Verifying Bilby Presence and the Systematic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tanami Regional Exploration Project (Tre)

TanamI Project - Regional Exploration MMP Variation NORTHERN STAR hllOilRCCS vfHMtD Exploration Operations Mining Management Plan and Public Report NORTHERN STAR (TANAMI) PTY LTD TANAMI REGIONAL EXPLORATION PROJECT (TRE) VARIATION Request for Additional Information MR2017/0336 DECEMBER 2017 Document Distribution List: NT Department of Primary industry and Resources Central Land Council Tanomi Gold ML Northern Star Resources Ltd I, MICHAEL MULRONEY - CHIEF GEOLOGICAL OFFICER declare that to the best of my knowledge the information contained in this Mining Management Plan is true and correct and commit to undertake the works detailed in this plan in accordance with all the relevant Local, Northern Territory and Commonwealth Government legislation. SiGNATU DATE: Northern Star (Tanami) Pty Ltd Page 1 of 22 Tanami Project – Regional Exploration MMP Variation Contents 1. AMENDMENTS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 Operator Details .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Project Details ....................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Proposed Activities ........................................................................................................................ -

Broken Hill Complex

Broken Hill Complex Bioregion resources Photo Mulyangarie, DEH Broken Hill Complex The Broken Hill Complex bioregion is located in western New South Wales and eastern South Australia, spanning the NSW-SA border. It includes all of the Barrier Ranges and covers a huge area of nearly 5.7 million hectares with approximately 33% falling in South Australia! It has an arid climate with dry hot summers and mild winters. The average rainfall is 222mm per year, with slightly more rainfall occurring in summer. The bioregion is rich with Aboriginal cultural history, with numerous archaeological sites of significance. Biodiversity and habitat The bioregion consists of low ranges, and gently rounded hills and depressions. The main vegetation types are chenopod and samphire shrublands; casuarina forests and woodlands and acacia shrublands. Threatened animal species include the Yellow-footed Rock- wallaby and Australian Bustard. Grazing, mining and wood collection for over 100 years has led to a decline in understory plant species and cover, affecting ground nesting birds and ground feeding insectivores. 2 | Broken Hill Complex Photo by Francisco Facelli Broken Hill Complex Threats Threats to the Broken Hill Complex bioregion and its dependent species include: For Further information • erosion and degradation caused by overgrazing by sheep, To get involved or for more information please cattle, goats, rabbits and macropods phone your nearest Natural Resources Centre or • competition and predation by feral animals such as rabbits, visit www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au -

Greater Bilby Macrotis Lagotis

Threatened Species Strategy – Year 3 Priority Species Scorecard (2018) Greater Bilby Macrotis lagotis Key Findings Greater Bilbies once ranged over three‑ quarters of Australia, but declined coincident with the spread of European foxes, along with habitat changes from introduced herbivores (especially rabbits), changed fire regimes and predation by feral cats. Recovery actions have focused on maintaining or restoring traditional Indigenous patchwork fire regimes and controlling introduced predators. Translocations into predator-free exclosures and a predator-free island have allowed for further increases in population and re- establishment into the species’ former range. Photo: Queensland Department of Environment and Science Significant trajectory change from 2005-15 to 2015-18? No, generally stable overall. Priority future actions • Effective landscape-scale fire management is implemented across all of distribution. • Targeted cat and rabbit control at key bilby sites. • Minimise loss of bilby habitat, and maintain connectivity between bilby populations. Full assessment information Background information 2018 population trajectory assessment 1. Conservation status and taxonomy 8. Expert elicitation for population trends 2. Conservation history and prospects 9. Immediate priorities from 2019 3. Past and current trends 10. Contributors 4. Key threats 11. Legislative documents 5. Past and current management 12. References 6. Support from the Australian Government 13. Citation 7. Measuring progress towards conservation The primary purpose -

The Role of the Reintroduction of Greater Bilbies (Macrotis Lagotis)

The Role of the Reintroduction of Greater Bilbies (Macrotis lagotis) and Burrowing Bettongs (Bettongia lesueur) in the Ecological Restoration of an Arid Ecosystem: Foraging Diggings, Diet, and Soil Seed Banks Janet Newell School of Earth and Environmental Sciences University of Adelaide May 2008 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Table of Contents ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................................I DECLARATION.......................................................................................................................................III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................... V CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 1.1 MAMMALIAN EXTINCTIONS IN ARID AUSTRALIA ...............................................................................1 1.2 ROLE OF REINTRODUCTIONS .......................................................................................................2 1.3 ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONS.............................................................................................................3 1.4 ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONS OF BILBIES AND BETTONGS .....................................................................4 1.4.1 Consumers..........................................................................................................................4 -

