CORPORATE TAX CONSIDERATIONS

Accounting Method (¶1515):

Taxpayers that are required to use inventories must use the accrual method of accounting. In general, the accrual method must be used by C Corporations and Partnerships (which includes S Corporations, Limited Liability Companies, etc., that are taxed as partnerships) that do not hold inventories unless the average annual gross receipts for the three previous tax years exceeds $5 million.

Consolidated Tax Returns (¶295):

An affiliated group of corporations can file a consolidated tax return. An affiliated group is defined as corporations connected through stock ownership with a common parent that is an includable corporation provided that the common parent directly owns stock possessing at least 80% of the total voting power of at least one of the other includable corporations and that at least 80% of the stock of all of the other companies is owned by another includable corporation.

Insurance companies, foreign corporations, regulated investment companies, real estate investment trusts (generally), Domestic International Sales Corporations (DISCs) and S Corporations are denied the privilege to consolidate their tax returns.

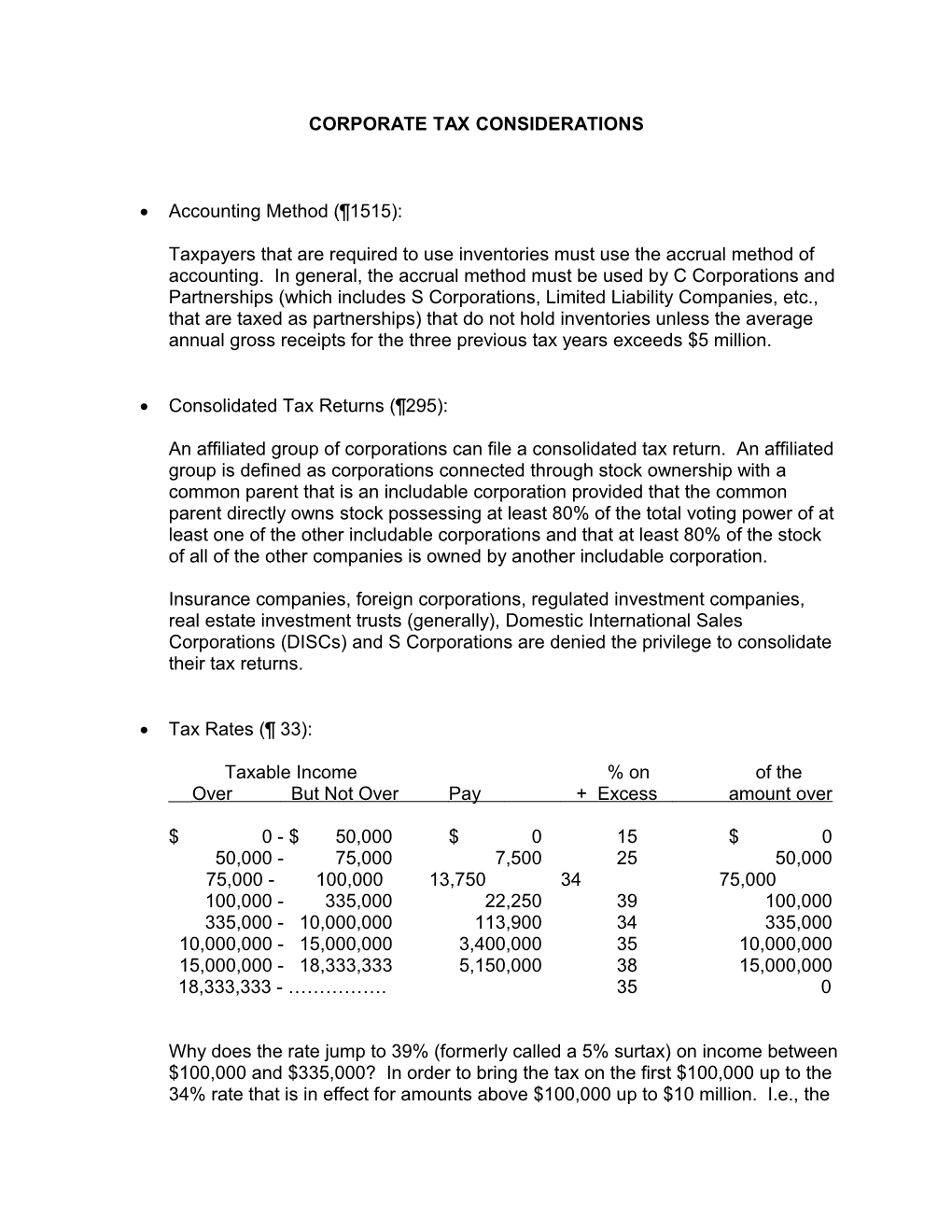

Tax Rates (¶ 33):

Taxable Income % on of the Over But Not Over Pay + Excess amount over

$ 0 - $ 50,000 $ 0 15 $ 0 50,000 - 75,000 7,500 25 50,000 75,000 - 100,000 13,750 34 75,000 100,000 - 335,000 22,250 39 100,000 335,000 - 10,000,000 113,900 34 335,000 10,000,000 - 15,000,000 3,400,000 35 10,000,000 15,000,000 - 18,333,333 5,150,000 38 15,000,000 18,333,333 - ……………. 35 0

Why does the rate jump to 39% (formerly called a 5% surtax) on income between $100,000 and $335,000? In order to bring the tax on the first $100,000 up to the 34% rate that is in effect for amounts above $100,000 up to $10 million. I.e., the average tax rate will rise until it is 34% at $10 million. Similarly, the 38% rate on income between $15 million and $18.33 million is to bring the taxes paid on the first $10 million up to the 35% rate paid on income above $10 million.

Estimated Tax Payments (¶ 225 and ¶227):

Companies that anticipate a tax bill of $500 or more for the year must estimate income tax liability for the year and pay four quarterly estimated tax installments. Installments are due on the 15th day of the fourth, sixth, ninth and twelfth months of the tax year. Thus, for calendar year corporations, estimated taxes are due on April 15, June 15, September 15 and December 15. Companies on a fiscal year basis have estimated tax payments due on the 15th of the fourth, sixth, tenth and twelfth months of the tax year.

