Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Gas & Development

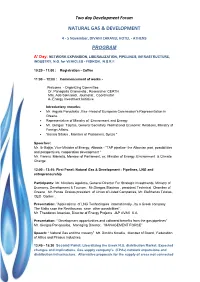

Two day Development Forum NATURAL GAS & DEVELOPMENT 4 - 5 November, DIVANI CARAVEL HOTEL - ATHENS (DRAFT PROGRAM) A’ Day: NETWORK EXPANSION, LIBERALIZATION, PIPELINES, INFRASTRUCTURE ELECTRICITY PRODUCTION, INDUSTRY, N.G. for VEHICLES - FISIKON, N.S.R.F. 11:15 - 12:00: Commencement of works - introductory presentations Greetings - Organizing Committee Mr. Panos Carvounis,Head of European Commission’s Representation in Greece. Mr. Panos Scourletis, Minister of Environment and Energy Mr. Yiannis Tsironis, Deputy Minister of Environment & Energy. Mr. Giorgos Tsipras, General Secretary International Economic Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Greetings of Foreign Embassies 12:00 - 13:45: First Panel: Natural Gas & Development Speech: Mr. Yiannis Maniatis, Member of Parliament, ex. Minister of Energy, Environment & Climate Change. Part One Participants: Representative DEPA management, representative of DESFA management, representative of PPC , Mr. Dimitris Mathios , president of Federation of Attica and Piraeus Industries., Mr. Panos Drakos president of Union of Listed Companies . Part Two: Pipelines, LNG and entrepreneurship Speech: Μr. Illir Bejtja, Vice-Μinister of Environment and Energy, Albania TΑP pipeline- The Albanian part. Possibilities and Perspectives Vice-Μinister of Albania Participants: ASPROFOS ( TAP works Direction) , DEPA works Direction, Mr. Giorgos Pavlidis , Head of Eastern Macedonia – Thraki Region, Mr. Giorgos Stasinos,President of Technical Chamber of Greece, representative Albanian Ministry of Energy & Industry. Programmed Intervention : Mr. Eleftherios Tziolas , CEO Contec, Mr. Giorgos Panopoulos , Managing Director, M for Safety S.A. (Panel not completed yet) 13:45 - 15:30 Second Panel: Liberalizing the Greek N.G. distribution Market. Expected changes and implications. Gas supply company’s (EPAs) network expansions and distribution infrastructure. Alternative proposals for the supply of areas not connected to the main network and areas that are not covered yet by the existing networks. -

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, and ETHNO-REGIONALISM in PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING by IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in Parti

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, AND ETHNO-REGIONALISM IN PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING BY IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donna A. Buchanan, Chair Professor Emeritus Thomas Turino Professor Gabriel Solis Professor Maria Todorova ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the multilayered connections between music, emotionality, social and cultural belonging, collective memory, and identity discourse. The ethnographic case study for the examination of all these relations and aspects is the Pontic muhabeti or parakathi. Parakathi refers to a practice of socialization and music making that is designated insider Pontic Greek. It concerns primarily Pontic Greeks or Pontians, the descendants of the 1922 refugees from Black Sea Turkey (Gr. Pontos), and their identity discourse of ethno-regionalism. Parakathi references nightlong sessions of friendly socialization, social drinking, and dialogical participatory singing that take place informally in coffee houses, taverns, and households. Parakathi performances are reputed for their strong Pontic aesthetics, traditional character, rich and aesthetically refined repertoire, and intense emotionality. Singing in parakathi performances emerges spontaneously from verbal socialization and emotional saturation. Singing is described as a confessional expression of deeply personal feelings -

IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology 475

IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology 475 Editor-in-Chief Kai Rannenberg, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany Editorial Board Foundation of Computer Science Jacques Sakarovitch, Télécom ParisTech, France Software: Theory and Practice Michael Goedicke, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany Education Arthur Tatnall, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia Information Technology Applications Erich J. Neuhold, University of Vienna, Austria Communication Systems Aiko Pras, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands System Modeling and Optimization Fredi Tröltzsch, TU Berlin, Germany Information Systems Jan Pries-Heje, Roskilde University, Denmark ICT and Society Diane Whitehouse, The Castlegate Consultancy, Malton, UK Computer Systems Technology Ricardo Reis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil Security and Privacy Protection in Information Processing Systems Stephen Furnell, Plymouth University, UK Artificial Intelligence Ulrich Furbach, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany Human-Computer Interaction Jan Gulliksen, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden Entertainment Computing Matthias Rauterberg, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands IFIP – The International Federation for Information Processing IFIP was founded in 1960 under the auspices of UNESCO, following the first World Computer Congress held in Paris the previous year. A federation for societies working in information processing, IFIP’s aim is two-fold: to support information processing in the countries of its members and to encourage technology transfer to developing na- tions. As its mission statement clearly states: IFIP is the global non-profit federation of societies of ICT professionals that aims at achieving a worldwide professional and socially responsible development and application of information and communication technologies. IFIP is a non-profit-making organization, run almost solely by 2500 volunteers. -

