Paul Gauguin: Where Do We Come From? What Art We? Where Are We Going? (1897-98)

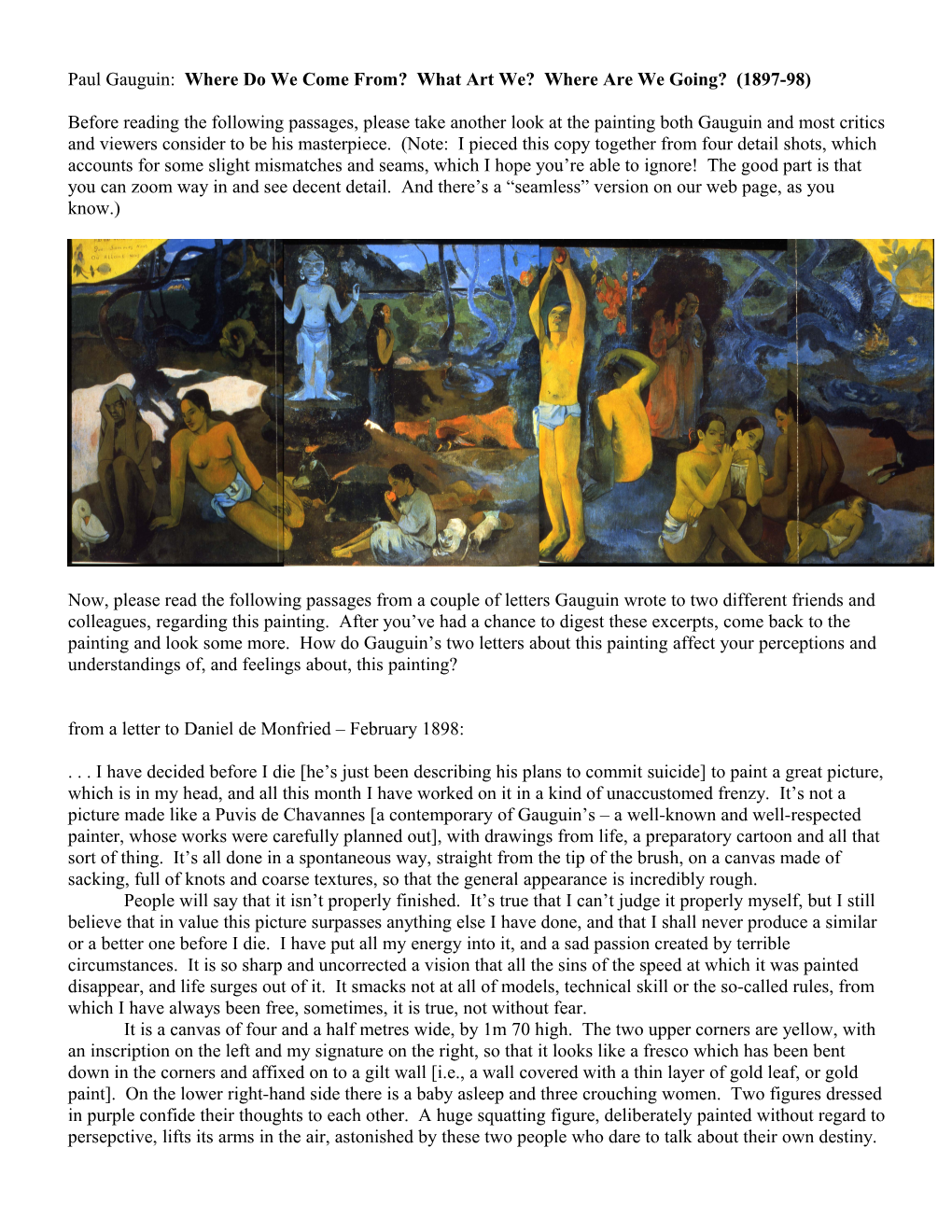

Before reading the following passages, please take another look at the painting both Gauguin and most critics and viewers consider to be his masterpiece. (Note: I pieced this copy together from four detail shots, which accounts for some slight mismatches and seams, which I hope you’re able to ignore! The good part is that you can zoom way in and see decent detail. And there’s a “seamless” version on our web page, as you know.)

