Music, Longing and Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Com.Stampa GOGOL BORDELLO @ Meeting Del Mare 2014

COMUNICATO STAMPA Si terrà dal 30 maggio all’1 giugno a Marina di Camerota (SA) la XVIII edizione del Meeting del Mare . Il festival ideato e diretto da don Gianni Citro , nato nel 1997, nel corso di questi anni ha ospitato grandi nomi della musica italiana: Vinicio Capossela, Franco Battiato, Piero Pelù, Subsonica, Caparezza, Afterhours, Elio e le storie tese, Morgan, Baustelle, Roy Paci, solo per citarne alcuni. Adesso, raggiunta la maggiore età, si regala una band internazionale dal grande impatto live, molto amata in Italia. Saranno infatti i GOGOL BORDELLO gli headliner della terza serata, in programma domenica 1 giugno al porto della cittadina cilentana (ingresso gratuito). Il travolgente combo gipsy-punk guidato da Eugene Hutz torna nel nostro paese per tre date – oltre al Meeting del Mare si esibiranno anche a Bologna (Rock in Idro, 31 maggio) e Milano (Carroponte, 4 giugno) – con il loro euforico show a seguito della pubblicazione dell’ultimo lavoro discografico “Pura Vida Conspiracy ”. Pubblicato lo scorso luglio per l’etichetta ATO Records/Casa Gogol Records, l’album è stato registrato in Texas ai Sonic Ranch Studio di El Paso e prodotto da Andrew Scheps . 12 tracce che seguono la scia dei precedenti lavori, su tutti “ Gypsy Punks: Underdog World Strike ” (2005, prodotto da Steve Albini ), “Super Taranta! ” (2007, prodotto da Victor Van Vugt ) e “ Trans- Continental Hustle ” (2010, prodotto da Rick Rubin ). Quello di Marina di Camerota si annuncia come uno concerto dirompente ed energico, tutto da ballare in riva al mare sulle note della patchanka musicale tipica di questa incredibile formazione e del suo carismatico leader. -

Eugene Hutz Interview

4 FEATURE FOLK ON THE EDGE As Gogol Bordello returns to Australia, singer Eugene Hutz warns a musical storm is coming, writes Jane Cornwell fter three decades in the rock busi- ness, Eugene Hutz knows how to make an entrance. I’m waiting in the mezzanine lounge of a west London hotel popular with music- Aians, nodding along to an 1980s chart hit sound- track, when the lanky, long-haired frontman suddenly appears at the top of the stairs, strum- ming a beat-up Cordoba acoustic and looking, as they say in Britain, the dog’s bollocks. He’s wearing a bomber jacket, a looped patterned scarf, a single gold hoop earring and a clutch of long gold necklaces; his tight black trousers have large white termites printed on them. His cheekbones are sharp, his eyes cobalt blue. His handlebar moustache curls at the corners. A man without a moustache is like a woman with one, goes an old Ukrainian saying that Hutz, who is Ukrainian, has confessed to making up. “Hallo,” he says in his thick Slavic-American accent, percussively slapping the body of his guitar, which is plastered in oval-shaped car stickers from Spain, Mexico, Britain, all over. “So it is you who will tell them we are coming.” Gogol Bordello was last in Australia in 2010 storytelling. With all the illegitimate hierarch- try blues, Brazilian carnival music and keening Eugene Hutz but the memories of the band’s frenzied, mosh- ical things going on in society all the time, this folk melodies from eastern Europe. Two female channels his pit-tastic shows linger on in the minds of those feeling of all-inclusiveness is very healing for backing vocalists will whoop and high-kick. -

FILTH and WISDOM Panorama FILTH and WISDOM Special FILTH and WISDOM Regie: Madonna