Reflecting on the Kapodistrian Orphanage and Aegina Prison

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Objects as Portals Material Engagement and the Arts as a Catalyst for Social Change. Reflecting on the Kapodistrian Orphanage and Aegina Prison Vlachaki, Eleni Award date: 2019 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Objects as Portals: Material Engagement and the Arts as a Catalyst for Social Change Reflecting on the Kapodistrian Orphanage and Aegina Prison Elika (Eleni) Vlachaki DOJ College of Art & Design University of Dundee A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 i Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................. i Illustrations ...................................................................................................................... -

Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions

01/07/2014 14:20 MULTIMEDIA CPMR France Belgique CPMR EDITION @CPMR_Europe Régie et Réalisation : et Réalisation Régie Phone: +32 2 612 17 00 Phone: +32 2 612 17 Phone: + 33 2 99 35 40 50 Phone: + 33 2 99 35 40 50 Tél. 00 33 (0)468 669 475 Email: [email protected] Fax. 00 33 (0)468 669 333 Mél : [email protected] 6, rue St Martin - 35700 Rennes 6, rue St Martin - 35700 www.crpm.org www.cpmr.org www.cpmr.org www.crpm.org 66028 PERPIGNAN Cedex CRPM FR NCE Rond-Point Schuman,14 - 1040 Bruxelles Rond-Point http://corporate.brittany-ferries.com Un réseau d’autoroutes de la mer Atlantique au service de l’Arc 70 avenue Alfred Kastler Alfred - CS 90014 70 avenue Conference of Conference Peripheral Maritime Regions www.cpmr.org BF AP Instit 40x90.indd 1 Bosna i Hercegovina (BA) United Kingdom (UK) 1-Unsko-sanski 1-Poole 2-Posavski 2-Bournemouth 3-Tuzlanski 3-Southampton 4-Zeničko-dobojski 4-Portsmouth 5-Bosansko-podrinjski 5-Brighton and Hove 6-Srednjobosanski 6-Medway 7-Hercegovačko-neretvanski 7-Thurrock 8-Zapadnohercegovački 8-Southend-on-Sea 9-Sarajevo 9-Greater London 10-Kanton br. 10 10-Bracknell Forest 11-Windsor and Maidenhead 12-Wokingham Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft (CH) 13-Reading Confédération suisse 14-West Berkshire Confédération Svizzera 15-Swindon Conferaziun svira 16-Bath and North East Somerset 1-Zürich 17-North Somerset 2-Bern 18-City of Bristol 3-Luzern 19-South Gloucestershire 4-Uri 20-Gloucestershire 5-Schwyz 21-Oxfordshire 6-Obwalden 22-Buckinghamshire 7-Nidwalden 23-Hertfordshire 8-Glarus 24-Lutton 9-Zug 25-Central Bedfordshire 10-Freiburg 26-Milton Keynes 11-Solothurn 27-Bedford 12-Basel-Stadt 28-Northamptonshire 13-Basel-Landschaft 29-Cambridgeshire 14-Schaffhausen 30-Warwickshire 15-Appenzell Ausserrhoden 31-Worcestershire 16-St. -

George Pavlidis

George P. Pavlidis Curriculum Vitae Name: George Pavlidis Date of birth: March 6, 1970 Place of birth: Kavala, Greece Nationality: Greek Occupation: Research Director Athena - Research and Innovation Center in Information, Communication and Knowledge Technologies ILSP - Institute for Language and Speech Processing Expertise: Inage processing and multimedia applications in culture and education Postal address: University Campus at Kimmeria, PO BOX 159, 67100, Xanthi, Greece Telephone: +30-2541078787 Fax: +30 2541063656 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Languages: English (fluent), German (intermediate), French (beginner) Military Service 22/3/1999 – 22/2/2001 Web references: ORCID http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9909-1584 ResearchID http://www.researcherid.com/rid/L-5050-2013 Google Scholar http://goo.gl/yQ2cwj Scopus http://goo.gl/S8Mv3U LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=4371928 ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/profile/George_Pavlidis2 Academia.edu https://athena-innovation.academia.edu/GeorgePavlidis Personal pages http://georgepavlides.info, http://goo.gl/tPIoME 1 Table of Contents 1 DEGREES ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 LIFELONG LEARNING ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2 ACADEMIC, RESEARCH AND INNOVATION PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE ........................... 3 2.1 CURRENT POSITIONS -