Now, please read the following passages from a couple of letters Gauguin wrote to two different friends and colleagues, regarding this painting. After you’ve had a chance to digest these excerpts, come back to the painting and look some more. How do Gauguin’s two letters about this painting affect your perceptions and understandings of, and feelings about, this painting? from a letter to Daniel de Monfried – February 1898:

. . . I have decided before I die [he’s just been describing his plans to commit suicide] to paint a great picture, which is in my head, and all this month I have worked on it in a kind of unaccustomed frenzy. It’s not a picture made like a Puvis de Chavannes [a contemporary of Gauguin’s – a well-known and well-respected painter, whose works were carefully planned out], with drawings from life, a preparatory cartoon and all that sort of thing. It’s all done in a spontaneous way, straight from the tip of the brush, on a canvas made of sacking, full of knots and coarse textures, so that the general appearance is incredibly rough. People will say that it isn’t properly finished. It’s true that I can’t judge it properly myself, but I still believe that in value this picture surpasses anything else I have done, and that I shall never produce a similar or a better one before I die. I have put all my energy into it, and a sad passion created by terrible circumstances. It is so sharp and uncorrected a vision that all the sins of the speed at which it was painted disappear, and life surges out of it. It smacks not at all of models, technical skill or the so-called rules, from which I have always been free, sometimes, it is true, not without fear. It is a canvas of four and a half metres wide, by 1m 70 high. The two upper corners are yellow, with an inscription on the left and my signature on the right, so that it looks like a fresco which has been bent down in the corners and affixed on to a gilt wall [i.e., a wall covered with a thin layer of gold leaf, or gold paint]. On the lower right-hand side there is a baby asleep and three crouching women. Two figures dressed in purple confide their thoughts to each other. A huge squatting figure, deliberately painted without regard to persepctive, lifts its arms in the air, astonished by these two people who dare to talk about their own destiny. A figure in the centre is gathering fruit; there are two cats beside a child; a white goat. The idol, its two arms rhythmically and mysteriously raised, appears to indicate the hereafter. A crouching figure is apparently listening to everything, to resign herself to her thoughts, and to end the story. At her feet, a strange white bird, holding in its claws a lizard, represents the vanity of useless words. The whole scene is set beside a stream under the trees; in the background, the sea and then the mountains of the neighbouring island. Despite certain tonal passages, the general aspect of the work from one end to the other is blue and green, like Veronese [a Venetian painter of the high Renaissance]. All the naked figures stand out in strong orange. If one said to students from the Beaux-Arts [that is, from the “academic” tradition of highly-trained artists who were taught to draw according to what Gauguin somewhat contempuously call “the rules” – using shading, “correct” perspective, etc.]: ‘The painting you must do will represent ‘Where have we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’ what would they do? I have completed a philosophical work on a theme comparable to that of the Gospel [the heart of the New Testament]; I’m sure it’s good. If I have the strength to make a copy, I shall send it to you . . . from a letter to Charles Morice – July 1901:

This great picture of mine is very imperfect in terms of exectuion; it was finished in a month without any preparation or preliminary sketches. I wanted to die and in that state of despair I painted it with a single spurt of energy. I hastened to sign it, and then took a formidable dose of arsenic. Probably it was too much; I endured terrible agony, but not death. My shattered frame, which had to cope with the shock, has been making me suffer. Perhaps in this painting what is lacking in moderation is made up for by something inexplicable to anyone who has not suffered to the bitter end, and who does not know the soul of the painter. . . . Why is it, when faced with a painting, the critic looks for points of comparison with historical ideas and with other painters? Not finding what he thinks ought to be there, he doesn’t understand anything else and is not moved. Feeling first of all, and comprehension follows. Where are we going? Close to the death of an old woman, a strange and stupid bird brings everything to an end. What are we? Daily life. The man of instinct asks himself what all that means. Where do we come from? The source. The child. Communal life. The bird concludes the poem by comparing the inferior being to the intelligent one in the grand order of things propounded in the title. Behind a tree, two sinister figures dressed in robes of a melancholy hue introduce, close to the tree of science, their note of sorrow, caused by science itself, in contrast with the simple human beings in uncontaminated nature, which could be a paradise of human conception leading on to the happiness of living. Other explanatory attributes – familiar symbols – would endow the canvas with a melancholic realism, and the problems propounded could no longer be a poem. In these few words I explain the picture. With your intelligence you need only a few. But as for the general public, why should my brush, freed from all restraint, be obliged to open everybody’s eyes? . . .