Guatemala's trash 'miners' risk lives to find gold

By ALBERTO ARCE - Associated Press | AP

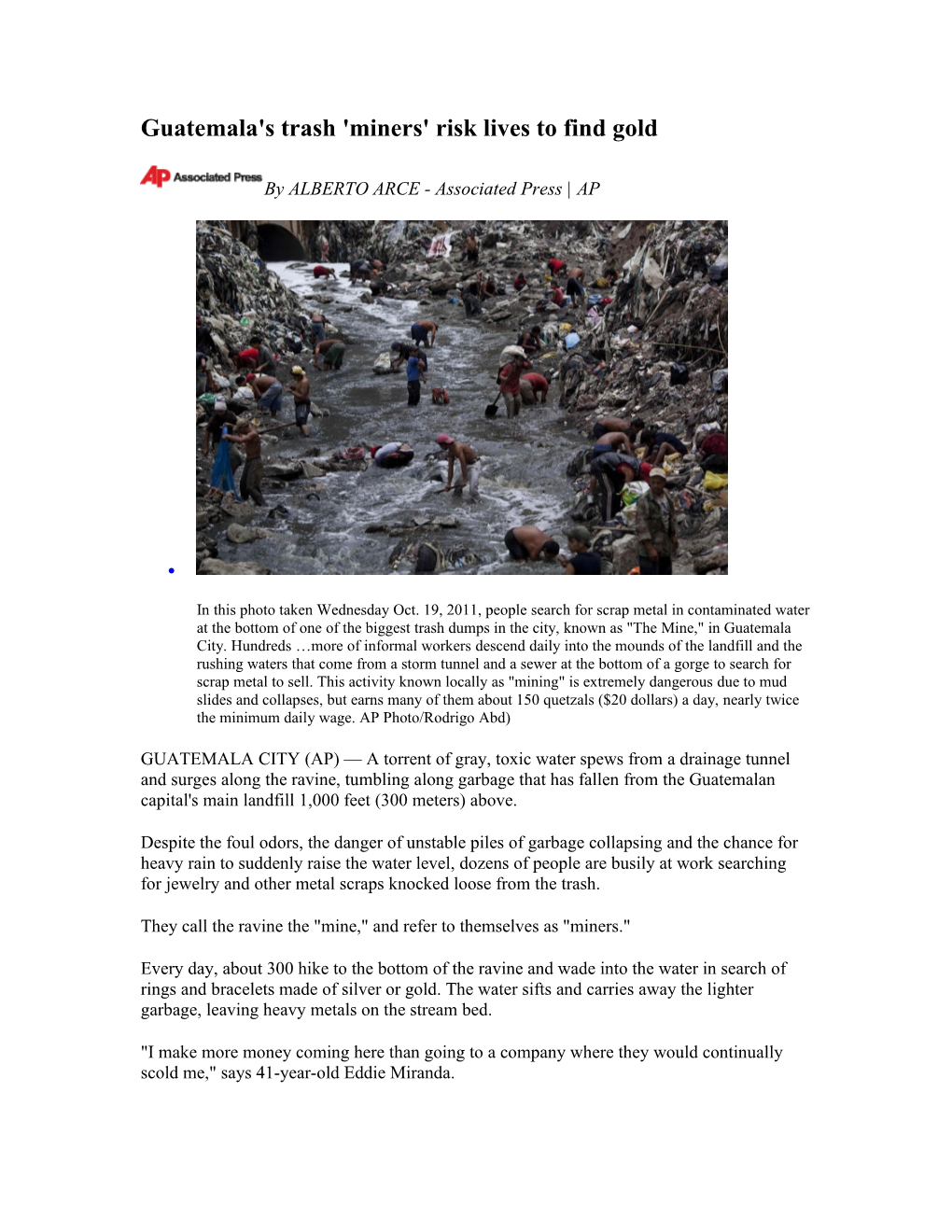

In this photo taken Wednesday Oct. 19, 2011, people search for scrap metal in contaminated water at the bottom of one of the biggest trash dumps in the city, known as "The Mine," in Guatemala City. Hundreds …more of informal workers descend daily into the mounds of the landfill and the rushing waters that come from a storm tunnel and a sewer at the bottom of a gorge to search for scrap metal to sell. This activity known locally as "mining" is extremely dangerous due to mud slides and collapses, but earns many of them about 150 quetzals ($20 dollars) a day, nearly twice the minimum daily wage. AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

GUATEMALA CITY (AP) — A torrent of gray, toxic water spews from a drainage tunnel and surges along the ravine, tumbling along garbage that has fallen from the Guatemalan capital's main landfill 1,000 feet (300 meters) above.

Despite the foul odors, the danger of unstable piles of garbage collapsing and the chance for heavy rain to suddenly raise the water level, dozens of people are busily at work searching for jewelry and other metal scraps knocked loose from the trash.

They call the ravine the "mine," and refer to themselves as "miners."

Every day, about 300 hike to the bottom of the ravine and wade into the water in search of rings and bracelets made of silver or gold. The water sifts and carries away the lighter garbage, leaving heavy metals on the stream bed.

"I make more money coming here than going to a company where they would continually scold me," says 41-year-old Eddie Miranda. He says he finds scraps worth 150 quetzals, or $20, almost every day.

He got lucky on a recent day. "I found a bracelet with 9 grams (0.32 avoir ounces) of gold. I got 2,000 quetzals ($256) for it."

It may not seem like much, but it's almost as much as the monthly $270 minimum wage in this Central American nation.

At dawn, the scavengers arrive much as if coming to a regular work place. Many are wearing clean, ironed shirts and even whistling. They carry shovels and backpacks filled with their garbage bags, snacks and change of clothes. They leave their dry clothes at an improvised camp and start looking for treasures.

Scavenging, which is prohibited by the government, can get particularly dangerous during storm season. The workers say many have died while trying to pick garbage out of water raging through the ravine.

Dozens perished one day in 2008 when a mountain of garbage collapsed on them.

"The piles of rubbish and dirt bounced off the bottom of the river and dragged me while I was trying to escape," said Antonio Yupe, 32, a scavenger who survived the disaster. "I took a lot of spins. I broke my leg. I don't know how, but I was buried with my face uncovered, so I could breathe until I was rescued."

Still, the "miners" call the dangerous heavy rain "the blessing of winter," because the increased flow of water improves their chances of finding more metal.

If the scavengers don't find jewelry, they collect screws, faucets and other recyclable metal items that they can sell for 85 cents a pound. That amounts to twice the minimum wage for an average trip.

A few yards (meters) from the mouth of the tunnel, 35-year-old Avelino Perez and 19-year- old Julio Leja are up to their necks in water, surrounded by towering mounds of garbage. They push their shovels down into the current to bring up scrap metal, food containers and other objects.

Perez seems happy. He shows off a dirty Roman Catholic cross he has plucked from the bottom. His fingers look burned with acid and his nails are yellow. But he smiles.

"It's gold. I may get 500 quetzals ($65) for it."

ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS ON YOUR WARMUP:

1. What is the attraction to these dumps? 2. Describe the dangers that these “miners” have to deal with. 3. List some of the “valuables” that have been found. 4. Does this type of activity help or hurt the local Guatemalan community and economy? Explain.