The Cash Cage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

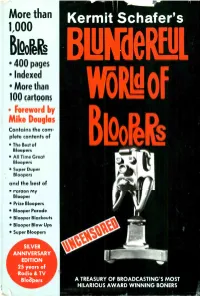

Blunderful-World-Of-Bloopers.Pdf

o More than Kermit Schafer's 1,000 BEQ01416. BLlfdel 400 pages Indexed More than 100 cartoons WÖLof Foreword by Mike Douglas Contains the com- plete contents of The Best of Boo Ittli Bloopers All Time Great Bloopers Super Duper Bloopers and the best of Pardon My Blooper Prize Bloopers Blooper Parade Blooper Blackouts Blooper Blow Ups Super Bloopers SILVER ANNIVERSARY EDITION 25 years of Radio & TV Bloópers A TREASURY OF BROADCASTING'S MOST HILARIOUS AWARD WINNING BONERS Kermit Schafer, the international authority on lip -slip- pers, is a veteran New York radio, TV, film and recording Producer Kermit producer. Several Schafer presents his Blooper record al- Bloopy Award, the sym- bums and books bol of human error in have been best- broadcasting. sellers. His other Blooper projects include "Blooperama," a night club and lecture show featuring audio and video tape and film; TV specials; a full - length "Pardon My Blooper" movie and "The Blooper Game" a TV quiz program. His forthcoming autobiography is entitled "I Never Make Misteaks." Another Schafer project is the establish- ment of a Blooper Hall of Fame. In between his many trips to England, where he has in- troduced his Blooper works, he lectures on college campuses. Also formed is the Blooper Snooper Club, where members who submit Bloopers be- come eligible for prizes. Fans who wish club information or would like to submit material can write to: Kermit Schafer Blooper Enterprises Inc. Box 43 -1925 South Miami, Florida 33143 (Left) Producer Kermit on My Blooper" movie opening. (Right) The million -seller gold Blooper record. -

1001 Classic Commercials 3 DVDS

1001 classic commercials 3 DVDS. 16 horas de publicidad americana de los años 50, 60 y 70, clasificada por sectores. En total, 1001 spots. A continuación, una relación de los spots que puedes disfrutar: FOOD (191) BEVERAGES (47) 1. Coca-Cola: Arnold Palmer, Willie Mays, etc. (1960s) 2. Coca-Cola: Mary Ann Lynch - Stewardess (1960s) 3. Coca-Cola: 7 cents off – Animated (1960s) 4. Coca-Cola: 7 cents off – Animated (1960s) 5. Coca-Cola: “Everybody Need a Little Sunshine” (1960s) 6. Coca-Cola: Fortunes Jingle (1960s) 7. Coca-Cola: Take 5 – Animated (1960s) 8. Pet Milk: Mother and Child (1960s) 9. 7UP: Wet and Wild (1960s) 10. 7UP: Fresh Up Freddie – Animated (1960s) 11. 7UP: Peter Max-ish (1960s) 12. 7UP: Roller Coaster (1960s) 13. Kool Aid: Bugs Bunny and the Monkees (1967) 14. Kool Aid: Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd Winter Sports (1965) 15. Kool Aid: Mom and kids in backyard singing (1950s) 16. Shasta Orange: Frankenstein parody Narrated by Tom Bosley and starring John Feidler (1960s) 17. Shasta Cola: R. Crumb-ish animation – Narrated by Tom Bosley (1960s) 18. Shasta Cherry Cola: Car Crash (1960s) 19. Nestle’s Quick: Jimmy Nelson, Farfel & Danny O’Day (1950s) 20. Tang: Bugs Bunny & Daffy Duck Shooting Gallery (1960s) 21. Gallo Wine: Grenache Rose (1960s) 22. Tea Council: Ed Roberts (1950s) 23. Evaporated Milk: Ed & Helen Prentiss (1950s) 24. Prune Juice: Olan Soule (1960s) 25. Carnation Instant Breakfast: Outer Space (1960s) 26. Carnation Instant Breakfast: “Really Good Days!” (1960s) 27. Carnation: “Annie Oakley” 28. Carnation: Animated on the Farm (1960s) 29. Carnation: Fresh From the Dairy (1960s) 30. -

