4. d. Taxes

A tax is defined as being a contribution made by individuals, groups, and businesses to support the government of the region within which they reside. Taxes are used by the government to increase revenue for community projects such as streets and schools – all in attempt to better the lives and living conditions of the general public.

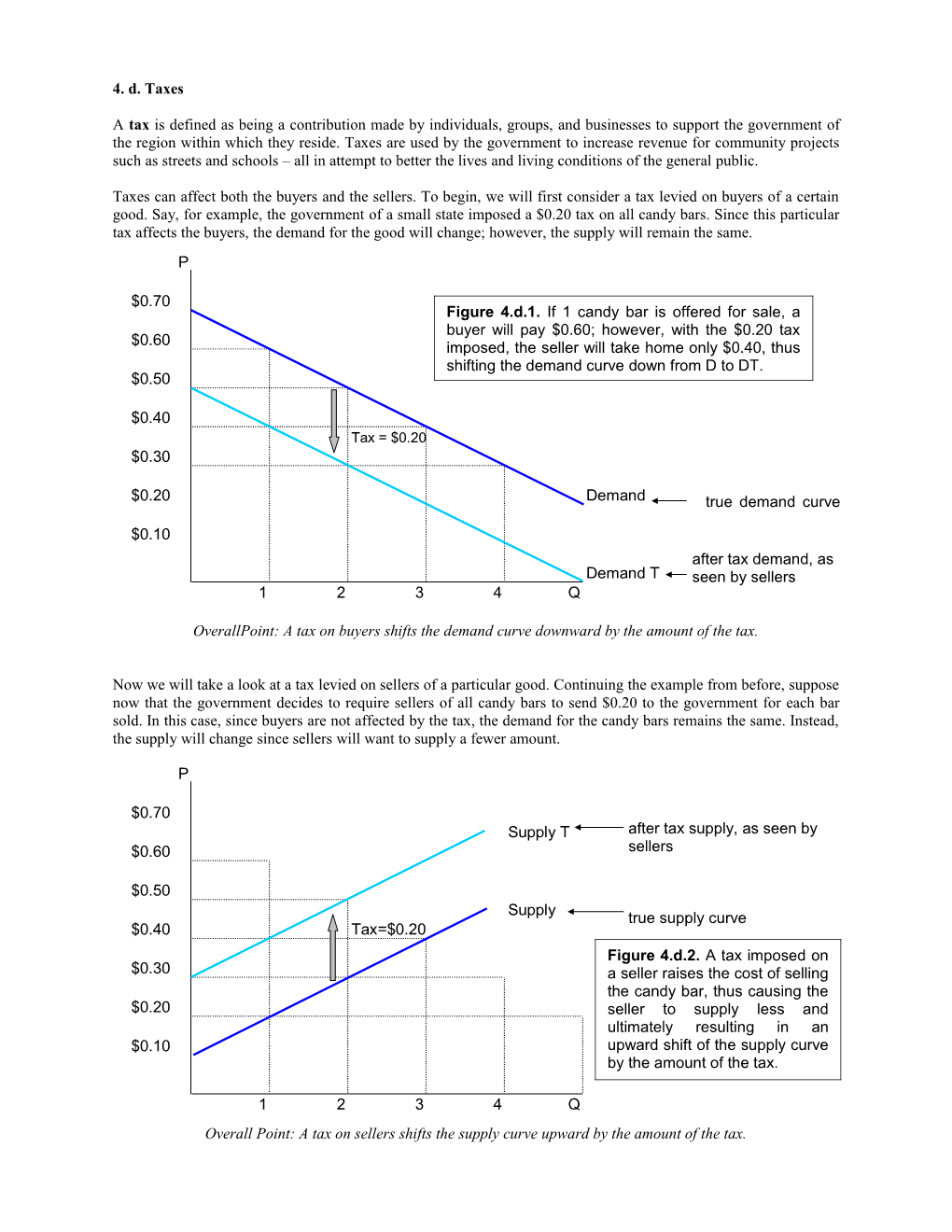

Taxes can affect both the buyers and the sellers. To begin, we will first consider a tax levied on buyers of a certain good. Say, for example, the government of a small state imposed a $0.20 tax on all candy bars. Since this particular tax affects the buyers, the demand for the good will change; however, the supply will remain the same. P

$0.70 Figure 4.d.1. If 1 candy bar is offered for sale, a buyer will pay $0.60; however, with the $0.20 tax $0.60 imposed, the seller will take home only $0.40, thus shifting the demand curve down from D to DT. $0.50

$0.40 Tax = $0.20 $0.30

$0.20 Demand true demand curve

$0.10 after tax demand, as Demand T seen by sellers 1 2 3 4 Q

OverallPoint: A tax on buyers shifts the demand curve downward by the amount of the tax.

Now we will take a look at a tax levied on sellers of a particular good. Continuing the example from before, suppose now that the government decides to require sellers of all candy bars to send $0.20 to the government for each bar sold. In this case, since buyers are not affected by the tax, the demand for the candy bars remains the same. Instead, the supply will change since sellers will want to supply a fewer amount.

P

$0.70 Supply T after tax supply, as seen by $0.60 sellers

$0.50 Supply true supply curve $0.40 Tax=$0.20 Figure 4.d.2. A tax imposed on $0.30 a seller raises the cost of selling the candy bar, thus causing the $0.20 seller to supply less and ultimately resulting in an $0.10 upward shift of the supply curve by the amount of the tax.

