The Complete Macdiarmid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter Scott and the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 5 2007 "A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott nda the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement Margery Palmer McCulloch University of Glasgow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McCulloch, Margery Palmer (2007) ""A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott nda the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 44–56. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Margery Palmer McCulloch "A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott and the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement Edwin Muir's characterization in Scott and Scotland (1936) of "a very cu rious emptiness .... behind the wealth of his [Scott's] imagination'" and his re lated discussion of what he perceived as the post-Reformation and post-Union split between thought and feeling in Scottish writing have become fixed points in Scottish criticism despite attempts to dislodge them by those convinced of Muir's wrong-headedness.2 In this essay I want to take up more generally the question of twentieth-century interwar views of Walter Scott through a repre sentative selection of writers of the period, including Muir, and to suggest pos sible reasons for what was often a negative and almost always a perplexed re sponse to one of the giants of past Scottish literature. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

Hugh Macdiarmid, Author and Publisher J.T.D

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 7 1986 Hugh MacDiarmid, Author and Publisher J.T.D. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hall, J.T.D. (1986) "Hugh MacDiarmid, Author and Publisher," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 21: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol21/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J.T.D. Hall Hugh MacDiarmid, Author and Publisher In his volume of autobiography, Lucky Poet, Hugh MacDiarmid declared that at an early age he had decided that his life's work would not follow a conventional pattern and would exist outside the scope of ordinary professional activities: I was very early determined that I would not 'work for money', and that whatever I might have to do to earn my living, I would never devote more of my time and my energies to remunerative work than I did to voluntary and gainless activities, and actes gratuits, in Gide's phrase.1 It is perhaps not surprising that his chosen field was literature. In the same volume, MacDiarmid claimed that a "literary strain" had been struggling to the fore over several generations on both sides of the family. If his home background was thus conducive to literature, he also found ample encouragement in the resources of the local library in Langholm which were available to him, and which he consumed with an omnivorous appetite.2 Early writings were occasionally rewarded by prizes in literary competitions, or accorded the ultimate accolade of publication.3 MacDiarmid's teachers at Broughton School were aware of his great talents, and 54 J.T.D. -

Reconstruction of a Gaelic World in the Work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh Macdiarmid

Paterson, Fiona E. (2020) ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/81487/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid Fiona E. Paterson M.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2020 Abstract Neil Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid are popularly linked with regards to the Scottish Literary Renaissance, the nation’s contribution to international modernism, in which they were integral figures. Beyond that, they are broadly considered to have followed different creative paths, Gunn deemed the ‘Highland novelist’ and MacDiarmid the extremist political poet. This thesis presents the argument that whilst their methods and priorities often differed dramatically, the reconstruction of a Gaelic world - the ‘Gaelic Idea’ - was a focus in which the writers shared a similar degree of commitment and similar priorities. -

\223Hugh Macdiarmid\224 Was the Pseudonym Used by the Critic Christ

Papers on Joyce 5 (1999): 3-13 “A Joyce Tae Prick Ilka Pluke”: Joyce and the Scottish Renaissance DAVID CLARK Universidade da Coruña For the writers of the movement which came to be known as the Scottish Literary Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s, Joyce, as the most outstanding figure in contemporary Irish letters, stood as an obligatory point of reference. If Joyce greatly influenced writers throughout the world, this influence was doubly felt in small countries like Galicia and Scotland which considered themselves to be historically and culturally linked in some way to Ireland. 1 Irish literature in general marked the ideal state to which the Renaissance writers aspired for Scotland, and Joyce provided the bridge between tradition and modernity which they considered necessary for the regeneration of Scottish culture in the face of the desired political independence. Within such a framework, the novelist Neil Gunn and the poet Hugh MacDiarmid both hailed Joyce as the prototype for a resurgence in Scottish letters, offering at times a distorted perspective of Joyce’s work in order to comply with their wider pragmatic vision. “Hugh MacDiarmid” was the pseudonym used by the critic Christopher Grieve, a literary maverick who thrived on controversy and who represents, without a doubt, the most important figure of Scottish letters that the twentieth century has produced, both for his own massive, heterogeneous, if somewhat erratic, literary output and also for the enormous influence he had on the Scottish writers of his own and of succeeding generations. Grieve had been impressed by the fragments of Ulysses which had been published in the Little Review , edited by Margaret Anderson, from 1918, and had been able to obtain one of Sylvia Beach’s 1,000 copy limited edition of the finished work on publication. -

SCOTTISH LITERARY RENAISSANCE: from HUGH MACDIARMID to TOM LEONARD, EDWIN MORGAN and JAMES ROBERTSON A

ТEME, г. XLIV, бр. 4, октобар − децембар 2020, стр. 1549−1562 Оригинални научни рад https://doi.org/10.22190/TEME201008093K Примљено: 8. 10. 2020. UDK 821.111'282.3(414).09-1"19" Ревидирана верзија: 5. 12. 2020. Одобрено за штампу: 5. 12. 2020. SCOTTISH LITERARY RENAISSANCE: FROM HUGH MACDIARMID TO TOM LEONARD, EDWIN MORGAN AND JAMES ROBERTSON a Milena Kaličanin University of Niš, Faculty of Philosophy, Niš, Serbia [email protected] Abstract The paper deals with the Scottish literary revival that occurred in the 1920s and 1930s. The leading theoretical and artistic figure of this movement was Hugh MacDiarmid, a Scottish poet whose main preoccupation was the role of Scots and Gaelic in shaping modern Scottish identity. Also called the Lallans revival – the term Lallans (Lowlands) having been used by Robert Burns to refer solely to the notion of language, the movement’s main postulates included the strengthened cultural liaisons between Scots and Gaelic (and not Scots and English as was the case until then). In the preface to his influential anthology of Scottish poetry, The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse (1941), MacDiarmid bluntly stated that the prime aim of Scottish Literary Renaissance was to recharge Scots as a stage in the breakaway from English so that Scottish Gaelic heritage could properly be recaptured and developed. Relying primarily on MacDiarmid’s theoretical insights, it is our purpose to track, explore and describe the Scottish Literary Renaissance’s contemporary echoes. The paper thus focuses on the comparative analysis of Hugh MacDiarmid’s poetry, on the one hand, and the poetry of its contemporary Scottish creative disciples (Tom Leonard, Edwin Morgan and James Robertson). -

The Asymmetry of British Modernism: Hugh Macdiarmid and Wyndham Lewis', Modernist Cultures, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Asymmetry of British Modernism Citation for published version: Thomson, A 2013, 'The Asymmetry of British Modernism: Hugh MacDiarmid and Wyndham Lewis', Modernist Cultures, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 252-271. https://doi.org/10.3366/mod.2013.0064 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/mod.2013.0064 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Modernist Cultures Publisher Rights Statement: © Thomson, A. (2013). The Asymmetry of British Modernism: Hugh MacDiarmid and Wyndham Lewis. Modernist Cultures, 8(2), 252-271. 10.3366/mod.2013.0064 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 The Asymmetry of British Modernism: Hugh MacDiarmid and Wyndham Lewis Alex Thomson Devolution in the United Kingdom has begun to affect our understanding of modern literary history, if only because the tendency silently to conflate English with British has been made increasingly problematic. This is particularly marked in the case of Scotland. -

Roseanne Watt

AA MY MINDIN: MOVING THROUGH LOSS IN THE POETIC LITERARY TRADITION OF SHETLAND Roseanne Watt Division of Literature and Languages University of Stirling Scotland UK Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Abstract Shetland literature is often defined by loss – the loss of language, of a way of life, of a place within time itself. Shetland writers have historically responded to this landscape of loss through a stringent need for the preservation of tradition. This thesis is an attempt to understand that response, and to frame my own creative practice in dialogue with this tradition, whilst trying to create something new within it. In particular I will discuss the influence of Norn on this narrative of loss, and how the language came to be framed in death has contributed to this atmosphere of loss and desire for preservation. The Shetland poet Robert Alan Jamieson has written eloquently and insightfully on these matters; as such, the bulk of this thesis is given over to a critical reading of his collections, with a view to understanding his response, and through this coming to an understanding my own. Part of this thesis is creative practice, and the films produced in that regard can be viewed online following instructions contained within; the final part of the thesis is a critical framing of this practice using the framework built by the thesis prior to that point. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, to my supervisors, Professor Kathleen Jamie and Dr Sarah Neely; your encouragement, knowledge, enthusiasm and kindness over the years has helped me gain confidence in my own abilities as a writer and filmmaker, allowing me to produce work which I am very proud of. -

