master contract with the State of California to provide childcare services through its own licensed day care facilities for eligible families, and also contracted with 45 day care homes to which eligible families may be referred. (Id. at p.391.) The family day care homes with whom CII contracted were required to be licensed with the Department of Social Services Community Care Licensing. (Id.) CII’s case manager visited the home twice monthly. (Id. at p.392.) During the period of time between plaintiff’s initial visit with the home and the molestation of the victim, the file did not indicate that there were any reports or observations of problems at the home. (Id.) Before the molestation, the plaintiff expressed concern of the presence of two male adults present at the home, and the contractee/licensee indicated that they were her grandchildren and assured the plaintiff that they would remain outside doing mechanical work and that individuals needed to be authorized to be present at the home. (Id. at pp.392-393.) A month later, the plaintiff saw a 14-year old boy playing with things inside the day care area, and expressed concern to CII’s case manager. (Id. at p.393.) CII’s case manager personally observed the boy at the home and asked the contractee/licensee regarding his presence, to which the contractee/licensee responded that the boy was her grandson who was on vacation. (Id.) CII’s case manager observed that the boy was present at some but not all of her subsequent visits to the home, was never near any of the children as he was always in the garage or backyard, and was neither suspicious nor concerned by the boy’s presence as she never observed or received a report about a lack of supervision by the contractee/licensee or any inappropriate behavior by the boy, the case manager never received any information indicating that the boy had a history of sexual

abuse, and the victim referred to the boy as his friend. (Id.) In affirming the trial court’s granting of summary judgment, the J.L. court stated:

… Although appellant has repeatedly maintained that it was foreseeable something “bad” would happen because E.Y. was in the house, he proffered no evidence suggesting that E.Y. had a history of sexual misconduct or that CII was aware of any such history. Indeed, there was no evidence suggesting that any child had suffered any type of injury in the Yglesias home prior to the attack on appellant. Nor did appellant offer evidence that any type of criminal or violent incident had previously occurred in the Yglesias home. Although Yglesias testified that E.Y. told her he had been in fights in school, there was no evidence that Yglesias had conveyed this information to CII. (See Romero v. Superior Court, supra, 89 Cal.App.4th at p. 1088, 107 Cal.Rptr.2d 801 [minor assailant’s history of misconduct irrelevant to the determination of duty because defendants were unaware of it]; accord, Margaret W., supra, 139 Cal.App.4th at p. 158, fn. 22, 42 Cal.Rptr.3d 519.) Because there was no evidence showing CII had actual knowledge of E.Y.'s assaultive tendencies or that he posed any risk of harm, his conduct was not foreseeable and CII owed no duty to protect against the attack.

… Here … appellant proffered no evidence showing that CII maintained or was aware of Yglesias maintaining any problem area in her home making the possibility of an assault reasonably foreseeable. The undisputed evidence established that the attack on appellant was unforeseeable.

The J.L. court also noted that the plaintiff’s theories regarding vicarious liability based on a breach of a nondelegable duty or a theory of ostensible agency lacked merit. (Id. at pp. 400-407.)

In support of its motion, Go Kids presents evidence similarly demonstrating that it was not actually aware of Alberto’s history of sexual misconduct or any type of prior criminal or violent incidents at Day Care until July 14, 2015 when Alberto was arrested for sexual abuse. (See Def.’s separate of undisputed material facts in support of motion for summary judgment, nos. (“UMFs”) 1-48.) However, unlike the situation in J.L., supra, Go Kids apparently concedes that there is evidence that Alberto had a history of sexual misconduct at Day Care; however, it asserts that it did not know about that history. A declaration from Kendra Bobsin states that “[a]fter this lawsuit was filed, [she] learned of a May 30, 2014 Child Care Licensing Facility Evaluation Report pertaining to a November 2013 complaint of sexual abuse regarding Day Care, but that neither Josefina nor Child Care Licensing provided the evaluation report to Go Kids, and thus Go Kids did not know of the existence of that report. (See Bobsin decl., ¶ 25.) Go Kids meets its initial burden to demonstrate that the cause of action for negligence lacks merit against it for lack of a legal duty owed by Go Kids to Plaintiff.

