PIONEERS by Christine Clark, Muir ’06

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preuss Teacher Convicted of Molesting Student to Them by Dr

VOLUME 50, ISSUE 40 MONDAY, JUNE 5, 2017 WWW.UCSDGUARDIAN.ORG CAMPUS CAMPUS THROWING IT Team of UCSD BACK Students to Brew Beer on Moon ILLUSTRATION BY MICHI SORA The team is partnering with fellow finalists to take a beer- A LOT CAN HAPPEN IN THE brewing canister into orbit. SPAN OF 50 YEARS. FROM FOOD AND DRINK TO FASHION BY Armonie Mendez ON A NIGHT OUT, THE News Editorial Assistant UCSD STUDENT LIFESTYLE A team of 11 UC San Diego HAS FOUND ITS FOOTING students who lost after competing in THROUGH REPEATING AND Google’s Lunar XPRIZE competition CONTEXTUALIZING WITH as finalists have been given a second THE TIMES. NEVERTHELESS, chance to take their project to HERE’S TO HOPING THE BEST “From lef to right: New AS Pres. Richard Altenhof and AS Vice-Pres. Herv Sweetwood are shown receiving the gavel of authority from Jim the moon after teaming up with Hefin and Richard Moncreif at the Installation of Ofcers. Te ceremony was held at Torrey Pines Inn on May 19.” Synergy Moon, a fellow competitor FOR THE NEXT 50. Triton Times, Volume I Issue I. in Google’s contest. LIFESTYLE, PAGE 8 The student team, known as Original Gravity, commenced the experiment back in August 2016 SENIOR SEND-OFFS PREUSS after being involved in another CLass of 2017 student competition introduced FEATURES, Page 6 Preuss Teacher Convicted of Molesting Student to them by Dr. Ramesh Rao, a professor at the Jacobs School of By Rebecca CHong Senior Staff Writer Engineering. COMMENCEMENT SPEAKER “The objective of that reuss School teacher Walter Solomon, who had students or staff. -

An Improbable Venture

AN IMPROBABLE VENTURE A HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO NANCY SCOTT ANDERSON THE UCSD PRESS LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA © 1993 by The Regents of the University of California and Nancy Scott Anderson All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Anderson, Nancy Scott. An improbable venture: a history of the University of California, San Diego/ Nancy Scott Anderson 302 p. (not including index) Includes bibliographical references (p. 263-302) and index 1. University of California, San Diego—History. 2. Universities and colleges—California—San Diego. I. University of California, San Diego LD781.S2A65 1993 93-61345 Text typeset in 10/14 pt. Goudy by Prepress Services, University of California, San Diego. Printed and bound by Graphics and Reproduction Services, University of California, San Diego. Cover designed by the Publications Office of University Communications, University of California, San Diego. CONTENTS Foreword.................................................................................................................i Preface.........................................................................................................................v Introduction: The Model and Its Mechanism ............................................................... 1 Chapter One: Ocean Origins ...................................................................................... 15 Chapter Two: A Cathedral on a Bluff ......................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: -

Case Study: San Diego

Building the Innovation Economy City-Level Strategies for Planning, Placemaking, and Promotion Case study: San Diego October 2016 Authors: Professor Greg Clark, Dr Tim Moonen, and Jonathan Couturier ii | Building the Innovation Economy | Case study: San Diego About ULI The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to • Advancing land use policies and design ULI has been active in Europe since the early provide leadership in the responsible use of practices that respect the uniqueness of 1990s and today has over 2,900 members land and in creating and sustaining thriving both the built and natural environments. across 27 countries. The Institute has a communities worldwide. particularly strong presence in the major • Sharing knowledge through education, Europe real estate markets of the UK, Germany, ULI is committed to: applied research, publishing, and France, and the Netherlands, but is also active electronic media. in emerging markets such as Turkey and • Bringing together leaders from across the Poland. fields of real estate and land use policy to • Sustaining a diverse global network of local exchange best practices and serve practice and advisory efforts that address community needs. current and future challenges. • Fostering collaboration within and beyond The Urban Land Institute is a non-profit ULI’s membership through mentoring, research and education organisation supported dialogue, and problem solving. by its members. Founded in Chicago in 1936, the institute now has over 39,000 members in • Exploring issues of urbanisation, 82 countries worldwide, representing the entire conservation, regeneration, land use, capital spectrum of land use and real estate formation, and sustainable development. development disciplines, working in private enterprise and public service. -

