53. a Consistent Approach to the Assessment and Management of Asphyxiation Hazards K. A. Johnson View Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPA's Guidance to Protect POTW Workers from Toxic and Reactive

United States Office Of Water EPA 812-B-92-001 Environmental Protection (EN-336) NTIS No. PB92-173-236 Agency June 1992 EPA Guidance To Protect POTW Workers From Toxic And Reactive Gases And Vapors DISCLAIMER: This is a guidance document only. Compliance with these procedures cannot guarantee worker safety in all cases. Each POTW must assess whether measures more protective of worker health are necessary at each facility. Confined-spaceentry, worker right-to-know, and worker health and safety issues not directly related to toxic or reactive discharges to POTWs are beyond the scope of this guidance document and are not addressed. Additional copies of this document and other EPA documentsreferenced in this document can be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service (NTIS) at: 5285 Port Royal Rd. Springfield, VA 22161 Ph #: 703-487-4650 (NTIS charges a fee for each document.) FOREWORD In 1978, EPA promulgated the General Pretreatment Regulations [40 CFR Part 403] to control industrial discharges to POTWs that damage the collection system, interfere with treatment plant operations, limit sewage sludge disposal options, or pass through inadequately treated into receiving waters On July 24, 1990, EPA amended the General Pretreatment Regulations to respond to the findings and recommendations of the Report to Congress onthe Discharge of Hazardous Wastesto Publicly Owned Treatment Works (the “Domestic Sewage Study”), which identified ways to strengthen the control of hazardous wastes discharged to POTWs. The amendments add -

Material Safety Data Sheet Is for Carbon Dioxide Supplied in Cylinders with 33 Cubic Feet (935 Liters) Or Less Gas Capacity (DOT - 39 Cylinders)

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Prepared to U.S. OSHA, CMA, ANSI and Canadian WHMIS Standards 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY INFORMATION CHEMICAL NAME; CLASS: CARBON DIOXIDE SYNONYMS: Carbon Anhydride, Carbonic Acid Gas, Carbonic Anhydride, Carbon Dioxide USP CHEMICAL FAMILY NAME: Acid Anhydride FORMULA: CO2 Document Number: 50007 Note: This Material Safety Data Sheet is for Carbon Dioxide supplied in cylinders with 33 cubic feet (935 liters) or less gas capacity (DOT - 39 cylinders). For Carbon Dioxide in large cylinders refer to Document Number 10039. PRODUCT USE: Calibration of Monitoring and Research Equipment MANUFACTURED/SUPPLIED FOR: ADDRESS: 821 Chesapeake Drive Cambridge, MD 21613 EMERGENCY PHONE: CHEMTREC: 1-800-424-9300 BUSINESS PHONE: 1-410-228-6400 General MSDS Information 1-713/868-0440 Fax on Demand: 1-800/231-1366 CARBON DIOXIDE - CO2 MSDS EFFECTIVE DATE: AUGUST 31, 2005 PAGE 1 OF 9 2. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION EMERGENCY OVERVIEW: Carbon Dioxide is a colorless, odorless, non-flammable gas. Over-exposure to Carbon Dioxide can increase respiration and heart rate, possibly resulting in circulatory insufficiency, which may lead to coma and death. At concentrations between 2-10%, Carbon Dioxide can cause nausea, dizziness, headache, mental confusion, increased blood pressure and respiratory rate. Exposure to Carbon Dioxide can also cause asphyxiation, through displacement of oxygen. If the gas concentration reaches 10% or more, suffocation can occur within minutes. Moisture in the air could lead to the formation of carbonic acid which can be irritating to the eyes. SYMPTOMS OF OVER-EXPOSURE BY ROUTE OF EXPOSURE: The most significant routes of over-exposure for this gas are by inhalation, and contact with the cryogenic liquid. -

