JBM 16.5-6 Paper 165,10

An international perspective on luxury brand and country of origin effect1

Received in revised form 8th December 2008

Prof. Gaetano Aiello University of Florence - Italy Dr. Raffaele Donvito University of Florence - Italy Prof. Bruno Godey2 Rouen School of Management – France Prof. Daniele Pederzoli Rouen School of Management – France Prof. Klaus-Peter Wiedmann University of Hannover – Germany Dipl.-Oek. Nadine Hennigs University of Hannover – Germany Dipl.-Oek. Astrid Siebels University of Hannover – Germany Prof. Priscilla Chan The Hong Kong Polytechnic University – China Prof. Junji Tsuchiya Waseda University – Japan Prof. Samuel Rabino Northeastern University – USA Prof. Skorobogatykh Irina Ivanovna Plekhanov Russian Academy of Economics – Russia Dr. Bart Weitz University of Florida – USA Dr. Hyunjoo Oh University of Florida – USA Dr. Rahul Singh Birla Institute of Management Technology - Greater Noida – India

1 All the authors share the final responsibility for the contents of this article. However paragraph 1 was written by G. Aiello and R. Donvito; paragraph 2 was written by B. Godey, D. Pederzoli, R. Donvito and G. Aiello. All the authors co-wrote the introduction, paragraph 3 and the conclusion. 2 Contact author : Bruno Godey – Groupe ESC Rouen – Boulevard André Siegfried – BP 215 – 76825 Mont Saint Aignan cedex – France. : +33(0)232825760 – bruno.godey@groupe- esc-rouen.fr

1 - Prof. Gaetano Aiello – University of Florence – Italy Gaetano Aiello is full Professor of Marketing at the Faculty of Economics - University of Florence. His research interests include International Marketing and Firm Internationalization, Retail and Trade Marketing, Fashion Marketing, SME Marketing. - Dr. Raffaele Donvito – University of Florence – Italy Raffaele Donvito (PhD) is Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Faculty of Economics - University of Florence. His research interests include Retail Marketing, International Marketing, Fashion Marketing, and Communication. - Prof. Bruno Godey – Rouen School of Management – France Bruno Godey is Associate Professor of marketing at the Rouen School of Management. His research interests include consumer behaviour, brand and luxury marketing. - Prof. Daniele Pederzoli – Rouen School of Management – France Daniele Pederzoli is Associate professor of Marketing at the Rouen School of Management. His main research interests are retailing, internationalization and channel management. - Prof. Klaus-Peter Wiedmann – University of Hannover – Germany Klaus-Peter Wiedmann is full Professor and Director of the Institute of Marketing and Management at the Leibniz University of Hannover. His research interests include Strategic Marketing, International Marketing, Brand & Reputation Management, Consumer Behaviour, Corporate Culture & Change Management and Innovation & Technology Marketing. - Dipl.-Oek. Nadine Hennigs – University of Hannover – Germany Nadine Hennigs is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Marketing and Management at the Leibniz University of Hannover. Her research interests include Financial Services, Marketing & Management, Social Capital, Customer Relationship Management, Sports Marketing and Luxury Marketing. - Dipl.-Oek. Astrid Siebels – University of Hannover – Germany Astrid Siebels is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Marketing and Management at the Leibniz University of Hannover. Her research interests include Tourism Marketing, Luxury Marketing, Consumer Behaviour, Target Group "50plus" and CRM. - Prof. Priscilla Chan – The Hong Kong Polytechnic University – China Priscilla Chan (PhD), Assistant Professor II, Institute of Textiles and Clothing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Beta Gamma Sigma recipient. Her research interests include brand marketing and management, consumer psychology, cross-cultural studies, international retailing, and specialized market. - Prof. Junji Tsuchiya – Waseda University – Japan Junji Tsuchiya is full Professor and Head of Department of Sociology, Waseda University (Tokyo). His research interests include Social Theory on Collective Behavior and Social Change. - Prof. Samuel Rabino – Northeastern University – USA Samuel Rabino is a full Professor of marketing at Northeastern University College of Business, Boston, USA. His Research interests are international and fashion marketing, Product development, SMEs. - Prof. Irina I. Skorobogatykh – Plekhanov Russian Academy of Economics – Russia Irina I.Skorobogatykh (Ph.D) full professor of marketing Plekhanov Russian Academy of Economics. Editor in Chief of the Russian leading Marketing Journal "Marketing and Marketing Research" (Grebennikov Publishing house). Her Research interests include International marketing, Evolution of Marketing thoughts, Luxury Marketing. - Dr. Bart Weitz – University of Florida – USA Bart Weitz is JC Penney Eminent Scholar of Marketing and Executive Director of the David F. Miller Center for Retailing Education and Research, University of Florida. His research interests include retailing, distribution channels, sales force management, and personal selling. - Dr. Hyunjoo Oh – University of Florida – USA Hyunjoo Oh is research director of the David F. Miller Center for Retailing Education and Research, University of Florida. Her research interests include virtual shopping, visual marketing, fashion marketing, global retailing, and luxury branding. - Dr. Rahul Singh – Birla Institute of Management Technology – Greater Noida – India Rahul Singh (PhD) is Assistant Professor of Emerging Market and Finance at the Birla Institute of Management Technology, India. His research interests include Financial Risk Management, Emerging Market, and Cross Cultural Issues.

2 Abstract

The effects of country-of-origin (COO) upon consumer perceptions and purchase intentions remain of interest to marketing researchers.

Our article analyzes the perception of the COO and of brands, and their influence on consumer perception and purchasing intention. A cross-national sample was set up in order to obtain a more complex understanding of how the COO concept operates in various countries across different product categories (convenience products, shopping goods, and specialty/luxury products).