Water, Capitalism, and Urbanization in the Californias, 1848-1982

TIJUANDIEGO: WATER, CAPITALISM, AND URBANIZATION IN THE CALIFORNIAS, 1848-1982 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Hillar Yllo Schwertner, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 14, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Hillar Yllo Schwertner All Rights Reserved ii TIJUANDIEGO: WATER, CAPITALISM, AND URBANIZATION IN THE CALIFORNIAS, 1848-1982 Hillar Yllo Schwertner, M.A. Dissertation Advisor: John Tutino, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This is a history of Tijuandiego—the transnational metropolis set at the intersection of the United States, Mexico, and the Pacific World. Separately, Tijuana and San Diego constitute distinct but important urban centers in their respective nation-states. Taken as a whole, Tijuandiego represents the southwestern hinge of North America. It is the continental crossroads of cultures, economies, and environments—all in a single, physical location. In other words, Tijuandiego represents a new urban frontier; a space where the abstractions of the nation-state are manifested—and tested—on the ground. In this dissertation, I adopt a transnational approach to Tijuandiego’s water history, not simply to tell “both sides” of the story, but to demonstrate that neither side can be understood in the absence of the other. I argue that the drawing of the international boundary in 1848 established an imbalanced political ecology that favored San Diego and the United States over Tijuana and Mexico. The land and water resources wrested by the United States gave it tremendous geographical and ecological advantages over its reeling southern neighbor, advantages which would be used to strengthen U.S. -

![2018-2019 ● WCSAB [-] ● RFAB [Allison Kramer] ❖ Campus-Wide Cost of Electricity Is Going up 226% (Not a Typo) Over the Next 5 Years](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2122/2018-2019-wcsab-rfab-allison-kramer-campus-wide-cost-of-electricity-is-going-up-226-not-a-typo-over-the-next-5-years-1252122.webp)

2018-2019 ● WCSAB [-] ● RFAB [Allison Kramer] ❖ Campus-Wide Cost of Electricity Is Going up 226% (Not a Typo) Over the Next 5 Years

REVELLE COLLEGE COUNCIL Thursday, May 3rd, 2018 Meeting #1 I. Call to Order: II. Roll Call PRESENT: Andrej, Hunter, Amanda, Allison, Elizabeth, Art, Eni, Natalie, Isabel, Emily, Blake, Cy’ral, Anna, Samantha, Patrick, ,Dean Sherry, Ivan, Reilly, Neeja, Edward, Patrick, Earnest, Crystal, Garo EXCUSED: Allison, Mick, Miranda, Natalie UNEXCUSED: III. Approval of Minutes IV. Announcements: V. Public Input and Introduction VI. Committee Reports A. Finance Committee [Amanda Jiao] ● I have nothing to report. B. Revelle Organizations Committee [Crystal Sandoval] ● I have nothing to report. C. Rules Committee [Andrej Pervan] ● I have nothing to report. D. Appointments Committee [Hunter Kirby] ● I have nothing to report. E. Graduation Committee [Isabel Lopez] ● I have nothing to report. F. Election Committee [-] G. Student Services Committee [Miranda Pan] ● I have nothing to report. VII. Reports A. President [Andrej Pervan] ● I have nothing to report. B. Vice President of Internal [Hunter Kirby] ● I have nothing to report. C. Vice President of Administration [Elizabeth Bottenberg] ● I have nothing to report. D. Vice President of External [Allison Kramer] ● I have nothing to report. E. Associated Students Revelle College Senators [Art Porter and Eni Ikuku] ● I have nothing to report. F. Director of Spirit and Events [Natalie Davoodi] ● I have nothing to report. G. Director of Student Services [Miranda Pan] ● I have nothing to report. H. Class Representatives ● Fourth Year Representative [Isabel Lopez] ❖ I have nothing to report. ● Third Year Representative [Emily Paris] ❖ I have nothing to report. ● Second Year Representative [Blake Civello] ❖ I have nothing to report. ● First Year Representative [Jaidyn Patricio] ❖ I have nothing to report. I. -