Teip Dennis Hart

Lad Greinit Radio Sho ••••••••••• teip Th inside of ne work great tprop_ 41111 Dennis Hart Monitor The Last Great Radio Show Dennis Hart Writers Club Press San Jose New York Lincoln Shanghai Monitor The Last Great Radio Show All Rights Reserved 0 2002 by Dennis Hart No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the publisher. Writers Club Press an imprint of iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 5220 S. 16th St., Suite 200 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com ISBN: 0-595-21395-2 Printed in the United States of America Monitor . .. TO the men and women who made Monitor Foreword This book took about 40 years to write—and if that seems atad too long, let me hasten to explain. Iwas about 12 years old when, one Saturday in the living room in my California home, Iwas twisting the dial on my parents' big Grunow All- Wave Radio, looking for my favorite rock-radio station. What Iheard was, well, life-changing. Some strange, off-the-wall sound coming from that giant radio compelled me to stay tuned to aprogram I'd never encountered before—a show that sounded Very Big Time. For one thing, aguy Iknew as "Mr. Magoo" was hosting it—Jim Backus. What in the world was be doing on the radio? He was hosting Monitor, of course. And the sound that beckoned me was, of course, The Beacon—the Monitor Beacon. -

Barnes Hospital Bulletin

Barnes Hospital, St. Louis, Mo. April, 1984, Vol. XXXVIII, No. 4 Auxiliary celebrates 25th anniversary Twenty-five years of dedicated service and finan- cial support will be celebrated by the Barnes Hos- pital Auxiliary at its annual spring luncheon and business meeting April 26. Elaine Viets, a feature columnist with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, will be the guest speaker. The Auxiliary's annual meeting begins at 11 a.m., with a cash bar and the silver anniversary lun- cheon following. The event is being held at the Radisson Hotel, Ninth Street and Convention Plaza. One of the afternoon's highlights will be the pre- sentation of a check by Auxiliary president Mary M Ann Fritschle to Barnes board of directors chair- man Harold E. Thayer representing the Auxiliary's final installment of a $1 million pledge, made in 1981, to help finance the construction of new trau- ma center facilities at Barnes. The Auxiliary has already donated $685,000 to the project, which should be completed in early 1985. Before: A blockage in a coronary artery cuts off the sup- After: A new drug, t-PA, moves directlym to the clot and Since its inception in 1959, the Auxiliary, frequent- ply of oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle. A heart dissolves the blockage, re-establishing blood flow to ly named as the top such organization in the state, attack results. the heart muscle. has given $3,260,723.72 to Barnes. The Auxiliary makes its yearly donations to the hospital through its sponsorship of the Wishing Well Gift and Flower Drug researched here least two ways: (1) by harvesting a human tissue Shops, Nearly New Shop, Tribute Fund and Baby culture system through a lengthy and expensive Photo Service. -

Delaura Middle School Student Newspaper May 22Nd, 2020 Volume III - Issue VIII Flag Design: Lillian Black and Declan Daleiden

DeLaura Middle School Student Newspaper May 22nd, 2020 Volume III - Issue VIII Flag Design: Lillian Black and Declan Daleiden Farewell Letter From Your Editor Thoughts from 8th Graders -“I am going to Satellite and my favorite Kynsley Penny Scottie Sunrise Staff memory from DeLaura was playing our first note in band.”- Taylor G. This school year has been crazy, Our Scottie 8th graders are moving on to wonderful, and full of memories. Some of high school. We reached out to a few of -“I’ll be going to Satellite, and my favorite my favorite memories are going to them and asked some of the following memory was when me and my friends in perform at Disney, being elected as questions: What high school will you be seventh grade social studies started a attending? What was a favorite memory editor-in-chief for the school newspaper, really dumb debate. I hope in high school from DeLaura? What are you most spending time with my friends, and looking forward to about high school? I get a girlfriend and have good grades. making new friends that I am going to What will you miss most about DeLaura? Imma miss Tallyha and my sevie friends.” miss. Being a part of the newspaper for - Caitlyn R. Check out what they had to say: the past two years has been amazing, and I would not change it. Newspaper club -“My favorite memory this year was the -“I am attending Satellite and my favorite has allowed me to write about what I love chorus field trips.”- Taegan J. -