PS_4503:PS_ 24.01.2008 18:52 Uhr Seite 150 Berlinale 2008 FILTH AND WISDOM Panorama FILTH AND WISDOM Special FILTH AND WISDOM Regie: Madonna Großbritannien 2008 Darsteller A. K. Eugene Hutz Länge 81 Min. Holly Holly Weston Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Juliette Vicky McClure Farbe Professor Flynn Richard E. Grant Harry Beechman Stephen Graham Stabliste Sardeep Inder Manocha Buch Madonna Sardeeps Frau Shobu Kapoor Dan Cadan Geschäftsmann Elliot Levey Kamera Tim Maurice Jones Francine Francesca Kingdon Kameraführung Peter Wignall Chloe Clare Wilkie Schnitt Russell Icke Frau des Ton Simon Hayes Geschäftsmanns Hannah Walters Choreografie Stephanie Roos DJ Ade Tiffany Olson Lorcan O’Neill Guy Henry Production Design Gideon Ponte Nunzio Nunzio Palmara Art Director Max Bellhouse Kostüm B Maske Sinden Dean Regieassistenz Tony Fernandes Casting Dan Hubbard Eugene Hutz Produktionsltg. Sue Hiller Aufnahmeleitung Gavin Milligan FILTH AND WISDOM Produzentin Nicola Doring Executive Producer Madonna Andriy Krystiyan, abgekürzt A. K., ist aus der Ukraine nach England immi- Associate Producer Angela Becker griert. A. K. ist Philosoph, das behauptet er jedenfalls, außerdem Dichter Co-Produktion HSI London, London und eine Autorität in allen Fragen des Lebens. Zugleich verfolgt er den Plan, ein Weltstar zu werden – „global superstardom“ nennt A. K. das Ziel, das er Produktion und seine Band Gogol Bordello mit ihrem heftigen Zigeuner-Punk anpeilen. Semtex Film 72-74 Dean Street Um bis dahin über die Runden zu kommen, lässt sich A. K. einstweilen für GB-London W1D 3SG Rollenspiele vor verheirateten Männern engagieren und tritt dabei in Frau - Tel.: +44 20 74 37 33 44 en kleidern auf. -

The Pied Piper of Hutzovina

THE PIED PIPER OF HUTZOVINA 65 minutes, 2006, UK Director: Pavla Fleisher Cast: Eugene Hutz, Boban Markovic, Zita Synopsis In the summer of 2004, on a car journey in Eastern Europe, Pavla Fleischer met and fell in love with Eugene Hutz, lead singer of New York's Gypsy Punk band Gogol Bordello. Captivated by his energy and his musical verve, and desperate to get to know him better, she decided to make a film about him. The Pied Piper of Hutzovina follows Eugene and Pavla on their subsequent road trip through Eugene's home country, Ukraine. It is the story of two people travelling together on two very different courses. Her aim is to rediscover a forgotten romance; his is to rediscover his roots. She hopes to find love on the road; he hopes to find musical inspiration from the gypsy culture he is determined to preserve. This is an intimate portrait of a filmmaker with a passion for her subject, and a punk musician with a longing to revisit his past. Theirs is a journey which tests their relationship and challenges their perceptions of the music they both love. Review, Nora Lee Mandel, Film-Forward.com Before the entertaining and charismatic Eugene Hütz danced with Madonna to a worldwide audience for Live Earth, and his exuberant Gypsy punk band Gogol Bordello played festivals from Glastonbury to Madison Square Garden, he flirted with London-based filmmaker Pavla Fleischer, caught on video when she was visiting her home town of Prague as he serenaded her with his beloved songs of the Roma people. -

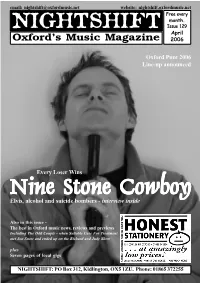

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 129 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Oxford Punt 2006 Line-up announced Every Loser Wins NineNineNine StoneStoneStone CoCoCowbowbowboyyy Elvis, alcohol and suicide bombers - interview inside Also in this issue - The best in Oxford music news, reviews and previews Including The Odd Couple - when Suitable Case For Treatment met Jon Snow and ended up on the Richard and Judy Show plus Seven pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Harlette Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] PUNT LINE-UP ANNOUNCED The line-up for this year’s Oxford featured a sold-out show from Fell Punt has been finalised. The Punt, City Girl. now in its ninth year, is a one-night This years line up is: showcase of the best new unsigned BORDERS: Ally Craig and bands in Oxfordshire and takes Rebecca Mosley place on Wednesday 10th May. JONGLEURS: Witches, Xmas The event features nineteen acts Lights and The Keyboard Choir. across six venues in Oxford city THE PURPLE TURTLE: Mark and post-rock is featured across showcase of new musical talent in centre, starting at 6.15pm at Crozer, Dusty Sound System and what is one of the strongest Punt the county. In the meantime there Borders bookshop in Magdalen Where I’m Calling From. line-ups ever, showing the quality are a limited number of all-venue Street before heading off to THE CITY TAVERN: Shirley, of new music coming out of Oxford Punt Passes available, priced at £7, Jongleurs, The Purple Turtle, The Sow and The Joff Winks Band. -