Final Programme

WHO European Healthy Cities Networks Divani Caravel Hotel FINAL PROGRAMME Health and the City: Urban Living in the Twenty first Century Visions and best solutions for cities committed to health and well-being Marking 25 years of the Healthy Cities movement www.healthycities2014.org HELLENIC HEALTHY CITIES NETWORK International Healthy Cities Conference “Health and the City: Urban living in the 21st Century” Divani Caravel Hotel Athens, Greece 22-25 October 2014 CONTENTS 04 Forewords Welcome message from the Mayor of Amaroussion Welcome message from WHO 06 Programme overview 14 Floor plans Divani Caravel Hotel 16 General information 20 Programme Wednesday, 22 october Thursday, 23 october Friday, 24 October Saturday, 25 october 40 Site visits 41 Social programme 42 Organization 45 Acknowledgements *Last update: 20.10.2014 Welcome message from the Mayor of Amaroussion George Patoulis Dear Friends from all over the world, It is a great honour and privilege for the Municipality of Amaroussion and the Hellenic Healthy Cities Network to have been appointed to host the International Healthy Cities Conference “Health and the City: Urban living in the 21st Century”, which will be organized in Athens, Greece, on 22-25 October 2014. This year’s international conference marks 25 years of implementation of the WHO Healthy Cities programme in the European region and the launch of the sixth 5-year phase, 2014-2018. It also marks the implementation of the new WHO agenda, “Health 2020”. In the course of time, the WHO Healthy Cities Network has been a movement of inspiration, innovation, exchange of information and know-how, and has brought the issue of health and quality of life to the top of the cities’ agenda. -

George P. Pavlidis Curriculum Vitae

George P. Pavlidis Curriculum Vitae version: June 5, 2020 Date of birth March 6, 1970 Place of birth Kavala, Greece Nationality Greek Occupation Research Director Athena - Research and Innovation Centre in Information, Communica- tion and Knowledge Technologies ILSP - Institute for Language and Speech Processing Expertise: Image processing and multimedia applications in culture and education Postal address University Campus at Kimmeria PO BOX 159, GR-67100, Xanthi, Greece Telephone +30-2541078787 Fax +30-2541063656 E-mail [email protected], [email protected] Languages English (fluent), German (intermediate), French (beginner) Military Service 22/3/1999 { 22/2/2001 Web references Google Scholar: http://goo.gl/yQ2cwj Scopus: http://goo.gl/S8Mv3U ResearchID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/L-5050-2013 ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9909-1584 Personal webpages http://georgepavlides.info, https://bit.ly/2XVmx5d 1 Contents 1 Education 3 1.1 Degrees . 3 1.2 Lifelong learning & development . 3 2 Academic, research and innovation professional experience 3 2.1 Current positions . 3 2.2 Past positions . 4 3 Scientific and research activity 5 3.1 Honours, distinctions and awards . 5 3.2 Distinguished lectures . 5 3.3 Contribution to the scientific community . 6 4 Teaching 11 4.1 Independent teaching . 11 4.2 Laboratory organization and teaching assistantship . 12 4.3 PhD theses supervision . 12 4.4 Masters theses supervision . 12 4.5 Graduate theses supervision . 13 4.6 Academic committees . 14 4.7 Supervision of internships . 16 4.8 Seminar courses & talks . 16 5 Administration activities 17 5.1 Associations and organizations . 17 5.2 Committees . 18 6 Research and development projects 19 6.1 European projects . -

IFIP AICT 437 Lazaros Iliadis Ilias Maglogiannis Harris Papadopoulos Spyros Sioutas Christos Makris (Eds.)

IFIP AICT 437 Lazaros Iliadis Ilias Maglogiannis Harris Papadopoulos Spyros Sioutas Christos Makris (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations AIAI 2014 Workshops: CoPA, MHDW, IIVC, and MT4BD Rhodes, Greece, September 19–21, 2014 Proceedings 123 IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology 437 Editor-in-Chief A. Joe Turner, Seneca, SC, USA Editorial Board Foundations of Computer Science Jacques Sakarovitch, Télécom ParisTech, France Software: Theory and Practice Michael Goedicke, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany Education Arthur Tatnall, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia Information Technology Applications Erich J. Neuhold, University of Vienna, Austria Communication Systems Aiko Pras, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands System Modeling and Optimization Fredi Tröltzsch, TU Berlin, Germany Information Systems Jan Pries-Heje, Roskilde University, Denmark ICT and Society Diane Whitehouse, The Castlegate Consultancy, Malton, UK Computer Systems Technology Ricardo Reis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil Security and Privacy Protection in Information Processing Systems Yuko Murayama, Iwate Prefectural University, Japan Artificial Intelligence Tharam Dillon, Curtin University, Bentley, Australia Human-Computer Interaction Jan Gulliksen, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden Entertainment Computing Matthias Rauterberg, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands IFIP – The International Federation for Information Processing IFIP was founded -

