Actors and Acting During Shakespeare’s Time Adapted from Shakespeare by Christopher Martin (Vero Beach, Florida: Rourke Enterprise, 1988), pp. 41-72 (pink)

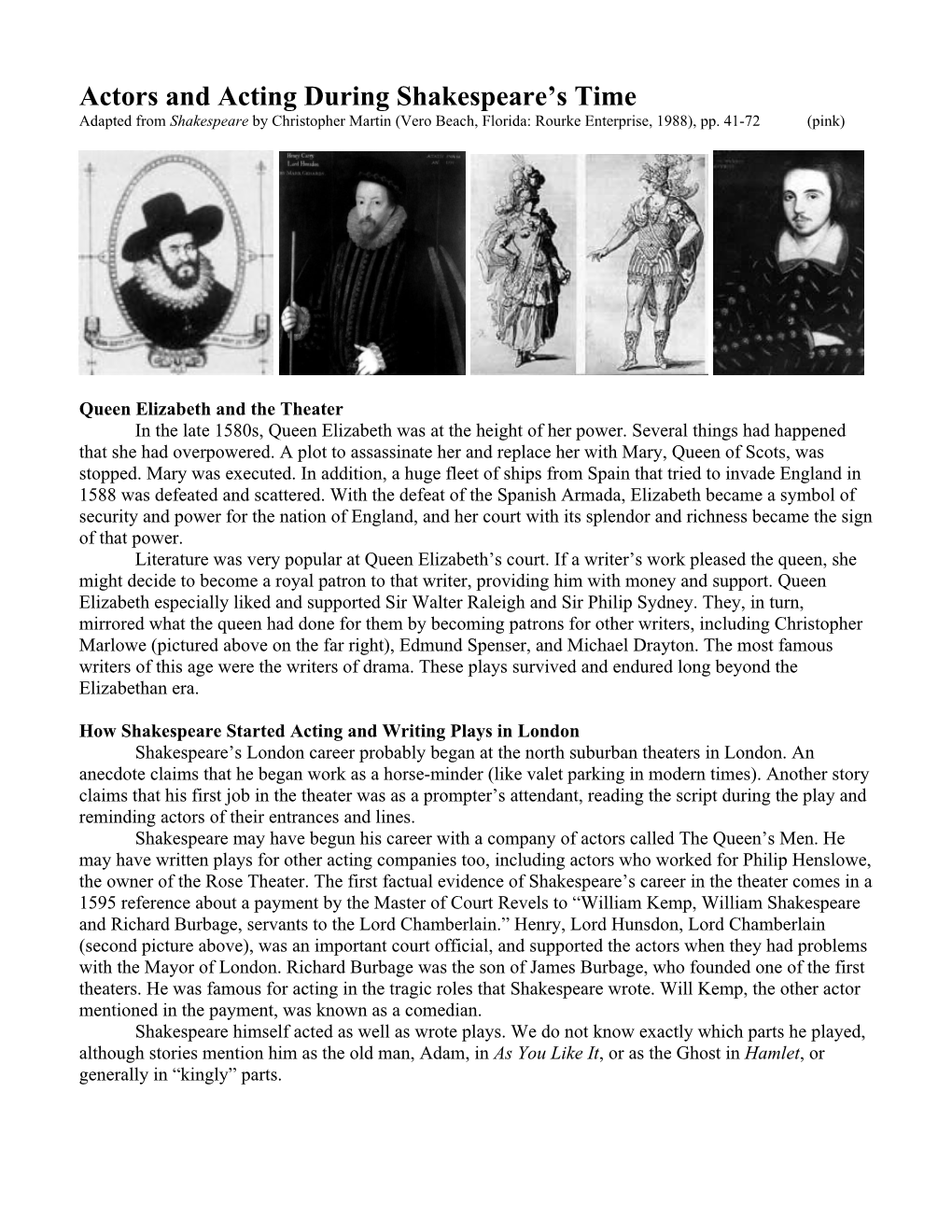

Queen Elizabeth and the Theater In the late 1580s, Queen Elizabeth was at the height of her power. Several things had happened that she had overpowered. A plot to assassinate her and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots, was stopped. Mary was executed. In addition, a huge fleet of ships from Spain that tried to invade England in 1588 was defeated and scattered. With the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Elizabeth became a symbol of security and power for the nation of England, and her court with its splendor and richness became the sign of that power. Literature was very popular at Queen Elizabeth’s court. If a writer’s work pleased the queen, she might decide to become a royal patron to that writer, providing him with money and support. Queen Elizabeth especially liked and supported Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Philip Sydney. They, in turn, mirrored what the queen had done for them by becoming patrons for other writers, including Christopher Marlowe (pictured above on the far right), Edmund Spenser, and Michael Drayton. The most famous writers of this age were the writers of drama. These plays survived and endured long beyond the Elizabethan era.