Front Jan 28

Sparta Home Show at the shooting complex this weekend Jackson unveiling Page 7 Chester sports talk Serving The Area With Local News Since 1980 Page 10 Perry writes off loans Page 20 © Copyright 2015, County Journal www.countyjournalnews.com Volume 37 Number 4 28 Pages Your Local News Leader Thursday, January 28, 2016 75¢ SCTP moves ’16 national championship to Ohio By Travis Lott ing officials had stopped re- Southwestern Illinois has turning his emails. lost a major battle. “I kind of assumed that was Shoot has The Grand American and the direction in which they AIM may return to the World were going,” Heffley said. “I a local Shooting and Recreational just wasn’t going to make the Complex this year, but the announcement for them.” economic Scholastic Clay Target Pro- State Senator Dave Luechte- gram’s national champion- feld said he is disappointed impact of about ships will not. that this has happened. Those who have been follow- “We offered them assurance $8 million ing the County Journal’s cov- that the complex would be erage of the fight over the open to them, but undoubt- complex know that the com- edly, that assurance came a show the governor who’s plex previously averaged a little late,” Luechtefeld said. boss,” Luechtefeld said. $22 million impact on the Luechtefeld said he believes Sparta Mayor Jason Schlim- area. the impasse is essentially at me said the loss of the SCTP The SCTP championships the same standstill, and in is a loss for the area. accounted for roughly $8 mil- order to get the complex re- “It’s your gas stations. -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 29, No. 01

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus ?^^ .«*^=^ '•^=^%^,-..^»*. -^ ^^^ Vol. 29, No. I, January-February, 1951 W^m»^ -r ^M;H !U »^... -••.•.;_i! •<..3;^- .l-»~' Zhc Notre Dame Alumnus Class Reunions June S, 9, 10 VoL 29 No. 1 January-February, 1951 CLASSES RETURNING James E. Armstrong. '25. Editor John P. Bums. '34.'Manoging Editor 1901,'06,'11, '16 John N. Cacldey, Jr.. '37. Associate Editor '21 This magazine is published bi-monthly by the University of Notre '26 Dame, Notre Dame, Ind. Entered as second Aass matter OcL 1, 1939, at the Postoifice, Notre Dame, Ind., under the act of Aug. 24, '31 1912. '36 '41, '46 Table of Contents FRIDAY, JUNE 8 ALUMNI BOARD MEETING 3 (all times Central Daylight Saving) BACCALAUREATE SERMON 4 General Registration Law Building Lobby FOOTBALLL TICKETS 6 Class Registration in class halls FOUNDATION REPORT , 8 Golf Tournament, Class Reunion Dinners, Smokers "THE KEY TO PEACE" 9 COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS 10 SATURDAY, JUNE 9 BOOKS 11 Class Masses, Pictures, Elections CLUBS ..._ 13 More Golf CLASSES 22 President's noon luncheon for 25-year class Baseball Game, Cartier Field, 1:30 p.m. Academic review by deans, 2:00-3:30 p.m., Wash BOARD OF DIRECTORS ington Hall OFFICERS Moot Court Finals, 2:30 p.m. and Law Cocktail LEO B. WARD, '20 Jlonorary President party. Law Building, 4-6 p.m. R. Co.VROv ScoGcr.vs, '24 President Annual Alumni Banquet, 6 p.m., dining hall—The WiLU,\M J. -

Naples on Jeopardy!