Keywords: Luxury, Country Of Origin (COO), consumer behaviour, cross-cultural analysis, international Introduction

The effects of country-of-origin (COO) upon consumer perceptions, and purchase intentions remain of interest to marketing researchers. The COO concept evolved into a more complex notion as global production operations became increasingly diverse, and new market opportunities continue to emerge in both developed and developing countries. Initially, the notion of the COO was perceived as analogous to the "made-in" country1; thus, the “country- of-manufacture” (COM)2. Put simply, the COM was the country which appeared upon the

“made-in” label. It was represented as the country where the final assembly of a product was completed, and identified as synonymous with the COO. Likewise, other concepts gradually emerged in COO literature. For instance, the Country-of-Design (COD) arose1,3 to refer to the country within which the product was designed and developed. In discussing multinational production, a clear distinction exists between COM and COD. Moreover, global companies utilize brand names to suggest a specific origin (country-of-brand – COB - effects). Finally, the COO is commonly considered as the country that consumers typically associate with a product or brand, regardless of where it was manufactured. As a result, researchers must

3 analyze the effects of interactions between the three “declinations” of origin: COO in the broad sense, the COD, and the COM.

Despite the various theoretical contributions, a common thread may be found between the

COO, COD, and the COM. The COO impacts consumer perceptions, and behaviours through the image of the product’s country-of-origin. The image is the representation, reputation, or the stereotype of a specific country which consumers associate with the products4,5.

Furthermore, according to Roth and Romeo6, a country's image arises from a series of dimensions that qualify a nation in terms of its production profile. Such dimensions include the following aspects: innovative approach (superior, cutting-edge, technology); design

(style, elegance, balance), prestige (exclusiveness, status of the national brands); and workmanship (reliability, durability, quality of national manufactures). Usunier7,8 provides a more comprehensive definition of an image is a multidimensional construct influenced by cognitive components, affective components, and stereotypes. Given the strong associations between the country image and product quality in relation to product/brand evaluations9, it becomes necessary to distinguish how global consumers perceive the redefined concept of country-of-origin. They perceive the COO as the country of product design, and as the country of product assembly/manufacture. The use of varying products in different countries, moreover, has caused contradictory findings in previous studies of the effect of the COO upon consumer perceptions and purchase behaviors.

Hence, our research aims to examine the perception of the COO and of brands (taken both in the general sense and also with specific reference to the world of luxury) and their influence on consumer behaviour. A cross-national sample was set up in order to obtain a more complex understanding of how the COO concept operates in various countries across different product categories (convenience products, shopping goods, and specialty/luxury products). We defined the following research questions:

4 . Q1 – What are the cross-cultural perceptions of the COO concept (construct, relevance)?

. Q2 – What are the cross-cultural perceptions upon the country image among a group of

Nations (Italy, France, Germany, Russia, India, China, Japan, USA)?

. Q3 – What are the cross-cultural perceptions of the brand concept (construct, relevance)?

. Q4 – Do COO and Brand influence the perceptions and purchasing intentions for

convenience, shopping and specialty (luxury) goods?

. Q5 – Is there a COO, and Brand interaction effect on consumer behaviour?

A network of international scholars from Italy, France, Germany, Russia, India, China,

Japan and the United States, was assembled to address these matters. Therefore, this paper puts forth the final qualitative results and exploration of our research.

1 Literature Review

1.1 Brand impact on perceptions and purchasing intentions The brand plays an integral role in constructing the COO image of a product. Likewise, a brand may influence customers' perceptions and attitudes in several ways. The dominate components of the brand influence upon customers’ purchasing intentions may be analysed through the investigation of three key issues. Namely: - the basic components, and specific functions the brand performs; - the concept of brand personality and the brand’s relational dimension; - and finally, the notion of brand experience.

1.1.1 The basic components and specific functions performed by the brand It is commonly accepted that the brand usually represents “the memory” of a firm, which encompasses all of the investments, research activities, and process technologies or innovations the firm carries out over time. As such, a brand effectively embodies the firm’s history10,11. Nevertheless, customers may utilize brands as a vehicle or mode of expression of attitudes, individualism, and needs12. According to Zara13, the brand is structured upon the basis of three fundamental components: firstly, the identity component (signs of recognition);

5 secondly, the perceptual component (cognitive associations and perceptions)14; and lastly, the trust component (confirmation of expectations).

The examination of specific functions the brand performs further illuminates the analysis of brand influence over consumers' perceptions, and purchasing decisions. Kapferer and

Thoenig15, in addition to Lambin16, classify a series of utility functions that can be attributed to the brand. These functions can be useful for both customers (orientation, guarantee, personalisation, practicality, lucid functions), and for manufacturers (protection, positioning, capitalisation).

Furthermore, there exists a contemporary trend amongst consumers who research emotional elements, which reinforce the brands' strategic dimension17,18. In discussing the strategic dimension, we must consider its impact upon consumers' perceptions, and purchasing intentions. The consumers' research of emotional elements, which are sometimes anchored into socio-cultural trends toward which customers feel a sense of belonging19,20.

They research emotional elements when they are tangible, and objective elements play a secondary role. Therefore, firms attempt to create a “symbolic” universe surrounding their products as a way to reinforce consumers' brand loyalty21.