Phylogenetic Structure of Vertebrate Communities Across the Australian

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2013) 40, 1059–1070 ORIGINAL Phylogenetic structure of vertebrate ARTICLE communities across the Australian arid zone Hayley C. Lanier*, Danielle L. Edwards and L. Lacey Knowles Department of Ecology and Evolutionary ABSTRACT Biology, Museum of Zoology, University of Aim To understand the relative importance of ecological and historical factors Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA in structuring terrestrial vertebrate assemblages across the Australian arid zone, and to contrast patterns of community phylogenetic structure at a continental scale. Location Australia. Methods We present evidence from six lineages of terrestrial vertebrates (five lizard clades and one clade of marsupial mice) that have diversified in arid and semi-arid Australia across 37 biogeographical regions. Measures of within-line- age community phylogenetic structure and species turnover were computed to examine how patterns differ across the continent and between taxonomic groups. These results were examined in relation to climatic and historical fac- tors, which are thought to play a role in community phylogenetic structure. Analyses using a novel sliding-window approach confirm the generality of pro- cesses structuring the assemblages of the Australian arid zone at different spa- tial scales. Results Phylogenetic structure differed greatly across taxonomic groups. Although these lineages have radiated within the same biome – the Australian arid zone – they exhibit markedly different community structure at the regio- nal and local levels. Neither current climatic factors nor historical habitat sta- bility resulted in a uniform response across communities. Rather, historical and biogeographical aspects of community composition (i.e. local lineage per- sistence and diversification histories) appeared to be more important in explaining the variation in phylogenetic structure. -

Mcphee Creek Flora and Vegetation Survey 227 a T L a S I R O N

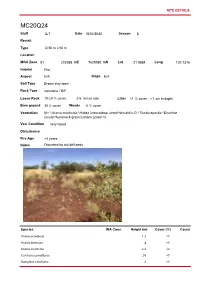

SITE DETAILS MC20Q24 Staff JLT Date 18/04/2020 Season E Revisit Type Q 50 m x 50 m Location MGA Zone 51 202985 mE 7609989 mN Lat. -21.5884 Long. 120.1316 Habitat Flat Aspect N/A Slope N/A Soil Type Brown clay loam Rock Type Ironstone / BIF Loose Rock 10-20 % cover; 2-6 mm in size Litter <1 % cover ; <1 cm in depth Bare ground 30 % cover Weeds 0 % cover Vegetation M+ ^Acacia monticola,^Hakea lorea subsp. lorea\^shrub\4\c;G ^Triodia epactia,^Eriachne lanata\^hummock grass,tussock grass\1\c Veg. Condition Very Good Disturbance Fire Age >5 years Notes Disturbed by old drill pads Species WA Cons. Height (m) Cover (%) Count Acacia acradenia P 1.3 <1 Acacia bivenosa P .2 <1 Acacia monticola P 2.4 22 Corchorus parviflorus P .35 <1 Dampiera candicans P .4 <1 SITE DETAILS Eriachne lanata P .3 65 Evolvulus alsinoides var. villosicalyx P .1 <1 Goodenia stobbsiana P .2 0.2 Grevillea wickhamii P 1.8 0.2 Hakea lorea subsp. lorea P 3 1 Hibiscus coatesii P .4 <1 Indigofera monophylla P .4 <1 Ptilotus calostachyus P .4 <1 Sida sp. Pilbara (A.A. Mitchell PRP 1543) P .3 <1 Triodia epactia P .4 8 Triumfetta maconochieana P .4 <1 SITE DETAILS MC20Q25 Staff JLT Date 12/04/2020 Season E Revisit Type Q 50 m x 50 m Location MGA Zone 51 195876 mE 7607806 mN Lat. -21.6069 Long. 120.0626 Habitat Flat Aspect N/A Slope N/A Soil Type Black haemotite over pale brown silt Rock Type Haemotite Loose Rock 10-20 % cover; 2-6 mm in size Litter <1 % cover ; <1 cm in depth Bare ground 50 % cover Weeds 0 % cover Vegetation U ^Corymbia hamersleyana\^tree\6\bi;M ^Acacia inaequilatera\^shrub\4\bi;G+ ^Triodia epactia\^hummock grass\1\c Veg. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Living and Recently Extinct Bandicoots Based on Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Sequences ⇑ M