The Monitor • Naples, Texas 75568-0039 • Thursday, September 28, 2017 • Page 9 Annual meeting and luncheon at Springhill Cemetery Oct. 7 Television Show Features Naples Members and friends of the Springhill Cemetery Associa- tion will meet for the association's annual business meeting and covered dish luncheon at 10 a.m., on Saturday, October 7, at the restored historical church at Rocky Branch. Naples gains a dab of TV fame The luncheon will be served immediately after the busi- ness meeting and water, ice and cups will be provided. with Alex Trebek and "Jeopardy!" "We would like to extend our sincere invitation and your "Jeopardy!" is apparently one of the favorite TV shows for input at the meeting," said Jimmy Gilliam, association folks in the Naples area and it really stirred up the local president. "If you have any questions or comments regarding viewers on a recent Tuesday when NAPLES was included in the condition of the cemetery, please contact me at 903-897- one of the "Answer and Question" rounds for contestants. 5169." It was so well viewed, a former Naples resident, Alexier D. Current officers include Jimmy Gilliam, president; Jan Barbour, an attorney in Dallas, took some video of the show Ragland, vice president; Rhoda Bicknell, secretary; Nita and sent it to us. She wasn't the only one who took note of the Beth Traylor, treasurer; and board members Bobby Alford, local town making history. A number of local residents called Glen Ragland, Pam Spann and Willie Giles Smith. to see if the newspaper knew about it. -

38Th Annual DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT EMMY ® AWARDS

38th Annual DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT ® EMMY AWARDS The Las Vegas Hilton Ballroom, Sunday, June 19, 2011 Congratulations to our 2010 Daytime Emmy Nominees & Winners! Transfomers Prime® Outstanding Writing in Animation Duane Capizzi, Writer/Producer Steven Melching, Writer Nicole Dubuc, Writer Joseph Kuhr, Writer Marsha Griffin, Writer Outstanding Performer in an Animated Program Peter Cullen as Optimus Prime Outstanding Directing in an Animated Program David Hartman, Supervising Director/Director Shaunt Nigoghossian, Director Todd Waterman, Director Vinton Heuck, Director Susan Blu, Voice Director Outstanding Individual Achievement in Animation Vince Toyama, Background Design, WINNER! Christophe Vacher, Color Design, WINNER! Outstanding Achievement in Music Direction and Composition Brian Tyler, Composer Family Game Night™ Outstanding Game Show Host Todd Newton Pictureka™ Outstanding Achievement in Main Title and Graphic Design Terry Scott, Title Designer Matthew Melone, Title Designer Matthew Daday, Title Designer Liz Scaggs, Lead Animator © 2011 Hasbro. All Rights Reserved. TM and ® denote U.S. Trademarks. From Our Entire Hasbro Studios Family Studios Emmy Nominee ad_f.indd 1 5/31/11 12:15 PM This is your night! Welcome to the 38th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy® Awards. Tonight we are proud to honor and celebrate the best in Daytime Television by awarding the coveted Emmy Award. For the second year in a row, we are broadcasting live from the Las Vegas Hilton, where we hope to captivate and dazzle you with all the energy and excitement this city can offer. With Wayne Brady to lead the way and special guests such as Carol Burnett, Anderson Cooper and Penn & Teller, I’m sure we’re in for an evening of fun and surprises. -

Now 160 Years Later, Harney Is Under Fire

Monday, 3.30.15 ON THE WEB: www.yankton.net views VIEWS PAGE: [email protected] PAGE 4 PRESS&DAKOTAN The Press Dakotan THE DAKOTAS’ OLDEST NEWSPAPER | FOUndED 1861 Yankton Media, Inc., 319 Walnut St., Yankton, SD 57078 CONTACT US OPINION OTHER VIEWS PHONE: (605) 665-7811 (800) 743-2968 NEWS FAX: A Welcome Idea (605) 665-1721 ADVERTISING FAX: (605) 665-0288 For Congress WEBSITE: www.yankton.net OMAHA WORLD-HERALD (March 20): Chuck Hagel, a Republican, ––––– did it. So did Ben Nelson, a Democrat. As did Democrats Bob Kerrey SUBSCRIPTIONS/ and Jim Exon. CIRCULATION During their service in the U.S. Senate, those Nebraska lawmakers Extension 104 often gave their party chieftains the same message: Don’t count on [email protected] me to always vote the party line. Issues are too complicated for that. CLASSIFIED ADS I’m voting my own mind. Extension 108 In the U.S. House, Rep. Brad Ashford has begun his congressional [email protected] career on the same path. The 2nd District’s new congressman took an NEWS DEPT. independent stance in the first weeks of the new Congress by voting Extension 114 with the Republican majority to pass six of seven bills opposed by Capitol Notebook [email protected] most of Ashford’s fellow House SPORTS DEPT. Democrats. During their service in Ashford’s office says his is Extension 106 the U.S. Senate, those one of the most independent [email protected] records in the House so far — Now 160 Years Later, ADVERTISING DEPT. Nebraska lawmakers voting with the Democrats 73 Extension 122 often gave their party percent of the time (when the [email protected] chieftains the same party-line average is 93 percent) BUSINESS OFFICE — and that 30 of his 39 bills Harney Is Under Fire Extension 119 message: Don’t count include Republican co-sponsors. -