Sacro E Profano (Filth and Wisdom)

NANNI MORETTI presenta SACRO E PROFANO (FILTH AND WISDOM) un film di MADONNA USCITA 12 GIUGNO 2009 Ufficio stampa: Valentina Guidi tel. 335.6887778 – [email protected] Mario Locurcio tel. 335.8383364 – [email protected] www.guidilocurcio.it SACRO E PROFANO (Filth and Wisdom) Un film di Madonna Scritto da Madonna & Dan Cadan Produttore esecutivo Madonna Prodotto da Nicola Doring Produttore associato Angela Becker Fotografia Tim Maurice Jones Montaggio Russell Icke Scene Gideon Ponte Costumi B. PERSONAGGI E INTERPRETI A.K. Eugene Hutz Holly Holly Weston Juliette Vicky McClure Professor Flynn Richard E. Grant Sardeep Inder Manocha Uomo d'affari Elliot Levey Francine Francesca Kingdon Chloe Clare Wilkie Harry Beechman Stephen Graham Moglie dell'uomo d'affari Hannah Walters Moglie di Sardeep Shobu Kapoor DJ Ade Lorcan O’Niell Guy Henry Nunzio Nunzio Palmara Mr Frisk Tim Wallers Padre di A.K. Olegar Fedorov Giovane A.K. Luca Surguladze Mikey Steve Allen Durata: 80’ I materiali stampa sono disponibili sul sito www.guidilocurcio.it 2 SACRO E PROFANO (Filth and Wisdom) SINOSSI A.K. (Eugene Hutz) è un musicista costretto a soddisfare i fantasmi sadomaso dei suoi clienti per poter finanziare le prove del suo gruppo punk-gitano. Juliette (Vicky McClure) lavora in farmacia ma sogna di fare la volontaria in Africa. Holly (Holly Weston) è una ballerina classica che, per pagare l'affitto, inizia una carriera inaspettatamente brillante come lap dancer. Attorno a loro una Londra colorata, multietnica, abitata da personaggi folkloristici. Un film eccentrico, ironico, che racconta storie uniche e universali attraverso la vita quotidiana - buffa, a volte tragica, ma sempre terribilmente autentica - dei suoi protagonisti. -

Gogol Bordello in Concerto Ad Orvieto. Sonorità Irriverenti E Gypsy Punk Pubblicato Su Gothicnetwork.Org (

Gogol Bordello in concerto ad Orvieto. Sonorità irriverenti e Gypsy punk Pubblicato su gothicNetwork.org (http://www.gothicnetwork.org) Gogol Bordello in concerto ad Orvieto. Sonorità irriverenti e Gypsy punk Articolo di: Giovanni Battaglia [1] “L’irriverente band del carismatico Eugene Hütz porterà la tipica debauchery dei loro live set direttamente sul palco di Umbria Folk Festival…e le sorprese non mancheranno di certo...”. Così iniziava la presentazione sul sito internet del magnifico concerto dei Gogol Bordello che si è svolto a chiusura della manifestazione “Umbria Folk Festival” martedì 24 agosto 2010. E le sorprese non sono mancate, innanzitutto per lo straordinario impatto live di quella che sicuramente è una delle band più divertenti del momento e che ha dato vita ad un concerto memorabile; in secondo luogo per la tristissima polemica in seguito alla bestemmia di Eugene Hütz durante la canzone “Santa Marinella”. La canzone dello scandalo era già conosciuta perché pubblicata alcuni anni fa sul disco Gypsy Punk e parla del soggiorno forzato in Italia di Eugene Hütz mentre stava attendendo la cittadinanza americana. Non si riesce quindi a capire di che cosa si lamenti l’assessore alla cultura di Orvieto che non ha perso un secondo per diramare un comunicato stampa nel quale prende le distanze dalla manifestazione e dalle gravi offese arrecate al sentimento religioso dalla band. Inoltre (udite, udite), si è riservato di querelare i Gogol Bordello definendoli assolutamente incompatibili con i sentimenti religiosi della popolazione. Premesso che la bestemmia mi sembra un modo infelice ed irrazionale di sfogare la propria rabbia e che io non sono un bestemmiatore, non riesco a capire come la stessa possa offendere lo spirito religioso che dovrebbe volare un po’ più in alto di queste meschinità. -

