The Missing Girls: Responding to Female Feticide and Infanticide In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Exploratory Study Into Honor Violence Measurement Methods

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Report on Exploratory Study into Honor Violence Measurement Methods Author(s): Cynthia Helba, Ph.D., Matthew Bernstein, Mariel Leonard, Erin Bauer Document No.: 248879 Date Received: May 2015 Award Number: N/A This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Report on Exploratory Study into Honor Violence Measurement Methods Authors Cynthia Helba, Ph.D. Matthew Bernstein Mariel Leonard Erin Bauer November 26, 2014 U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics Prepared by: 810 Seventh Street, NW Westat Washington, DC 20531 An Employee-Owned Research Corporation® 1600 Research Boulevard Rockville, Maryland 20850-3129 (301) 251-1500 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Table of Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction and Overview ............................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Summary of Findings ........................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Defining Honor Violence .................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Demographics of Honor Violence Victims ...................................... 1-5 1.4 Future of Honor Violence ................................................................... 1-6 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................... -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

Female Infanticide in 19Th-Century India: a Genocide?

Advances in Historical Studies, 2014, 3, 269-284 Published Online December 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2014.35022 Female Infanticide in 19th-Century India: A Genocide? Pramod Kumar Srivastava Department of Western History, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Email: [email protected] Received 15 September 2014; revised 19 October 2014; accepted 31 October 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In post-colonial India the female foeticide, a practice evolved from customary female infanticide of pre-colonial and colonial period, committed though in separate incidents, has made it almost a unified wave of mass murder. It does not fulfil the widely accepted existing definition of genocide but the high rate of abortion of legitimate girl-foetus by Indian parents makes their crime a kind of group killing or genocide. The female foeticide in post-colonial India is not a modern phenomenon but was also prevalent in pre-colonial India since antiquity as female infanticide and the custom continued in the 19th century in many communities of colonial India, documentation of which are widely available in various archives. In spite of the Act of 1870 passed by the Colonial Government to suppress the practice, treating it a murder and punishing the perpetrators of the crime with sentence of death or transportation for life, the crime of murdering their girl children did not stop. During a period of five to ten years after the promulgation of the Act around 333 cases of female infanticide were tried and 16 mothers were sentenced to death, 133 to transportation for life and others for various terms of rigorous imprisonment in colonial India excluding British Burma and Assam where no such crime was reported. -

Interpreting Sati: the Omplexc Relationship Between Gender and Power in India Cheyanne Cierpial Denison University

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 14 Article 2 2015 Interpreting Sati: The omplexC Relationship Between Gender and Power In India Cheyanne Cierpial Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Cierpial, Cheyanne (2015) "Interpreting Sati: The ompC lex Relationship Between Gender and Power In India," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 14 , Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol14/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Cierpial: Interpreting Sati: The Complex Relationship Between Gender and P INTERPRETING SATI: THE COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN GENDER AND POWER IN INDIA Interpreting Sati: The Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power In India Cheyanne Cierpial A recurring theme encountered in Hinduism is the significance of context sensitivity. In order to understand the religion, one must thoroughly examine and interpret the context surrounding a topic in Hinduism.1 Context sensitivity is nec- essary in understanding the role of gender and power in Indian society, as an exploration of patriarchal values, religious freedoms, and the daily ideologies as- sociated with both intertwine to create a complicated and elaborate relationship. The act of sati, or widow burning, is a place of intersection between these values and therefore requires in-depth scholarly consideration to come to a more fully adequate understanding. The controversy surrounding sati among religion schol- ars and feminist theorists reflects the difficulties in understanding the elaborate relationship between power and gender as well as the importance of context sen- sitivity in the study of women and gender in Hinduism. -