How Shakespeare Started Acting and Writing Plays in London Shakespeare’s London career probably began at the north suburban theaters in London. An anecdote claims that he began work as a horse-minder (like valet parking in modern times). Another story claims that his first job in the theater was as a prompter’s attendant, reading the script during the play and reminding actors of their entrances and lines. Shakespeare may have begun his career with a company of actors called The Queen’s Men. He may have written plays for other acting companies too, including actors who worked for Philip Henslowe, the owner of the Rose Theater. The first factual evidence of Shakespeare’s career in the theater comes in a 1595 reference about a payment by the Master of Court Revels to “William Kemp, William Shakespeare and Richard Burbage, servants to the Lord Chamberlain.” Henry, Lord Hunsdon, Lord Chamberlain (second picture above), was an important court official, and supported the actors when they had problems with the Mayor of London. Richard Burbage was the son of James Burbage, who founded one of the first theaters. He was famous for acting in the tragic roles that Shakespeare wrote. Will Kemp, the other actor mentioned in the payment, was known as a comedian. Shakespeare himself acted as well as wrote plays. We do not know exactly which parts he played, although stories mention him as the old man, Adam, in As You Like It, or as the Ghost in Hamlet, or generally in “kingly” parts. How Shakespeare Wrote Plays Shakespeare would have had little time to write. New plays were constantly required by acting companies, so he could not “lie in childbed one and thirty weeks” to produce “three bad lines.” His fellow actors tell us that he worked astonishingly swiftly and accurately: “We scarce have received from him a blot in his papers.” Shakespeare wrote 37 plays.

How Plays Were Produced When a playwright finished writing a play, it had to be licensed by the Queen’s Master of Revels to make sure it did not contain any anti-government material. The manuscript was guarded carefully by the acting company, as there were no copyright laws. A copier wrote out the actors’ parts, with prompts and cues, on six-inch wide strips of paper that could be published in very hard times for the company, or from stolen or half-remembered texts. That is why most Elizabethan plays have been lost. Playwrights sold their plays to an acting company, not benefiting from any steady success that company might have performing the play over and over. But Shakespeare made sure he was entitled to some of the profits that could be earned by an acting company performing his plays. He became a company “sharer” who was entitled to part of the profits collected at the door when people came to see the play. In this way, his wealth grew steadily, since he got money every time the play was performed by his acting company.

Costumes and Sets Although Elizabethan theater was more aural (listened to by the ear) than visual (viewed by the eye), the crowd did enjoy watching a good spectacle. Costumes for actors could be splendid to look at. In some of Philip Henslowe’s papers (he was the owner of the Rose Theater), he describes some of the costumes. He mentions “a short velvet cloak, embroidered with gold and gold spangles,” and “a crimson robe striped with gold, faced with ermine.” Even though the costumes were rich and beautiful, there was no attempt to make them historically accurate. When Roman characters performed in one of Shakespeare’s plays based on Roman history, they didn’t wear togas or other Roman costumes; they wore Elizabethan doublets and hats. In addition to costumes, some special effects and sound effects were used. Blood in fight scenes looked real because actors hid bladders of pig’s blood under their costumes. One stage direction states: “Let there be a brazen head set in the middle of the place behind the stage, out of which cast flames of fire, drums rumble within.” Another stage directions says: “Exit Venus; or if you conveniently can let a chair come down from the top of the stage and draw her up.” Sound effects were also important, from the elaborate system of trumpet calls to the rolled cannonball indicating thunder.

Boy Actors Women did not act in Elizabethan theater. It wasn’t until 1660, when King Charles II was restored to the English throne, that females were allowed to act on stage. So, acting companies relied on boys who were especially trained, and who lived in the families of the actors who trained them. They played such demanding roles in Shakespeare’s plays as “sweet” Beatrice, “heavenly” Rosalind, and charming Viola, not to mention Juliet.

Questions: 1. Name two actors who acted in Shakespeare’s plays, and what types of roles they liked to play. 2. Why were Elizabethan plays so easy to steal, and why were so many lost? 3. Name one special effect used in Elizabethan theater. 4. Who acted female roles in Elizabethan theater?