Caitlin McKenzie (n8323330) Tutor Name: Steve Badman

I am poor, therefore I will always be a statistic.

Societal and stereotypical inequities and how these perpetuate established health inequities amongst lower socioeconomic individuals.

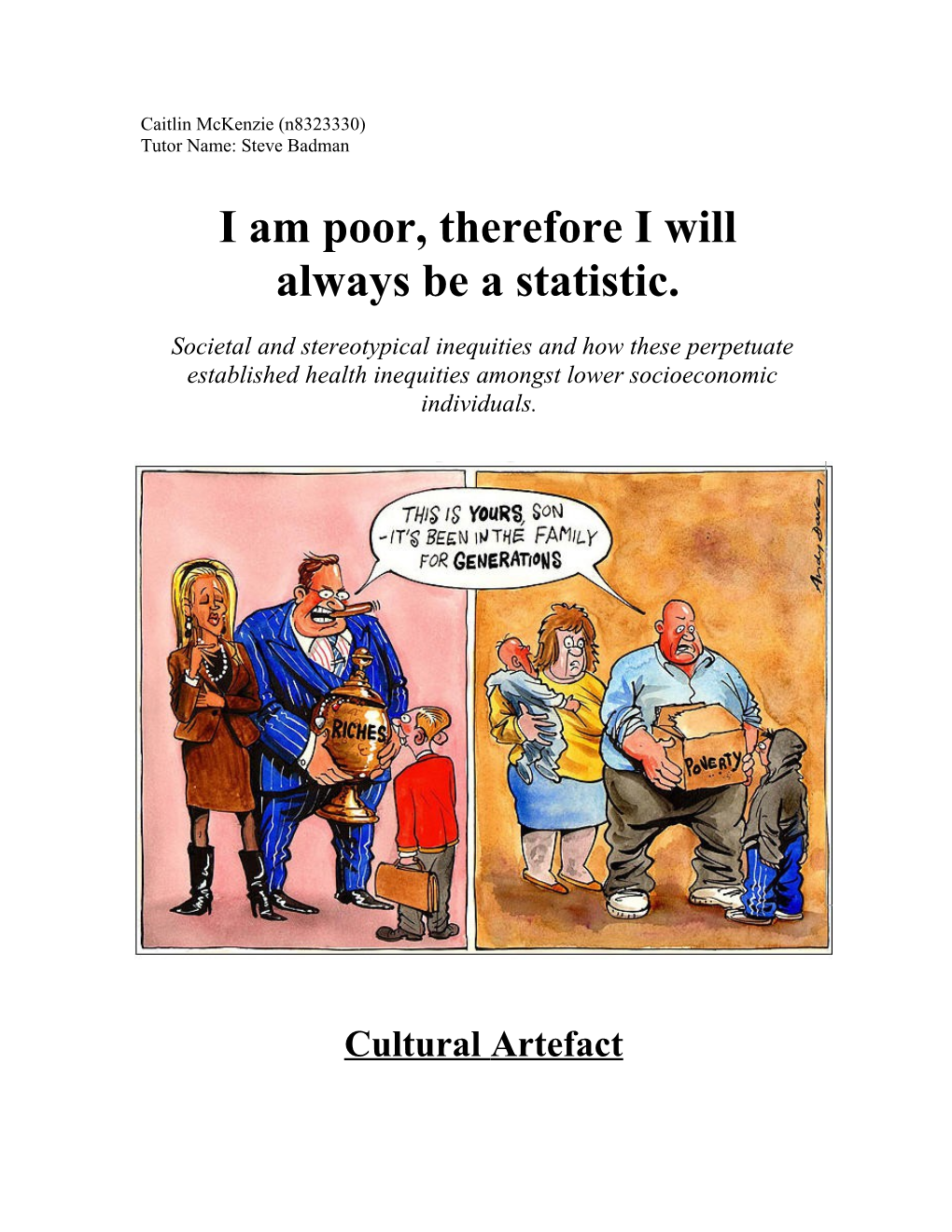

Cultural Artefact This Andy Davey cartoon (2010) was produced to illustrate the expanding poverty gap within the United Kingdom. However, it can be utilised to denote various social and cultural issues that result from economic circumstances. It visually illustrates the notion of ‘cultural practice’ or, more specifically, comments on how cultural practice defines particular groups within society. Economic status continues to determine persistent generational cultural practices and thus, concurrently, the health and life chances of individuals. The image calls into question broader themes such as society’s stereotypical views of socioeconomic status, and the stigmatisation and generalisation associated with socioeconomic grouping.

Public Health Issue

Despite generalised and stereotypical societal views of lower socioeconomic individuals, there exists a clear and undisputed correlation between low socioeconomic status and poor health. Economic status is identified as a ‘risk’ factor for individuals, and is therefore an integral public health issue which is evident within research and academic literature. Lower socioeconomic individuals have markedly lower levels of health literacy, and are noticeably overrepresented in recorded incidences of disease and mental health. It is an issue that needs to be and, can be, addressed. The perpetuation of stereotypical views of lower socioeconomic individuals can be seen to contribute to, rather than help improve, such statistics, and can therefore be viewed as a ‘contributing risk factor’ also.

Literature Review

Why does low socioeconomic status equate to health inequality?

According to Australia’s Health (2010), there exists a ‘socioeconomic gradient of health,’ meaning the position an individual occupies on the economic spectrum will ultimately indicate their level of overall health and life chance. According to this gradient, there exists a distinct correlation between lower socioeconomic status and poor health. The health disparity between lower and higher socioeconomic individuals is however, according to Roy (2004), attributed to more than ‘material conditions.’ Australia’s Health (2012) also explores this notion, commenting that issues such as social exclusion and stigmatisation are just as pertinent to an individual’s physical and psychological health as their ‘material circumstances.’