1.1.2 Brand personality and brand relational dimension An in-depth exploration of the brand relational characters must begin with the comprehension of “brand personality.” Cook22 believes that the relationship between the brand and the consumer reflects several features similar to an affective relation between individuals. He also suggests that a veritable personality can be ascribed to the brand. Years later, Aaker23, in her seminal work, defines brand personality as “the set of human characteristics associated with a brand.” She also built the first scale to measure brand personality. Firms increasingly attempt to personify their brands with the purpose of enabling consumers to reflect their personality through brand choice. In addition, Grandi24 emphasizes that a consumer’s perception of a brand is that of a personified image, built up in a symbolic

6 manner partly through the virtue of the communicative effort firms undertake. Likewise, it is argued that what the consumer desires, and actually purchases, transpires as the global personality of the product. Its global personality consists not only of physical components, but also consists of the perception built up in the minds of consumers, and therefore, the public25.

For Blackstone26,27, the interplay between a brand and the consumer, concerns a wealth of dimensions, which all surpass the brand image or personality. In adopting this approach, it becomes crucial to gather information about not only the consumer's brand perception, but also the consumers' ideas concerning how the brand perceives its customers. In addition to

Blackstone's contribution, Manaresi28 then develops the theory of relational bases. Though it was founded upon the metaphor of an interpersonal relationship between the consumer and the brand, relational bases endeavour to integrate the measurement of rational and emotive aspects, in addition to the extent through which the brand attempts personalisation.

Considerable empirical evidence supports the above interpretation of the brand personality28,29. The customer shows a tendency to anthropomorphise products and brands, even considering personifying brands -- thus, endowing them with typically human personality traits and characteristics30.

1.1.3 The brand experience as a relational frontier The relational frontier broadens the brand symbolic implications toward the frontier of experiential branding. The rational frontier becomes the area where experience assumes the role of a new tool for value creation31. The brand then acts as the container which gathers assorted strands of experience. In branding strategies, experience derived from product use is supplemented through the overall experiential knowledge of the brand (brand experience). It aims to reinforce the link between the brand and the customer. This perspective fosters a radical influence upon brand identity characters, thereby transforming brands into suppliers of experience32,33. The brand, therefore, takes on a differentiating role, which impacts

7 consumers' preferences, as well as the likelihood that customers will repeat the purchasing act over time. Finally, the brand extends its capacity to influence perceptions, and purchasing intentions through its capacity to activate a relational, and experiential interaction.

1.2 COO and Brand interaction effect on consumer behaviour Several researchers have analysed the interactions between the brand, and the country of origin (COO) in addition to each one's effect upon individuals’ perceptions, and purchasing intentions.

Haubl and Helrod34 noted that the qualitative perception of a product becomes more positive when the unity between the brand and the country of production is recognised. A study carried out by Busacca, Bertoli and Molteni35, stresses that the effect of the interaction between the images of the brand and country of origin varies in direction and intensity. Its collaborative interaction depends upon the perceptual consonance of these two aspects36,37.

Therefore, the perceived place of origin is not only a demographic variable. The perceived place of origin contributes to shaping of the brand personality38. As a result, it becomes necessary to illustrate the accord between the brand, and its country of origin.

Analysis of the COO, and brand interactions are especially important for global brands, which are represented by products with different COD and COM. According to Pecotich and

Ward39, when customers become familiarized with a brand, the brand itself gradually acquires a holistic image which incorporates a sum of different elements. Moreover, customers that are familiar with a brand tend to pay decreased attention to specific information concerning the brand -- explicitly the price, or the COO. Other empirical studies40 reveal that the COO boasts of higher importance than the brand itself in field of perception, and of product quality evaluations. Conversely, when customers move from perceptions to purchasing intentions, the roles are reversed, with the brand exerting greater influence than the COO41.

8 2 Methodology In order to test the research questions, a statistically non-representative sample of 165 undergraduate management students taken from the universities participating in the survey was composed. The characteristics of the sample are shown below in Table 1. The sample size was considered appropriate given that we were more interested in the chief psychological processes, versus the generalisation of our results42,43. Regarding the utilisation of students as survey groups, it should be noted that this choice is prevalent in social science research, which is designed to analyse perception and levels of familiarity/renown of brands (with particular reference to the world of luxury). Peterson44 offers two central reasons to explain the validity of samples composed by management students in multi-country research. On the one hand, student samples are relatively homogeneous in terms of demographics, socioeconomic background, and education. Conversely, the use of management students limits the potential problems that usually arise in a multi-language context, since management students often have a strong grasp of English (which was used as the common language in our research).

Table 1 – Characteristics of the sample

Age Research Respondents Male Female (average) Group n. n. n. Italy 17 9 8 23.6 France 20 8 12 22.8 Germany 15 7 8 24.5 Russia 23 7 16 25.8 India 23 11 12 24.6 China HK 10 6 4 23.6 Japan 18 9 9 25.7 USA* 39 14 25 26.8 Total 165 71 94 * USA research group is composed by 2 different Universities

9 The empirical survey was planned and conducted as follows:

A) Constitution of a non-representative sample with the following characteristics: age range:

20-28; at least 10 respondents for each research group; both male and female; living

within the borders of each geographic group.

B) Design of a semi-structured interview guide, based upon the theoretical works previously

analysed, and developed by the members of the international network involved in the

research.

C) Field survey: the students were divided into eight geographic research groups; in each

group the local researchers interviewed the sample groups using the semi-structured

guide (interview length range: 45 minutes – 1 hour); an overall total of 165 respondents

were obtained. Deliberately, we did not seek to form a representative sample of brands

from different categories of luxury goods. The luxury brands were selected by

respondents as being the most representative of the luxury sector. The sample of brands

is very homogeneous in terms of business sector so that we can isolate the effect of COO

without the influence of product category.

D) Data processing and standardisation of the output format.

The guide format used (semi-structured) proposed both opened, and closed questions; our objective was to conduct a deep analysis of COO and Brand influence in perceptions and purchasing intentions and this methodology allows a wider exploration than a quantitative process.

