Another coinage If you love your family, go out and get a job – on the other side of the world. Jeremy Seabrook looks at what globalization is doing to intimate human bonds.

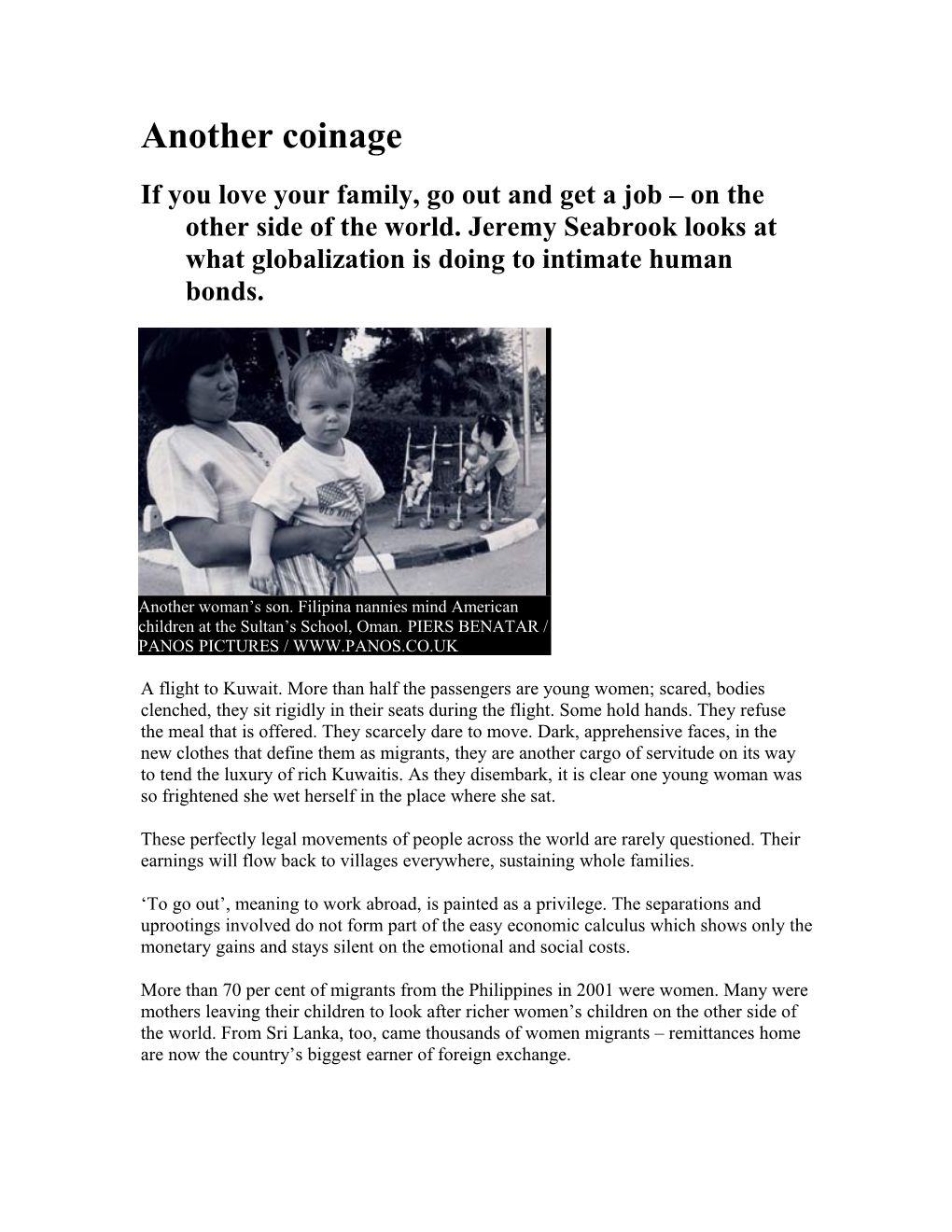

Another woman’s son. Filipina nannies mind American children at the Sultan’s School, Oman. PIERS BENATAR / PANOS PICTURES / WWW.PANOS.CO.UK

A flight to Kuwait. More than half the passengers are young women; scared, bodies clenched, they sit rigidly in their seats during the flight. Some hold hands. They refuse the meal that is offered. They scarcely dare to move. Dark, apprehensive faces, in the new clothes that define them as migrants, they are another cargo of servitude on its way to tend the luxury of rich Kuwaitis. As they disembark, it is clear one young woman was so frightened she wet herself in the place where she sat.