Natural Gas & Development

Two day Development Forum NATURAL GAS & DEVELOPMENT 4 - 5 November, DIVANI CARAVEL HOTEL - ATHENS PROGRAM A’ Day: NETWORK EXPANSION, LIBERALIZATION, PIPELINES, INFRASTRUCTURE, INDUSTRY, N.G. for VEHICLES - FISIKON, N.S.R.F. 10:20 - 11:00 : Registration - Coffee 11:00 – 12:00 : Commencement of works - Welcome - Organizing Committee Dr. Panagiotis Grammelis , Researcher CERTH Mrs. Ada Seimanidi, Journalist , Coordinator A- Energy Investment Initiative Introductory remarks: Mr. Argyris Peroulakis ,Vice -Head of European Commission’s Representation in Greece. Representative of Ministry of Environment and Energy Mr. Giorgos Tsipras, General Secretary International Economic Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Yiannis Sifakis , Member of Parliament, Syriza * Speeches: Μr. Ilir Bejtja, Vice-Μinister of Energy, Albania - “TΑP pipeline- the Albanian part, possibilities and perspectives, cooperation development “ Mr. Yiannis Maniatis, Member of Parliament, ex. Minister of Energy, Environment & Climate Change. 12:00 - 13:45: First Panel: Natural Gas & Development - Pipelines, LNG and entrepreneurship Participants: Mr. Nikolaos Agaliotis, General Director For Strategic Investments, Ministry of Economy, Development & Tourism, Mr.Giorgos Stasinos , president Technical Chamber of Greece, Mr. Panos Drakos president of Union of Listed Companies, Mr. Eleftherios Tziolas , CEO Contec . Presentation: “Applications of LNG Technologies internationally , by a Greek company The Malta case the Revithoussa case other possibilities”. Mr. Theodoros Arseniou, Director of Energy Projects J&P AVAX S.A. Presentation: “ Development opportunities and collateral benefits from the gas pipelines” Mr. Giorgos Panopoulos, Managing Director, “MANAGEMENT FORCE” Speech: “ Natural Gas and the Industry” Mr. Dimitris Kolaitis, Member of Board , Federation of Attica and Piraeus Industries. 13:45 - 15:30 Second Panel: Liberalizing the Greek N.G. distribution Market. -

The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities Chamber of Regions

The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities Chamber of Regions 15th PLENARY SESSION CPR(15)2REP 6 May 2008 Regional democracy in Greece Jean-Claude Van Cauwenberghe, Belgium (R, SOC) Explanatory Memorandum Institutional Committee Summary: The Explanatory Memorandum analyzes the functioning of prefectural level of territorial self-government in Greece. The Prefectures constitute the regional tier of territorial organisation in Greece (regions without legislative power) according to the criteria of the Congress. These territorial entities, the members of which are democratically elected, hold competences and financial resources for carrying out their functions. Currently the prefectural tier is undergoing a major reform aimed at further democratisation and territorial reorganisation. In its first part the Explanatory Memorandum explains in detail the political functioning and management of these administrative entities, the role of the Secretary General of the Region (“Periferiaie”) vis-à-vis the local authorities, the financial system of Prefectures, their role in the management of European structural funds, the conditions of service of the staff of Prefectures, etc. The major characteristics of the ongoing reform, legislative and political developments related to this reform are also examined. In its final part, the Explanatory Memorandum contains suggestions particularly for remedying the identified problems, pursuing the ongoing reform, reinforcing the democratic principles of territorial self-government and giving follow-up to the initiatives of territorial reorganisation aimed at better governance. R : Chamber of Regions / L : Chamber of Local Authorities ILDG : Independent and Liberal Democrat Group of the Congress EPP/CD : Group European People’s Party – Christian Democrats of the Congress SOC : Socialist Group of the Congress NR : Member not belonging to a Political Group of the Congress I. -

Bi-Annual Report 2013-2014

South-East European Research Centre. Bi-annual Report 2013 - 2014. Table of Contents 1 RESEARCH @ SEERC ........................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Externally funded research projects update .................................................... 3 1.1.1 New Awards ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1.2 Ongoing Research Projects (as of the end of December 2014) ........... 5 1.1.3 Completed Research Projects in 2013-2014 ................................................. 6 1.2 Other Research Activities .......................................................................................... 8 1.2.1 Research Submissions ............................................................................................ 8 1.2.2 Publications ............................................................................................................. 8 2 THE DOCTORAL PROGRAMME ........................................................................................ 8 2.1 Viva examinations .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Confirmation Review Process ................................................................................. 9 2.3 Call for Doctoral Applications 2013-2014 & 2014-2015 .................................. 11 New Admissions .........................................................................................................................