3 General results: The cross-cultural perception of the COO and the brand concept as well as their influence on young people’s consumer behaviour. In this part of our paper, an aggregate analysis of young people’s perceptions of the COO and brand concept as well as their influence on the consumer’s purchasing intention is performed, in order to offer a preliminary answer to the research questions.

10 Empirical findings related to Q1: The cross-cultural perception of the COO concept

Based on the theoretical contributions considered, the researchers asked young people to assess the importance of COD and COM as constituent parts of a product’s COO. As shown in Table 2, according to the majority of respondents, the perception of a product’s COO depends on both the country where it was designed and the country in which it was physically produced and/or assembled. Thus, the attribution “made in xy” is accepted only if the product has the same COD and COM. However, from a cross-cultural point of view the interpretation differs significantly between the nations considered; 71.87% of young Germans consider the

COO to be the result of COM/A, whereas 63.61% of young Japanese consider the COD to be more important, as do the young Italians; the other countries consider the COO to be the joint result of COD and COM both being of approximately equally importance.

Table 2: The COO concept according to the young people surveyed Research Group COD COM/A Total COO Italy 60.59 39.41 100.00 France 51.75 48.25 100.00 Germany 28.13 71.87 100.00 Russia 52.83 47.17 100.00 India 53.57 46.43 100.00 Japan 63.61 36.39 100.00 Usa – Mass 58.81 41.19 100.00 Usa – Florida 48.95 51.05 100.00 China – HK 46.00 54.00 100.00 Total 51.58 48.42 100.00 In other words: For the majority of our respondents, COO is linked to the country both of design and of physical manufacture, only the balancing differs – this is most evident when we compare the Germans and the Japanese who perceive the concept of COO to be explained largely by the COD (Japanese) or COM (Germany).

Concerning the statistical significance within the COD/COM (table 2), we first conducted a test by comparing the results of each country with a standard 50/50. Due to the size of our sample, only the answers for three countries (Italy |Zc| = 3.396, Japan |Zc| = 3.129 and

Germany |Zc| = 2.870) were really significant (P <.05).

11 We then tried to compare the countries with each other by conducting a test of one-way

Anova. This test allowed us to highlight potential differences between countries (F = 3.65 for

the COD and 3.59 for COM / A; with P <.05). A test for comparing mean values two by two

(Duncan) shows that Japan and Germany seem to be different from each other (the difference

is averaging 40.28 with a standard deviation of 8.61).

Empirical findings related to Q2: The cross-cultural perception of the country’s image

among a group of Nations

With reference to the model proposed by Roth and Romeo6, the researchers asked the

young people interviewed to assess the key image characteristics of a set of countries (Italy,

France, Germany, Russia, China, Japan, USA) using a five-point Likert scale (see Table 3);

the evaluation criteria included the country’s innovativeness, design, prestige, and

workmanship.

Table 3: Country ratings and mean values with regard to innovativeness, design, prestige, and workmanship Key country image Italy France Germany Russia China Japan USA characteristics Innovativeness The inclusion of new 3.16 3.23 3.80 2.34 3.16 4.49 4.13 technology and engineering advances in a product. Design The appearance, style, 4.56 4.24 3.32 2.35 2.33 3.72 3.60 color(s), elegance and variety. Prestige The exclusivity, status, and 4.42 4.37 3.65 2.36 2.04 3.60 3.73 brand name reputation. Workmanship The product's reliability, 3.76 3.64 4.16 2.50 2.57 4.23 3.65 durability, craftsmanship, and manufacturing quality. Five point scale: 1= not associated at all; 2=not associated; 3=neutral; 4=associated; 5=strongly associated The results reveal a number of considerations that can be summarized in three main

themes: I) Each country is qualified by an image rooted in one or two most applicable factors;

thus, Japan (4.49), USA (4.13), and China (3.16) are – compared to the other qualities –

mainly characterized by “Innovativeness”, Italy by “Design” (4.56), Germany (4.16) and

Russia (2.50) by “Workmanship”, and France by “Prestige” (4.37). II) Generally speaking,

12 the key factor that qualifies the image of each country reaches one of the highest ratings in that specific characteristic compared to others. In particular, Japan reaches the highest rating of all countries for “Innovativeness” (4.49) and “Workmanship” (4.23), Italy for “Design”

(4.56) and “Prestige” (4.42). III) Even if the country images are rooted in a specific factor, they are affected additionally by the other key characteristics. However, in the set of countries considered, the images of Russia and China represent the lowest values for all qualities; for “Prestige”, China shows the lowest rating of all (2.04), whereas the highest value of all is Italy’s “Design”-rating.