Forms of Femicide

29 Forms of Femicide Facilitate. Educate. Collaborate. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the AUTHOR views of the Government of Ontario or the Nicole Etherington, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women Against Women & Children. While all and Children, Faculty of Education, Western University. reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this publication, no liability is assumed for any errors or omissions. SUGGESTED CITATION Etherington, N., Baker, L. (June 2015). Forms of Femicide. Learning Network Brief (29). London, Ontario: Learning The Learning Network is an initiative of the Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children. against Women & Children, based at the http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Faculty of Education, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. Download copies at: http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/ Copyright: 2015 Learning Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children. www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Funded by: Page 2 of 5 Forms of Femicide Learning Network Brief 29 Forms of Femicide Femicide is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the intentional killing of women because they are women; however, a broader definition includes any killings of women and girls.’i Femicide is the most extreme form of violence against women on the continuum of violence and discrimination against women and girls. There are numerous manifestations of femicide recognized by the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Office. ii It is important to note that the following categories of femicide are not always discrete and may overlap in some instances of femicide. -

The Political Economy of Marriage: Joanne Payton

‘Honour’ and the political economy of marriage Joanne Payton Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD, 2015 i DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 Summary ‘Honour’-based violence (HBV) is defined as a form of crime, predominantly against women, committed by the agnates of the victim, often in collaboration, which are justified by the victims’ perceived violation of social norms, particularly those around sexuality and gender roles. While HBV is often considered as a cultural phenomenon, I argue that the cross-cultural distribution of crimes fitting this definition prohibits a purely cultural explanation. I advance an alternate explanation for HBV through a deployment of the cultural materialist strategy and the anthropological theories of Pierre Bourdieu, Claude Lévi-Strauss (as interpreted by Gayle Rubin) and Eric Wolf. -

Intrafamily Femicide in Defence of Honour: the Case of Jordan

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol22, No 1, pp 65 – 82, 2001 Intrafamilyf emicidein de fenceo f honour:the case o fJordan FADIA FAQIR ABSTRACT This article deals with the issue of honourkillings, aparticular type of intrafamily femicide in defenceof honourin Jordan.The legal, social, religious, nationalist andtribal dimensionsand arguments on such killings are presented.Drawing on Arabic and English source material the role ofrumour, social values andother dynamicsin normalisingthis practice in Jordantoday is analysed.Honour killings, whichcontradict manyinternational andnational laws andcovenants, are clearly connectedto the subordinationof womenin Jordanand to the ‘criming down’of domestic violence.The prevailing discrim- inatory culture cannotchange without implementing a comprehensivepro- grammefor socio-legal andpolitical reform. The debateon harm Scholarlyconcentration on harm to womenhas beencriticised recently bymany feminists, whoargue that the debatefocuses solely onviolence, victimisation andoppression of women. 1 TheArab world, however, has notreached the stage wherea similar debateis possible becausedocumentation of and discussion aboutviolence against womenare still in the infancystage. Suchdebates within the Anglo-Saxoncontext, theref ore,do not seem relevant in their entirety to Arabwomen’ s experiences,since most suchwomen are still occupantsof the domestic, private space.Other Western theories, models andanalysis, however, canbe transferred andapplied (with caution)to the Arabexperience of gender violence,which is still largely undocumented. Whatis violence againstwomen? Violenceis the use ofphysical forceto inict injuryon others,but this denition couldbe widened to includeimproper treatment orverbal abuse. It takes place atmacrolevels, amongnation states andwithin communities, andat micro levels within intimate relationships. Theuse ofviolence to maintain privilege turned graduallyinto ‘the systematic andglobal destruction ofwomen’ , 2 orfemicide, 3 with the institutionalisation ofpatriarchy over the centuries. -

