Paper birch Management Guidelines

1) Site Conditions. Paper birch grows reasonably well on a wide variety of sites but its best development is on deep well-drained soils with good fertility, especially sandy loams (podzol or gray-brown and brown podzolic soils), glacial tills and outwash (Burns et al 1990). Paper birch stands in Michigan are commonly found on the habitat types listed in below Table 1. These habitat types are on the lower end of the moisture and nutrient gradients.

Table 1. Common Habitat Types of Aspen in Michigan

NLP1 EUP2 WUP3

s

I

n

i

t

c PArVCo PArV AVb e

r

e

q

a

u

PVE AVVb s

a

i

l

n

i

t

g

y

PArVAa(W) PArV

1. NLP: Northern Lower Peninsula 2. EUP: Eastern Upper Peninsula 3. WUP: Western Upper Peninsula

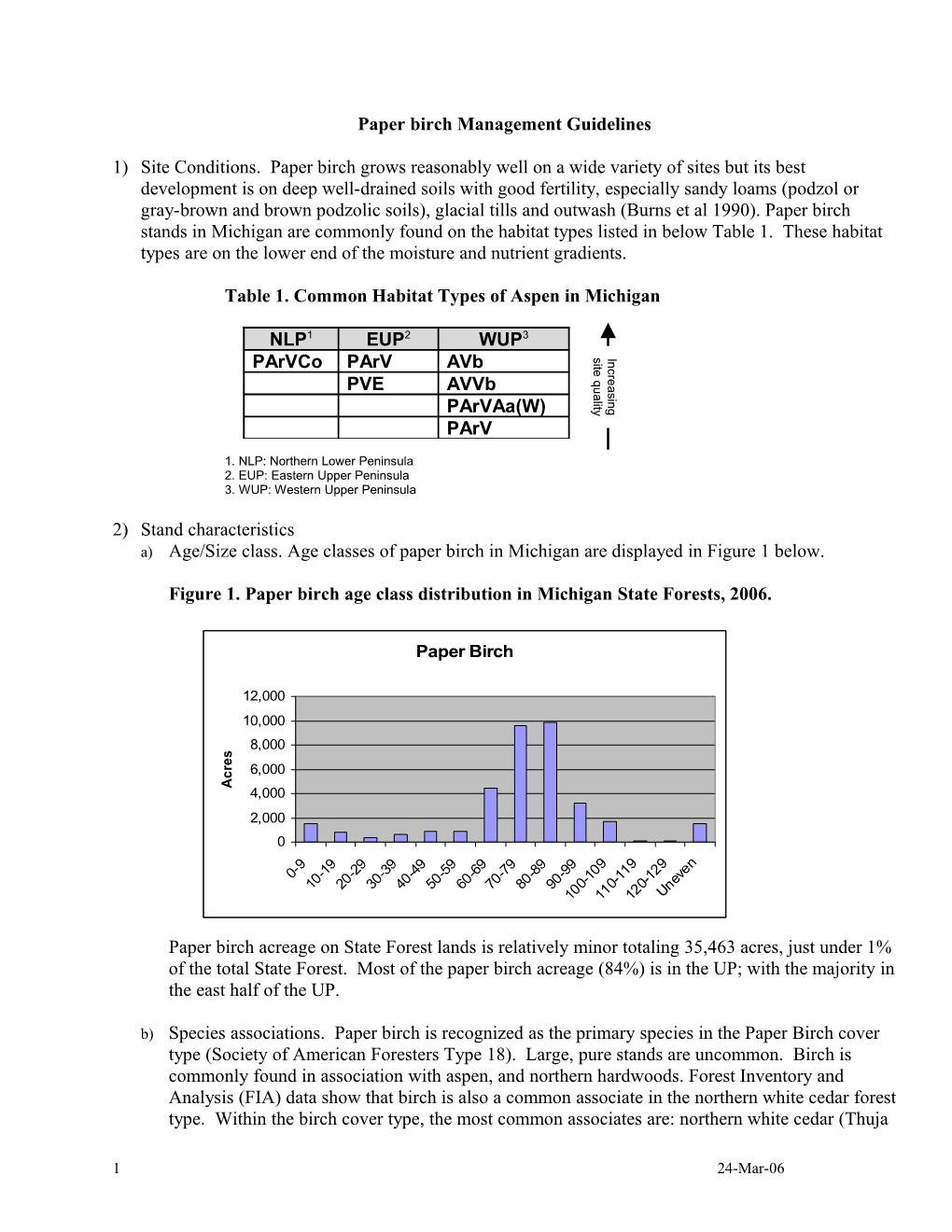

2) Stand characteristics a) Age/Size class. Age classes of paper birch in Michigan are displayed in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Paper birch age class distribution in Michigan State Forests, 2006.

