1

Securities Regulation Professor Bradford Spring 2016

Exam Answer Outline

The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. In some cases, the result is unclear; the position taken by the answer outline is not necessarily the only justifiable conclusion.

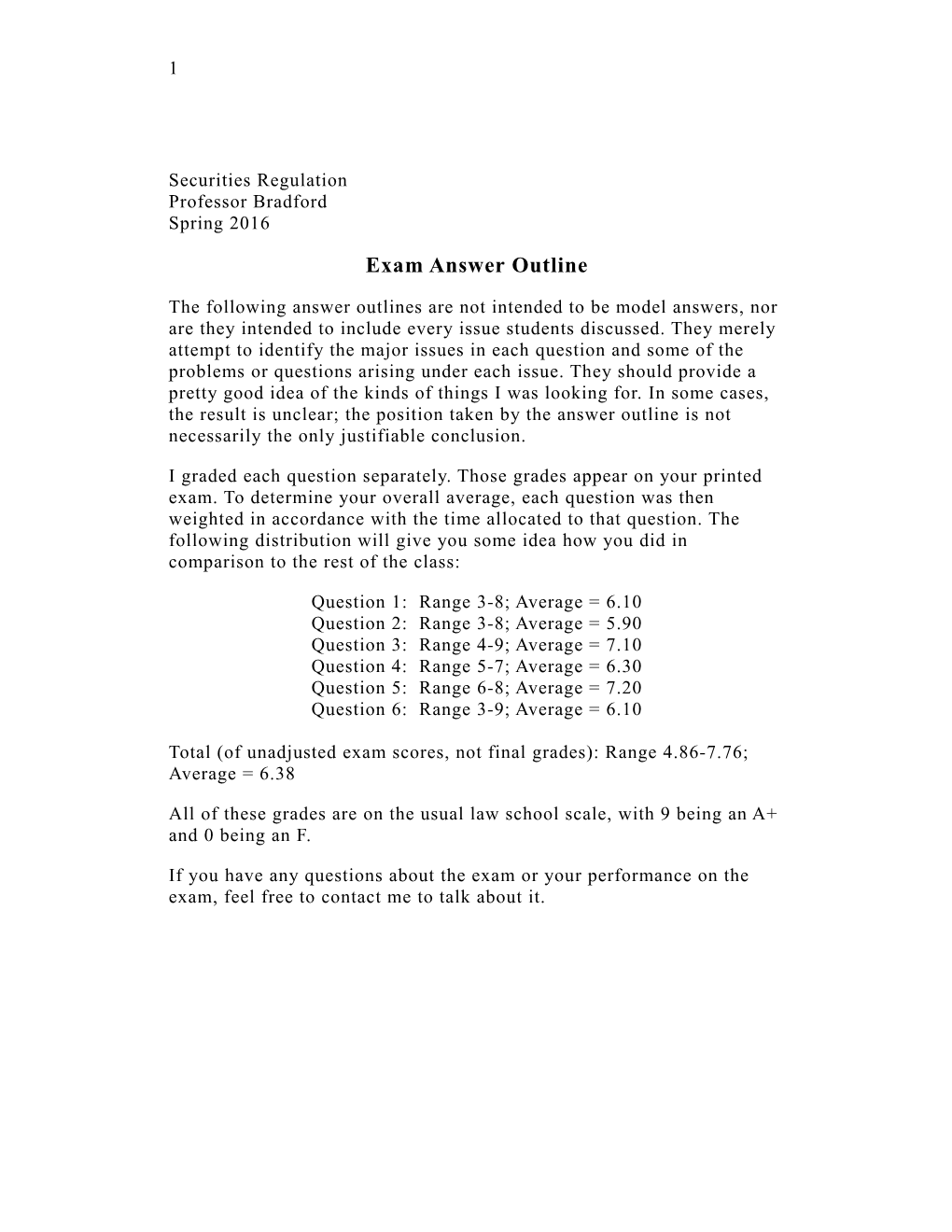

I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class:

Question 1: Range 3-8; Average = 6.10 Question 2: Range 3-8; Average = 5.90 Question 3: Range 4-9; Average = 7.10 Question 4: Range 5-7; Average = 6.30 Question 5: Range 6-8; Average = 7.20 Question 6: Range 3-9; Average = 6.10

Total (of unadjusted exam scores, not final grades): Range 4.86-7.76; Average = 6.38

All of these grades are on the usual law school scale, with 9 being an A+ and 0 being an F.