Psychiatric Considerations on Infanticide: Throwing the Baby Out

Psychiatria Danubina, 2020; Vol. 32, Suppl. 1, pp 24-28 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia PSYCHIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS ON INFANTICIDE: THROWING THE BABY OUT WITH THE BATHWATER Anne-Frederique Naviaux1, Pascal Janne2 & Maximilien Gourdin2 1College of Psychiatrists of Ireland and Health Service Executive (HSE) Summerhill Community Mental Health Service, Summerhill, Wexford, Ireland 2Université Catholique de Louvain, CHU UCL Namur, Yvoir, Belgium SUMMARY Background: Infanticide is not a new concept. It is often confused with child murder, neonaticide, filicide or even genderside. Each of these concepts has to be defined clearly in order to be understood. Through time reasons for infanticide have evolved depending on multiple factors such as culture, religion, beliefs system, or attempts to control the population. It was once seen as a moral virtue. So what has changed? Subjects and methods: Between January 2020 and May 2020, a literature search based on electronic bibliographic databases as well as other sources of information (grey literature) was conducted in order to investigate the most recent data on infanticide and child murder, especially the newest socio-economic and psychiatric considerations as well as the different reasons why a mother or a father ends up killing their own child and the Irish situation. Results: Recent works on the subject demonstrate how some new socio economic factors and family considerations impact on infanticide. Mental illness, especially depression and psychosis, is often part of the picture and represent a very high risk factor to commit infanticide and filicide. Fathers and mothers do not proceed the same way nor for the same reasons when they kill their offspring. -

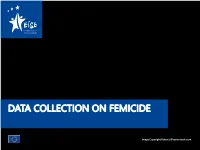

Data Collection on Femicide

DATA COLLECTION ON FEMICIDE Image Copyright:fizkes's/Shutterstock.com CHALLENGES FOR DATA COLLECTION • No international defintion of “femicide” • Terminology of femicide not adapted to statistical purposes • Lack of disaggregated approaches to data collection • Technical obstacles in data collection at national level LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT Victims’ Istanbul Rights Convention Directive Report of CEDAW GR UNODC 35 (49) (2019) & Road Map DEFINITIONS BY ACADEMIA The killing of females by males because they are females (Russell, D. 1976) The murder of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure or a sense of ownership over women (Caputi and Russell 1990) The misogynistic killings of women by men (Radford & Russell, 1992) DEFINITIONS OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS Vienna WHO MESECVI ICCS Declaration (UN) Femicide is the The The violent killing of women An unlawful death killing of women and intentional because because of gender, inflicted upon a girls because of their murder of whether it occurs within the person with the gender women family, domestic unit or any intent to cause because they other interpersonal death or serious are women relationship, within the injury community, by any individual or when committed or tolerated by the state or its agents, either by act or omission COMPONENTS Intentional Killing 24 Death related to unsafe abortion 14 FGM-related death 9 Killing of a partner or espouse 7 Gender-based act and/or killing of a woman 6 Death of women resultinf of IPV 5 COMPONENTS OF FEMICIDE OF COMPONENTS Dowry-related deaths Females foeticide Honour-based Killings 0 10 20 30 NUMBER OF MEMBER STATES COMPONENTS KEY COMPONENTS Gender Gender inequalities motivation EIGE’s DEFINITION AND INDICATOR The killing of a woman by an intimate partner and the death of a woman as a result of a practice that is harmful to women. -

Gender and the Politics of Female Infanticide and Prostitution Regulation Margaret Kuo, California State University, Long Beach

REVIEW ESSAY Gender and the Politics of Female Infanticide and Prostitution Regulation Margaret Kuo, California State University, Long Beach Michelle T. King. Between Birth and Death: Female Infanticide in Nineteenth-Century China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014. 264 pp. $50.00 (cloth/e-book). Elizabeth J. Remick. Regulating Prostitution in China: Gender and Local Statebuilding, 1900– 1937. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014. 288 pp. $45.00 (cloth/e-book). The two works under review are both compelling historical studies that use gender as a category of analysis to make important contributions to our understanding of the construction of the modern Chinese state, the periodization of modern Chinese history, and the political and cultural significance of controlling the female body. While both books engage with gender as broadly construed, they adopt different approaches. Michelle King’s analysis focuses on discursive representations that took place, for the most part, outside the context of the state— what Confucian elites, foreign experts and missionaries, and Chinese nationalists wrote about female infanticide over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This discursive approach has been used before but rarely to such insightful effect. King’s research deepens our understanding of gender and imperialism in the nineteenth century by illustrating how imperialist notions of China as a backward and heathen place were constructed in part on dubious claims that identified female infanticide as an emblematically Chinese cultural practice. Elizabeth Remick’s gender analysis, in contrast, centers on the state institutions that were developed in the early 1900s to regulate prostitution, including tax policies, licensing fees, zoning regulations, medical examinations, and police supervision. -