In opposition, Plaintiff demonstrates the existence of a triable issue of material fact.

In opposition to the motion, Plaintiff presents deposition testimony from Josefina who stated that: on May 30, 2014, she signed the report indicating sexual abuse by Alberto; an employee from Go Kids, Angelica Munoz, visited her home on June 12, 2014; the report was posted at the time of the visit; and she gave/showed the report to Angelica Munoz and Mary, and told Maria in the office, but was told that they didn’t need it yet. (See Pl.s evidence, exh. 5 (“Josefina depo”), pp.45:16-24, 47:23-25, 48:1-16, 49:12-23, exh. 6.) Here, this evidence demonstrates the existence of a triable issue of material fact as to whether Go Kids knew, or were on notice of Alberto’s history of sexual misconduct.

In reply, Go Kids asserts that it is “[i]mmaterial” that it was provided the report because the report indicated that it was inconclusive as to whether the sexual abuse happened. (See Def.’s separate statement in response to Pl.’s additional material facts, no. 148.) As Angelica Martin stated, however, for purposes of the report, “inconclusive” means that although there is insufficient evidence to prove, it is “highly likely” that it occurred. (See Pl.’s evidence, exh. 4 (“Martin depo”), p.32:13-22.) The Court disagrees with Go Kids’ characterization that the complaint of sexual abuse is immaterial; on the contrary, the complaint of sexual abuse is highly relevant to the issue of whether Go Kids knew, or were on notice of Alberto’s history of sexual misconduct.

As Plaintiff demonstrates the existence of a triable issue of material fact, the motion for summary judgment, and the motion for summary adjudication of the issue of duty to protect against an unforeseen criminal assault is DENIED.

As Go Kids does not object to the above cited evidence, the Court need not rule on Go Kids’ other objections to evidence, as they are not material to the court’s decision. (Code of Civil Procedure §437c(q).)

- oo0oo -

Calendar lines 7 and 8

Case Name: Laura Wenke v. Susan W. Buchholz, Ph.D., et al. Case No.: 2013-1-CV-257720

Currently before the Court are the following matters: (1) the motion by defendant Susan W. Buchholz, Ph.D. (“Susan”) for summary judgment of the complaint of plaintiff Laura Wenke (“Plaintiff”) or, in the alternative, summary adjudication of the first cause of action for professional negligence; and (2) the joinder in Susan’s motion by defendant William M. Buchholz, M.D. (“William”).2

Factual and Procedural Background

This is a medical malpractice action arising out of psychological treatment provided to Plaintiff by Susan and William (collectively, “Defendants”). (Complaint, ¶¶ 2-3, 6.) Susan is a licensed clinical psychologist engaged in the practice of providing psychotherapeutic and/or medical treatment. (Id. at ¶ 2.) William is a physician engaged in the practice of medicine. (Id. at ¶ 3.)

From approximately February 2011 through September 14, 2011, Defendants provided “psychotherapeutic and medical examinations and treatment to Plaintiff for anxiety and depression, said treatment including but not limited to prescribing and monitoring medications known as Lexapro and Ativan.” (Complaint, ¶ 6.) Plaintiff’s use of Lexapro and Ativan allegedly “put her into a bizarre, dissociated, and violence-prone psychological state on September 15, [2011], during which she unconsciously and unknowingly attacked and stabbed her estranged husband with a knife, causing him serious injuries.”3 (Id. at ¶ 7.) Consequently, Plaintiff “was immediately incarcerated on criminal charges, and currently remains incarcerated thereon.” (Ibid.)