Eleanor Roosevelt College Thurgood Marshall

ERC Res HallsEarth Geneva North Biology Europe Field Ridge Walk Ridge Eleanor RooseveltERC Hopkins Drive Drive Hopkins Station Residence Life Institute of ERC Apts the Americas RIMAC Arena Earl Warren Latin RIMAC Arena Residential America AptsOceania Housing Kathmandu Earth EARL’S North South America PLACE & MARKET Harlan ELEANOR Cuzco Canyon Vista ELEANOR Residence Warren & Earl’s Place Halls ROOSEVELTROOSEVELT San Diego CANYON Frankfurter College Pangea Parking Asante IR/PS Supercomputer Structure VISTA Stewart Res Halls COLLEGECOLLEGE WaterCenter International Earl Warren House Residential Life Great Hall Social Graduate Brown Pangea Drive Sciences Thurgood Marshall Lane WARREN Apts Thurgood e Thurgood GOODY’S an TMC Residence Halls y L Marshall COLLEGE Parking lit Marshall a Bates Thurgood PLACE & MARKET u Residential Res Halls q Thurgood E Douglas Housing Marshall SINGLE GRAD MarshallUpper Voigt Drive ApartmentsUpper Apts Ridge Walk Goldberg Warren APARTMENTS Thurgood OceanView Thurgood Marshall College Residential Life MarshallThurgood Undergraduate Brennan Terrace Marshall ApartmentsApts OCEANVIEW LowerLower Apts THURGOODMarshall Apartments Student TERRACE College Field Economics Activities Center THURGOOD MARSHALLSequoyah Justice Lane Justice Hall PARTY Black MARSHALL Scholars Drive North Powell-FochtWARREN Mail Services ThurgoodCOLLEGE Marshall STATION Bioengineering Bldg. A COLLEGE Provost Engineering-I Hall Marshall Media Center & #1 COLLEGE College Communications Eucalyptus Admin. Point Jacobs School of Engineering Canyonview -

Choose the Right Dining Plan for You

Choosing Your Choosing Your DINING PLAN DINING Everything you need to know about HDH Dining Services at UC San Diego 1 2021/2022 WELCOME TO HOUSING DINING HOSPITALITY @ UC San Diego Congrats! UC San Diego Dining Services is committed We are excited that you’ve chosen UC San Diego. If you to the health and safety of our students, choose to live on campus, your housing package will include faculty, and staff. a Dining Plan that is good for use at multiple Dining Services We are following guidelines set by local, state, and national restaurants, markets, and specialty locations across campus. health officials and we are consistently evolving to meet current county health guidelines. Our HDH Dining Facilities operate like any restaurant or market located outside of campus—decide to purchase as We routinely monitor our Dining Facilities and have much or as little as you need, and pay only for those items. implemented the following additional measures to ensure Table of Contents This “à la carte” style of service is designed to provide customer safety. flexibility, so that you’re not charged a flat rate just to walk For our current health and safety guidelines please visit through the door. hdh.ucsd.edu to review our HDH Covid-19 FAQ The Dining Plans . 4 Choosing the Right Plan for You + ACF Certified Chefs . 5 Sample Menu Items . 6 Allergen/Specialty Diets . 7 Markets + Special Events . 8 Triton2Go . 9 Employment + Triton Card Account Services . 10 Checklist + Quick Contacts . 11 Dining Index . 12 Campus Map . 13 2 3 THE DINING PLANS CHOOSING THE RIGHT The Dining Plans are designed to provide flexibility, with the understanding that “I love the convenience of being able you will occasionally be eating off campus, going home for weekends, or cooking PLAN FOR YOU to use my Dining Dollars whenever I in your residential unit. -