Review Article Female Infanticide in India and Its Relevance to Nepal

Review Article Female infanticide in India and its relevance to Nepal Michelle Vickery1, Edwin van Teijlingen2 1Sociology and Anthropology Graduate [email protected] Faculty of Health & Social Sciences Bournemouth University Bournemouth, UK 2 Professor of Reproductive Health Research [email protected] Faculty of Health & Social Sciences Bournemouth University Bournemouth, UK Abstract This paper offers a sociological analysis of female infanticide in India with the aim of provoking readers to consider similar issues in Nepal. India and Nepal have a close relationship; their citizens are able to travel freely between the two countries and they share many similarities in their cultural, religious and social traditions. This has meant that people and ideas are easily exchanged between the two, making it necessary to consider the Indian phenomenon of female infanticide in Nepalese context. Introduction Gender selection and its subsequent female infanticide (FI) remains a problem for many countries today, most notably India (Mittal et al. 2013; Srivastava 2014). It is calculated that India has the largest number of missing women (Grech and Mamo 2014) due to the patriarchal customs which perpetuate male preference (Sen 2003; Srinivasan and Bedi 2006; Diamond-Smith et al. 2008; Chidamabaranathan et al. 2011; Perwez 2013) and promote the selective elimination of females through practices such as infanticide and sex- selective abortion (Patel 2013). Although sex-selective abortion may be considered a related phenomenon to FI (Scrimshaw 1983), this paper will focus on exploring reasons for the latter and linking it to the Nepalese context. Towards the end of the 20th century, Sen and Dreze (1989) estimated that 37 million women were missing in India because of such pervasive ISSN: 2091-1041 I VOLUME 3 I2017 JMMIHS-79 Review Article anti-female practices. -

Discrimination Against the Girl Child FEMALE INFANTICIDE, FEMALE GENITAL CUTTING and HONOR KILLING

Discrimination against the girl child FEMALE INFANTICIDE, FEMALE GENITAL CUTTING AND HONOR KILLING BOOKLET NO. 6 IN A SERIES ON INTERNATIONAL YOUTH ISSUES YOUTH ADVOCATE PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL discrimination against the girl child Female Infanticide, Female Genital Cutting and Honor Killing BY KATHERINE S. NEWELL ELIN ROSS CARRIE MCVICKER AND JEN CROMWELL ABOUT YOUTH ADVOCATE PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL The mission of Youth Advocate Program International is to promote the rights and well-being of the world’s youth, giving particular attention to the plight of troubled and needy youth and to those victimized by conflict, exploitation, and state and personal violence. The Youth Advocate Program International was incorporated in 1994 and is an affiliate organization of the National Youth Advocate Program, Inc. (NYAP). NYAP is a private, nonprofit youth advocacy organization that develops and implements community-based services for troubled and needy youth. It is the parent organization of eight state affiliate programs that offer services in their respective states: Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana, South Carolina, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas and Arizona. Youth Advocate Program International is registered in the United States as a 501(c)(3) organization. © 2000 by the Youth Advocate Program International. All rights reserved. Reprinting by permission. ISBN 0-9663709-7-X Editor: Laura Barnitz Contributors: Barbara Burton, Phd., Aleli Domingo, Barbara Ginsburg, Nancy Nye, Pomme Ratanakanaka, and Claudia Sauerborn Graphic Design: Fine Points Multimedia Services Photos: Front: Asha Mohamud and Margot Sluka. About the photo: 7-year-old girl from Allenfuto, Lower Shabelle Region of Somalia. Back: About the photo: Queen Rania Al Abdullah of Jordan. First Edition Printed by Master Print, Inc.