Plaintiff alleges that Susan “acted negligently in the course of providing psychotherapeutic and/or medical examinations and treatment to [her], which negligence including but not limited to the failure of [Susan] to exercise due care in recommending and monitoring [her] usage of Lexapro and Ativan.” (Complaint, ¶ 9.) Plaintiff further alleges that William “acted negligently in the course of providing medical examinations and treatment to [her]” by failing “to exercise due care in prescribing and monitoring [her] usage of Lexapro and Ativan.” (Id. at ¶ 16.) As the proximate result of Defendants’ alleged negligence, Plaintiff suffered damages, including expenses relating to health care treatment, loss of earnings, loss of earning capacity, pain, suffering, mental anguish, loss of liberty and “limitations in her enjoyment of life.” (Id. at ¶¶ 10-12 and 17-19.)

On December 13, 2013, Plaintiff filed the complaint against Defendants, alleging causes of action for: (1) professional negligence (against Susan); (2) professional negligence (against William); and (3) negligence (against Doe defendants).

2 At times, the parties are referred to by their first names for purposes of clarity; no disrespect is intended. (See Rubenstein v. Rubenstein (2000) 81 Cal.App.4th 1131, 1136, fn. 1.) 3 The complaint identifies the date of the attack as September 15, 2012, but this appears to be a typographical error.

On September 25, 2017, Susan filed the instant motion for summary judgment of the complaint or, alternatively, summary adjudication of the first cause of action for professional negligence. The following day, William filed a notice of joinder in Susan’s motion, memorandum of points and authorities, and separate statement. Plaintiff filed papers in opposition to both matters on November 30, 2017.4 On December 8, 2017, Susan filed a reply in support of her motion. Subsequently, on December 11, 2017, William filed a reply in support of his joinder.

Discussion

I. William’s Joinder

In his notice of joinder, Williams states that he “hereby joins in [Susan’s] Motion for Summary Judgment, or in the Alternative, Summary Adjudication ….” (Joinder, p. 1:21-23.) He further states that he “incorporates by reference any and all pleadings, declarations and supporting papers filed and served in support thereof.” (Id. at p. 1:24-26.) In his memorandum of points and authorities, William asserts that he “now moves for summary judgment based on the collateral estoppel effect of the criminal proceeding barring Plaintiff from re-litigating her contention that she is not responsible for her planned, premeditated, and intentional assault on [her then husband].” (Id. at p. 2:14-17.) William “requests the court grant his motion for summary judgment on the grounds that Plaintiff’s claims are precluded by collateral estoppel because the criminal verdicts have been affirmed.” (Id. at p. 6:11-13.) William also submits a separate statement of undisputed material facts (“UMF”), setting forth eight UMF. However, William does not himself submit any evidence in support of his UMF. Notably, the evidence cited in William’s separate statement in support of his UMF is: Plaintiff’s complaint; documents of which Susan requested judicial notice; and some of Susan’s UMF. (William’s Sep. Stmt., pp. 2-4.)

Code of Civil Procedure section 437c, subdivision (b)(1) states that a party moving for summary judgment or summary adjudication must support the motion with affidavits, declarations, and other discovery materials. (Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (b)(1); Frazee v. Seely (2002) 95 Cal.App.4th 627, 636; Village Nurseries, L.P. v. Greenbaum (2002) 101 Cal.App.4th 26, 46.) “In order to establish a prima facie case for summary judgment, a moving party defendant must present admissible evidence establishing a complete defense to the claim or that plaintiff will be unable to prove an essential element of the claim. [Citation.] Only then is the opposing party required to present admissible evidence in opposition. [Citation.] When a party merely joins in a motion for summary judgment without presenting its own evidence, the

