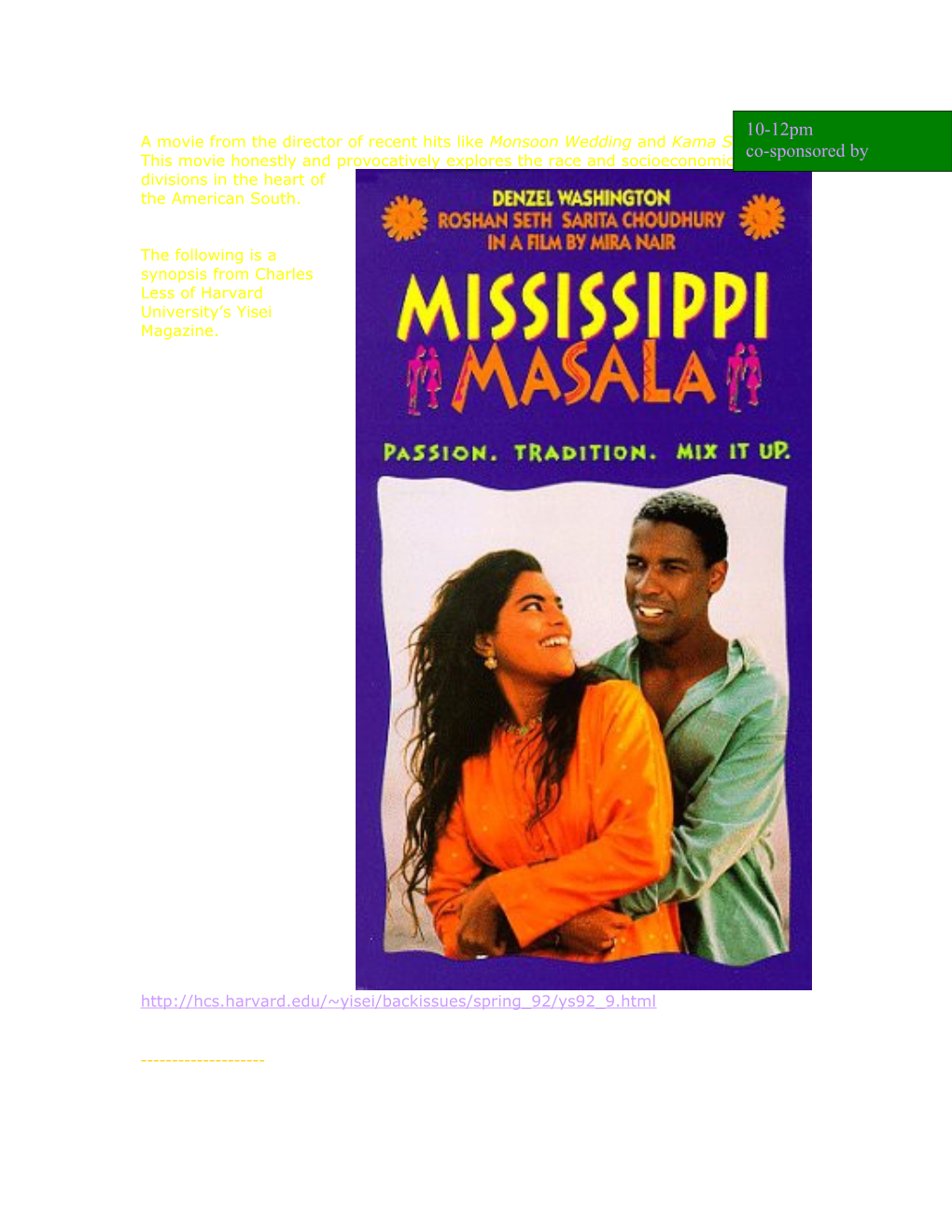

10-12pm A movie from the director of recent hits like Monsoon Wedding and Kama Sutraco-sponsored. by This movie honestly and provocatively explores the race and socioeconomic divisions in the heart of the American South.

The following is a synopsis from Charles Less of Harvard University’s Yisei Magazine.

http://hcs.harvard.edu/~yisei/backissues/spring_92/ys92_9.html

------This year, Asians can look to Mississippi Masala, the latest project of Indian director Mira Nair (whose directorial debut Saloom Bombay was an Academy Award nominee in 1989 for Best Foreign Film). In this interracial romance between an Asian Indian woman and a black man in a small Southern town, the viewers are brought into the uncharted territory of an Asian American community and are faced with a rare, detailed look at the racial diversity this country offers.

The setting of Masala is Greenwood, Mississippi. There, Asian Indians are a prominent minority in a community mostly populated by blacks and whites. Mina (Sarita Choudhury) is a young Indian woman in her twenties, working for her father Jay (Roshan Seth) who helps manage his nephew Anil’s hotel, while her mother Kinnu (Sharmila Tagore) runs a neighborhood liquor store. While borrowing Anil’s car, Mina accidentally rear-ends a van belonging to Demetrius (Denzel Washington), a young black man who operates a carpet cleaning service. This crash serves as their initial introduction; a later encounter in a night club marks the beginning of their relationship, which blossoms until Mina’s busybody relatives discover them together in bed.

Intertwined with the development of the love story is an examination of the Indian community. Under Nair’s direction, Asians are actually real people, free of the elusive, mysterious quality so prevalent in the stereotype. At Anil’s wedding ceremony, for instance, against the background of traditional rites and sitar music, beyond the bindi marks and women’s saris, are the other realities of the community: friends gossiping, little kids playing cops and robbers, faces whose expressions range from anticipation to utter boredom. The details are small, but they add dimension to a community whose principle exposure in American cinema has been as intensely religious (the cult in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom) and/or excessively fatalistic (the professor in A Passage to India.) Even more depth is to be found in Mina, a young woman who loves her family and respects her culture but needs her parents to understand that in America, she faces a different set of situations than they did, the most obvious being her non-Indian lover. A clash of cultural values familiar to Asian Americans, her story has a welcome presence on the big screen. Although Mina lapses into a trite love-can-conquer-all mentality that makes her situation look like another episode of youthful rebellion near the end of Mississippi Masala, the depth of her character, so rare for an Asian role, is nonetheless important.