9,000 Attended Fiesta 250 Attend Two Thousand Boca Raton Turned Over $49,566 to the Lea- Mrs

1673 BOCA RATON NEWS Vol. 12, No. 65 April 20, 1967 Thursday 104 School, City Officials Okay Juvenile Jury Teen Court Due Soon Traffic law enforcement for teenagers took a giant step forward this week as officers of school and city organizations put the stamp of approval on a juvenile jury system. Student Council and Teen Town members met with the Juvenile Advisory Council Mon- day night and were asked their opinion of a jury of teens. Both groups unanimously favored in- stituting such a system as soon as traffic offender'scan be pro- secuted in city court. Rep.Donald Reed said a sta- tute change to allow teen traf- fic offenders to be haled into city court would be introduced to the Legislature in Tallahas- see next week. The bill could legally be introduced April 25. Interest was high this week in the Florida Atlantic University Semi-finalists for the Miss Boca Raton High be chosen from the six and crowned at the high No juvenile has had to appear student sidewalk art show. Here an artist and prospective client School Contest are (left) Donna Noell, Sharlene school Spring concert tonight. The concert, fea- before a city magistrate in discuss some of the paintings. Boca Raton for about two years0 Fox, Sandy Gilbert, Cindy Frambach, Janet Bold- taring the band and chorus, will be held at 8 p.m. cases continue to be backlogged izar, and Pat Roll. The girls were selected Mon- in the school auditorium. by the Police Department. day evening. Miss Boca Raton High School will According to present law, all offenders must be sent to the 10 'Make History' county level and cases referred back to the city on a individual bases. -

JEOPARDY! » As the Original Format of the Russian Intellectual Television «SVOYA IGRA»

Vol. 8 Núm. 22 /septiembre - octubre 2019 229 Artículo de investigación « JEOPARDY! » as the original format of the Russian intellectual television «SVOYA IGRA» « JEOPARDY! » КАК ОРИГИНАЛЬНЫЙ ФОРМАТ РОССИЙСКОЙ ИНТЕЛЛЕКТУАЛЬНОЙ ТЕЛЕИГРЫ «СВОЯ ИГРА» «¡JEOPARDY!» Como el formato original de la televisión intelectual rusa «SVOYA IGRA» Recibido: 12 de junio del 2019 Aceptado: 25 de julio del 2019 Written by: Grigory V. Vakku87 ORCID 0000-0001-7676-8962; SPIN-код: 3886-4740 AuthorID: 284494 Simona E. Lebedeva88 ORCID 0000-0002-0238-7531; SPIN-код: 2308-8043 AuthorID: 929149 Larisa A. Budnichenko89 ORCID 0000-0002-2609-2295; SPIN-код: 7701-3127 AuthorID: 281221 Lidia E. Malygina90 ORCID 0000-0002-0056-8160; D-6901-2019 SPIN-код: 5278 – 1225 Abstract Аннотация The article deals with the history of the origin, В статье рассматривается история formation and functioning of the American возникновения, становления и intellectual game «Jeopardy! », which is the функционирование американской original format of the Russian intellectual TV интеллектуальной игры «Jeopardy!» game «Svoya igra». The object of the research in (¡«Рискуй!»), которая является оригинальным question is an American intellectual game форматом российской интеллектуальной Jeopardy! The subject of the research is the телеигры «Своя игра». Объектом history and the specificity of this intellectual исследования выступает американская game. The work also focuses on the study of the интеллектуальная игра «Jeopardy!» features and rules of the game «Jeopardy! ». («Рискуй! »). Предмет исследования: