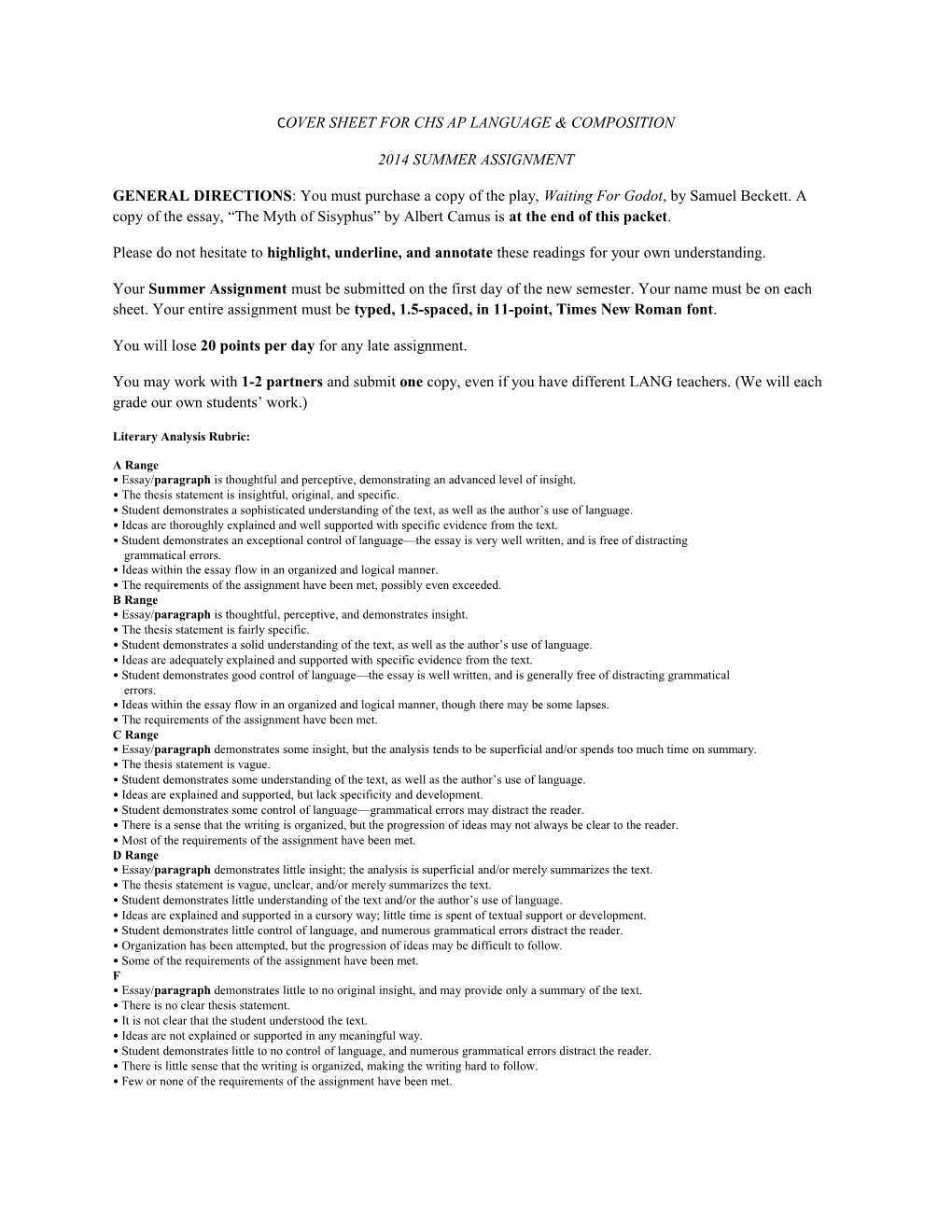

COVER SHEET FOR CHS AP LANGUAGE & COMPOSITION

2014 SUMMER ASSIGNMENT

GENERAL DIRECTIONS: You must purchase a copy of the play, Waiting For Godot, by Samuel Beckett. A copy of the essay, “The Myth of Sisyphus” by Albert Camus is at the end of this packet.

Please do not hesitate to highlight, underline, and annotate these readings for your own understanding.

Your Summer Assignment must be submitted on the first day of the new semester. Your name must be on each sheet. Your entire assignment must be typed, 1.5-spaced, in 11-point, Times New Roman font.

You will lose 20 points per day for any late assignment.

You may work with 1-2 partners and submit one copy, even if you have different LANG teachers. (We will each grade our own students’ work.)

Literary Analysis Rubric:

A Range • Essay/paragraph is thoughtful and perceptive, demonstrating an advanced level of insight. • The thesis statement is insightful, original, and specific. • Student demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the text, as well as the author’s use of language. • Ideas are thoroughly explained and well supported with specific evidence from the text. • Student demonstrates an exceptional control of language—the essay is very well written, and is free of distracting grammatical errors. • Ideas within the essay flow in an organized and logical manner. • The requirements of the assignment have been met, possibly even exceeded. B Range • Essay/paragraph is thoughtful, perceptive, and demonstrates insight. • The thesis statement is fairly specific. • Student demonstrates a solid understanding of the text, as well as the author’s use of language. • Ideas are adequately explained and supported with specific evidence from the text. • Student demonstrates good control of language—the essay is well written, and is generally free of distracting grammatical errors. • Ideas within the essay flow in an organized and logical manner, though there may be some lapses. • The requirements of the assignment have been met. C Range • Essay/paragraph demonstrates some insight, but the analysis tends to be superficial and/or spends too much time on summary. • The thesis statement is vague. • Student demonstrates some understanding of the text, as well as the author’s use of language. • Ideas are explained and supported, but lack specificity and development. • Student demonstrates some control of language—grammatical errors may distract the reader. • There is a sense that the writing is organized, but the progression of ideas may not always be clear to the reader. • Most of the requirements of the assignment have been met. D Range • Essay/paragraph demonstrates little insight; the analysis is superficial and/or merely summarizes the text. • The thesis statement is vague, unclear, and/or merely summarizes the text. • Student demonstrates little understanding of the text and/or the author’s use of language. • Ideas are explained and supported in a cursory way; little time is spent of textual support or development. • Student demonstrates little control of language, and numerous grammatical errors distract the reader. • Organization has been attempted, but the progression of ideas may be difficult to follow. • Some of the requirements of the assignment have been met. F • Essay/paragraph demonstrates little to no original insight, and may provide only a summary of the text. • There is no clear thesis statement. • It is not clear that the student understood the text. • Ideas are not explained or supported in any meaningful way. • Student demonstrates little to no control of language, and numerous grammatical errors distract the reader. • There is little sense that the writing is organized, making the writing hard to follow. • Few or none of the requirements of the assignment have been met. SHORT RESPONSE QUESTIONS ON SAMUEL BECKETT”S PLAY, WAITING FOR GODOT:

Directions: Answer each of the following questions in 1 paragraph. (A paragraph is 8-12 sentences):

1. Waiting for Godot has been written about by many critics. Using Ebscohost, research, summarize and/or contrast two critics’ views of the play. Include your two citations at the end, please.

2. Do you think that Waiting for Godot has any religious implications? Explain. Can you persuade us that Waiting for Godot is mainly a fable?

3. FORM: The method of arrangement or manner of coordinating elements in a literary composition. STRUCTURE: the arrangement of and relations between the parts or elements of something complex. (like a play). Describe the form and structure of Waiting for Godot.

4. What is the significance of the silencing of Lucky by Pozzo and the tramps? What opinion have you formed of the two tramps? What do you think they symbolize? Compare and contrast the various relationships in Waiting for Godot.

5. To what extent is it correct to interpret Waiting for Godot as a clash between Society and the Outsider?

6. Samuel Beckett sub-titled his play, Waiting for Godot, as a “tragicomedy”. How appropriate is it to describe the play in this way? Do you subscribe to the view that Waiting for Godot ultimately tends to enhance rather than reduce one’s belief in human dignity? Explain.

7. Waiting for Godot was immediately understood and appreciated by the inmates in a Florida prison where it was first performed. Why do you suppose this is? How do Time and Waiting play major roles in Waiting for Godot? How is the problem of human existence looked upon in the play?

SHORT RESPONSE QUESTIONS ON CAMUS’S ESSAY, “THE MYTH OF SISYPHUS”:

Directions: Answer each of the questions below in 1 paragraph. (A paragraph is 8-12 sentences)

1. You may find it necessary to reread this essay carefully two or three times to follow Camus’s argument. Sisyphus he sees as in some ways like all the rest of us, engaged in a repeated cycle of labor that is ultimately pointless and futile. What portion of the cycle interests the author most? Why?

2. Camus suggests that only those people who are conscious of the pattern of their lives—who can at times stand off from that pattern and see it for what it is—can be thought of as either tragic or happy. Most of us live the bulk of our lives day by day, imprisoned in the present, and it is only in those “hours of consciousness” that we rise above ourselves and become superior to our fate. What connection does the author find between happiness and an awareness of absurdity? Why does he feel that Sisyphus must be happy?

3. Though in some ways Sisyphus is like the rest of us, he is quite different from most of us, too. On earth, Sisyphus was a hero, a man of great dimensions. What acts and attributes of his that support his heroism does the essay mention? Why was Sisyphus condemned to eternal punishment?