Whilst we must acknowledge ‘cultural practice’ as a statistically proven contributor to poor health, for lower socioeconomic individuals, we must also recognise that, as a group, there are overrepresented in terms of incidences of negative lifestyle choices and, consequently, overrepresented in statistics that link them to disease. For example in 2010, 25% of people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas smoked tobacco at twice the rate of people living in higher economic positions. This, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005), translated into a higher incidence of, and mortality from, lung cancer. Similarly, differences between socioeconomic positioning in regards to the prevalence of hypertension and cardiovascular disease, further illustrated this health disparity. Other risk factors, such as physical activity and nutrition showed similar patterns. Statistics of physical inactivity illustrated that lower socioeconomic individuals were 15% more inactive than those in higher socioeconomic positions, whilst 41% of lower socioeconomic individuals had inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption, compared to the 35 % of high socioeconomic individuals.

Current smokers(a) by relative socioeconomic advantage(b), Proportion of adult current smokers Figure 1

Figure 2

However, despite this statistical, cultural practice-based theory, the 32% greater burden of disease experienced by lower socioeconomic individuals in 2003, was and is attributed to more than just unhealthy lifestyle choices (Begg, Vos, Barker, Stanley & Lopez, 2008). In order to accurately understand why such an extreme health disparity exists, both physical and psychological health components need to be considered. In addition to physical health directly impacting an individual’s psychological state (Australia’s Health, 2010), it is important to recognise that economic stressors exacerbate psychological wellbeing and make individuals vulnerable to external judgements. As outlined within the ‘conceptual framework for Australia’s Health 2010’ (Figure 3) and various other health frameworks, there is an inextricable link between determinants and health and wellbeing, or more specifically, socioeconomic factors and functioning, disease, illness, life expectancy, mortality and subjective health. Perhaps the most pertinent element within this framework is subjective health, with the idea and impact of psychological health an important consideration in this regard. Figure 3 (Conceptual framework for Australia’s Health 2010)

“To be relatively poor is thus to be forced to live on the margins of society, to be excluded from the natural spheres of consumption and activity which together define social participation and national identity” (ABS, 2009).