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62 (2012) 97–108 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetic relationships of living and recently extinct bandicoots based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences ⇑ M. Westerman a, , B.P. Kear a,b, K. Aplin c, R.W. Meredith d, C. Emerling d, M.S. Springer d a Genetics Department, LaTrobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia b Palaeobiology Programme, Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Villavägen 16, SE-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden c Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia d Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA article info abstract Article history: Bandicoots (Peramelemorphia) are a major order of australidelphian marsupials, which despite a fossil Received 4 November 2010 record spanning at least the past 25 million years and a pandemic Australasian range, remain poorly Revised 6 September 2011 understood in terms of their evolutionary relationships. Many living peramelemorphians are critically Accepted 12 September 2011 endangered, making this group an important focus for biological and conservation research. To establish Available online 11 November 2011 a phylogenetic framework for the group, we compiled a concatenated alignment of nuclear and mito- chondrial DNA sequences, comprising representatives of most living and recently extinct species. Our Keywords: analysis confirmed the currently recognised deep split between Macrotis (Thylacomyidae), Chaeropus Marsupial (Chaeropodidae) and all other living bandicoots (Peramelidae). The mainly New Guinean rainforest per- Bandicoot Peramelemorphia amelids were returned as the sister clade of Australian dry-country species. The wholly New Guinean Per- Phylogeny oryctinae was sister to Echymiperinae. -

A New Genus of Scolopendrid Centipede (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha: Scolopendrini) from the Central Australian Deserts

Zootaxa 3321: 22–36 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new genus of scolopendrid centipede (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha: Scolopendrini) from the central Australian deserts JULIANNE WALDOCK1 & GREGORY D. EDGECOMBE2 1Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool, WA 6986, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 2The Natural History Museum, Department of Palaeontology, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The first new species of Scolopendridae discovered in Australia since L.E. Koch’s comprehensive revision in the 1980s is named as a new monotypic genus of the Tribe Scolopendrini, Kanparka leki n. gen. n. sp. Its distribution includes the Gibson and Little Sandy Deserts in Western Australia and the western part of the Tanami Desert in the Northern Territory. The new genus is especially distinguished from other scolopendrines by the spinulation of its robust ultimate legs, partic- ular the presence of spines on the femur and tibia in addition to the predominantly irregularly scattered spines on the prefe- mur. Cladistic analysis based on morphological characters resolves Kanparka in a clade with Scolopendra, Arthrorhabdus, Akymnopellis and Hemiscolopendra, within which Scolopendra is non-monophyletic. Key words: Centipedes, Scolopendridae, Western Australia, Northern Territory, taxonomy, phylogeny Introduction The scolopendrid centipedes of Australia were revised in a series of studies by L.E. Koch that drew upon Austra- lian museum collections amassed during survey programs in the 1960s through early 1980s, as well as historical material. -

CITES Cop16 Prop. 9 IUCN-TRAFFIC Analysis (PDF, 77KB)

Ref. CoP16 Prop. 9 Deletion of Lesser Bilby Macrotis leucura from Appendix I Proponent: Australia Summary: The Lesser Bilby Macrotis leucura was one of two species of bilby (genus Macrotis) in the bandicoot family (the Peramelidae). It was endemic to Australia where it occurred in arid regions in the interior. The last verified specimen was collected in 1931, although oral accounts by Aboriginals suggest that it may have survived into the 1960s. It has been classified as Extinct by IUCN since 1982. The reasons for its demise are unclear, although predation by introduced Red Foxes Vulpes vulpes and feral cats and habitat alteration have been implicated. Macrotis leucura, along with its sister-species the Greater Bilby Macrotis lagotis, was included in CITES Appendix I in 1975, when the Convention came into force, by which time it was almost certainly extinct. No trade in any specimens has ever been recorded under CITES. In the highly unlikely event of the species being rediscovered, it would be covered by Australian legislation that prohibits the export of native mammal species for commercial purposes and requires a permit for export for non-commercial purposes. Macrotis lagotis, which is easily distinguishable from M. leucura by its greater size and different colouration, is extant and classified as Vulnerable by IUCN. A very small amount of non-commercial trade in specimens of this species is recorded in the CITES trade database. Analysis: Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP15) notes in Annex 4 (Precautionary measures) that no species listed in Appendix I shall be removed from the Appendices unless it has been first transferred to Appendix II, with monitoring of any impact of trade on the species for at least two intervals between meetings of the Conference of the Parties (para. -