Hugh Macdiarmid in Context

Hugh MacDiarmid in Context Alan Riach Hugh MacDiarmid died in 1978. I met him three times during the last year of his life, here at Brownsbank, when he was in his mid-80s. He was one of the very great poets of the twentieth century and he brought about enormous and difficult changes in his native country. He came out of the nineteenth century. He was born in the Scottish Borders in 1892. He served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in the First World War. He survived that and was relieved from service suffering from cerebral malaria. He survived that and became a full-time journalist in Scotland, but when his first marriage broke down he suffered extreme psychological alienation and physical breakdown. He survived these. With his second wife and a young son he went to live on the Shetland island of Whalsay, far north of mainland Scotland. Their staple food was mackerel and mushrooms. He survived that, returning to Glasgow during World War II. Surviving that, he and his wife settled in the Borders once again. Throughout his adult life, his voice was raised in protest at injustice and inadequacy everywhere, but especially in Scotland: and so he made a lot of enemies. He was a lyric poet, a satirical poet, a meditative and philosophical poet, and finally an epic poet. He lived in relative poverty for most of his long life. He came out of the nineteenth century – literally. He came out of a world in which certain individual men had taken upon themselves a kind of comprehensive understanding of society, an attempt to understand the workings of the social world in all their complexity: the great Victorian sages, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Matthew Arnold. -

TOCC0547DIGIBKLT.Pdf

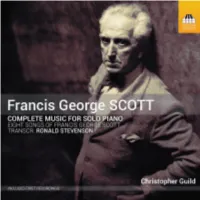

FRANCIS GEORGE SCOTT Complete Piano Music Eight Songs of Francis George Scott (transcribed by Ronald Stevenson)* 23:22 1 No. 1 Since all thy vows, false maid, are blown to air 3:30 2 No. 2 Wha is that at my bower-door? 2:17 3 No. 3 O were my love yon lilac fair 3:20 4 No. 4 Wee Willy Gray 1:37 5 No. 5 Milk-Wort and Bog-Cotton 3:05 6 No. 6 Crowdieknowe 3:09 7 No. 7 Ay Waulkin, O 3:50 8 No. 8 There’s news, lasses, news 2:34 9 Urlar (5 October 1948) 3:06 10 April Skies (? 1912) 6:19 Intuitions 37:12 11 No. 1 Lullaby. Grave (undated) 0:41 12 No. 2 Trumpet Tune. Allegro moderato (undated) 0:17 13 No. 3 Lonely Tune. Andantino (undated) 0:48 14 No. 4 Running Tune. Animato (10 May 1943) 0:24 15 No. 5 Lilting Tune. Andante (14 October 1943) 0:35 16 No. 6 National Song. Andante (25 February 1944) 0:42 17 No. 7 An Clarsair. Grave (13 September 1944) 0:56 18 No. 8 Singing Game. Presto (27 September 1944) 0:21 19 No. 9 Strathspey. Moderato (3 October 1944) 0:28 20 No. 10 Processional. Comodo (19 October 1944) 1:10 21 No. 11 Love’s Question and Reply (Dialogue). Andantino (28 October 1944) 0:42 22 No. 12 Border Riding-Rhythm. Animato (12 December 1944) 0:37 23 No. 13 Old Irish! Andantino (7 February 1945) 0:44 24 No. 14 Deil’s Dance. -

Urban Scotland in Hugh Macdiarmid's Glasgow Poems

Béatrice Duchateau Université de Bourgogne Urban Scotland in Hugh MacDiarmid’s Glasgow poems Hugh MacDiarmid is nowadays considered to be one of the greatest Scottish poets of the twentieth century. His poems, books and articles paved the way for the Scottish Renaissance and participated in the modernist movement. Although MacDiarmid is sometimes still thought a parochial poet, probably due to the fact that his work on urban pre- dicaments has been largely forgotten, he dealt at length with the city of Glasgow in the 1930s. On the isle of Whalsay (Shetland), in 1934, facing financial difficulties and a nervous breakdown, he “was writing a new long poem, to be titled “The Red Lion”, projected as an urban counter- part to A Drunk Man, dealing with the slums of Glasgow and the whole range of contemporary working class” (Bold, 1990, p. 373). In 2005, the independent Scottish scholar and poet John Manson made new discove- ries about this planned Glasgow sequence: “The Red Lion” was never published in full and it may now be impossible to discover all the constituent parts which were intended and “their proper setting” […]. “In the Slums of Glasgow” and “Nemertes” were published in 1935. “Third Hymn to Lenin” and “The Glass of Pure Water” were both originally seen as “Glasgow” poems and parts of “The Red Lion”. Several poems entitled “Glasgow” and “Glasgow is like the Sea” also belong to the project. (J. Manson, 2005, pp. 123–4) In 2007, John Manson discovered the existence of a typed manuscript entitled “Glasgow 1938” in the University of Delaware Library, USA: it is a 20-page long poem with annotations by MacDiarmid himself.