“Gypsy Punks”: the Performance of Real and Imagined Cultural Identities Within a Transnational Migrant Group

Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 24, Issue 1, Pages 3–24 Russian Jews and “Gypsy Punks”: The Performance of Real and Imagined Cultural Identities within a Transnational Migrant Group Rebecca Jablonsky New York University Introduction This article will discuss the implications of the construction of cultural space among Russian Jews in New York City and the narratives employed to collectively produce and claim this space, particularly the repeated notion of being without a “home” or “place.” Analysis of these narratives will address the uniqueness of Russian Jewish identity and the historical factors that contributed to the isolation of Russian Jews in their homeland and in New York.Special attention will be paid to physical Russian Jewish spaces, considering these spaces as mediating agents in constructing cultural identity, as well the role of the music scene as it relates to cultural cohesion. This focus is drawn from communications scholar David Morley’s assertion that media technologies tend to “transport the individual or small family group to destinations (physical, symbolic or imaginary) well beyond the confines of home or neighborhood, combining privacy with mobility” (149). Considering Russian Jews as a highly mobile group that centers on the exclusion of others, inclusion manifests itself through the construction of, and participation in, spaces that represent their physical and imagined communities. Using historical and theoretical research, a literature review, ethnographic techniques, interviews, analyses of songs and media, and the presentation of personally recorded media, Russian Jewish identity and alienation will be used as a means of understanding the “gypsy punk” movement that has emerged in the popular New York City nightclub, Mehanata, also known as “The Bulgarian Bar.” The rising fame of the self- proclaimed gypsy punk band Gogol Bordello will be considered, along with the textual, audio, and visual media that presents this scene to participants. -

Footbal Victory Over Rochester, See Page 6! University Closes Multiple Satellite Libraries

94 Years as CUA‘s Primary News Source 94TH YEAR , ISSUE NO. 1 Friday, September 16 , 2016 CUATOWER .COM Footbal Victory over Rochester, See Page 6! University Closes Multiple Satellite Libraries By AN GEL I CA SI SSO N Libraries System according Tower Staff to Stephen Connaghan, the University Librarian. Early in the Fall 2016 “Operating the semester it was announced small branch locations is that the Architecture and costly when compared Planning library located in against the measurable the Crough building would metrics of attendance close. Earlier this summer it and circulation,” said was also announced that the Connaghan. “Maintaining Physics library in Hannan good service schedules Hall would be closed. while still protecting the The collections of both collections requires a lot libraries are currently being of man-hours by our full- integrated into the stacks of time staff & trained student COURTESY OF CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY Mullen Library. employees.” Freshmen Class of 2020 following Convocation in Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Financial reasons Staff in the Physics Conception. and concerns of efficiency library said that while the prompted these changes in the Catholic University See Libraries, page 4 President Garvey Welcomes Class of 2020 at Freshman Convocation Center for Cultural administration. At the were finished processing By ALEXA N DER SA N TA N A Engagement Opens in Tower Staff convocation, the members the administration and of the Class of 2020 each faculty processed to the Pryzbyla Center received a university pin and front of the Basilica. They On Wednesday, heard remarks from various followed University September 14, 2016, The held in its new office in the members of the university Marshall Thérèse-Anne By EMMR I CK MCCADDE N Catholic University of Pryzbyla Center. -

