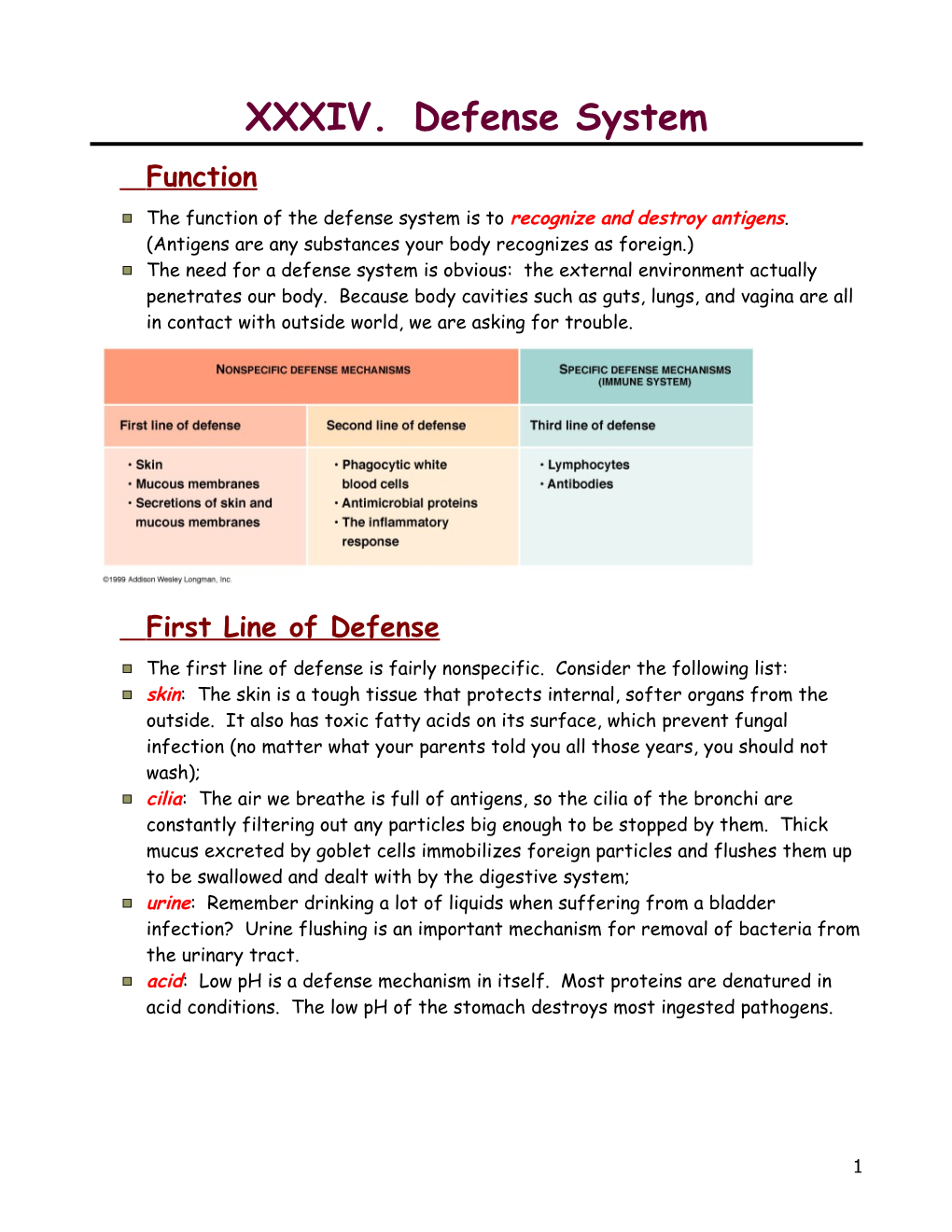

XXXIV. Defense System Function The function of the defense system is to recognize and destroy antigens. (Antigens are any substances your body recognizes as foreign.) The need for a defense system is obvious: the external environment actually penetrates our body. Because body cavities such as guts, lungs, and vagina are all in contact with outside world, we are asking for trouble.