REVELLE COLLEGE COUNCIL Thursday, May 1, 2014 Meeting #1

REVELLE COLLEGE COUNCIL Thursday, May 1, 2014 Meeting #1 I. Call to Order: 5:15pm II. Roll Call PRESENT: Colin, Soren, Atiyeh, Josh F., Gino, Kasey, Dane, Jan, Jordan, Khalid, Wonhi, Francesca, Jeremy, Ben, Pom, Ellen, Cody, April EXCUSED: Katie, Katerina, Billy, Josh Y. , Prasad, Ryan, Donggun, Tasha UNEXCUSED: III. Approval of Minutes IV. Announcements: V. Public Input and Introduction A. Andre, Marco VI. Items of Immediate Consideration VII. Reports A. Finance Committee [Colin Opp] ● B. President [Soren Nelson] ● Appointments Committee Jan, Josh F., Kasey, Pom, Colin 6‐0‐5 Passed ● Finance Committee Francesca, Gino, Jeremey, Ben 8‐0‐2 Passed ● Elections Committee Rep. for Transportation Referendum Special Elections Jeremy 9‐0‐1 Passed ● Rules committee Gino, Kalad, Colin 6‐0‐4 Passed C. Vice President [Atiyeh Samadi] ● D. Associated Students Revelle College Senators ● [Josh Fachtmann] ● [Gino Calavitta] E. Director of Administration [Kasey Ha] ● F. Director of Visibility [Tasha Saengo] ● G. Director of Enterprises [Vacant] ● H. Director of Special Events [Dane Kufa] ● I. Director of Student Services [Jan Natarajan] ● J. Class Representatives ● Senior Class Representative [Ryan Tsu] ● Junior Class Representative [Billy Nguyen] ● Sophomore Class Representative [Jordan Klagenberg] ● Freshman Class Representative [Vacant] ● Freshman Class Representative [Vacant] K. Commuter Representative [Khalid Al-Otoom] ● L. Transfer Representative [Wonhi Lee] ● M. Transfer Representative [Vacant] ● N. Resident Advisor Ex-Officio [Katie Newton] ● O. Revelle College Judicial Board Ex-Officio [Donggun Lee] P. Revelle College Dean of Student Affairs [Dean Sherry Mallory] ● VIII. Committee Reports A. Revelle Organizations Committee [Francesca Lazzaro] ● B. Rules Committee [Soren Nelson] ● C. Appointments Committee [Atiyeh Samadi] ● D. Graduation Committee [Vacant] ● E. -

Bridging the Centuries: the Jewel on the Bay Commemorating the History of the County Administration Center - 2Nd Edition JEWEL on the BAY 2

Bridging the Centuries: The Jewel on the Bay Commemorating the History of the County Administration Center - 2nd Edition JEWEL ON THE BAY 2 Bridging the Centuries: The Jewel on the Bay is the second edition about the history of the San Diego County Administration Center. Beginning in 1902, San Diego’s civic leaders crossed many hurdles before construction could begin on this public building. Bridging the Centuries exam- ines its history and gives us a glimpse into the region at that time. It also commemorates the many San Diegans who held to their vision and overcame numerous obstacles in bringing this grand building to reality. This building’s legacy began in 1938 with its dedication by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The County Administration Center stands as a testa- ment to the strength, vitality, diversity, livability and beauty of this region. This book tells its story. Clerk of the Board of Supervisors, County of San Diego, June 2012 JEWEL ON THE BAY 3 San Diego County Board of Supervisors Greg Cox Dianne Jacob Pam Slater-Price Ron Roberts Bill Horn District 1 District 2 District 3 District 4 District 5 Walter F. Ekard Helen Robbins-Meyer Chief Administrative Assistant Chief Officer Administrative Officer JEWEL ON THE BAY 4 Table of Contents Preface 5 Layout of the grounds 23 Resource Catalog 54 Conception of the Dream 7 The Civic Center becomes the CAC 25 Sources and Locations 54 The Era Preceding Construction 7 The CAC: 1963-1998 25 Available Information 54 Examination of potential construction sites 8 Building expansions -