4 Susan filed a notice of non-opposition on December 4, 2017, stating that her counsel had not received the opposition papers as of noon that day and the Court should, consequently, consider her motion to be unopposed. Susan cites no legal authority supporting her position that the Court should consider the matter unopposed simply because her counsel did not received the papers as of December 4, 2017. (See Badie v. Bank of America (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 779, 784-785; see also Schaeffer Land Trust v. San Jose City Council (1989) 215 Cal.App.3d 612, 619, fn. 2 [“[A] point which is merely suggested by a party’s counsel, with no supporting argument or authority, is deemed to be without foundation and requires no discussion.”].) Furthermore, the proof of service filed with Plaintiff’s opposition papers states that the documents were served by express mail on November 30, 2017, and to be delivered to Susan’s counsel by overnight delivery. Thus, Plaintiff properly served her opposition papers on Susan. (See Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (b)(2) [“An opposition to the motion shall be served and filed not less than 14 days preceding the noticed or continued date of hearing, unless the court for good cause orders otherwise.”].)

party fails to establish the necessary factual foundation to support the motion.” (Barak v. Quisenberry Law Firm (2006) 135 Cal.App.4th 654, 661, italics added.)

Here, William failed to present any evidence, instead merely stating that he “incorporates by reference any and all pleadings, declarations and supporting papers filed and served in support thereof.” (p. 1:24-26.) Accordingly, William’s request for joinder is DENIED.

II. Susan’s Motion for Summary Judgment or, Alternatively, Summary Adjudication

Under Code of Civil Procedure section 437c, Susan moves for summary judgment of the complaint or, in the alternative, summary adjudication of the first cause of action for professional negligence on the grounds that:

Plaintiff cannot establish that any act or omission on [her] part … was a substantial factor in causing [Plaintiff] to attack her estranged husband and sustain any “injury” including incarceration for the attack. More specifically, … [Plaintiff] was deemed by a jury in the criminal proceeding entitled The People of the State of California v. Laura Jean Wenke, San Mateo County Superior Court Case No. SC-075652A, to have been sane and acting willfully, deliberately and with premeditation in the attempted murder of her husband, Randall Wenke, on September 15, 2011[,] such that the doctrine of collateral estoppel precludes her from re-litigating the issue of whether Plaintiff “unconsciously and unknowingly attacked and stabbed her estranged husband with a knife, causing him serious injuries.” (Plaintiff’s Complaint, ¶ 7, 2:15-18.) The specific causation issue presented in this action, to wit, whether Plaintiff’s medications caused her to “unconsciously and unknowingly” attack and stab her estranged husband, was presented to the criminal jury through medical expert testimony and specifically rejected. This issue having been litigated and decided, collateral estoppel precludes re-litigation of the element of causation.

(Susan’s Ntc. Mtn., p. 2:2-17.)

A. Nature of the Motion

Though Susan states that she is moving for summary judgment or, alternatively, summary adjudication, the only claim alleged against Susan in the complaint is the first cause of action for professional negligence. Thus, in actuality, Susan simply seeks summary judgment of the complaint, as alleged against her, as her motion with respect to the first cause of action for professional negligence, if successful, would dispose of the lawsuit in its entirety. Consequently, the Court construes the instant motion as one for summary judgment alone.

B. Request for Judicial Notice

Susan asks the Court to take judicial notice of the following items: a certified copy of the Information filed in the matter of The People of the State of California v. Laura Jean Wenke (San Mateo County Superior Court, Case No. SC-075652A) (the “Criminal Case”);

certified copies of nine Phase I Verdicts filed in the Criminal Case; certified copies of four Phase II Verdicts filed in the Criminal Case; the unpublished decision of the First District Court of Appeal in People v. Wenke (Cal. Ct. App., Mar. 17, 2016, No. A142905) 2016 WL 1056777;5 portions of the reporter’s transcript of proceedings from the trial in the Criminal Case; a certified copy of the First District Court of Appeal docket in the Criminal Case; and a certified copy of the Abstract of Judgment—Prison Commitment—Indeterminate filed in the Criminal Case.