Acacia Monticola X Trachycarpa

WATTLE Acacias of Australia Acacia monticola J.M.Black x Acacia trachycarpa E.Pritz. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com See illustration. Family Fabaceae Distribution Occurs in the Pilbara region of north-western W.A. where it is known from a single collection along the railway access rd between Tom Price and Karratha. Description Resinous shrub to 4 m high. Bark red ‘Minni Ritchi’. Branchlets hirtellous. Stipules persistent, triangular, c. 1 mm long, scarious, brown. Phyllodes linear-oblanceolate, narrowed to a fine, brown, subulate, innocuous point 1–1.5 mm long, upper margin clearly broader than lower margin, 4–8 cm long, 3–4 mm wide, not rigid, ±straight, sparsely hirtellous; longitudinal nerves numerous with central one most evident, minor nerves often longitudinally anastomosing. Inflorescences simple; peduncles 15–30 mm long, hirtellous; spikes 10–15 mm long. Flowers 5-merous; calyx dissected for about ½ its length into oblong lobes. Pods (immature) narrowly oblong, flat, 2–6 cm long, c. 8 mm wide, mostly straight, sometimes twisted in the longitudinal plane, obscurely reticulate, with dense, short, soft, straight, white hairs; marginal nerves thickened. Seeds (immature) oblique. Habitat Grows in skeletal soil along a drainage line among low rocky hills. Specimens W.A.: between Tom Price and Karratha along railway access track, E.Thoma 853 (PERTH). Notes The putative hybrid status of this entity is suggested by field observations and from a critical examination of herbarium material. It is intermediate between the two parents in phyllode width. Another putative hybrid between A. -

Thylacomyidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 25. THYLACOMYIDAE KEN A. JOHNSON 1 Bilby–Macrotis lagotis [F. Knight/ANPWS] 25. THYLACOMYIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The family Thylacomyidae is a distinctive member of the bandicoot superfamily Perameloidea and is represented by two species, the Greater Bilby, Macrotis lagotis, and the Lesser Bilby, M. leucura. The Greater Bilby is separated from the Lesser Bilby by its greater size: head and body length 290–550 mm versus 200–270 mm; tail 200–290 mm versus 120–170 mm; and weight 600–2500 g versus 311–435 g respectively (see Table 25.1). The dorsal pelage of the Greater Bilby is blue-grey with two variably developed fawn hip stripes. The tail is black around the full circumference of the proximal third, contrasting conspicuously with the pure white distal portion, which has an increasingly long dorsal crest. The Lesser Bilby displays a delicate greyish tan above, described by Spencer (1896c) as fawn-grey and lacks the pure black proximal portion in the tail. Rather, as its specific name implies, the tail is white throughout, although a narrow band of slate to black hairs is present on the proximal third of the length. Finlayson (1935a) noted that the Greater Bilby lacks the strong smell of the Lesser Bilby. The skull of the Lesser Bilby is distinguished from the Greater Bilby by its smaller size (basal length 60-66 mm versus 73–104 mm; [Troughton 1932; Finlayson 1935a]), the more inflated and smoother tympanic bullae (Spencer 1896c), the absence of a fused sagittal crest in old males and the distinctly more cuspidate character in the crowns in the unworn molars (Finlayson 1935a). -

From the Tanami to Tanzania: Termite Adventures

Regolith 2006 - Consolidation and Dispersion of Ideas FROM THE TANAMI TO TANZANIA: TERMITE ADVENTURES Anna E. Petts CRC LEME, Dept. Geology & Geophysics, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, 5005 ABSTRACT Tanami Region of northwestern Australia and the highlands of northern Tanzania have long traditions mineral exploration, and many similarities in the impediments to exploration, such as thick regolith sediments. Companies such as Twigg Gold Ltd have long been recording regolith-landform details during sampling programs, and utilising this information in their interpretations of geochemical data to rank exploration targets. This data that has been collected by Twigg Gold may be collated to make quantifiable interpretations of regolith processes in northern Tanzania, therefore making it an attractive place to visit, as a companion to current Tanami regolith-landform and termitaria mapping and geochemical analysis of mound material. Regolith-landform mapping has proved a key tool for the mineral explorer in Australia, utilising geochemical data in a landscape and regolith context. Utilising company data and from observations made in the field, it is planned that regolith-landform maps and termitaria density studies based around company field sites in Tanzania will compliment similar studies in Australia. Key words: termitaria, regolith-landform mapping, Tanzania, Tanami Desert, geochemical exploration INTRODUCTION The tropical to semi-arid savannah of the southern hemisphere have proved to be highly prospective ground for mineral exploration. Both the Tanami Region of northwestern Australia and the sub-humid to tropical savannah and highlands of Tanzania have long traditions of gold and mineral exploration in general. Even though there are many similarities in weathering history, development of regolith profiles with substantial superficial cover and style of mineralisation, there has been a lack of discussion between explorers in both continents due to the overwhelming physical distance.