TMA 04 - 25/9/97 J.P.BIRCHALL PO194869

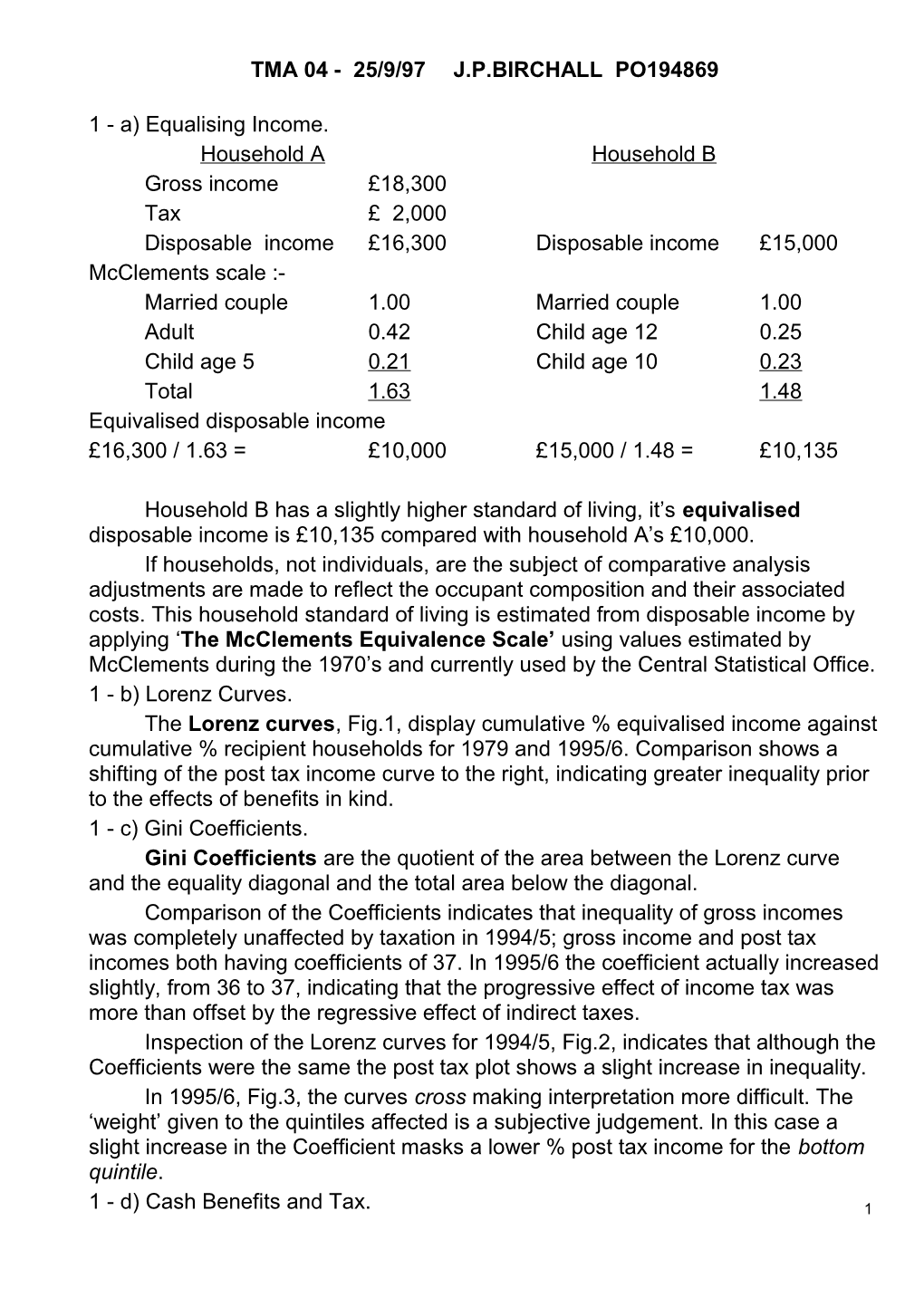

1 - a) Equalising Income. Household A Household B Gross income £18,300 Tax £ 2,000 Disposable income £16,300 Disposable income £15,000 McClements scale :- Married couple 1.00 Married couple 1.00 Adult 0.42 Child age 12 0.25 Child age 5 0.21 Child age 10 0.23 Total 1.63 1.48 Equivalised disposable income £16,300 / 1.63 = £10,000 £15,000 / 1.48 = £10,135