If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. 2

Question 1

A.

The most determinative factor is definitely the second: investors will receive ordinary common stock in return for their investment. Landreth Timber establishes that anything with the ordinary characteristics of common stock is a security, without any further test or analysis.

B.

This is a more difficult question. All three of the other factors have at least some relevance in determining whether something is a security, but the fourth factor is probably the least important.

4. The investment is in an industry that is very risky, so it is very uncertain whether investors will profit. This factor is probably the least important in determining whether an investment is a security. The Reves test for whether notes are securities considers whether there are risk- reducing factors such as government regulation or collateral which reduce the risk to investors. But this doesn’t really relate to whether the business itself is risky—just whether something else reduces that risk. Risk doesn’t matter much under Howey, either. Howey said that something can be an investment contract even if the enterprise is not speculative or promotional. Marine Bank v. Weaver held that a federally guaranteed certificate of deposit was not a security because investors didn’t need the protection of federal securities law. But that was based on government regulation and insurance, not the risk associated with the business itself.

1. The investment is being sold to a large number of purchasers. This factor is directly relevant in determining whether a note is a security. One of the Reves “family resemblance” factors is the plan of distribution, which considers, as one element, whether the notes are “offered and sold to a broad segment of the public.” This factor also has some relevance to the Howey investment contract test. Howey requires a common enterprise, which doesn’t require that there be a large number of purchasers, but it does require that there be more than one. This factor might also be relevant to another Howey factor—whether profits are to come primarily from the efforts of others. The greater the number of investors, the lower the likelihood that any particular investor will have effective control over profitability, even in a partnership. 3

3. The return to investors will depend on how well the business performs. This factor would satisfy one of the elements of both the Howey investment contract test and the Reves note test. Under Howey, investors must have an expectation of profits. That can be a fixed return. Edwards. But, if investors are receiving a share of the returns of the business, the “expectation of profits” element of Howey is clearly met. One of the Reves factors is the motivations of the buyers and seller. If the buyer of the note is motivated by the profits the note is expected to generate, the note is more likely to be a security. If the investors’ returns depend on the business’s profitability, that seems to point to a profit motivation. 4

Question 2

Materiality

Sections 11 and 17(a) and Rule 10b-5 all require that the misstatement be material. A misstatement is material if there’s a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important—or, to put it another way, if the investor would see it as significantly altering the total mix of information available to the investor. TSC Industries.

The magnitude of the correction is relatively small—only $10 million out of total sales of $740 million and $8 million out of a net income of $200 million. That’s only a 1.4% and 4% difference, which might not be enough quantitatively to be material. However, the misstatement is significant for two reasons other than its magnitude. First, it indicates problems with Issuer’s accounting system that might result in future issues. Second, it results in Issuer becoming the number two company in its industry, and that could have a more significant impact than the dollar amounts would otherwise indicate. Thus, even if the dollar amounts alone are not great enough proportionately to be material, these other factors could make the misstatements material.

The statement in the MD&A is a statement of opinion (“we believe”). If it’s an honestly held belief, as it appears to be since Issuer’s officers and directors were unaware of the fraud, it is not an untrue statement of material fact. See Omnicare. However, the statement of opinion presumes that Issuer is currently the leading company (“we will continue to be”). Omitting the crucial fact that Issuer is not currently the leading company could be material. See Omnicare.

Section 17(a)

None of the defendants is liable to Paula under section 17(a). The lower courts have consistently held that there is no private right of action under 17(a); it’s only available to the government.

Section 11

Tracing/Reliance

Section 11(a) grants a cause of action to “any person acquiring such security,” the security sold in the registered offering. It doesn’t matter that Paula didn’t purchase directly from Issuer If she can trace her shares 5

back to the offering, she’s a proper plaintiff. This was Issuer’s initial public offering so, unless some of the shares that existed prior to the offering have been resold, Paula clearly meets the tracing requirement. See Hertzberg.

It also doesn’t matter that Paula didn’t read the registration statement. She isn’t required to prove reliance.

Larry

Larry has no liability under section 11. That liability is limited to the defendants listed in § 11(a), and Larry does not fall into any of those categories. A lawyer is not an expert within the meaning of § 11(a)(4) merely because he drafted the registration statement.

Issuer

Issuer could be liable because it is required to sign the registration statement, and would therefore fall within § 11(a)(1). Issuer’s liability does not depend on the standard of care it exercised. It has no due diligence defense. See § 11(b) (“no person, other than the issuer . . .”).

Danielle

Danielle did not sign the registration statement, but she would still be a proper defendant as someone who was a director at the time of filing. § 11(a)(2). She is presumptively liable unless she can establish a due diligence defense.

She would definitely not be liable for the fraud in the financial statements. That material is “purporting to be made on the authority of an expert (other than himself)” [the auditors], so she only needs to establish that she had no reasonable ground to believe and did not believe it was false. § 11(b)(3)(C). No investigation is required. Danielle was unaware of the fraud, and, as far as we know, was unaware of any red flags, so she has established the defense.

Her situation is different as to the statement in the MD&A. That statement is not purporting to be made on the authority of an expert, so it falls within subsection 11(b)(3)(A). Danielle must establish that she had “after reasonable investigation, reasonable ground to believe, and did believe” that the statement was truthful. 6

Danielle did an investigation. She read the registration statement and spent 3 hours grilling the CEO and CFO. However, Escott v. BarChris says that just asking questions is not enough; the defendant must look at the underlying documents. If Danielle had done so, the fraud would have been apparent. Therefore, Danielle probably can’t establish her due diligence defense as to the false statement in the MD&A.

Damages

Paula’s presumptive recovery is the difference between the price Paula paid for the security (since that’s lower than the offering price) and the value at the time of suit, usually the $45 market price at that time. See § 11(e). The liability would, therefore, be $5/share.

However, § 11(e) contains a negative causation defense. The defendants in a § 11 action can avoid liability to the extent they can prove the loss results from something other than the disclosure of the fraud.

The price fell $5 immediately after the disclosure, which would seem to indicate that the drop was because of the fraud. However, the market index and the stock price of Issuer’s competitor, presumably a comparable company, fell by as much or more. Issuer could argue that this indicates the price drop was due to market factors other than the fraud, since the stock prices of all companies were dropping. It’s unclear if this is enough to meet Issuer’s burden of proof. The court accepted a similar argument in Akerman v. Oryx, but, in that case, the price didn’t drop at all after disclosure; the drop was all prior to disclosure. Here, there was a drop after disclosure, so Paula’s case is stronger.

Finally, if Danielle is an outside director, her liability would be limited based on her percentage of responsibility for the fraud, since she didn’t have actual knowledge of the fraud. See § 11(f)(2)(A); Exchange Act § 21D(f)(2).

Rule 10b-5.

Larry and Danielle

Neither Larry nor Danielle would be liable under Rule 10b-5. Janus Capital says that only makers are liable under Rule 10b-5 for fraudulent statements. A maker is one who has the ultimate authority over the statement, including its content and whether and how to communicate it. 7

Janus Capital. Merely drafting a statement, as Larry did, does not make one a maker. Id.

Larry and Danielle also would not be liable to Paula for aiding and abetting Issuers’ fraud. There is no private right of action for aiding and abetting a Rule 10b-5 violation. Central Bank.

Issuer

Issuer is a proper defendant. The fraud appeared in its registration statement, so it was clearly the maker of the fraudulent statement.

Scienter

Issuer is liable only if it acted with scienter, an intent to defraud. In the context of a corporation, it’s not enough that someone within the corporation knew about the fraud. Those responsible for the content and approval of the statement, in this case the officers and directors, must have acted with scienter. None of them were aware of the fraud, so Issuer did not have actual knowledge.

However, the lower courts have held that recklessness is sufficient for scienter. Unfortunately, the line between recklessness and mere negligence is uncertain. Issuer probably was negligent, since a simple check of the contracts would have shown that the contracts did not exist. However, it’s not clear that merely relying on the corporate accounting records and not checking the underlying documentation constitutes recklessness. If not, Issuer is not liable.

Causation

In an action pursuant to Rule 10b-5, the plaintiff has the burden of proving causation—both transaction causation and loss causation.

Transaction causation

The ordinary way of proving transaction causation is by proving reliance. Paula did not rely on the fraud because she didn’t even read the registration statement. However, Paula may use the fraud-on-the-market theory accepted by Basic and Halliburton. The statements in the registration statement were clearly public. If Paula can show that the market for Issuer stock is efficient, transaction causation is presumed, unless Issuer can show that the fraud did not affect the market price. 8

Loss causation

As a preliminary matter, Paula appears to have met her burden of showing loss causation. Issuer’s stock price dropped after disclosure. Dura Pharmaceuticals. However, Issuer might be able to rebut Paula’s prima facie case using the same evidence discussed under section 11. The difference is that here, unlike section 11, Paula bears the burden of proof. 9

Question 3

A.

This does not affect the availability of the exemption. Rule 506(b) has no dollar limit.

B.

This does not affect the availability of the exemption.

Rule 506(b) offerings must satisfy all the terms and conditions of Rule 502. Rule 506(b)(1). Rule 502(c)(1) prohibits any “general solicitation or general advertising.” The SEC staff has interpreted that to bar solicitations of investors unless the issuer or broker acting on its behalf has a preexisting relationship with those investors. That’s not a problem here because the written solicitation goes only to Broker’s existing brokerage customers. Broker has a preexisting relationship with those customers and that suffices to avoid a general solicitation. Gamma does not have to have a preexisting relationship with those investors as long as Broker, the person selling on its behalf, does.

C.

This does not affect the availability of the exemption.

Number of purchasers. Rule 506(b)(2)(i) limits the number of purchasers to 35. However, accredited investors are excluded in determining the number of purchasers. Rule 501(e)(1)(iv). The 80 corporations are accredited investors under Rule 501(a)(3)—“Any . . . corporation . . . with total assets in excess of $5,000,000.” Entities are ordinarily counted as a single purchaser. Rule 501(e)(2). An exception applies if, as in the case of the two general partnerships, they’re formed specifically for the offering. Thus, we count the general partners separately. Rule 501(e)(2). However, each of the general partners is also an accredited investor, Rule 501(a)(5), so they also aren’t counted. Rule 501(e)(1)(iv). Thus, there’s no problem with the 35-purchaser limit.

Sophistication requirement. Each purchaser who is not an accredited investor must meet a sophistication requirement. Rule 506(b)(2)(ii). That requirement won’t apply to the 80 corporations because, as previously discussed, they’re accredited investors. The 10 individuals with a net worth of $5 million are accredited investors, Rule 501(a)(5), so it doesn’t 10

matter that they aren’t sophisticated. The 5 directors are also accredited investors. Rule 501(a)(4). The partnerships are accredited investors. Rule 501(a)(8). The three individual investors don’t meet the income or wealth requirements, so they’re not accredited investors. See Rule 501(a) (5),(6). But they appear to be sophisticated, so they satisfy the requirement.

D.

This does not affect the availability of the exemption. The disclosure requirement in Rule 502(b)(2) does not apply to accredited investors. As previously discussed, the corporate investors are accredited investors, so it doesn’t matter that they didn’t receive the required disclosure.

E.

This does not affect the availability of the exemption.

This raises a potential integration issue since the Rule 504 offering involved the same security, was for the same cash consideration, appears to have been for the same general purpose (equipment purchase) and might have been part of a single plan of financing. There would be a problem if the two offerings were integrated because some of the purchasers in the earlier offering would not meet the sophistication requirement in Rule 506(b)(2)(ii).

However, the two offerings are protected from integration by Rule 502(a), assuming there were no other sales in the period between the Rule 504 offering and the Rule 506 offering. Rule 502(a) says that offers and sales more than 6 months before or after a Regulation D offering will not be considered part of that Regulation D offering. Thus, those earlier Rule 504 offers and sales will not be considered part of the current Rule 506(b) offering. It therefore doesn’t matter that some of those purchasers would not meet the sophistication requirement in 506(b)(2)(ii).

Question 4

Section 3(a)(9) exempts “securities exchanged by the issuer with its existing security holders exclusively.” 11

By the issuer. To qualify for the exemption, Acme must be the issuer of the securities being exchanged. Acme is the issuer of both the common stock and the preferred being exchanged, so that requirement is met.