Tax deposits in excess of $200,000 must be filed electronically.

Underpayment of taxes is subject to interest for the period of underpayment at the federal short-term rate plus 3% compounded daily (for the first quarter of 2009, the interest rate was 5%; for the second quarter, the third quarter, and the fourth quarter, 4%). Large underpayments (>$100,000) accrue interest at the short-term rate plus 5%. (¶2838)

Underpayment of taxes also incurs a penalty. The penalty is equal to the amount of interest that accrues on the underpayment. (¶2890)

To avoid an underpayment penalty, each installment must equal at least 25% of the lesser of (1) 100 percent of the tax shown on the current year’s tax return or (2) 100 percent of the tax shown on the corporation’s return for the preceding tax year, provided a positive tax liability was shown and the preceding tax year consisted of 12 months (prior year “safe harbor”). The safe harbor provision does not apply to corporations with taxable income of $1 million or more. No additions to tax are applied if the tax liability is less than $500.

Accumulated Earnings Tax (¶251)

If a corporation permits earnings to accumulate instead of being distributed for the purpose of preventing the imposition of tax upon its shareholders, there is an additional tax (a penalty). The additional tax is equal to 15% of the corporation’s accumulated taxable income. Interest is calculated from the date the corporation's tax return is due without regard to extensions. Dividends Received (¶237)

Dividends received by one corporation from another are excluded from taxable income up to 1. 70% if the receiving corporation owns less than 20% (by stock vote and value) of the paying company 2. 80% if the receiving corporation owns at least 20% but less than 80% of the paying company 3. 100% if the receiving corporation owns 80% or more of the paying company (affiliated group)

Deductibility of Management Compensation (¶906):

Management compensation, including bonuses, must be reasonable to be deductible. Publicly-traded companies generally cannot deduct executive compensation to an individual of more than $1 million unless it is performance based compensation. Reasonable compensation is the amount that would ordinarily be paid for like services by like enterprises in like circumstances. Bonuses count as part of the calculations. Unfunded deferred compensation is deductible when the compensation is included in the gross income of the recipient. Compensation paid to a relative is deductible if the relative performs needed services that would otherwise be performed by an unrelated party and limited to the amount that would have been paid to a third party.