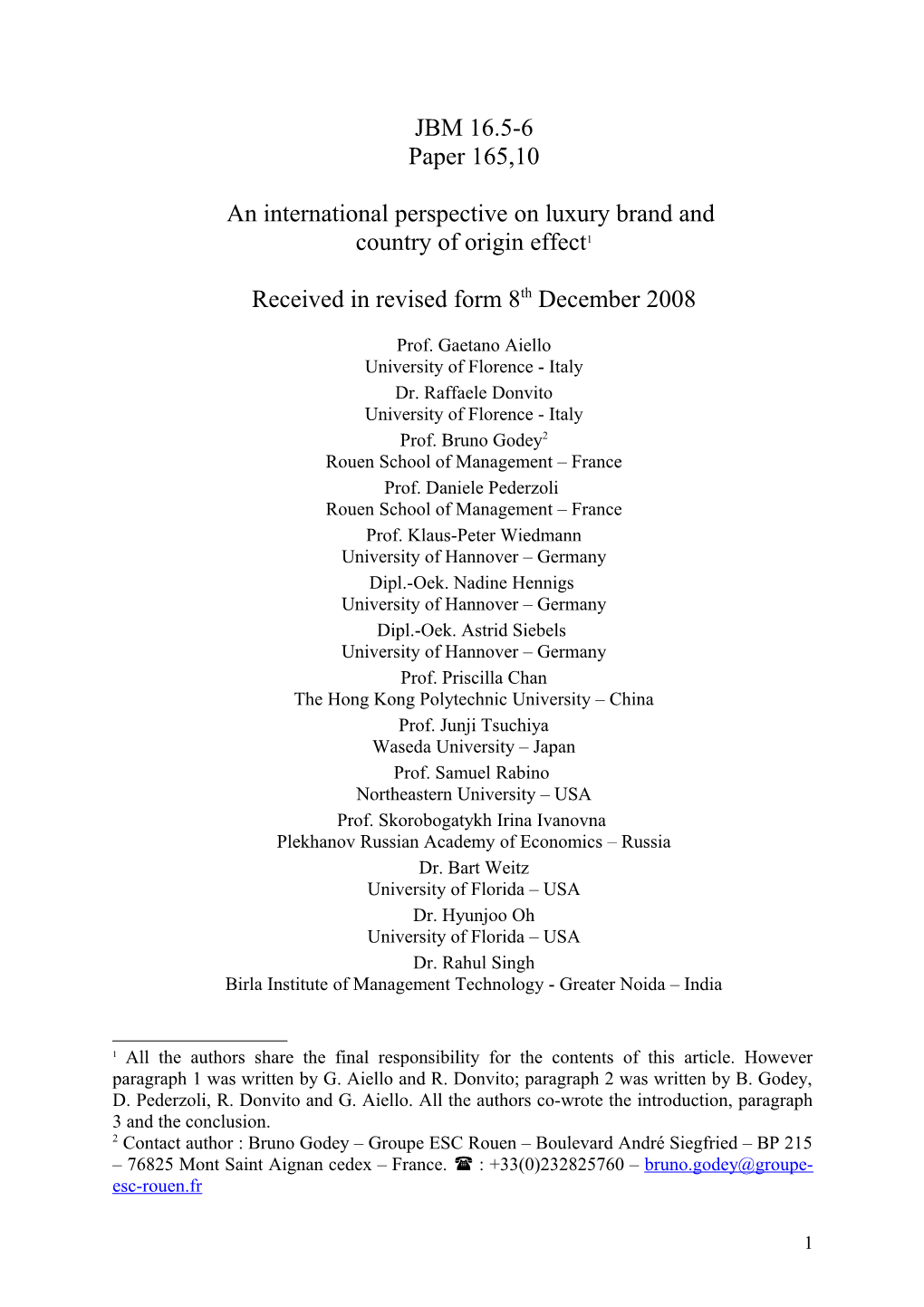

Figure 1: Statistical significance tests: innovativeness, design, prestige, and workmanship

4.56 ItalyItaly 4.42 ItalyItaly 4.49 Japan Japan 4.37 FranceFrance 4.24 FranceFrance 4.13 USAUSA 4.23 JapanJapan 4.16 GermanyGermany 3.73 3.80 GermanyGermany USAUSA 3.76 ItalyItaly 3.72 Japan Japan 3.65 GermanyGermany 3.65 USAUSA 3.60 USAUSA 3.60 JapanJapan 3.64 FranceFrance 3.32 GermanyGermany 3.23 FranceFrance 3.16 ItalyItaly 3.16 ChinaChina 2.57 ChinaChina 2.50 RussiaRussia 2.36 RussiaRussia 2.35 RussiaRussia 2.34 RussiaRussia 2.33 ChinaChina 2.04 ChinaChina

Innovativeness Design Prestige Workmanship

Regarding the statistical significance of the results, we performed tests to compare the mean values with apparied samples. These tests have allowed for each dimension to generate on the one hand significant differences between countries and on the other hand some groups of countries (shown above).

13 Empirical findings related to Q3: The cross-cultural perception of the brand concept

As regards the exploration of the concept of a brand widespread among young people, a multiple choice questionnaire design based on the theoretical contribution previously mentioned was set up by the researchers. The results as shown in Figure 2 reveal that the brand is mainly considered as a sign of identification (4.59) and also, for most of the respondents, as a set of cognitive and perceptive associations (4.06); on the contrary, a brand is not fully perceived as a basis of trust (3.98) or someone to relate to (3.54).

Figure 2: The brand concept according to the respondents

A brand is:

5,00 4,59 4,50 4,06 3,98 4,00 3,54 3,50

3,00

2,50

2,00

1,50

1,00 Sign of identification Set of cognitive and Trust "container" Someone to relate to perceptive associations

Five point scale: 1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=neutral; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree The questionnaire also provided an open answer asking the young people to write down their own personal definition of brand. The answers given by the respondents were all directly related to the meanings proposed in the closed list by the researchers3.

In order to define the issue of a brand influence in a general framework, the research has examined the specific functions performed by the brand itself in the opinion of the interviewee. As shown in Figure 3, the functions of guarantee (4.30) and orientation (3.90) are those which predominantly qualify the role of a brand in the buyers’ perception. The personality and handiness function show similar average ratings (3.72; 3.71), whereas the 3 The qualitative analysis of this open answer is not included here because the authors believe that it would not have added any specific value to the paper.

14 recreational function of a brand is perceived to be less important (3.09). Besides, the research, within the limits of its representativeness, did not find significant evidence of the relational and experiential brand perspective. However, it is believed that the type of survey instrument used in this research was not the most appropriate for analyzing the relational and experiential perspective linked to the brand.