1 2 3 4 Q Overall Point: A tax on sellers shifts the supply curve upward by the amount of the tax. The following is an example of a particular good with a $0.08 tax imposed on it. The figure below illustrates the amount of tax paid by the buyers and the sellers as well as the dead weight losses that result.

P

Tax paid by buyers = $0.05 x 10 = $0.50 DWL-CS = $0.05 x 2 x .5 = $0.05

$1.08=Pb S

$1.03=P* DWL-PS = $0.03 x 2 x .5 = $0.03

$1.00=Ps

D Tax paid by sellers = tax=$0.08 $0.03 x 10 = $0.30

DT Qt=10 Q*=12 Q

Figure 4.d.3. The fair market value of this good was $1.03 (P*). The $0.08 tax imposed drove the price the buyers will pay up to $1.08 (Pb). In this case, the seller will only receive $1.00 for each good sold (Ps). As a result, the buyers will end up paying more tax than the sellers and therefore, the DWL incurred by consumer surplus is also greater than the DWL incurred by producer surplus. As a whole, the government gains $0.80 in tax revenue (buyers tax + sellers tax = $0.50 + $0.30).

In the previous example, the buyers ended up paying more tax than the sellers – which brings us to a question: What do tax burdens depend on? Well the answer is simple – it all depends upon the slopes of the demand and supply curves.

CASE 1: Demand Curve is flatter. When the demand curve is flatter (less steep) than the supply curve, the buyers pay less tax and the sellers pay more tax. Thus, there is a greater producer DWL than consumer. P

Buyers Tax

DWL-CS S Figure 4.d.4. The yellow and pink regions of the graph are areas lost by Pb buyers and sellers but P* DWL-PS gained by the government. The DWL’s are lost forever. As you can tell, the buyers pay less tax than the sellers. Ps D Sellers tax

DT Qt Q* Q Tax CASE 2: Supply Curve is flatter. When the supply curve is flatter (less steep) than the demand curve, the buyers pay more tax than the sellers. Therefore, the DWL experienced by consumers is greater.

P

Buyers Tax DWL-CS Figure 4.d.5. The yellow and pink regions of the ST graph are the areas lost by buyers and sellers Pb tax but gained by the S government. The DWL’s P* are lost forever. In this Ps DWL-PS case, the sellers pay less tax than the buyers. Sellers Tax D

Qt Q* Q

Overall Point: whoever has the flatter line pays less tax.

In this next example, the focus is on the taxation with a fixed supply. Suppose there is a particular area of historical importance where nothing new can be built and nothing old can be torn down. In this area, there is a total of 100 apartments, each going for about $800. However, the city imposed a $200 tax on each apartment.

P

Figure 4.d.6. When the government Tax paid only by sellers = imposes a $200 tax, the rental price $20,000 of the apartment remains the same. S However, the sellers are the ones who must pay this tax, not the buyers. There is also NO DWL when there is a fixed supply. $800=P*=Pb

D $600=Ps tax=$200

DT 100 Q A particular type of tax is called a tariff. A tariff is a tax on imported goods. Tariffs generally help the governments of larger countries rather than smaller countries. Outlined below is an example dealing with the importation of Toyotas into the US and New Zealand from Japan.

US-big market Tariff = $5000 P

Buyers Tax = $30K Figure 4.d.7. With the tariff, there is a $5K difference DWL-CS (US) = $3K between what the buyers pay S and what the sellers get. The US, as a whole, gains the $23K=Pb sellers tax but loses the DWL- CS; therefore, resulting in an $20K=P* DWL-PS overall gain of $17K ($20 - $3). (Japan) = $18K=Ps $2K

tax D

DT 10 12 Q Sellers Tax (Japan) = $20K

New Zealand-small market Tariff = $5000 P

Tax paid by NZ buyers

DWL-CS (NZ) = $15K $25K=Pb Figure 4.d.8. New Zealand ends up losing the DWL-CS area of $15K but does not gain anything. $20K=P*=Ps

tax D DT

10 16 Q Since the US has a bigger market, Japanese automakers will prefer to sell their cars to the US rather than New Zealand. Therefore, the fair market value of a car sold in the US is the same the fair market value and the price the sellers have to pay in New Zealand. As a result, New Zealand buyers must pay more than US buyers for the same vehicle. New Zealand has higher tariffs than the US in order to maintain NZ reserves of US dollars. Another aspect of taxation is the mathematical aspect. With the use of simple algebra, it is easy to a calculate the equilibrium point. After figuring out the equations that satisfy both the demand and supply curves, set them equal to each other, and solve for the missing value.

Example:

P

Figure 4.d.9. Here, the demand curve S follows the equation 8-Q and the supply curve 2+2Q. Step 2: 8-Q = 2+2Q and 10 solve for Q. In the end, Q=2 and by plugging this value of Q back in the D 8 and S equations, you can easily get the value for P. Thus, the equilibrium lies at points (Q,P). 6 Equilibrium point (2,6) 4

2

D 2 4 6 8 Q

Step 1: D: P = 8 – Q S: P = 2 + 2Q

Step 2: Set D and S equal to each other and solve for Q. 8 – Q = 2 + 2Q 6 = 3Q 2 = Q

Step 3: Plug the obtained value of Q back into the D and S equations and solve for P. D: P = 8 – 2 P = 6 S: P = 2 + 2(2) P = 6

Step 4: Plot equilibrium point on graph. Since Q = 2 and P = 6, the equilibrium point is (2,6).

The same method applies when there either an ST or a DT curve are used as opposed to the regular S and D curves.