No commission or other remuneration. Section 3(a)(9) provides that no commission or other remuneration may be paid “directly or indirectly for soliciting such exchange.” Acme’s treasurer, who spends several hours explaining why the three shareholders should do the exchange, is undoubtedly soliciting them. However, he’s not being paid a commission or any other remuneration for that solicitation—or at least the question doesn’t indicate that he is. He’s doing this as part of his duties for Acme, and he undoubtedly receives a salary for those duties, but he’s not receiving any additional compensation just for the solicitation. If he is being paid separately for the solicitation, then section 3(a)(9) is not available. But, assuming that’s not the case, this requirement is met.

Exchange: No additional consideration. The transaction must be exclusively an exchange of securities. The security holders cannot be required to pay any additional consideration for the exchange. They are not. It’s not exclusively an exchange of securities from Acme’s standpoint; Acme is paying the shareholders $20 cash for each share. However, Rule 150 allows additional payments to flow from the issuer to the security holders.

Exclusively an exchange. Finally, the entire transaction must be “exclusively” an exchange with the existing security holders to qualify under section 3(a)(9). This raises an integration issue. Acme is selling the same preferred stock for cash to accredited investors; this is not an exchange of securities with existing security holders. If these two transactions are considered part of the same offering, then that integrated offering does not qualify for section 3(a)(9).

No integration safe harbors are available. Therefore, we must apply the five-factor integration test to determine whether these two transactions are part of the same offering. The five factors are (1) whether the two transactions are part of a single plan of financing; (2) whether the same class of security is being sold; (3) whether the two transactions are at or about the same time; (4) whether the consideration paid is the same; and (5) whether the two offerings are for the same general purpose. No one factor is determinative, and all five factors do not have to point to integration for the two transactions to be integrated. 12

Three of the factors clearly favor integration. The same class of security is being sold in the two offerings—preferred stock. The two transactions are at exactly the same time. And this appears to be a single plan of financing: the two transactions were conceived at exactly the same time and are intertwined. Neither transaction would occur without the other.

One factor clearly points against integration. The same consideration is not being paid for the preferred stock. The shareholders are giving up their common shares for the preferred stock; the accredited investors are paying cash.

The final factor is whether the offerings are for the same general purpose. One transaction—the exchange—is designed to facilitate the three shareholders’ withdrawal from the business. The other transaction is intended to raise cash. But the two transactions are interrelated; the cash offering is to provide cash to facilitate the exchange. Thus, although one could argue that the purposes are different, given the tie between the two transactions, this factor does not point strongly against integration.

The application of the five-factor test is always uncertain. Any one factor might be determinative. But given the closeness of the two offerings under the five-factor test, integration is a strong possibility.

If the two transactions are part of the same offering, then section 3(a)(9) is not available because the integrated offering is not exclusively an exchange with existing shareholders. 13

Question 5

Delta’s notice violates section 5(c) of the Securities Act, which makes it unlawful to “offer to sell” any security unless a registration statement has been filed. The registration statement had not yet been filed when this notice was sent and the notice is probably an offer to sell.

Offer to Sell

“Offer to sell” is defined as “every attempt or offer to dispose of, or solicitation of an offer to buy, a security or interest in a security, for value.” § 2(a)(3). The notice did not expressly ask anyone to purchase the preferred stock, but the SEC has indicated that an express offer is not necessary if the communication “contribute[s] to conditioning the public mind or arousing public interest in the issuer or in the securities of an issuer in a manner which raises a serious question whether the publicity is not in fact part of the selling effort.” Securities Act Release No. 3844. This communication includes positive information about Delta and its products, and it’s tied to information about the offering. That’s probably enough to constitute conditioning the market, and thus make this an offer to sell.

There’s an exception in the definition of “offer to sell” for communications by brokers and dealers relating to emerging growth companies, but this communication was directly by Delta, so the exception doesn’t help.

Possible Rules

The SEC has adopted several rules that say that something that might otherwise be an offer to sell is not, for purposes of section 5(c). However, none of those rules is available.

Rule 163A

Rule 163A is not available. This communication is more than 30 days prior to the filing of the registration statement, as required by Rule 163A(a), but 163A protects only a communication that “does not reference a securities offering.” Rule 163A(a). The notice discusses the offering.