A Toxicological Review of the Products of Combustion

HPA-CHaPD-004 A Toxicological Review of the Products of Combustion J C Wakefield ABSTRACT The Chemical Hazards and Poisons Division (CHaPD) is frequently required to advise on the health effects arising from incidents due to fires. The purpose of this review is to consider the toxicity of combustion products. Following smoke inhalation, toxicity may result either from thermal injury, or from the toxic effects of substances present. This review considers only the latter, and not thermal injury, and aims to identify generalisations which may be made regarding the toxicity of common products present in fire smoke, with respect to the combustion conditions (temperature, oxygen availability, etc.), focusing largely on the adverse health effects to humans following acute exposure to these chemicals in smoke. The prediction of toxic combustion products is a complex area and there is the potential for generation of a huge range of pyrolysis products depending on the nature of the fire and the conditions of burning. Although each fire will have individual characteristics and will ultimately need to be considered on a case by case basis there are commonalities, particularly with regard to the most important components relating to toxicity. © Health Protection Agency Approval: February 2010 Centre for Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards Publication: February 2010 Chemical Hazards and Poisons Division £15.00 Chilton, Didcot, Oxfordshire OX11 0RQ ISBN 978-0-85951- 663-1 This report from HPA Chemical Hazards and Poisons Division reflects understanding and evaluation of the current scientific evidence as presented and referenced in this document. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Chemical Hazards and Poisons Division (CHaPD) is frequently required to advise on the health effects arising from incidents due to fires. -

Malnutrition Have Often Devel- Oped Strong Preferences for Unbalanced Diets

alnutrition can cause a specific problem or suppress a bird’s immune system, de- CHAPTER crease response to therapeutic agents, M decrease reproductive performance and prolong the period of surgical recovery. The diet of every avian patient should be carefully evaluated, even if the bird appears clinically to be well nourished. Marginal nutritional inadequacies frequently occur (see Chapter 8), and correcting the 31 diet will improve a bird’s general health and its ability to resist infectious diseases. Gastrointestinal malabsorption, hepatitis or renal disease can in- crease nutrient requirements so that diets that are sufficient in healthy birds may be insufficient for unhealthy birds. Interestingly, free-ranging gra- nivorous birds that are offered both organic (no pes- ticides) and pesticide-treated grains will preferen- ALNUTRITION tially consume the organic foods. Test birds would not M eat the pesticide-treated foods until all of the organic grains were gone. Birds with signs of malnutrition have often devel- oped strong preferences for unbalanced diets. Most seed diets, for example, contain excessive levels of fat and may be deficient in vitamins A, D3, E, B12 and K1, plus riboflavin, pantothenic acid, niacin, biotin, choline, iodine, iron, copper, manganese, selenium, Patricia Macwhirter sodium, calcium, zinc and some amino acids (eg, lysine and methionine).6 Birds can be encouraged to accept new foods by offer- ing them first thing in the morning when the appe- tite is strongest. Favorite items can be withheld until later in the day. New foods may also be mixed with the bird’s normal familiar diet. Gradually decreasing the quantity of old food items and increasing the quantity of new foods in the mixture will allow for a smooth transition in the diet. -