The above definition clearly defines low socioeconomic individuals and their treatment within society, and yet disturbingly, but not surprisingly, this is the current definition of poverty within Australia. Coupled with society’s constant stigmatisation and generalisation of lower socioeconomic individuals, this can be seen to contribute to, rather than prevent or decrease, the physical health statistics previously discussed. According to Ono and Berg (2009), social stratification based on economic standing, can give or deny an individual access to desirable relationships, and therefore control their ability to enter socially and economically advantageous layers of society. The stigmatisation and consequent social exclusion and emotional stress, experienced by individuals of low socioeconomic positioning, can lead to the psychological impingement of overall health and wellbeing. Various stressors can harm health directly, with significant evidence to support the development of disease or unhealthy behaviour as a result of psychological stress. Previously discussed health problems, such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension, can be viewed as being caused by or otherwise contributing to an individual’s already established, economic-provoked health conditions. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, individuals within the most disadvantaged areas have a higher prevalence of mental and behavioral problems with 12.3% compared to 8.1%. In addition to this, the most socioeconomically disadvantaged areas had a greater proportion of people with a very high level of psychological distress compared to advantageous areas (7% compared to 2.1%). The National Health Survey identified conditions such as emotional disorders, dependence on drugs/alcohol, feelings of anxiousness and nervousness and incidences of depression as long-term mental or behavioural issues (ABS, 2010).

Very high level of psychological distress(a), By SEIFA(b)—Persons aged 18 years and over

Figure 4

The psychological disparity that exists between low and high socioeconomic individuals can be attributed to stigma and its consequent social, cultural and moral impacts. Phelan and Link (2006) state that stigma places individuals at a substantial social disadvantage, increasing their exposure to risks and limiting their access to protective factors. Societal perception and treatment of low socioeconomic individuals, therefore potentially increases the burden of disease or disability. For each physical health issue and cultural practice, a psychological element is apparent. For example individuals who experience high levels of psychological distress are more likely to be daily smokers (31%) than those who experience low levels of psychological distress (16%). Also, lower socioeconomic individuals who have been statistically proven to rate their health as inadequate or low/poor can, to a degree, be reflecting the perceptions of others, and thus embodying the behaviour that others expect of them. How an individual feels about themselves and their life chances is profoundly impacted by stigmatisation and the perception of oneself by others (White & Wynn, 2008). An individual can be easily constrained by their reputation or social label, influencing feeling of self perception. Australia’s Health (2010) confirms this, stating that an individual’s underlying attitudes and beliefs interact with many other factors that can influence their health behaviours. Thus, it is likely that lower socioeconomic individuals will adopt societal perceptions, allowing this to inform their self beliefs and attitudes and, as a result, they will come to embody ‘expected’ or ‘perceived’ behaviours (as determined by wider society).

Aneshensel (1992) discusses the concept of social support and its relation to psychological function. According to Aneshensel, social support is defined in terms of an individuals basic social needs: affection, esteem, approval, belonging, identity and security. However, for lower socioeconomic individuals, these social needs are compromised as a result of societal stigmatisation. Individuals are socially excluded, subjected to gross generalisations and considered inferior, thus all modes of social support, or more notably societal support, are removed. Emotional and perceived social support acts as a buffer to the health impacts of stress. Therefore, in the absence of social support, issues of stress manifest into psychological distress and concurrent physical health issues. In addition to this, Chen (2012) suggests that ‘shift and persist’ strategies are adopted and implemented by lower socioeconomic individuals, which enable them to accept stress and adapt to it, whilst utilising optimism to overcome challenges. However, this coping mechanism appears to be statistically void, and whilst this strategy may be implemented by socioeconomic individuals, the psychological impacts associated with their economic positioning may be greater than their ability to overcome them. Statistical evidence regarding health literacy is also particularly alarming and illustrates an overt correlation between socioeconomic status and level of health knowledge. Of individuals living in lower socioeconomic areas, 26% were identified as having ‘adequate’ health literacy, compared to 55% of individuals within higher socioeconomic areas. Individuals were also more likely to identify their own health as being ‘relatively low,’ if they resided in disadvantaged areas, were unemployed, or of Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander origin. Similar patterns were also evidenced in 2007-8 (Figure 6). Low health literacy has detrimental and continuing effects; those at a less than adequate level are more likely to be unable to effectively manage their health, and therefore are at a greater risk of adverse health outcomes (Australia’s Health, 2012).