Each of these items is a court record that is relevant to the pending motion. Evidence Code section 452, subdivision (d) states that the court may take judicial notice of “[r]ecords of any court of this state.” That provision permits the trial court to “take judicial notice of the existence of judicial opinions and court documents, along with the truth of the results reached —in the documents such as orders, statements of decision, and judgments—but [the court] cannot take judicial notice of the truth of hearsay statements in decisions or court files, including pleadings, affidavits, testimony, or statements of fact.” (People v. Woodell (1998) 17 Cal.4th 448, 455.)

Accordingly, Susan’s request for judicial notice is GRANTED as to the existence of the court records and the truth of the results reach in documents such as orders, statements of decision, and judgments. (See Rodgers v. Sargent Controls & Aerospace (2006) 136 Cal.App.4th 82, 90 [“To determine whether to preclude relitigation on collateral estoppel grounds, judicial notice may be taken of a prior judgment and other court records.”].)

C. Legal Standard on Motions for Summary Judgment

The pleadings limit the issues presented for summary judgment and such a motion may not be granted or denied based on issues not raised by the pleadings. (See Government Employees Ins. Co. v. Super. Ct. (2000) 79 Cal.App.4th 95, 98; Laabs v. City of Victorville (2008) 163 Cal.App.4th 1242, 1258; Nieto v. Blue Shield of Calif. Life & Health Ins. (2010) 181 Cal.App.4th 60, 73 [“the pleadings determine the scope of relevant issues on a summary judgment motion”].)

A motion for summary judgment must dispose of the entire action. (Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (a).) “Summary judgment is properly granted when no triable issue of material fact exists and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. A defendant moving for summary judgment bears the initial burden of showing that a cause of action has no merit by showing that one or more of its elements cannot be established or that there is a complete defense. Once the defendant has met that burden, the burden shifts to the plaintiff ‘to show that a triable issue of one or more material facts exists as to that cause of action or a defense thereto.’ ‘There is a triable issue of material fact if, and only if, the evidence would allow a reasonable trier of fact to find the underlying fact in favor of the party opposing the motion in accordance with the applicable standard of proof.’ ” (Madden v. Summit View, Inc. (2008) 165 Cal.App.4th 1267, 1272, internal citations omitted.)

5 Although the First District Court of Appeal’s decision in the Criminal Case is unpublished, it may be cited or relied on as the opinion is relevant under the doctrine collateral estoppel. (See Cal. Rules of Ct., rule 8.1115(b)(1) [“An unpublished opinion may be cited or relied on: (1) When the opinion is relevant under the doctrines of law of the case, res judicata, or collateral estoppel …”].)

For purposes of establishing their respective burdens, the parties involved in a motion for summary judgment must present admissible evidence. (Saporta v. Barbagelata (1963) 220 Cal.App.2d 463, 468.) Additionally, in ruling on the motion, a court cannot weigh said evidence or deny summary judgment on the ground that any particular evidence lacks credibility. (See Melorich Builders v. Super. Ct. (1984) 160 Cal.App.3d 931, 935; see also Lerner v. Super. Ct. (1977) 70 Cal.App.3d 656, 660.) As summary judgment “is a drastic remedy eliminating trial,” the court must liberally construe evidence in support of the party opposing summary judgment and resolve all doubts concerning the evidence in favor of that party. (See Dore v. Arnold Worldwide, Inc. (2006) 39 Cal.4th 384, 389; see also Hepp v. Lockheed-California Co. (1978) 86 Cal.App.3d 714, 717-718.)

D. General Law Regarding Causation in Medical Malpractice Claims

“The elements of a cause of action for medical malpractice are: (1) a duty to use such skill, prudence, and diligence as other members of the profession commonly possess and exercise; (2) a breach of the duty; (3) a proximate causal connection between the negligent conduct and the injury; and (4) resulting loss or damage.” (Johnson v. Super. Ct. (2006) 143 Cal.App.4th 297, 305, citing Hanson v. Grode (1999) 76 Cal.App.4th 601, 606.) Thus, “[i]n a medical malpractice action, a plaintiff must prove the defendant's negligence was a cause-in- fact of injury.” (Jennings v. Palomar Pomerado Health Systems, Inc. (2003) 114 Cal.App.4th 1108, 1118 (Jennings).)