Working Copy.Indd

Dear Friends... Welcome to the 2009 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival! Now in our sixth year, we are again pleased to present Missoula with the best in documentary film from around the world. The 2009 installment includes 143 extraordinary films from more than 30 countries, a selection chosen from nearly 1000 submissions. The program is truly distinguished, offering the most diverse exhibition of work to ever screen under the Big Sky. This year’s films cover the gamut of possibilities within the non-fiction form, with topics ranging from the ivory-billed woodpecker to art cars; from rock docs to opera; from Antarctica to Swaziland! Special Features include retrospectives of filmmakers Ron Mann & Joe Berlinger (both in attendance) and live musical accompaniment to silent film by the world renowned Alloy Orchestra. Downtown Missoula’s historic Wilma Theatre, the 1100-seat venue that houses Montana’s largest screen, once again hosts a visual immersion into a world where reality plays itself. With packed audiences of avid moviegoers, most films are accompanied by a Q&A with their respective filmmakers. We cordially invite you to the Wilma Theatre, February 13 - 22, 2009, as we showcase the best in compelling and artistic nonfiction film. Enjoy! Mike Steinberg Festival Director Table of Contents PAGE Welcome from the Big Sky Film Institute 3 Ticket Information and Pass Prices 5 Festival Jury 6 Special Events 8 Special Features 10 Schedule of Films 12 Film Descriptions (Alphabetical) 16 Festival Contact Big Sky Documentary Film Festival Wilma Theatre, 131 Higgins Avenue, Ste. 3-6 Missoula, MT 59802 (406) 541-3456 (FILM) www.bigskyfilmfest.org [email protected] Cover Art: Greg Twigg Production: Dan Funsch 1 The Big Sky Film Institute Festival Staff Celebrating and Supporting the Documentary Arts in the American West Documentaries connect us with the human experience like no other art form. -

Gogol Bordello Bio

GOGOL BORDELLO BIO “I’ve come full circle and I’m comfortable being a total outsider,” says Gogol Bordello’s Eugene Hutz, explaining the philosophy behind the band’s new album, Pura Vida Conspiracy. Like everything they’ve ever done, this outing is an uncategorizable blend of international influences, anchored by the gypsy rhythms Hutz grew up with in Ukraine. “Most people are looking for a box to put stuff in,” he says. “I try to avoid it. The message of this record is the quest for self-knowledge beyond borders and nationalities. Every culture is a useful mask, but it is just a mask. To get to know your actual human self, you have to get behind all the masks. With all the time I’ve spent in Latin America, living and loving, I realized I’ll never be Argentinean or Brazilian, just like I’ll never be Ukrainian. If you have true human spirit, you can’t fit into any genre, nationality or culture. To be a true citizen of the world, you can only be an ultimate outsider.” Hutz chose Pura Vida Conspiracy as the title because it represents everything the band has been moving toward since they first formed over a decade ago. “We’re not a whimsical band with a whimsical message and some languages offer things that others don't. As I made my way through Spanish, the phrase ‘pura vida’ - pure life - struck me. In Spanish, ‘pura vida’ has the gusto that true life should have, as opposed to words in English, French or Russian. -

ON-SALE THURSDAY 10.25 at 11:11Am Gogol

ON-SALE THURSDAY 10.25 at 11:11am Gogol Bordello, Shpongle’s Quixotic Masquerade, The Glitch Mob (DJ Set), Trentemoller (DJ Set), Diego’s Umbrella, Realistic Orchestra, Vau de Vire Society, Christian Martin, Worthy, Quixotic, Pumpkin, and Plaza de Funk headline LUNASEA themed NYE lineup. anonEvents, and SunsetSF bring you the 13th edition of the Bay Area’s beloved New Year's Eve celebration of all things artistic What: Sea of Dreams New Year's Eve When: Saturday, December 31, 2012 from 8pm-4am Where: The Concourse Center, 635 8th Street, San Francisco General info: www.seaofdreamsnye.com Organizers: anonEvents, SunsetSF Press contact: Kelly Edwards, [email protected] Sponsorship info: [email protected] Admissions: 18+ Admitted Tickets: On-sale online at seaofdreamsnye.com instore Tickets Info available soon… Vip experience: Ring in 2013 in style and luxury at Sea of Dreams by upgrading to a VIP ticket. The VIP areas will offer prime viewing, special décor, a free coat check area, exclusive restrooms (main stage area) and tables for seating. Free tapas and two complimentary drinktickets will be available in the VIP areas. VIP areas will also boast premier viewing of both East Stage (Gogol Bordello, Shpongle, Diego’s Umbrella) and the West Stage (The Glitch Mob, Trentemoller, Realistic Orchestra, Pumpkin). Each VIP admission also receives a free commemorative Sea of Dreams poster. MUSIC LINEUP: more details at www.seaofdreamsnye.com Gogol Bordello www.gogolbordello.com Shpongle’s Quixotic Masquerade www.shpongle.com The