Figure 5 (Level of Health Literacy and Socioeconomic Status)

Figure 6 Cultural and Social Analysis

Goffman’s Social Theory of Stigma Erving Goffman’s social theory of stigma (1963) effectively represents the societal stigmatisation of lower socioeconomic individuals. According to Jacoby, Snape and Baker (2005) Goffman viewed stigma as being an ‘undesired differentness,’ in the sense that individuals possessed ‘undesired attributes’ and that these attributes were the foundation of stigmatisation. Each individual was thought to have a virtual and actual identity. Virtual social identity is defined as the assumption and anticipations that we make ‘in effect’ about people on the basis of first experience, whilst actual social identity is the category and attributes that experience proves a person to possess (Smith, 2006). There is potential for disruption when these two identities are incongruent or discrepant, and if this discrepancy works to discredit or downgrade intial anticipations, rather than to elevate them, then stigmatisation occurs.

For lower socioeconomic individuals, a discrepancy between ‘actual’ identity and ‘cultural stereotypical’ identity has resulted in stigmatisation and generalisation by society. These stereotypical perceptions are characterised by a misinformed understanding of lower socioeconomic positioning and disregard for individual circumstance. This form of societal stigmatisation highlights Goffman’s second type of stigma: ‘character faults and blemishes.’ White and Wynn (2008) state that lower socioeconomic individuals are regarded by society as “morally corrupt…a threat to the economic fibre of the nation…and a threat to society’s standards of decency and respectability” (p. 22). White and Wynn’s research ultimately illustrates that an attitude of moral superiority is prevalent amongst higher economic individuals.

As stated by Goffman, stigmatised individuals are viewed as legitimate targets for discrimination, and thus the individuals responsible for such stigmatisation construct an ideology to explain their inferiority. For lower socioeconomic individuals, feelings and actions associated with poverty are cyclical, and there exists an inability to overcome economic and societal obstacles and to therefore exit this cyclical process. Stigmatised individuals may try and rid themselves of this stereotypical social identity; however, according to Goffman, they cannot reacquire the status of ‘normal,’ only that of one who is ‘contaminated’ (Jacoby et al, 2005).

Link & Phelan’s Stigmatisation Model According to Link and Phelan (2001), stigma occurs when labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination co-occur in a situation of power imbalance (Alvarado Chavarría, 2012). Their model of stigmatisation can be utilised to illustrate the power imbalance between lower and higher socioeconomic individuals within society. They propose that a ‘context of unequal power’ allows one group to enact significant societal consequences over another for carrying a ‘stigmatised label’ (Alvarado Chavarría, 2012). Similar to Goffman’s idea of ‘contamination,’ Link and Phelan discuss an individual’s inability to rid themselves of this stigmatised label. Power is considered ‘unidirectional’ and the stigmatised group cannot reverse their stigmatisation, nor attempt to stigmatise the dominant group. Link and Phelan conclude that status loss and discrimination is a consequence of negative labeling and stereotyping, and that being linked to ‘undesired characteristics,’ as worded by Goffman, reduces a person to lower status within societal hierarchies. The diminished social status, as a result of stigmatisation, puts an individual at a disadvantage, negatively effecting opportunity and thus life chances (Alvarado Chavarría, 2012).