To show the element causation cannot be established in a medical malpractice action, the defendant must present expert testimony opining that the plaintiff’s injury was not “caused by anything that defendants did or failed to do. (Bushling v. Fremont Medical Center (2004) 117 Cal.App.4th 493, 508.) The test for proving causation in a medical malpractice case is the substantial factor test. (Mayes v. Bryan (2006) 139 Cal.App.4th 1075, 1092.) “Conduct can be considered a substantial factor in bringing about harm if it has created a force or series of forces which are in continuous and active operation up to the time of the harm, or stated another way, the effects of the actor’s negligent conduct actively and continuously operate to bring about harm to another.” (Id. at p. 1093, internal citations and quotation marks omitted.)

“Like breach of duty, causation also is ordinarily a question of fact which cannot be resolved by summary judgment. The issue of causation may be decided as a question of law only if, under undisputed facts, there is no room for a reasonable difference of opinion.” (Kurinij v. Hanna & Morton (1997) 55 Cal.App.4th 853, 864; see Capolungo v. Bondi (1986) 179 Cal.App.3d 346, 354 [“the issue of proximate cause ordinarily presents a question of fact. However, it becomes a question of law when the facts of the case permit only one reasonable conclusion.”]; see also Robison v. Six Flags Theme Parks Inc. (1998) 64 Cal.App.4th 1294, 1304, fn. 2 [causation is generally a factual issue for trial after the scope of duty (i.e., what precautionary measures were reasonably required) is determined].)

E. General Law Regarding the Doctrine of Collateral Estoppel

“Collateral estoppel (more accurately referred to as ‘issue preclusion’) ‘prevents relitigation of previously decided issues,’ even if the second suit raises different causes of action. [Citation.] Under California law, ‘issue preclusion applies (1) after final adjudication (2) of an identical issue (3) actually litigated and necessarily decided in the first suit and (4) asserted against one who was a party in the first suit or one in privity with that party.’

[Citation.] The issue preclusion bar ‘can be raised by one who was not a party or privy in the first suit.’ [Citation.]” (Kemper v. County of San Diego (2015) 242 Cal.App.4th 1075, 1088 (Kemper).)

“In deciding whether to apply collateral estoppel, the court must balance the rights of the party to be estopped against the need for applying collateral estoppel in the particular case, in order to promote judicial economy by minimizing repetitive litigation, to prevent inconsistent judgments which undermine the integrity of the judicial system, or to protect against vexatious litigation.” (Alvarez v. May Dept. Stores Co. (2006) 143 Cal.App.4th 1223, 1233.)

F. Susan’s Arguments and Evidence

Susan argues that Plaintiff cannot establish the element of causation (i.e., that any act or omission on her part was a substantial factor in causing Plaintiff’s damages) because the jury in the Criminal Case found Plaintiff to be sane and acting willfully, deliberately, and with premeditation when Plaintiff attempted to murder her husband on September 15, 2011. (Ntc. Mtn., 2:2-5.) Susan asserts that “[t]he specific causation issue [presented] in this action” is “whether Plaintiff’s medications caused her to ‘unconsciously and unknowingly’ attack and stab her estranged husband ….” (Ntc. Mtn., 2:12-15.) Susan states that this same issue “was presented to the criminal jury through medical expert testimony and specifically rejected.” (Ntc. Mtn., 2:14-16.) Susan contends that the doctrine of collateral estoppel, therefore precludes Plaintiff her from “re-litigating the issue of whether Plaintiff ‘unconsciously and unknowingly attacked and stabbed her estranged husband with a knife, causing him serious injuries.’ ” (Ntc. Mtn., 2:10-17; Mem. Ps. & As., p. 1:4-6.) In essence, Susan contends that the issue of causation presented in this case was previously litigated and necessarily decided in the Criminal Case against Plaintiff. (Mem. Ps. & As., p. 1:4-10.)