Figure 3: Brand functions according to the respondents

Brand functions

4,50 4,30

4,00 3,90 3,72 3,71

3,50 3,09 3,00

2,50

2,00

1,50

1,00 Orientation Guarantee Personality Handiness Recreational

Five point scale: 1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=neutral; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree Empirical findings related to Q4: The influence of the COO and the brand on product evaluation and purchase decision

In order to analyse research question Q4, the participants the study were asked how much the brand, COO, and other marketing items affect their evaluations of products and their purchase decisions. In order to gain potential insight into differences between luxury goods and other product categories, we used the three categories, convenience goods, shopping goods, and specialty-luxury goods4. The results are shown in Table 4 a-b.

4 Traditionally (Copeland 1923) Convenience goods are those that the customer purchases frequently, immediately, and with minimum effort (e.g. soaps, newspapers, milk). Shopping goods are those which usually requires a more involved selection process than convenience goods. A consumer usually compares a variety of attributes, including suitability, quality, price, and style (furniture, electronics, inexpensive clothing). Specialty- Luxury goods have particularly unique characteristics for which a significant group of buyers is willing to make a special purchasing effort (luxury cars, professional photographic equipment, high-fashion clothing).

15 Table 4a: Items affecting the evaluation of the Table 4b: Items affecting the product purchasing decision Product evaluation Purchasing decision Items Convenience Specialty -Luxury Convenience Specialty Shopping goods Shopping goods goods goods goods Luxury goods Brand 2.68 3.87 4.69 2.63 3.68 4.44 COO 2.60 3.26 3.87 2.27 2.84 3.40 COD 2.22 3.16 3.93 2.06 2.85 3.51 COM/A 2.70 3.31 3.64 2.48 2.91 3.34 Price 4.09 4.14 3.53 3.94 4.11 3.94 Warranty 2.70 3.63 4.04 2.50 3.34 3.74 Design 2.66 4.08 4.68 2.51 4.10 4.61 Advertising and communication 2.98 3.31 3.42 2.50 3.07 3,29 Five point scale: 1= no impact at all; 2= little impact; 3=neutral; 4= medium impact; 5=strong impact With regard to the evaluation of the different factors affecting the product categories and purchasing decisions the results show: a) The most important factors affecting the evaluation of luxury goods are the “brand”

(4.69) and the “design” (4.68). With regard to shopping goods, the “brand” only has a

medium impact (3.87) on the evaluation and for convenience goods the brand plays an

inferior role (2.68). The most important factor for these two categories is the “price”

(shopping goods 4.14/convenience goods 4.09). For convenience goods, the” price” is

even by far the most important factor whereas all the other factors are rated rather

insignificantly for the product evaluation. b) The brand affects the evaluations of all the product categories more than the COO. c) The COO effect only has a medium impact (3.87) on the evaluation of luxury goods,

coming at fifth place. For shopping goods the COO is not of high importance (3.26) and it

is rather unimportant for convenience goods (2.60). d) In general, the highest scores for all the items were in luxury goods, with only one

exception which is the price. Here, the results are reversed, indicating that, where luxury

goods are concerned, the price is less important than the other aspects.

16 e) All the results described above in a) – d) are similar for purchase decisions (Table 4b),

however, with a slightly decrease in the absolute scoring rates. Nevertheless, the relative

evaluations are very similar. f) With regard to statistical significance tests, we performed tests comparing mean values

two by two for each category of products. These tests have allowed us first to verify that

the structure of items in the “product evaluation” was very similar to that for the

“purchasing decision” for the three categories of products. For “convenience goods”, the

item “price” is significantly different from a group formed by the other variables. For

“shopping goods”, “price” and “design” form a clearly distinct group from other

variables. For luxury goods, “design” and “brand” are significantly detached from other

variables.

Empirical findings related to Q5: The COO and brand interaction effect on consumer behaviour

In the first step, the participants were asked to name the country of origin for each luxury brand listed in Table 5. These brands were selected in accordance with the results of a previous cross-cultural study conducted by the authors of this paper45. Table 5 shows the results in terms of the percentage of correct answers given by the participants. The luxury brands were correctly matched to their “historical” country of origin by over 75% of the respondents (except for Burberry); for seven brands in the list this proportion reaches more than 90%. Therefore, the national component appears to be a characteristic of the luxury brand strongly recognized by the interviewed.

17 Table 5: The Country of Origin association of luxury brands N. Brand Country of Origin associated Percent of correct association 1 Cartier France 98.1% 2 Chanel France 98.1% 3 Dolce e Gabbana Italy 96.2% 4 Armani Italy 94.3% 5 Gucci Italy 94.3% 6 Versace Italy 94.3% 7 Yves Saint Laurent France 90.6% 8 Dior France 88.7% 9 Valentino Italy 88.7% 10 Louis Vuitton France 86.8% 11 Prada Italy 84.9% 12 Bulgari Italy 83.0% 13 Hermes France 81.1% 14 Salvatore Ferragamo Italy 75.5% 15 Burberry UK 60.4% In the second step, the interviewers asked the participants to assess the relevance (from 0%

to 100%) of the brand and COO for their own luxury product evaluation and purchase

decision with specific reference to the selected luxury brands: “Do you buy because of the

“made in” country or because of the brand?” Table 6a emphasizes the special importance of

the brand in comparison to the COO for both the product evaluation and the purchase

decision. Taking a closer look at the COO concept and the differentiation between COD and

COM, the COD seems to have a slightly higher influence than the COM (Table 6b).