Uninten Onal Occupa Onal Irritant and Asphyxiant Gas Exposures

UnintenMonal OccupaMonal Irritant anD Asphyxiant Gas Exposures Margaret Cook-Shimanek, MD, MPH1, Sahaphume Srisuma, MD2,3, and Christopher Hoyte, MD1,2 1University of Colorado, Denver, CO 2Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center, Denver Health and Hospital Authority, Denver, Colorado 3Ramathibodi Poison Center, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand IntroducMon Results, conMnueD Conclusions Figure 1: Call Frequency by ReporteD Gas Exposure, 2000-2014 • Occupaonal exposures to irritant and asphyxiant • Need for addi'onal workplace controls to Carbon Monoxide Chlorine Gas Hydrogen Sulfide (Sewer Gas) Methane and Natural Gas Simple Asphyxiants hazardous gases are common. 600 prevent hazardous gas exposures 562 • Improper chemical mixing prac'ces and • Some gases are known to result in morbidity and 534 514 500 inadequate ven'laon are contribu'ng mortality, therefore characterizing these 486 460 factors to hazardous gas exposure uninten'onal exposures may direct efforts for 450 428 workplace controls. 431 432 • Most exposures resulted in mild health 400 396 383 366 effects manageable with minimal 343 343 361 Research ObjecMves 353 342 348 335 interven'on, but serious health effects can 317 319 309 300 307 occur, including death • Describe characteris'cs of occupaonal irritant 278 252 and asphyxiant gas exposures. 244 Limitaons 222 223 231 226 213 201 217 200 168 • Iden'fy gases of greatest concern to direct hazard 180 178 • No access to case notes for specific cause NUMBER OF CALLS BY GAS EXPOSURE TYPE 167 163 145 156 148 preven'on -

Hazard Classifications Used in Hazmat Table, Column 3

Hazard Classifications Used in Hazmat Table, Column 3 Class Division Name of class or division Known hazards Number Number (if any) None .............. Forbidden Material None .............. Forbidden Explosives Class 1 (Explosive) An explosive is any substance or article ‐ including a device ‐ which is designed to function by explosion (i.e. an extremely rapid release of gas and heat), or which ‐ by chemical reaction within itself ‐ is able to function in a similar manner even if not designed to function by explosion, unless the substance or article is otherwise classed. 1 1.1 Explosives (with a mass Explosives that have a mass explosion hazard. A mass explosion hazard) explosion is one which affects almost the entire load l 1 1.2 Explosives (with a projection Explosives that have a projection hazard, but not a mass hazard) explosion hazard. Explosives (with predominantly Explosives that have a fire hazard and either a minor blast 1 1.3 a fire hazard) hazard, a minor projection hazard, or both ‐ but not a mass explosion hazard. Explosives that present a minor explosion hazard. The explosive effects are largely confined to the package, and no Explosives (with no significant 1 1.4 projection of fragments of appreciable size or range is to be blast hazard) expected. An external fire must not cause virtually instantaneous explosion of almost the entire contents of the package. Insensitive explosives which have a mass explosion hazard, but are so insensitive that there is very little probability of Very insensitive explosives; 1 1.5 initiation, or of transition from burning to detonation, under blasting agents normal conditions of transport. -

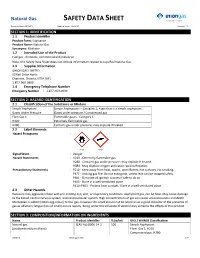

Natural Gas SAFETY DATA SHEET

Natural Gas SAFETY DATA SHEET Revision Date: 09/2015 Date of issue: 09/2015 Version: 1.1 SECTION 1: IDENTIFICATION 1.1 Product Identifier Product Form: Substance Product Name: Natural Gas Synonyms: Methane 1.2 Intended Use of the Product Fuel gas - domestic, commercial and industrial Note: this Safety Data Sheet does not include information related to Liquified Natural Gas. 1.3 Supplier Information UNION GAS LIMITED 50 Keil Drive North Chatham, Ontario, N7M 5M1 1-877-969-0999 1.4 Emergency Telephone Number Emergency Number : 1-877-969-0999 SECTION 2: HAZARD IDENTIFICATION 2.1 Classification of the Substance or Mixture Simple Asphyxiant Simple Asphyxiants – Category 1; A gas that is a simple asphyxiant. Gases Under Pressure Gases under pressure / Compressed gas Flam Gas 1 Flammable gases - Category 1 H220 Extremely flammable gas H280 Contains gas under pressure; may explode if heated 2.2 Label Elements Hazard Pictograms : GHS02 GHS04 Signal Word : Danger Hazard Statements : H220 - Extremely flammable gas. H280 - Contains gas under pressure; may explode if heated. H380 - May displace oxygen and cause rapid suffocation. Precautionary Statements : P210 - Keep away from heat, sparks, open flames, hot surfaces. No smoking. P377 - Leaking gas fire: Do not extinguish, unless leak can be stopped safely. P381 - Eliminate all ignition sources if safe to do so. P403 - Store in a well-ventilated place. P410+P403 - Protect from sunlight. Store in a well-ventilated place. 2.3 Other Hazards Exposure may aggravate those with pre-existing eye, skin, or respiratory conditions. Asphyxiant gas, can be fatal. May cause damage to the blood, central nervous system, and cardiovascular system. -