In support of her argument, Susan presents 177 UMF.6 As is relevant here, the UMF, and Susan’s supporting evidence, establish that the San Mateo District Attorney filed an Information against Plaintiff for attempting to murder Randall Wenke “willfully, unlawfully, and with malice aforethought” on September 15, 2011. (UMF Nos. 4-5; RJN, Ex. E.) Plaintiff was also charged with assault with a knife, assault with a stun gun or taser, and infliction of corporal injury. (UNF Nos. 4-8; RJN, Ex. D.) Plaintiff pleaded not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity. (RJN, Ex. D.)

In the first phase of the criminal trial, Plaintiff testified about the impact of the medications, Lexapro and Ativan, on her mental state. (UMF Nos. 16-21.) Plaintiff’s defense attorney presented expert testimony to the jury about: Plaintiff’s use of the medication; the affect starting and stopping those medications might have on a patient; the side effects of those medications; the affect that those medications might have had on Plaintiff’s mental state; the improper monitoring of Plaintiff’s use of the medications; the adverse effects that improper monitoring could have; the possibility that an unmonitored person taking such medications might develop a mental condition, like mania; and the reasonably probability that an untreated mental condition, as well as the administration of the medications, caused Plaintiff’s behavior

6 Many of these facts are evidentiary as opposed to material. (See Carlsen v. Koivumaki (2014) 227 Cal.App.4th 879, 884 [“The facts alleged or tendered in a summary judgment proceeding perform two different functions. As material facts they measure whether the plaintiff has alleged a cause of action. As evidentiary facts they establish whether the material facts have been proved.”].)

on September 15, 2011. (UMF Nos. 43-68 and 81-89.) The prosecutor cross-examined Plaintiff and the experts regarding the foregoing. (UMF Nos. 21, 28-36, 37-42, 59-63, 69-80.) The prosecutor also presented opposing expert witnesses who also testified about the effects and Plaintiff’s use of the medications. (Ibid.)

In closing argument, defense counsel argued that the medications could cause mental conditions; intoxication can include experiencing the side effects of medication; Plaintiff was not warned about the side effects of the medications she was taking; Plaintiff’s mental state worsened when she started and stopped the medication; Plaintiff was severely mentally ill; it was reasonably probable that the attack on Plaintiff’s husband was caused by Plaintiff’s mental disorder and use of the medications; the medications, along with Plaintiff’s mental disorder, could cause the specific intent to kill; and Plaintiff was involuntarily intoxicated due to the side effects of the medication. (UMF Nos. 128-138.) In closing, the prosecutor argued that even though the defense asserted that the use and improper monitoring of the medication usage was the cause of the attack, Plaintiff did not suffer the side effects described, she was not intoxicated, her reaction to the medication was not the cause of the attack, and she possessed the requisite mens rea. (UMF Nos. 123-124 and 139-147.)

The jury in the Criminal Case was then asked to decide Plaintiff’s mental state as part of the verdict, i.e., was the attempted murder committed willfully, deliberately, and with premeditation within the meaning of Penal Code section 189. (UMF Nos. 110-147.) The trial court explained that to convict Plaintiff of attempted murder the jury would need to find that the act was intentional, Plaintiff intended to kill, she weighed the considerations for and against her choice, and knowing the consequences decided to kill. (Ibid.) The trial court instructed the jury that a decision to kill made impulsively without careful consideration of the choice and its consequences is not premeditated and deliberate. (Ibid.) The trial court also instructed the jury regarding voluntary and involuntary intoxication. (Ibid.) The jury then found Plaintiff guilty of attempted murder, i.e., that she willfully, deliberately, and with premeditation attempted to kill Randall Wenke. (UMF Nos. 9-13 and 148-150; RJN, Ex. B.)