Paper Birch

12,000 10,000 8,000 s e r 6,000 c A 4,000 2,000 0

Paper birch acreage on State Forest lands is relatively minor totaling 35,463 acres, just under 1% of the total State Forest. Most of the paper birch acreage (84%) is in the UP; with the majority in the east half of the UP.

b) Species associations. Paper birch is recognized as the primary species in the Paper Birch cover type (Society of American Foresters Type 18). Large, pure stands are uncommon. Birch is commonly found in association with aspen, and northern hardwoods. Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data show that birch is also a common associate in the northern white cedar forest type. Within the birch cover type, the most common associates are: northern white cedar (Thuja

1 24-Mar-06 occidentalis), red maple (Acer rubrum), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and white spruce (Picea glauca) (Burns and Honkala 1990, WI DNR 2002, FIA 2004).

3) Determining Management Objective. Paper birch is primarily managed on an even-age basis. Birch does not thrive on sites with site indices below 55. These sites should be managed for objectives other than paper birch. Where birch is mixed with aspen or northern hardwoods regenerating birch as the primary cover type will be difficult. Where birch occurs on suitable sites in relatively pure stands some form of shelterwood or seed tree harvest should be used. The following silvicultural recommendations are excerpted or adapted from the Wisconsin DNR Silviculture and Aesthetics Handbook (WI DNR, 2002).

4) Management Recommendations a) Silvicultural System i) Even-age management with regeneration through some form of clearcutting or by the shelterwood system. General thinnings are only necessary to release crop trees for sawlogs (on sites with site index of 70 or more) but can also be done on sites with site index less than 70 if stocking exceeds the A-level (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Stocking Guide for Paper Birch 1 (Marquis et al, 1969) A E R A

L A S A B

TREES PER ACRE

1 The area above the A-level represents overstocked conditions. The area between the A and B-levels represents adequate stocking. The area between the B and C-levels should be considered as slightly understocked because the stand will return to the B-level in 10 years or less. The area below the C-level is definitely understocked. Only trees in the main crown canopy (dominants, co-dominants, and intermediates) should be included in stand measurements to be used with this stocking guide.

2 24-Mar-06 Management Recommendations ii) Seedling/Sapling Stands (0-5" DBH). If the site index is less than 70, allow the stand to develop naturally. When the site index is greater than 70, precommercial thinnings may be done to remove brush and weeds to release crop trees but in most cases it is not recommended. iii) Pole Timber Stands (5-11" DBH). If the stand is at site index rotation age (see Table 2 below), either regenerate to birch or if stand/site conditions are not favorable for birch regeneration convert to another species. If the stand is within 10 years of rotation age or stocking is below the A-level (see Figure 2), no action is required. If the stand is 10 years or more below the rotation age and stocking is at or above the A-level, thin to the B-level. Also when the site index is greater than 70, release crop trees during thinning. iv) Sawtimber Stands (>11" DBH). If stand is at site index rotation age (see Table 2 below), regenerate. When it is below rotation age, treat as recommended for pole stands. v) Regeneration. (1) Seedbed preparation. Scarification or exposure of mineral soil is critical for successful regeneration of paper birch. Disking that incorporates seed and coarse woody debris (CWD) into mineral soil is the best seedbed. Disking should be disked within 2 years of a good seed crop. Partial but not over-toping shade for new seedlings helps protect them from drying without restricting the amount of precipitation that reaches the forest floor (Perala and Alm, 1988). (2) Shelterwood System. The initial cut should be from below to leave 20 to 40 percent crown cover (Perala, 1988). Summer logging is recommended to improve seed bed by scarification and to reduce the sprouting vigor of competing vegetation. Do not cut any aspen during the initial cut to minimize sprouting competition. Remove the overstory two to four years after the initial cut when seedlings are about waist height. This final cut should be done in winter to minimize damage to paper birch seedlings and sprouts. (3) Patch Clearcuts. Clearcutting small irregularly shaped patches of less than one acre is especially useful on small tracts, roadsides, parks, or any area where consideration of available space or potentially adverse aesthetic impact is important. Summer logging is recommended and residual stems should be cut concurrently. Late summer or fall scarification might be needed also. (4) Clearcuts. This technique is recommended only when other regeneration techniques are unfeasible for reasons such as terrain, geographic layout, merchantability, operability, etc. Regeneration will be from stump sprouts and seed. Winter cutting, after fall seed dispersal, may be desired. Three to five trees per acre should be left as a seed source if cutting is done before seed dispersal. NOTE: In a clearcut, factors influencing regeneration may favor species other than paper birch, thereby causing natural conversion.