These perfectly legal movements of people across the world are rarely questioned. Their earnings will flow back to villages everywhere, sustaining whole families.

‘To go out’, meaning to work abroad, is painted as a privilege. The separations and uprootings involved do not form part of the easy economic calculus which shows only the monetary gains and stays silent on the emotional and social costs.

More than 70 per cent of migrants from the Philippines in 2001 were women. Many were mothers leaving their children to look after richer women’s children on the other side of the world. From Sri Lanka, too, came thousands of women migrants – remittances home are now the country’s biggest earner of foreign exchange. According to migrant activist Irene Fernandez such workers are: ‘women of love because they leave behind their own families to ensure a better economic future for them, and go to another country to care for another family.’

In the cancer wards of Seattle and Atlanta, in the nursing homes and geriatric wards of Frankfurt and Lyon, the frail and infirm are bathed and nursed by the tenderness of hands roughened by work as children in fields and farms; recruited and seduced by the promises of labour, the privilege of cleaning up the incontinence of the very old.

The trade in humans The world has woken up to the major industry of trafficking in women, the clandestine and industrialized trade in persons. This is less because of the abhorrence which this inspires in the rich and powerful, but rather because of its very closeness to the acceptable, ordinary contracts drawn up by agents and entrepreneurs routinely exporting, trading and dealing in human beings.

There is a fine, scarcely distinguishable, line between village girls forced into bondage by unrepayable debts and sent secretly to the closed brothels and sex parlours of the West, and the labour recruitment agencies, those Western government-inspired poachers of medical staff snatching desperately needed women from the overcrowded hospital wards in the South.

The middle-people in these dealings, the recruiters and job-placement agencies, impound the passports of the workers they place, charge excessive fees and provide loans at exorbitant interest that will have to be paid back from future earnings.

Behind all the people, whether recruited, cheated or cozened into leaving home for the sake of a ‘better life’, lie shattered landscapes, broken webs of connectedness, the most bitter separations and reluctant partings, the loss of loved flesh and blood in the places where they are most needed.

These are not idle reckonings, although they are excluded from the balance sheets which show only the gains and profits made out of trafficking, legal and prohibited.

Who has ever been able to account for the effects on the children deprived of parents by economic necessity? Where are the assessments of the damage to those to whom the absences appear as desertions, and for whom the consolations – the VCR, the giant teddy- bear, the Walkman and the computer – must stand in the place of the missing parents?

The money keeps coming, but the affection must be compressed into the hurried telephone call or sublimated in the glittering presents at Christmas or Eid, festivals unrecognized by employers. The compensations come to be more tangible, more reliable than the intermittent relationships between mothers and children; and these unrecorded disruptions are paid for later, in another coinage. Boys seek solace in gang relationships, sniffing at the fumes above the flame beneath the square of silver foil on the waste- ground; girls get pregnant at 15. ‘The pain is always there,’ says Renu, from Bangladesh, who worked as a domestic servant for a good employer in Malaysia. ‘My daughter became sterile as a result of an untreated infection of the ovaries. This might have happened even if I had been there, but I felt it was my fault; it was punishment for my absence.’

The wages are paid, the contract finished, the labour forgotten; only the effects live on, passed down to a new generation.

Meanwhile another woman is on her way to a strange new ‘home’ in the rich world. Bridget Anderson quotes a Filipina working as a servant in Athens. She observed that when the children were playing at families, they would say:

‘He is the Daddy, I am the Mummy, and she is the Filipina.’

As women in the richer world have been liberated from caring work in the family – work their menfolk never felt bound to do – that labour has not gone away: it has simply been contracted out.

‘She is like my daughter,’ say the owners of a live-in servant, who works up to 18 hours a day.

Rarely are domestic servants heard to say of their mistresses: ‘She is like my mother.’