Capital Gains Tax (¶1738):

Corporations are taxed on net capital gains at the regular tax rate, but is limited to 35% for high-income companies that fall in a higher marginal tax bracket.

Capital Losses (¶1752):

Capital Losses for a tax year can only be used to offset capital gains (not ordinary income) in that year. There is no distinction between long-term and short-term capital gains.

Capital Loss Carryover and Carryback (¶1756):

A corporation may carry back a capital loss to each of the three tax years preceding the loss year. Any excess may be carried forward for five years following the loss year. Any undeducted loss remaining after the 3-year carryback and 5-year carryforward is not deductible. Carrybacks cannot cause or increase a net operating loss in the carryback year.

Net Operating Loss (NOL) Carryover and Carryback (¶1179)

NOLs may be carried back two years and carried forward for 20 years. (Pre- 1997 NOLs can only be carried forward for 15 years)

Amortization of Section 197 Intangibles (¶1288):

Section 197 Intangibles includes the following:

1. Goodwill 2. Covenants Not to Compete (typically 2-5 years) 3. Workforce in place 4. Information base (client list, etc.) 5. Patents, copyrights, trade marks and trade names 6. Licenses and permits granted by a governmental unit 7. Any franchise, trademark or trade name

Amortization is generally over a 15-year period beginning in the month of acquisition. The intangibles can only be amortized if created in connection with the acquisition of a trade or business.

When a business is sold, generally each asset of the business is treated as being sold separately in determining the seller's income, gain or loss and the buyer's basis in each of the assets acquired (¶1743). Under the residual method, the purchase price is allocated in the following order:

1. Class I Assets - Cash and cash equivalents 2. Class II Assets - CDs, U.S. government securities, marketable securities and foreign exchange 3. Class III Assets – mark-to-market assets and certain debt instruments 4. Class IV Assets – stock in trade and inventory 5. Class V Assets – all assets other than Class I, II, III, IV, VI and VII assets 6. Class VI Assets - Section 197 intangible assets except goodwill, going concern value; e.g., copyrights and covenants not to compete 7. Class VII Assets – Goodwill and going concern value

Thus, goodwill can be negative. In most cases, goodwill is positive and the amortization is a deduction against income. In some cases, however, goodwill is negative. This should only occur after uncollectible receivables, inventories and fixed assets have been written down and expensed. In the case of negative goodwill, the amortization will result in an addition to income (since it is a negative deduction). Note that negative goodwill can only be for tax purposes; for financial reporting purposes, a separate equity account is created in order to avoid negative goodwill.

Note on Company Sales: Most buyers of entire companies want to buy the assets since this is how they can get goodwill on the balance sheet and deductible over fifteen years as amortization expense. If the buying company simply buys the stock from the owner, it is carried on the balance sheet as Investment in Company XYZ. Even though the tax returns can be consolidated, this type of purchase does not create goodwill on the buyer's balance sheet.

The seller, on the other hand, wants to sell the stock of the company since this becomes a capital gain for them personally and is taxed at favorable tax rates (generally, 15%). Any goodwill generated by selling a company's assets creates income taxed at the corporate income tax rate (even capital gains). Worse, in order to get the income out of the company (which is the legal owner of the assets), a dividend distribution must be made which is taxed at the owner's personal tax rate for capital gains (except for the owner's cost basis which would be a liquidating dividend). Thus, owner's want to sell the stock of the company and not its assets.