3 24-Mar-06 Table 2. Expected rotation ages and sizes for paper birch stands (adapted from Marquis et al, 1969)

Species and objective Paper birch site index Average diameter2 Age (feet) (inches) (years) Paper birch sawtimber 50 9 75 60 10 70 70 11 65 Paper birch, boltwood 50 8 65 60 9 60 70 9 45 Paper birch, aesthetics 80 2. Average diameter of species shown, not of the entire stand

5) Wildlife considerations. A science-based, landscape level approach should be used to identify where we want to manage for birch cover types, using tools such as: ecological classification systems like habitat type (Burger and Kotar, 2003) or other systems, ecoregional plans, MI WILD, and stream classification systems. Historic and current cover types should also be considered in the decision making process.

Birch management requires both a “top down” (landscape) and “bottoms up” (stand level) approach to management. Planning activities should focus on how much land is suitable for birch management, and where that management should occur. Stand level decisions are also critical, as these small units make up communities and landscapes. What is done at the stand level effects wildlife habitat. Wildlife is impacted by both the composition and structural components of stands. The more diverse the stand, the more diverse the array of wildlife species using the stand. Although birch has a relatively limited distribution and its history is closely related to fire history it should be managed on a variety of sites where possible. Harvest should replicate natural disturbance patterns as much as possible, allowing for a variety of stand shapes, sizes, and amounts of variable retention. Prescribed fire may be used to control competing vegetation and prepare a suitable seedbed for birch establishment. On these sites, an array of age classes should exist representing everything from newly regenerated to old and decadent. Rotation ages on this cover type should range from 45 to 80 years. Management specifications should vary from site to site. Pure birch stands are less likely in the future in the absence of hot, catastrophic fire so birch will be found in mixtures with other species like aspen, spruce-fir and northern hardwoods. Birch as a component of other timber types is very important and should be retained as a minor associate as much as possible.

Birch is an important component of wildlife habitat affecting many species. All life stages are of value to wildlife. It is generally believed that there is relatively low wildlife species diversity in pure birch stands as opposed to more mixed stands. In Michigan, at least 60 species of birds and over 111 plant species are associated with birch.

Early developmental stages are important to a wide array of game animals (white-tailed deer, american woodcock, snowshoe hare), and non-game species as well (chestnut-sided warbler, morning warbler). Late developmental stages provide habitat for species such as the red-eyed vireo and Connecticut warbler. Dead and down birch provides habitat to amphibian species.

4 24-Mar-06 Some areas of birch habitat should be set aside as “Special Conservation Areas” where natural processes are allowed to occur with minimal interference. Ultimately, these areas will likely convert to other cover types.

“Variable retention” harvests are useful in promoting wildlife values, as well as aesthetic values when birch stands are treated. Specific site conditions dictate possible candidates for retention. Promoting a conifer component enhances diversity, with common species including red pine, white pine, balsam fir, northern white-cedar, and eastern hemlock. Deciduous species often include various oaks, as well as white birch, red maple, sugar maple, and others. Leave trees occur as individual trees or groups of trees. Even mature birch trees are beneficial when retained in “clumps” of other trees species, around the edges of forest openings, and along stand edges. Mature birch legacy trees ultimately provide snags that get used by woodpeckers and secondary nesters, and then eventually become coarse woody debris. While legacy trees are not long lived, they are an essential attribute in cover types that are predominately dominated by young age classes. The wildlife values associated with variable retention are many. They vary from providing mast, to thermal cover for ungulates, to perches for various species of birds that would not otherwise be found in these stands. Since birch is most commonly managed on an “even-aged” basis, variable retention can go along way towards alleviating public concern regarding clearcutting.

Finally, fisheries resources need to be considered in managing birch. This is particularly true of cold water streams. Birch management in riparian zones can have a major impact on fisheries. Birch management in riparian zones can increase available habitat for beaver, at the expense of trout populations. Fisheries managers often prefer shade tolerant, long-lived forest cover in these areas to provide shade to keep stream temperatures cooler and to attempt to discourage beaver. Effective communication among resource managers is critical in these areas so that numerous conservation values are given appropriate consideration.

Damage due to wildlife usage has been documented in this timber type. Ungulates, as well as beaver, can have an impact on this resource.