Table 6.a: The relevance (from 0% to 100%) of brand and COO in Table 6.b: Within the COO (considered luxury product evaluation and purchase decision (Do you buy because equivalent to 100) which kind of COO is of the “made in” or because of the brand?) relevant (from 0% to 100%) Brand name Brand COO COD COM Chanel 77.58 27.70 59.11 38.80 Gucci 73.22 27.21 58.69 39.15 Louis Vuitton 72.69 26.65 58.17 41.07 Armani 71.89 28.35 57.39 40.83 Prada 71.45 27.87 58.33 40.15 Cartier 71.01 28.39 57.25 40.99 Dolce e Gabbana 70.74 28.90 59.39 37.48 Dior 70.73 28.71 57.79 39.81 Burberry 70.31 29.07 57.71 40.30 Versace 70.10 29.9 59.77 38.08 Hermes 69.41 30.28 56.06 41.45 Bulgari 69.07 30.13 55.19 43.26 Yves Saint Laurent 68.41 31.28 56.37 40.32 Salvatore Ferragamo 68.24 31.12 56.82 41.63 Valentino 67.95 31.43 58.09 40.00 A cross-analysis of Table 5 and 6a leads to some exploratory considerations about the

interaction between brand and COO within the luxury market: Although the differences

18 between the ratings assigned to the various brands are not very marked, nevertheless, it is possible to identify four types of cases as shown in Figure 4. In particular, taking into account the relationship between “the importance of the luxury brand in product purchase decision” and the “brand COO identifiability”, it seems that:

1) When both the importance of the luxury brand for the product purchase decision and the

brand COO identifiability are high, the product is mainly purchased because of the brand

itself and its clear national origin.

2) When the importance of the brand for the luxury product purchase decision is high and

the brand COO identifiability is low, the product is purchased mainly because of the

brand.

3) When the importance of the luxury brand for the product purchase decision is low and the

brand COO identifiability is high, the product is purchased for the national component

that incorporates the brand.

4) When both the importance of the luxury brand for the product purchase decision and the

brand COO identifiability are low, the product is purchased because of a combination of

multiple factors.

19 Figure 4: Interaction between COO and Brand for Luxury products

ChanelChanel The product is purchased mainly because of The product is mainly purchased because of the brand the brand itself and its clear national origin High BurberryBurberry Importance of Armani the luxury Armani brand in FerragamFerragam product oo purchase decision The product is purchased because of a The product is purchased for the national Low combination of multiple factors component that incorporates the Brand

Low High Brand COO identifiability Range of current research empirical findings

Conclusion In our research, 165 people were interviewed in 8 different countries. We observe strong differences between countries concerning the concept of COO. The images of countries analyzed are clear, well defined and differentiated. The vision of brand is very traditional (e.g. “sign of identification”, “guarantee” and “orientation”). In addition, for all categories analyzed, brand has a higher influence on product evaluation and purchase decision than COO. For luxury goods, brand is much more relevant than COO in evaluation and purchasing decision. The luxury brands are generally well-known to respondents and their nationalities are clear. Young people seem clearly more interested in brands, and in the projection of the nationality of these brands, than in COO. Therefore, we will have to develop a causal model for evaluating the respective weight of the brand and COO. The main limit of our research is the size and the composition of the sample, as already explained in the methodology paragraph. However, some interesting results emerge from our research, especially concerning the possibility to identify potential country groupings based on the analysis variables. This would be worth confirming by a cluster analysis based on a larger sample The respondents seem to have fully grasped the globalization of markets and especially of the value chain, from conception and design to the manufacture of a product. Some interesting cross-cultural differences among respondents emerge for this analysis too.

20 Nevertheless, some cross-cultural differences appeared in the COO concept, so it would be interesting to investigate whether these differences emerge also in a trans-national quantitative research. Based on our results to date we can imagine several future avenues of research which could be of interest both to researchers in the area of luxury brands and to others in the area of perception of COO in a multicultural context.