First Line of Defense The first line of defense is fairly nonspecific. Consider the following list: skin: The skin is a tough tissue that protects internal, softer organs from the outside. It also has toxic fatty acids on its surface, which prevent fungal infection (no matter what your parents told you all those years, you should not wash); cilia: The air we breathe is full of antigens, so the cilia of the bronchi are constantly filtering out any particles big enough to be stopped by them. Thick mucus excreted by goblet cells immobilizes foreign particles and flushes them up to be swallowed and dealt with by the digestive system; urine: Remember drinking a lot of liquids when suffering from a bladder infection? Urine flushing is an important mechanism for removal of bacteria from the urinary tract. acid: Low pH is a defense mechanism in itself. Most proteins are denatured in acid conditions. The low pH of the stomach destroys most ingested pathogens.

1 platelets

serotonin

vasoconstriction

thromboplastin 1o clot prothrombin thrombin

fibrinogen fibrin

2o clot

blood clotting can be considered a form of defense because the breach in tissue integrity is plugged by the clot. Blood clotting is an example of a “cascade” mechanism, in which the product of one reaction is a catalyst of the subsequent reaction: (a) blood platelets aggregate upon exposure to collagen fibers of the injured blood vessel. The aggregate of platelets forms a primary clot; (b) platelets secrete serotonin, which stimulates vasoconstriction and restricts the blood flow to the affected area; (c) platelets also produce the protein thromboplastin, which catalyzes a series of cascading reactions; (d) thromboplastin (with the help of vitamin K, Ca, and others factors) cleaves the protein prothrombin to thrombin;

2 (e) thrombin in turn cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin; (f) fibrin makes a tough secondary clot. Secondary Defenses In addition to these fairly passive primary defense mechanisms, we have developed approaches that fight pathogens more actively. These mechanisms can be either nonspecific (i.e. involving no recognition of the pathogen) or very specific (identifying the pathogen and taking a specific course of action). Non-specific secondary defenses Chemical Many chemicals are released in response to tissue injury or pathogen penetration. They include: Histamine: a chemical released by the organism that causes dilation of capillaries at the infected area and facilitates migration of the lymphocytes and phagocytic cells. Kinins: molecules that attract phagocytic cells and also cause pain at nerve endings (pain is a defense mechanism itself).

Complement: a group of 20 plasma proteins that kill bacteria by making pores in bacterial cell membranes and also help recognition of the pathogen by coating the bacterial surface (opsonization). Complement-coated surface is more easily recognized by the immune cells. Interferon: a “wonder drug” that (i) blocks viral protein synthesis by phosphorylation of the Initiation Factor (phosphorylated eIF2 does not shuttle tRNA to ribosome); (ii) stimulates RNAase L, an enzyme that chews up mRNA and rRNA. Cellular Cellular response relies on the phagocytic action of the leukocytes. 3 The following is a typical scenario for such a response: following infection the released kinins and activated complement system attract leukocytes to the site of infection; leukocytes squeeze through capillary walls into infected tissues;

neutrophils are the first to attack (these are the foot-soldiers, 100 billion are produced per day in the bone marrow); they engulf the bacteria and devour them by endocytosis; eosinophils devour large complexes of opsonized antigens; they specialize in destruction of parasitic worms by attaching toxic granules to their body walls; monocytes are precursors of the macrophages; at the site of infection, monocytes undergo transformation to macrophages. Macrophages are the heavy cavalry of the defense system. They are most potent of the phagocytes, but in addition to simple phagocytosis, they process the devoured pathogen and present its parts on the cell surface to flag the arrival of foreign bodies. Specific secondary response Basic characteristics of the specific response are: (i) recognition of the antigen; (ii) specificity of the mounted response (only the antigen will be attacked); (iii) memory development (even after successful destruction of the invading pathogen subsequent invasions by the same agent will meet with accelerated response. The main players in the specific secondary response are lymphocytes. Immature lymphocytes undergo differentiation into T-cells (in the thymus) and into B-cells (in bone marrow and the liver). Upon differentiation, the B- and T- cells migrate to lymphoid tissue, where they sit and wait to be called into action. The specific response can be of two different kinds: humoral (incapacitation is achieved by antibodies) or cellular (where the T-cells destroy the pathogens).

4