Household B has a slightly higher standard of living, it’s equivalised disposable income is £10,135 compared with household A’s £10,000. If households, not individuals, are the subject of comparative analysis adjustments are made to reflect the occupant composition and their associated costs. This household standard of living is estimated from disposable income by applying ‘The McClements Equivalence Scale’ using values estimated by McClements during the 1970’s and currently used by the Central Statistical Office. 1 - b) Lorenz Curves. The Lorenz curves, Fig.1, display cumulative % equivalised income against cumulative % recipient households for 1979 and 1995/6. Comparison shows a shifting of the post tax income curve to the right, indicating greater inequality prior to the effects of benefits in kind. 1 - c) Gini Coefficients. Gini Coefficients are the quotient of the area between the Lorenz curve and the equality diagonal and the total area below the diagonal. Comparison of the Coefficients indicates that inequality of gross incomes was completely unaffected by taxation in 1994/5; gross income and post tax incomes both having coefficients of 37. In 1995/6 the coefficient actually increased slightly, from 36 to 37, indicating that the progressive effect of income tax was more than offset by the regressive effect of indirect taxes. Inspection of the Lorenz curves for 1994/5, Fig.2, indicates that although the Coefficients were the same the post tax plot shows a slight increase in inequality. In 1995/6, Fig.3, the curves cross making interpretation more difficult. The ‘weight’ given to the quintiles affected is a subjective judgement. In this case a slight increase in the Coefficient masks a lower % post tax income for the bottom quintile.

1 - d) Cash Benefits and Tax. 1 TMA 04 - 25/9/97 J.P.BIRCHALL PO194869 The distribution of post tax incomes measured by Gini Coefficients moved from 29 in 1977 to 37 in 1995/6, a change of 8 points. However, the corresponding change in original income was from 43 to 52, 9 points, indicating that the increase in inequality during the period resulted from movements in original incomes and not changes in cash benefits and tax. The effects of the benefits and tax were similar in both periods. In 1977 cash benefits shifted the Gini Coefficient 14 points and in 1995/6, 16 points, indicating benefits reduced inequality slightly more in 1995/6. However, in both periods the effect of taxation was broadly neutral. Thus, Government action on the supply side may have had a significant effect on original earnings (reflecting higher unemployment from a loss of unskilled jobs and higher remuneration for skills?) but there was little change in the effect of cash benefits and tax. 1 - e) Income Redistribution. Conceptual difficulties surround the definition of income and poverty. The Haig-Simons opportunity set includes non money income in a definition of full income. It has also been suggested that a redistributive issue is income earning potential. Further problems are associated with line drawing between absolute and relative poverty, the depth (poverty gap) and the duration (lifetime income?) of poverty, and also the income unit concerned, households or individuals, with the complication of equivalising incomes? Measurement of income presents difficulties of distinguishing between income and capital, quantifying income in kind and imputed income from durable wealth. There is also the thorny issue of honesty and the black economy. What Frank Field has called the problem of effort, saving and honesty [1]. Measurement of benefits is even more prone to subjective judgements. CSO uses input costs to indicate benefit. Le Grand and others attempted further analysis but the issue remains highly controversial because of different personal perspectives and ‘the recurring theme in debate between contingent and means tested benefits’ [2]. Separating tax and benefit is problematic raising the intractable issues of tax incidence and means tested poverty traps. Furthermore some 50% of expenditure/revenue is not allocated to individual households, including major funds associated with defence, law and order and corporation tax. These complexity and interaction issues cast doubt on the usefulness of income redistribution analysis, ‘the poor are a more complex group than once perceived’ [3]. A better understanding of the issue may come from education and is it indicative of the problem that New Labour’s manifesto has three priorities, education, education and education and no mention of income redistribution?[4].