Depreciation

1. Section 179 Expense Election (¶1208)

Up to $250,000 of depreciable assets may be expensed in 2009. The limitation is reduced to $134,000 and in 2010. Beginning in 2011 and thereafter, the limit is reduced to $25,000 and not adjusted for inflation. (There is a $25,000 limitation on certain sport utility vehicles, trucks and vans.) This deduction is allowable if Total capital expenditures do not exceed $800,000 for the year 2009. In 2010, it is reduced to $530,000 and, but for years 2011 and beyond, the limit is $200,000 and not adjusted for inflation. In addition, The total amount expensed does not exceed taxable income derived from the conduct of trade or business

2. Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) (¶1236 and ¶1240) – mandatory

Applies to most tangible property placed in service after 1986 (1) Three-year property: Tractor trucks designed to tow a trailer, rent-to- own consumer durables (televisions, furniture) (2) Five-year property: Cars, light and heavy general-purpose trucks, telephone central office switching equipment, semi-conductor manufacturing equipment, computers and peripheral equipment, and office machinery (typewriters, calculators, etc.), solar and wind energy properties (3) Seven-year property: Office furniture, equipment and fixtures; cell phones; fax machines and other communication equipment; most other business assets (4) 10-year, 15-year, 20-year and 25-year property: Generally related to marine transportation units (boats, barges), wastewater plants, land improvements (sidewalks, driveways, parking lots), utility property (water and sewer lines) (5) Rental real estate: Residential -- 27½ years Commercial -- 39 years

Most business property, other than real estate, falls in the 5- and 7-year categories, with the majority being 7-year property. The MACRS system is essentially a 200% (or double) declining balance method with a switch to straight-line depreciation when it maximizes the deduction. These two categories also use the mid-year convention. That is, whether you placed the asset in service on January 1 or December 31, it is assumed to have been placed in service in the middle of the year. The mid-year convention is the reason that a 5-year asset is depreciated over a total of six years, and a 7-year asset is depreciated over a total of eight years. In other words, you get one- half of the first year's deduction for the first year; in the second year, you get the other one-half of the first year's deduction plus one-half of the second year's deduction, etc. In the sixth year, you get the second half of the fifth year's depreciation deduction. The result is the following for a 5-year asset:

First year: Double-declining balance

100% * 1/5 * 200% = 40% 1/2 in Year 1 = 20%

1/2 in Year 2 20%

Year 2 Total = + 32% Second year: Double-declining balance (100% - 40%) * 1/5 * 200% = 24% 1/2 in Year 2 12%

1/2 in Year 3 12%

Year 3 Total = + 19.2% Third year: Double-declining balance (60% - 24%) * 1/5 * 200% = 14.4% 1/2 in Year 3 7.2% In the middle of year 3, after 2½ years of double-declining balance, it is advantageous to switch to straight-line over the remainder of the asset's life. Thus, with 2½ years of life remaining, we would get

Each half-year (five remain) thereafter:

(36% - 7.2%)/5 = 28.8%/5 = 5.76% per half-year

Fourth year: 5.76% per half-year * 2 half-years = 11.52%

Fifth Year: 5.76% per half-year * 2 half-years = 11.52%

Sixth Year: 5.76% per half-year * 1 half-year = 5.76%

Thus, the 5-year asset is actually depreciated over six years to a zero book value.

Year 1 + Year 2 + Year 3 + Year 4 + Year 5 + Year 6 =

20% + 32% + 19.2% + 11.52% + 11.52% + 5.76% = 100%

3. Straight-line Depreciation is an allowable alternative (¶1243)

Rather than using MACRS, a company can irrevocably elect to use straight- line depreciation over the MACRS life of the asset. Thus, there is no accelerated depreciation involved. The election would apply to all assets within a specific class (3-year, 5-year, etc.). Why would anyone want to do this if it increases their income in earlier years? In order to take advantage of NOL carryovers that would be getting ready to expire.

Remember that it is the exception when taxes are not applicable. The complexity and ever-changing nature of tax law is the reason that UTSA offers a Master of Accountancy degree with a Concentration in Taxation and every law school produces lawyers specializing in tax. At a minimum, one can buy a summary of tax laws such as Commerce Clearing House's Master Tax Guide or Prentice-Hall's Federal Tax Handbook as a starting reference for determining what tax implications might exist. Then, depending on the circumstances, it may well be worth consulting an expert.