Montenegro Agenda Hazardous Activities

Identification of Hazardous Activities Identification of hazardous activities - requirements and link to the SEVESO II Directive Identification of Hazardous Activities For the purpose of implementing the Convention hazardous activities have to be identified Legal basis – Article 4(1) - the Party … shall take measures, as appropriate, to identify hazardous activities within its jurisdiction Article 1(b) - “Hazardous activity” means any activity in which one or more hazardous substances are present or may be present in quantities at or in excess of the threshold quantities listed in Annex I hereto, and which is capable of causing transboundary effects Combination of two criteria Quantity of hazardous substances over predefined thresholds Possibility of transboundary effects Identification of Hazardous Activities Hazardous substances and respective thresholds – Annex I Generic hazard categories Named substances Possibility of transboundary effects Consequence assessment according national requirements Guidelines to facilitate the identification of hazardous activities for the purposes of the Convention (Guidelines for Location Criteria) (decision 2000/3 in ECE/CP.TEIA/2, annex IV) Subject to consultation Identification of Hazardous Activities There should be mechanisms for: Collection of data on hazardous substances from operators Analysis and validation of data by the Competent Authority Review/update of data Including evaluating potential transboundary effects! Annex I of the Convention and Annex I of the SEVESO II Directive -

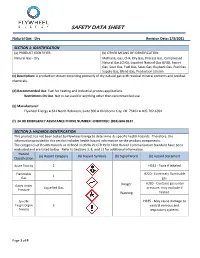

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET Natural Gas - Dry Revision Date: 2/3/2021 SECTION 1: IDENTIFICATION (a) PRODUCT IDENTIFIER: (b) OTHER MEANS OF IDENTIFICATION: Natural Gas - Dry Methane, Gas, CH4, Dry Gas, Process Gas, Compressed Natural Gas (CNG), Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), Sweet Gas, Sour Gas, Fuel Gas, Sales Gas, Buyback Gas, Fuel Gas Supply Gas, Blend Gas, Production Stream (c) Description: A production stream consisting primarily of dry natural gas with residual mineral contents and residual chemicals. (d) Recommended Use: Fuel for heating and industrial process applications. Restrictions On Use: Not to be used for anything other than recommended use. (e) Manufacturer: Flywheel Energy ● 621 North Robinson, Suite 300 ● Oklahoma City, OK 73102 ● 405-702-6991 (f) 24 HR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE PHONE NUMBER: CHEMTREC: (833) 604-8137 SECTION 2: HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION This product has not been tested by Flywheel Energy to determine its specific health hazards. Therefore, the information provided in this section includes health hazard information on the product components. The categories of Health Hazards as defined in OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200 Hazard Communication Standard have been evaluated and are listed below. Refer to Sections 3, 8, and 11 for additional information. Hazard (a) Hazard Category (b) Hazard Symbols (b) Signal Word (b) Hazard Statement Classification Acute Toxicity 2 H331 - Toxic if inhaled Flammable H220 - Extremely flammable 1 Gas gas. H280 - Contains gas under Gases Under Danger Liquefied Gas pressure; may explode if Pressure Warning heated. Specific H335 - May cause damage to Target Organ 3 central nervous and Toxicity respiratory systems. Page 1 of 9 SAFETY DATA SHEET Natural Gas - Dry Revision Date: 2/3/2021 Health Hazard Precautionary Statements (b) P210 Keep away from heat, sparks, open flames, hot surfaces. -