4. Many of us avert our gaze from what we make of life, preferring to live unquestioningly from day to day. The great man, however, does not. He is not afraid to confront the meaning of his life, even though the confrontation may be painful and filled with sorrow. But it may be joyful too. “The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory.” (231) Explain your understanding of that remark in the context in which it appears.

The Myth of Sisyphus https://webmail.woodbridge.k12.nj.us/owa/attachment.ashx? attach=1&id=RgAAAAAs5qK0WgrhRKDw5UY%2fMrVZBwDjhFsqv6INTZe %2f7Eom3Y6dAAAACE6hAADjhFsqv6INTZe %2f7Eom3Y6dAAACwKVWAAAJ&attid0=BAAAAAAA&attcnt=1 by Albert Camus

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.

If one believes Homer, Sisyphus was the wisest and most prudent of mortals. According to another tradition, however, he was disposed to practice the profession of highwayman. I see no contradiction in this. Opinions differ as to the reasons why he became the futile laborer of the underworld. To begin with, he is accused of a certain levity in regard to the gods. He stole their secrets. Egina, the daughter of Esopus, was carried off by Jupiter. The father was shocked by that disappearance and complained to Sisyphus. He, who knew of the abduction, offered to tell about it on condition that Esopus would give water to the citadel of Corinth. To the celestial thunderbolts he preferred the benediction of water. He was punished for this in the underworld. Homer tells us also that Sisyphus had put Death in chains. Pluto could not endure the sight of his deserted, silent empire. He dispatched the god of war, who liberated Death from the hands of her conqueror.

It is said that Sisyphus, being near to death, rashly wanted to test his wife's love. He ordered her to cast his unburied body into the middle of the public square. Sisyphus woke up in the underworld. And there, annoyed by an obedience so contrary to human love, he obtained from Pluto permission to return to earth in order to chastise his wife. But when he had seen again the face of this world, enjoyed water and sun, warm stones and the sea, he no longer wanted to go back to the infernal darkness. Recalls, signs of anger, warnings were of no avail. Many years more he lived facing the curve of the gulf, the sparkling sea, and the smiles of earth. A decree of the gods was necessary. Mercury came and seized the impudent man by the collar and, snatching him from his joys, lead him forcibly back to the underworld, where his rock was ready for him.

You have already grasped that Sisyphus is the absurd hero. He is, as much through his passions as through his torture. His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing. This is the price that must be paid for the passions of this earth. Nothing is told us about Sisyphus in the underworld. Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. As for this myth, one sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to roll it, and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees the face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earth-clotted hands. At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward tlower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain.

It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock. If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works everyday in his life at the same tasks, and his fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn.

If the descent is thus sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy. This word is not too much. Again I fancy Sisyphus returning toward his rock, and the sorrow was in the beginning. When the images of earth cling too tightly to memory, when the call of happiness becomes too insistent, it happens that melancholy arises in man's heart: this is the rock's victory, this is the rock itself. The boundless grief is too heavy to bear. These are our nights of Gethsemane. But crushing truths perish from being acknowledged. Thus, Edipus at the outset obeys fate without knowing it. But from the moment he knows, his tragedy begins. Yet at the same moment, blind and desperate, he realizes that the only bond linking him to the world is the cool hand of a girl. Then a tremendous remark rings out: "Despite so many ordeals, my advanced age and the nobility of my soul make me conclude that all is well." Sophocles' Edipus, like Dostoevsky's Kirilov, thus gives the recipe for the absurd victory. Ancient wisdom confirms modern heroism.

One does not discover the absurd without being tempted to write a manual of happiness. "What!---by such narrow ways--?" There is but one world, however. Happiness and the absurd are two sons of the same earth. They are inseparable. It would be a mistake to say that happiness necessarily springs from the absurd. Discovery. It happens as well that the felling of the absurd springs from happiness. "I conclude that all is well," says Edipus, and that remark is sacred. It echoes in the wild and limited universe of man. It teaches that all is not, has not been, exhausted. It drives out of this world a god who had come into it with dissatisfaction and a preference for futile suffering. It makes of fate a human matter, which must be settled among men.

All Sisyphus' silent joy is contained therein. His fate belongs to him. His rock is a thing. Likewise, the absurd man, when he contemplates his torment, silences all the idols. In the universe suddenly restored to its silence, the myriad wondering little voices of the earth rise up. Unconscious, secret calls, invitations from all the faces, they are the necessary reverse and price of victory. There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night. The absurd man says yes and his efforts will henceforth be unceasing. If there is a personal fate, there is no higher destiny, or at least there is, but one which he concludes is inevitable and despicable. For the rest, he knows himself to be the master of his days. At that subtle moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning toward his rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated actions which become his fate, created by him, combined under his memory's eye and soon sealed by his death. Thus, convinced of the wholly human origin of all that is human, a blind man eager to see who knows that the night has no end, he is still on the go. The rock is still rolling.

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.