6) Biodiversity considerations. When planning timber harvests in birch, consider designating 3 to 5% of the total stocking as potential cavity trees and a source of future snags. Retain a minimum of four secure cavity or snag trees per acre, with one exceeding 24” dbh and three exceeding 14” dbh. In areas lacking cavity trees, retain live trees of these diameters with defects likely to lead to cavity formation. Trees reserved for cavity trees and future snags can be seed trees or overstory trees left for shelterwood purposes. In final harvest situations, consider leaving uncut patches within and along the edges of the harvest area. These should utilize naturally occurring features of the stand like conifer pockets, poorly drained swales and patches of mast producing species like oak, cherry or beech. Patches may be left on the edges or within the harvest area. For harvest areas greater than 10 acres that are more than 5 chains wide some of the patches should be left within the harvest area. Patches of at least ¼ ac (120 ft dia) should be left to equal at least 5% of the area. Use cavity trees exceeding 18” dbh or active den trees as nuclei for uncut patches. During harvest, avoid damaging existing downed woody material, especially large (16”+) hollow logs and stumps. Leave downed woody material on site after harvest operations when possible. If snags and cavity trees pose safety hazards they should be marked so that woods workers can avoid them. OSHA standards require that “danger trees” are to be felled or marked so that no work is conducted within two tree lengths of them. Therefore, it is often better to leave clumps or groups of trees for biodiversity and wildlife

5 24-Mar-06 purposes rather than individual trees. If snags must be felled for safety reasons they should be left where they fall (adapted from Flatebo et al, 1999).

Several plants of special concern occur in these communities such as heart-leaved amica, sweet cicely, fairy bells, and rayless mountain ragwort. Animal species of concern include red-shouldered hawk, and northern goshawk. Consult MNFI conservation management guidelines: for plants: http://web4.msue.msu.edu/mnfi/data/specialplants.cfm for animals: http://web4.msue.msu.edu/mnfi/data/specialanimals.cfm

[Keith, the preceding wildlife and biodiversity sections were adapted from Mike Koss’ aspen write up and need to be revised to apply to birch. I did a search and replace to change “aspen” to “birch” and added the bit about fire and shelterwood but the rest of it is pretty much untouched. Please revise as needed.]

7) Regeneration standards. For purposes of MDNR’s regeneration survey, paper birch stands are considered to be adequately stocked with 1,200 stems per acre over 1 ft tall at age 42.

8) Forest Health considerations. Paper birch is subject to many of the same insect and disease pests that attack other shade-intolerant hardwoods in the Lake States, including gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar), forest tent caterpillar (Malacasoma disstria), saddled prominent (Heterocampa guttivitta), birch sawflies (Heterarthrus nemoratus) and birch leafminer (Fenusa pusilla). These insects rarely cause mortality of otherwise healthy paper birch. Repeated attacks by birch leafminer can predispose trees to attack by the bronze birch borer. Larval feeding by the bronze birch borer interferes with transport of sugars and other photosynthates from leaves to roots. This leads to smaller, less dense root systems that cannot provide adequate water to the crown. Top-down crown dieback can eventually occur. Particularly in trees suffering from drought stress.

Paper birch is subject to a number of fungal organisms that enter through wounds and branch stubs to cause discoloration and decay. Principal decay-causing fungi include Inonotus obliqua and Phellinus igniarius. The root-rotting fungus Armillaria mellea infects paper birch, causing cracks at the base of the stem (‘collar crack’).

Since the early 1930’s, widespread birch decline has occurred periodically across eastern Canada and the northeast United States. Birch decline is the deterioration and mortality of white and yellow birch usually following harvesting or other site disturbance, and is characterized by small, yellow leaves in the upper crown, twig and branch dieback, bud failure and tree death within 3 to 6 years. The problem is not fully understood, but predisposing stressors like drought, the birch leafminer/bronze birch borer complex, root mortality and possibly viral agents play a role.

It is important to remember that paper birch is a shallow-rooted species and very susceptible to even slight increases in soil temperature. Silvicultural activities should: Protect root systems of residual birch from damage and excessive sunlight Remove overmature and declining birch Remove shelterwood overstories as soon as understory birch is established.

9) References

2 Adapted from Cayuga Project Final Environmental Impact Statement, Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, 2003. http://www.fs.fed.us/r9/cnnf/natres/eis/gd/cayuga/ 6 24-Mar-06 a) Burns, Russell M and Barbara H. Honkala. 1990. Silvics of North America. USDA For Serv Ag Handbook 654. b) FIA 2004. Miles, Patrick D. Mar-20-2006. Forest inventory mapmaker web-application version 2.1. St. Paul, MN: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station. www.ncrs2.fs.fed.us/4801/fiadb/index.htm c) Marquis, D. A, Dale S. Solomon, John C. Bjorkbom, 1969. A Silvicultural Guide for Paper Birch in the Northeast. USDA For Serv, NEFES Res paper NE-130. d) Perala, D. A., and A. A. Alm. 1988. Regenerating paper birch in the Lake States with the shelterwood method. Northern J. Applied Forestry., vol. 6, no. 4, p. 151-153. e) WI DNR, 2002, Silviculture Handbook 2431.5, Ch 44. http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/land/forestry/Publications/Handbooks/24315/

7 24-Mar-06