Appendix C. Preliminary Quantitative Risk Analysis of the Texas Clean Energy Project

Appendix C. Preliminary Quantitative Risk Analysis of the Texas Clean Energy Project PRELIMINARY QUANTITATIVE RISK ANALYSIS (QRA) OF THE TEXAS CLEAN ENERGY PROJECT Prepared For CH2M Hill 9191 South Jamaica Street Englewood, CO 80112-5946 Prepared By Quest Consultants Inc. 908 26th Avenue, N.W. Post Office Box 721387 Norman, OK 73070-8069 Telephone: 405-329-7475 Fax: 405-329-7734 November 15, 2010 10-11-6773 QUEST PRELIMINARY QUANTITATIVE RISK ANALYSIS (QRA) OF THE TEXAS CLEAN ENERGY PROJECT Table of Contents Page 1.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Hazards Identification.................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Failure Case Definition ................................................................................................ 1-2 1.3 Failure Frequency Definition ....................................................................................... 1-3 1.4 Hazard Zone Analysis ................................................................................................. 1-3 1.5 Public/Industrial Risk Quantification ........................................................................... 1-3 1.6 Risk Assessment.......................................................................................................... 1-3 2.0 Facility Location, Pipeline Routes, Pipeline Data, and Well Data ............................................. 2-1 2.1 TCEP Facility Location -

Toxicity Assessment of Combustion Gases and Development of A

DOT/FAA/AR-95/5 Toxicity Assessment of Office of Aviation Research Washington, D.C. 20591 Combustion Gases and Development of a Survival Model Louise C. Speitel Airport and Aircraft Safety Research and Development Division FAA Technical Center Atlantic City International Airport, NJ 08405 July 1995 Final Report This document is available to the U.S. public through the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), Springfield, Virginia 22161. U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturer's names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. This document does not constitute FAA certification policy. Consult your local FAA aircraft certification office as to its use. This report is available at the Federal Aviation Administration William J. Hughes Technical Center's Full-Text Technical Reports page: actlibrary.tc.faa.gov in Adobe Acrobat portable document format (PDF). Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT/FAA/AR-95/5 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date TOXICITY ASSESSMENT OF COMBUSTION GASES AND July 1995 DEVELOPMENT OF A SURVIVAL MODEL 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Louise C. Speitel 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Airport and Aircraft Safety Research and Development Division FAA Technical Center 11. -

Commonly Shipped Undeclared Hazardous Materials

Commonly Shipped Undeclared Hazardous Materials The phrase “hazardous material” or “dangerous good” means a substance or material which has been determined by the Secretary of Transportation to be capable of posing an unreasonable risk to health, safety, and property when transported in commerce. Do you own a company that ships consumer products? Do you mail holiday or birthday presents? Do you sell products online on e-commerce sites? If the answer is yes, then you should first determine whether or not the products that you’re shipping are hazardous. More than 3 billion tons of regulated Hazardous Materials—including explosive, poisonous, corrosive, flammable, and radioactive materials—are known to be transported in the United States each year. When these materials are properly manufactured, packaged, labeled, handled and stowed, they can be transported safely; however, if they are not, they can pose significant threats to property, transportation workers, emergency responders, the general and traveling public and the environment because of the potential for accidents and incidents. The shipper is responsible for properly classifying material prior to offering it into transportation. A good starting point for determining if your product might be hazardous is by obtaining a Safety Data Sheet (SDS) from the manufacturer and checking the Transportation Information section; which provides guidance on classification information for shipping and transporting of potentially hazardous materials by road, air, rail, or sea. The thought rarely crosses our minds, but many consumer goods not generally thought of as hazardous are considered hazardous materials. Hazardous materials are essential to our daily lives. We need to ship everything from urgent medical samples and medicines, to cosmetics and personal care products.