After Plaintiff was found guilty, the issue of Plaintiff’s sanity was tried. (UMF Nos. 151-168.) The defense presented expert testimony that Plaintiff was vulnerable to the medications; Susan improperly monitored Plaintiff’s medication usage; the way the drug was administered contributed to Plaintiff’s mental state; Plaintiff was insane; and Plaintiff fell into a dissociative state prior to the offense such that she was not capable of understanding that nature, quality, or wrongfulness of her actions during the attack. (UMF Nos. 151-162, RJN, Ex. D.) Plaintiff’s defense attorney argued that the failure to properly monitor Plaintiff’s usage of the drugs was the “spark or catalyst” of the attack while the prosecutor asserted that the medications did not alter Plaintiff’s mental state and the defense’s argument could not be believed (UMF Nos. 164-168.) The trial court instructed the jury to determine whether it was more likely than not Plaintiff was legally insane when she committed the crimes, i.e., she had a mental disease or defect and, because of that disease or defect, she was incapable of knowing or understanding the nature and quality of her acts or was incapable of knowing or understanding that her act was morally or legally wrong. (UMF Nos. 163.) The jury eventually found Plaintiff to be legally sane at the time of the attack. (UMF No. 169.)

Susan points out that Plaintiff appealed her conviction and the First District Court of Appeal affirmed the judgment. (UMF Nos. 170-175; RJN, Ex. D.) Plaintiff’s later attempts for

review of her conviction by the California Supreme Court and United States Supreme Court were denied. (UMF Nos. 175-176; RJN, Ex. CC.)

G. Susan Fails to Meet Her Initial Burden on Summary Judgment

In light of the foregoing, the Court finds that Susan fails to meet her initial burden on summary judgment because she has not met the “identical issue” requirement. The “ ‘identical issue’ requirement addresses whether ‘identical factual allegations’ are at stake in the two proceedings, not whether the ultimate issues or dispositions are the same. ([Citation.])” (Lucido v. Super. Ct. (1990) 51 Cal.3d 335, 342; see Evans v. Celotex Corp. (1987) 194 Cal.App.3d, 741, 745.) “To apply the collateral estoppel bar, the issue must have been raised and decided in the prior proceeding. [Citation.] But collateral estoppel applies ‘even if some factual matters or legal theories that could have been presented with respect to that issue were not presented.’ [Citation].” (Kemper v. County of San Diego (2015) 242 Cal.App.4th 1075, 1089.) “ ‘Accordingly, where the previous decision rests on a ‘different factual and legal foundation’ than the issue sought to be adjudicated in the case at bar, collateral estoppel effect should be denied.’ [Citations.] Precisely defining the issue previously decided and the one sought to be precluded is critical.” (Johnson v. GlaxoSmithKline, Inc. (2008) 166 Cal.App.4th 1497, 1513.)

As is relevant here, Susan’s evidence demonstrates that the jury in the Criminal Case was asked to decide (1) whether Plaintiff possessed the requisite mental state to commit attempted murder—i.e., whether the attempted murder committed willfully, deliberately, and with premeditation —and (2) whether she was insane—i.e., whether she had a mental disease or defect and, because of that disease or defect, she was incapable of knowing or understanding the nature and quality of her acts or was incapable of knowing or understanding that her act was morally or legally wrong. Plaintiff argued that she was insane and did not have the requisite mens rea, in part, because her medication usage altered her mental state. The jury rejected Plaintiff’s argument that she was insane and did not possess the requisite mental state. Thus, the factual issues actually litigated in the Criminal Case were whether Plaintiff’s medication usage altered her mental state such that she should be deemed insane and lacking the requisite mens rea.