Rule 169 14

The same problem arises under Rule 169. It excludes from its ambit a communication “containing information about the registered offering.” Rule 169(c). In addition, Rule 169 only allows communications containing “factual business information.” Rule 169(a). The statements about future plans are not factual business information. Compare Rule 169(b)(1) to Rule 168(b)(1),(2).

Rule 168

Rule 168 is not available because Delta is not a reporting company. Rule 168(a). In any event, it has the same restriction as Rule 169 regarding information about the offering. See Rule 168(c).

Rule 163

Rule 163 is only available to well-known seasoned issuers. Rule 163(a). Delta, is not even a reporting company, much less a WKSI.

Rule 134

Rule 134 is not available, because it applies only to communications after a registration statement has been filed. Rule 134(a).

Rule 135

Rule 135 also does not help. A Rule 135 communication must include the notice specified in Rule 135(a)(1). There’s no evidence that Delta’s communication included the required notice. Even if it did, Rule 135 protects only communications that include “no more than” the specific information listed in Rule 135(a)(2). The detailed information about Delta’s improved product and the statement that Delta expects the product to be highly successful both go beyond what 135(a)(2) allows. Everything else seems acceptable, however.

Rule 433

Rule 433, the free-writing prospectus rule, is not available. It only applies after the registration statement has been filed. Rule 433(a).

Section 5(d)

Section 5(d) allows an emerging growth company to communicate with qualified institutional buyers or institutional accredited investors without violating section 5(c), but at least some of the customers are individuals, 15

so this wouldn’t help even if all of the companies are QIBs or accredited investors. 16

Question 6

Although some of Beta’s stock is traded on the NASDAQ exchange, Jones’s stock is restricted. It was acquired in a Rule 506(b) offering and therefore is subject to the resale restrictions in Rule 502(d). Jones cannot resell it unless Beta registers the resale or he has an exemption.

Registration. Jones can resell the stock if Beta registers his resale, but they’re unlikely to go to the expense of registration just to facilitate the sale of 1,000 shares by a shareholder.

Rule 144. Rule 144 is not currently available to Jones. Jones is not an affiliate and Beta is subject to the reporting requirements of the Exchange Act, so Rule 144(b)(1)(i) governs. To have the exemption, Jones must comply with the conditions in subsections (c)(1) and (d).

Jones has held the stock for 9 months so he is in compliance with the 6- month holding period in (d)(1)(i) that applies to the securities of reporting companies. The condition in (c)(1) is not met because Beta has not filed all required reports during the preceding 12 months. Its latest 10Q has not been filed. However, if Jones waits another 3 months, section (b)(1)(i) says the condition in (c)(1) would no longer apply, so he could sell it even though Beta had not filed all of its required reports.

Rule 144A. Jones cannot use Rule 144A to sell to a qualified institutional buyer. To qualify for the 144A exemption, Jones must meet the conditions in paragraph (d) of the rule. Rule 144A(b). Among other things, the securities sold may not be of the same class as securities listed on a national securities exchange. Rule 144A(d)(3)(i). Beta’s common stock is listed on the NASDAQ exchange, so this fungibility requirement is not met.

Section 4(a)(7). Jones could use the new exemption in section 4(a)(7) of the Securities Act. He may not engage in any general solicitation or general advertising, section 4(d)(2), and he may sell only to accredited investors. Section 4(d)(1). The information requirement in (d)(3) does not apply because it applies only if the issuer is not subject to the reporting requirements.

Section 4(a)(1). Finally, Jones may use the section 4(a)(1) exemption. Section 4(a)(1) would be unavailable if Jones or anyone selling on his behalf is an underwriter. 17

No one selling on behalf of Jones would be an underwriter because Jones is not an issuer as defined in section 2(a)(11) (either the issuer itself or a control person of the issuer). See section 2(a)(11).

Jones would be an underwriter if he purchased from the issuer with a view to distribution. § 2(a)(11). Jones has only held the stock for 9 months, and that’s insufficient to establish investment intent under the case law. The securities have not come to rest. But he would still not be an underwriter if his resale was not a distribution. For a non-affiliate like Jones selling before the securities come to rest, it’s not a distribution if his resales are consistent with the issuer’s original exemption. Here, Beta’s sale to Jones was pursuant to Rule 506(b), the safe harbor for section 4(a)(2). Jones’s resale would not be a distribution if he also sold consistently with the requirements of that private offering exemption—to purchasers who can fend for themselves.