2 The National Health Service. 2 TMA 04 - 25/9/97 J.P.BIRCHALL PO194869 In 1944 an equity objective was established to promote health amongst the poor. Subsequently, although treatment and care were available free at the point of demand, standardised mortality rates (age adjusted life expectancy as a % of the national average) of the poor remained low. The empirical evidence of Black indicated that health was probably determined by cultural, social and lifestyle factors. In these circumstance ‘the whole of the GNP could readily be spent on the NHS’ without solving the problem. The issue of efficiency emerged as a consequence. Although the proportion of GNP spent on the NHS remains largely a ‘macro’ political decision, the ‘micro’ decisions on how best to spend scare resources have become the subject of economic analysis. Note that the proportion of GNP and whether it is spent in the public or private sectors also lends itself to economic analysis through the theory of public choice [5]. Free access to valuable resources can explain excess demand. Demand exacerbated by demographic bulges, rampant new technology, low productivity in service sectors and expectations of improved treatment and care as new threats from environmental hazards, smoking, obesity, AIDS and drugs are perceived. Summed up by Alan Williams as ‘high tech intervention in the vain pursuit of immortality’ [6], this demand must be rationed in some way and the efficiency issue of maximising the value of scare resources, or allocative and productive efficiency, becomes a priority. Economic analysis is impeded by measurement difficulties. The cost of the NHS whether it be expressed in cash, real or volume terms says nothing about the quantity or quality of outputs. To investigate outputs several options are available :- - cost effectiveness. Although annual NHS expenditure is £34bn there is no tradition of activity costing and cost effectiveness analysis requires data on direct and indirect costs, costs of delays and opportunities foregone, and including, perhaps, the cost of pain and suffering! However, a bigger problem is measuring benefits which are seldom the same as physical outputs. - cost utility. Cost utility analysis attempts to contribute by developing benefit measures. Rosser standardised benefits and their duration as quality adjusted life years (QALY). Quality of life was assessed in terms of disability and distress by interviewing respondents The QALY approach to human life has been criticised as immoral, ‘national values stress the equality of citizens in their relation to the institutions of state’[6]. Others accept that choices have to be made but prefer political decisions, and don’t accept QALY as an aid to decision making, ‘there is no reason to expect that maximising the production of QALY will lead to the same resource distribution as 3 TMA 04 - 25/9/97 J.P.BIRCHALL PO194869 informed user wishes’ [6]. For some, QALY implies an unacceptable bias against the elderly. A final criticism of QALY suggests subjective judgements based on inadequate research. However, it is hard to escape the reality of scarce resources where equity and efficiency become inseparable, and choices have to be made one way or the other. - cost benefit Cost benefit analysis is another approach which puts money values on benefits, but this only intensifies the emotional criticisms. In response to these difficulties the concept of internal markets, or quasi markets, was developed by Alain Enthoven in 1985. The idea was to retain the equity of free access whist introducing buyers and sellers so that the process of competition produced allocative and productive efficiency. Economic analysis indicates that choosing between competing alternatives will produce Pareto efficiency. Benefits will be reflected in prices which will reflect costs and costs will be minimised through the removal of X-inefficiency by differential survival. Establishing consumer prices to reflect informed user wishes is not easy and in their absence QALY or some other proxy may still be involved in benefit judgements. However, it is not only lack of pricing data that is the problem, markets are inefficient where public goods, monopoly, externalities and information shortages are involved. Furthermore there are particular problems in the health service with established beliefs. Equity is not perceived as a minimum standard but as equality. Although equality is ephemeral - costs in terms of public expenditure per head? or individual circumstances or need? or outcome as equality of health? - differences in the standard of treatment and care, or a multi-tier service, remain anathema. But the consequences of competitive markets are inevitable. Innovation, scale economies, specialisation, investment levels, all produce differences; some will be better than others, leading to inequality. The controversy over GP fundholding illustrates the difficulty. Even with identical inputs different choices in the practices will produce performance differences and progress follows from perceiving these differences between the best and the worst. A recent editorial in the Financial Times confirms ‘the challenge now facing the NHS is how to spread best practice’ [7]. Analysis suggests the worst performers should be replaced by the best, a process of differential survival, or bankruptcy/take-over? The asymmetry of medical knowledge is a further problem, GP’s, as buying agents, do not necessarily produce optimal results. In spite of Hippocratic oaths and the belief in the benevolence of the medical profession, the assumption of motivation ‘in the public interest’ is rash. Supplier induced demand is a problem and decision making by clinicians is jealously guarded against inroads from

4 TMA 04 - 25/9/97 J.P.BIRCHALL PO194869 managers and politicians. But again economic analysis can help understanding, the theory of public choice [8] applies to medics as well as politicians! Many obstacles can be overcome if patients are free to change GP’s and GP’s free to choose hospitals. But the process remains stymied if costs are unavailable and there remains a reluctance to cost. The internal market only addresses efficiency and quality issues it says nothing about funding. Nevertheless economic analysis of quasi markets is producing a consensus reflected in a recent OECD report which concludes that ‘despite starting from very different health systems all countries are converging on the same solution to escalating costs; managed markets’ [9]. The Oregon policy initiative [10] is another recent controversy illustrating the relevance of economic analysis. If rationing is not by price a possible alternative involves explicit rationing by hierarchy based on category ranking of treatments with a cut off point based on funding available. Categories, agreed by consumer research, would determine rationing not secretive clinicians and bureaucrats in the NHS behind closed doors. Economic analysis cannot provide answers, but it can explain the patterns of policy outcomes given the initial circumstances.

[1] Making welfare work – Frank Field – Institute of Community Studies 1995. [2] The British tax system – Kay and King – 1990. [3] Statistics hide a complex picture –Nicholas Timmins – Financial Times 16/4/96. [4] Britain will be better with New Labour - Labour Party Manifesto – 1997. [5] How to pay for health care, public and private alternatives – IEA – 1997. [6] The rationing debate – Alan Williams / Grimley Evans – British Medical Journal – March 1997. [7] GP fundholding – Editorial – Financial Times – 1996. [8] The calculus of consent – Buchanan & Tullock – Ann Arbour - 1965. [9] The Reform of Health Care – OECD – 1993. [10] Candour at last on health care - Michael Prowse – Financial Times 22/6/92.

5