Goffman, Link and Phelan’s theories and models demonstrate and confirm the existence of stigmatisation and its impact. They provide a framework which helps to guide our understanding, allowing us to acknowledge the existence and health implications of social inequality. Importantly, it forces us to recognise that society itself is the primary cause of stigmatisation in society. Not all individuals are equally affected by it because the stigmatisation itself stems from socioeconomic difference. Analysis of the artifact and reflection on learning

The artefact chosen is a simply, yet powerful means of demonstrating the way in which socioeconomic inequality in perpetuated. The divided image indicates the marked disparity between low and high socioeconomic status, and the attitude of inevitability of one’s placing in society. Whilst the image does not refer specifically to ‘health,’ it does indicate that a whole range of issues linked to status, including education, employment and health, are ‘passed down’ through the generations. It is indicated that generational cultural practice is ‘just what happens’ – we view the passing down of the burden of social exclusion, stigmatisation, and numerous physical and psychological inequalities as ‘the norm.’ To write off such obvious statistical patternings is to allow social injustice to occur, and to continue to occur.

As a future health professional, not only is it crucial that I am constantly aware of stigmatisation in regards to my professional interactions with clients, including the use of discriminating language and attitudes. More notably, however, it is important that I am aware of stigmatisation and its clear impacts upon health behaviour and health outcomes. In exploring social and health inequalities through epidemiological and theoretical evidence, I have furthered my knowledge and understanding of such issues, yet at the same confirmed my feelings towards stigmatisation and inequality.

References

Alvarado Chavarria, M.J. (2012). Let's try to change it: Psychiatric stigmatization, Consumer/Survivor activism, and the link and phelan model. Portland State University. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 272. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1029069859?accountid=13380 Aneshensel, C. (1992). Social stress: Theory and research. Review of Sociology, 18 15-38. Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Cardiovascular disease in Australia: A snapshot, 2004-2005 (No.4821.0.55.001). Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4821.0.55.001 Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Facts at your fingertips: Health 2011 (No.4841.0). Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/4841.0Chapter32011 Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2003). Health risk factors (No.4812.0). Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4812.0 Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2003). National health survey: Mental health (No.4811.0). Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4811.0 Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Tobacco smoking in Australia: A snapshot, 2004- 2005 (No.4831.0.55.001). Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4831.0.55.001 Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2010). Australia’s Health 2010. Retrieved from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare website http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468376 Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Australia’s Health 2012. Retrieved from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare website http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737422172 Begg, S., Vos, T., Barker, B., Stanley, L., & Lopez, A. (2008). Burden of disease and injury in Australia in the new millennium: measuring health loss from diseases, injuries and risk factors. Medical Journal of Australia, 188(1) 36-40. Berg, J., & Ono, H. (2009). Socioeconomic status. In H. Reis, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships. (pp. 1575-1579). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412958479.n518 Chen, E. (2012). Protective factors for health among low-socioeconomic status individuals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3) 189-193. doi: 10.1177/0963721412438710. Jacoby, A., Snape, D., & Baker, G. (2005). Epilepsy and social identity: the stigma of a chronic neurological disorder. Lancet Neural, 4 171-178. Link, B., & Phelan, J. (2006). Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet, 367 528- 529. Mattaini, M. (1996). The new frontier: A review of changing cultural practices: a Contextualist framework for intervention research. The Behaviour Analyst 19(1), 135-141. Roy, J. (2004). Socioeconomic status and health: A neurobiological perspective. Medical Hypotheses, 62 222-227. Smith, G. (2006). Erving Goffman [EBL version]. Retrieved from http://www.qut.eblib.com.au.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx? p=273734 Wardle, J., Steptoe, A. (2003). Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. Journal of epidemiol community health 57(6), 440-443. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.440 White, R., & Wynn, J. (2008). Youth and Society (2nd ed.). Victoria, Australia: Oxford University Press.