John and Jane Adams Ephemera Collection MS-0384

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8416zrt No online items John and Jane Adams Ephemera Collection MS-0384 Kira Hall Special Collections & University Archives 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA 92182-8050 [email protected] URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua John and Jane Adams Ephemera MS-0384 1 Collection MS-0384 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & University Archives Title: John and Jane Adams Ephemera Collection Creator: Adams Ephemera Collection (John and Jane Adams Ephemera Collection) Identifier/Call Number: MS-0384 Physical Description: 10.35 Linear Feet Date: 1856-1996 Date (bulk): 1880-1982 Language of Material: English . Scope and Contents The John and Jane Adams Ephemera Collection (1856-1996) offers a glimpse into some of the ways printed materials were used to capture the interest of American culture from the late 1800s through the late 1900s. Such a collection can be used to trace shifts in cultural norms, as these items of ephemera typically reflect the prevailing sentiments of the population for whom the materials were created. The subject matter of the ephemera in this collection varies as wildly as the materials used to create it. The collection has been divided into six series based on subject: Business and Commerce (1880-1982), Political (1903-1996), Travel (1901-1981), Games and Hobbies (ca. 1880's-1942), Religious (1856-1950), and Educational (1907-1935). I. Business and Commerce Inclusive Dates: 1880-1982 Predominant Dates: 1880-1939 The Business and Commerce series predominantly features advertising materials in a variety of formats. While the bulk of these items were manufactured in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of the formats found in this series remain commonplace to American consumer culture, such as brochures, flyers, and business cards. -

San Diego Union-Tribune Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6r29q3mg No online items Guide to the San Diego Union-Tribune Photograph Collection Rebecca Gerber, Therese M. James, Jessica Silver San Diego Historical Society Casa de Balboa 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, Suite 3 San Diego, CA 92101 Phone: (619) 232-6203 URL: http://www.sandiegohistory.org © 2005 San Diego Historical Society. All rights reserved. Guide to the San Diego C2 1 Union-Tribune Photograph Collection Guide to the San Diego Union-Tribune Photograph Collection Collection number: C2 San Diego Historical Society San Diego, California Processed by: Rebecca Gerber, Therese M. James, Jessica Silver Date Completed: July 2005 Encoded by: Therese M. James and Jessica Silver © 2005 San Diego Historical Society. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: San Diego Union-Tribune photograph collection Dates: 1910-1975 Bulk Dates: 1915-1957 Collection number: C2 Creator: San Diego union-tribune Collection Size: 100 linear ft.ca. 150,000 items (glass and film negatives and photographic prints): b&w and color; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Repository: San Diego Historical Society San Diego, California 92138 Abstract: The collection chiefly consists of photographic negatives, photographs, and news clippings of San Diego news events taken by staff photographers of San Diego Union-Tribune and its predecessors, San Diego Union, San Diego Sun, San Diego Evening Tribune, and San Diego Tribune-Sun, which were daily newspapers of San Diego, California, 1910-1974. Physical location: San Diego Historical Society Research Library, Booth Historical Photograph Archives, 1649 El Prado, Casa de Balboa Building, Balboa Park, San Diego, CA 92101 Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open for research. -

ICT Application

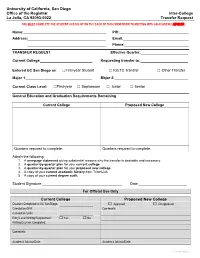

University of California, San Diego Office of the Registrar Inter-College La Jolla, CA 92093-0022 Transfer Request YOU MUST COMPLETE THE STUDENT CHECKLIST ON THE BACK OF THIS FORM PRIOR TO MEETING WITH AN ACADEMIC ADVISOR Name: PID: Address: Email: Phone: TRANSFER REQUEST Effective Quarter: Current College: Requesting transfer to: Entered UC San Diego as: First-year Student IGETC Transfer Other Transfer Major 1: Major 2: Current Class Level: First-year Sophomore Junior Senior General Education and Graduation Requirements Remaining Current College Proposed New College Quarters required to complete: Quarters required to complete: Attach the following: 1. A one-page statement giving substantial reasons why the transfer is desirable and necessary. 2. A quarter-by-quarter plan for your current college. 3. A quarter-by-quarter plan for your proposed new college. 4. A copy of your current academic history from TritonLink. 5. A copy of your current degree audit. Student Signature: Date: For Official Use Only Current College Proposed New College Quarters Completed at UC San Diego: Approved Disapproved Cumulative GPA: Comments: Cumulative Units: Entry Level Writing Requirement: Yes No Writing Courses Completed: Comments: Academic Advisor/Date: Academic Advisor/Date: Revised 4/20/2020 STEP ONE – ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS You must meet the following eligibility requirements to submit an ICT request. If you do not meet one of these requirements, you may not apply for an inter-college transfer. If you entered UC San Diego as a first-year student, the earliest you may apply is during your third quarter of enrollment at your current college. Your request will not be considered until all grades have been posted.