21 References

22 1 () Nebenzahl, I.D., Jaffe, E.D., Lampert, S.I., (1997), ‘Towards a theory of country image effect on product evaluation’, Management International Review, Vol. 37, pp. 27–49. 2 () Samiee, S. (1994), ‘Customer evaluation of products in a global market’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 25, N° 3, pp.579–604. 3 () Jaffe E. D., Nebenzahl I.D., (2001), ‘National image and competitive advantage: The theory and practice of country-of-origin effects’, Copenhagen Business School Press, Copenhagen. 4 () Nagashima A., (1970), ‘A comparison of Japanese and US attitudes toward foreign products’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 34, N° 1, pp.68–74. 5 () Nagashima A., (1977), ‘A comparative ‘made-in’ product image survey among Japanese businessmen’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 41, N°. 3, pp. 95–100. 6 () Roth M.S., Romeo G.B. (1992), ‘Matching product category and Country Image Perceptions: A framework for managing Country of Origin Effects’, Journal of International Business Studies, Winter, Vol. 23, N° 3, pp. 477-497. 7 () Usunier J.C. (1993), ‘Marketing across Cultures’, Hemel Hempstead, Prentice Hall. 8 () Usunier J.C., Lee J.A. (2005), ‘Marketing across Cultures’, 4th ed., Pearson Educational. 9 () Kotler, P., Gertner, D. (2002), ‘Country as brand, product and, beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective’, Journal of Brand Management, Vol. 9, N° 4, pp. 249-261. 10() Deichmann M., (1991), ‘Introduzione all’edizione italiana’, in Kapferer J.N., Thoenig J.C. (eds.), ‘La marca. Motore della competitività delle imprese e della crescita dell’economia’, Guerini e Associati, Milano. 11() Collesei U., (2000), ‘Marketing’, Cedam, Padova. 12() Keegan W., Moriarty S., Duncan T., (1992), ‘Marketing’, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall. 13() Zara C., (1997), ‘La valutazione della marca: il contributo del brand alla creazione del valore d’impresa’, ETAS, Milano. 14() Peter, P. and Olson, J. (1987), ‘Consumer Behaviour. Marketing Strategy Perspectives’, Richard Irwin, Inc. 15() Kapferer J.N., Thoenig J.C., (1991), ‘La marca. Motore della competitività delle imprese e della crescita dell’economia’, Guerini e Associati, Milano. 16() Lambin J.J. (1991), ‘Marketing’, McGraw-Hill, 1st ed., Milano. 17() Aaker D. A., (1997), ‘Brand equity: la gestione del valore della marca’, Franco Angeli, Milano. 18() Aaker D. A., Joachimsthaler E., (2003), ‘Brand leadership’, Franco Angeli, Milano. 19() Fabris G., (1999), ‘Verso nuovi modelli di consumo’, in Varaldo R. (ed.), ‘Il marketing negli anni Duemila. Sfide per il nuovo secolo’, Guerini e associati, Milano. 20() Fornari D., (1995) ‘Le nuove dimensioni dei modelli di consumo in Italia’, in ‘Trade Marketing’, N°. 15, pp. 3-36. 21() Marzili, P.G., (1979), ‘Nuovi orientamenti della funzione di marketing’, Tipografia Capponi, Firenze. 22() Cook W.A. (1992), ‘Brand Equity as a Love story’, Journal of Advertising Research, November-December, Vol. 32, N° 6, pp.7-8. 23() Aaker J.L. (1997) ‘Dimensions of brand personality’, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. XXXIV, N° 3, pp. 347-356. 24() Grandi R. (1987), ‘Come parla la pubblicità – Modelli comunicativi degli Spot pubblicitari’, Edizioni Sole 24 ore, Milano. 25() Dogana F. (1976), ‘Psicopatologia dei consumi quotidiani’, Franco Angeli, Milano. 26() Blackston M. (1992), ‘Observations: Building Brand Equity by Managing the Brand’s Relationships’, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 32, N° 3, pp.79-83. 27() Blackstone M. (1993), ‘Beyond Brand Personality: Building Brand Relationships’, in D.A. Aaker, A.L. Biel (eds.), ‘Brand Equity and Advertising: Advertising’s Role in Building Strong Brands’, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. 28() Manaresi A., (1999), ‘La competizione tra distributori per la relazione con il cliente: dalla gestione di relazioni al recupero del paradigma transazionale’, in ‘Trade Marketing’, N°. 26, pp. 97-118. 29() Gurviez P. (1996), ‘The trust Concept in the Brand-Consumers Relationship’, in Proceeding EMAC, Budapest, pp. 559-574. 30() Codeluppi (1992), ‘I consumatori. Storia, tendenze, modelli’, Franco Angeli, Milano. 31() Pine B.J. II, Gilmore J.H., (1999), ‘The Experience Economy. Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage’, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts. 32() Schmitt B., (1999a), ‘Experiential marketing’, in ‘Journal of Marketing Management’, Vol. 1-3, N°. 15, pp. 53-67. 33() Schmitt B., (1999b), ‘Experiential marketing’, The Free Press, New York. 34() Haubl G., Elrod T. (1999), ‘The impact of congruity between brand name and country of production on consumers’ product quality judgements’, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 16, N° 3, pp. 199-215. 35() Busacca B., Bertoli G., Molteni L. (2006), ‘Consumatore, marca ed ‘effetto made in’: evidenze dall’Italia e dagli Stati Uniti’, Finanza marketing e produzione, Vol. 24, N°. 2, pp. 5-32. 36() Biel, A.L. (1993), ‘Converting image into equity’, in Aaker, D.A. and Biel, A.L. (eds.), ‘Brand Equity and Advertising: Advertising's Role in Building Strong Brands’, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. 37() Busacca B. (2000), ‘Il valore della marca: fra postfordismo ed economia digitale’, Egea, Milano. 38() Thakor M.V., Kohli C.S. (1996), ‘Brand origin: conceptualisation and review’, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 13, N°. 3, summer, pp. 27-43. 39() Pecotich A., Ward S. (2007), ‘Global branding, country of origin and expertise. An experimental evaluation’, International Marketing Review, Vol. 24, N° 3, pp. 271-296. 40() Ahmed Z.U., Johnson J.P., Ling C.P., Fang T.W., Hui A.K (2002), ‘Country-of-origin and brand effects on consumers’ evaluations of cruise lines’, International Marketing Review, Vol. 19, No. 2/3, pp. 279-302. 41() d’Astous A., Ahmed S.A., (1999), ‘The importance of country images in the formation of consumer product perceptions’, International marketing review, Vol. 16, N°. 2, pp. 108-125. 42() Grewal R., Mehta R., Kardes F. (2000), ‘The role of the social-identity function of attitudes in consumer innovativeness and opinion leadership’, Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 21, N° 3, pp.233-252. 43() O’Cass A. (2000), ‘An assessment of consumers’ product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing’, Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 21, N° 5, pp.545-576. 44() Peterson R.A. (2001), ‘On the Use of College Students in Social Science Research: Insights from a Second-Order Meta-Analysis’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 28, N° 3, pp.450-461. 45() Aiello G., Donvito R., Godey B., Pederzoli D., Wiedmann K-P., Hennigs N., Siebels A. (2007), ‘Young people’s perception of luxury concept: An international comparative analysis’, 6th International Italy-France Congress – Marketing Trends, 26th-27th January, Paris.