PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: AB870 Project Name AR NATIONAL HIGHWAY ASSET MANAGEMENT Region LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN Sector Roads and highways (80%);General public administration sector (20%) Project ID P088153 Borrower(s) ARGENTINE REPUBLIC Implementing Agency Direccion Nacional de Vialidad Av. Julio A.Roca 738 Piso 2 Argentina Tel: (5411) 4343 2857 Fax: (5411) 4331 7129 Environment Category [ ] A [X] B [ ] C [ ] FI [ ] TBD (to be determined)

Safeguard Classification [ ] S1 [X] S2 [ ] S3 [ ] SF [ ] TBD (to be determined) Date PID Prepared April 21, 2004 Date of Appraisal April 30, 2004 Authorization Date of Board Approval June 29, 2004

1. Country and Sector Background

Introduction. Argentina is emerging from the deepest political and economic crisis in generations. The social impact of the crisis has been devastating. During 2002, poverty increased dramatically. The number of poor grew by roughly 20 percentage points to more than half of the total population while the number of extreme poor nearly doubled. In rural areas, the situation is even worse, with almost three out of four people being poor today. At the core of this massive increase in poverty was the economic crisis, which led to an increase of open unemployment to 21 percent in May 2002. While about 1.3 million new jobs have been created since, about half of which are directly related to workfare programs, unemployment remains at very high levels. Formal private sector employment fell dramatically and even within the informal sector, there was a marked shift to short-term and more instable work relationships. In addition to the loss of family income through unemployment, real wages declined by an average of one-fifth in the course of 2002. The economy has now been stabilized, and the Government of Argentina (GoA) is focusing on mitigating the aftermath of the prolonged recession and crisis period through a strategy that emphasizes rebuilding the economy and delivering sustained growth within a framework of social equity. In this context, the administration is favoring economic policies that lead to economic growth over sufficiently long periods of time and with sufficiently pro-poor impacts to improve the livelihood of the population. Increased investment in infrastructure is being promoted as a means of fostering regional productivity and competitiveness, and also to restore public and private investments to levels that are commensurate with the medium term growth convergence projections (around 3%). The proposed National Highway Asset management Project supports the GoA strategy of promoting economic growth, employment, and poverty reduction.

The GoA economic development strategy, which includes as one of its pillars a comprehensive program of infrastructure investments, is supported by solid evidence showing: (i) infrastructure as an important determinant of economic growth in the country1; (ii) inequality declines with higher level of infrastructure quality and quantity2; and (iii) the importance that growth of Small and Medium Size Enterprises (SMEs) has in job creation3 and the significance of proper access to infrastructure to facilitate SME development.

1 The elasticity of GDP with respect to infrastructure stocks in Argentina has been estimated to be 0.23 (Fay and Yepes, 2003). An increase in the quality and quantity of infrastructure stock in Argentina to bring the country to the levels of Costa Rica could result in an increase of GDP growth of 1.3% per annum, while an increase in the stock of infrastructure to put Argentina at the level of Korea could cause a difference in GDP growth of 3% per annum (Severn, Calderon 2002). 2 Income inequality (as measured by a Gini coefficient or income shares) declines with higher infrastructure quality and quantity (Severn, Calderon, 2004). The main reasons are: (i) poorer individuals and underdeveloped areas get connected to the core economic activities, thus allowing them to access additional productive opportunities (Estache, 2000); and (ii) infrastructure development reduces production and transaction costs (Gannon and Liu, 1997). In Argentina, upgrading infrastructure to the level of Costa Rica or Korea could help to reduce the Gini coefficient by, respectively 0.03 and 0.06. 3 Argentine SMEs account for about 69-79 percent of employment. (World Bank Report No. 22830-AR, August 2002) . Overview. The recent devaluation of the peso introduced substantial competitive advantages to Argentine export products. Ensuring the sustainability of the growth of exports and economic recovery in general, requires a reduction in the country’s structurally high logistics costs; these costs could neutralize the competitive gains brought about by the peso devaluation. Logistic costs in Argentina represent an estimated 27 cents of every dollar exported, compared to 7 cents in the OECD4. Removing this barrier, of which the main determinant is transport costs, is of paramount importance to secure the growth of productive enterprises and, more importantly, to foster their development in marginal regions with high unemployment and poor transport connectivity.

The challenge is that, after a prolonged recession, investments in the transport sector have been limited, and basic maintenance has been cut down with priority given to those assets with higher levels of demand (those connecting areas with higher economic activity and therefore higher income). This trend has accentuated regional income disparities by discouraging productive activities in the marginal areas with entrenched pockets of poverty. Significant resources are needed to rehabilitate transport infrastructure that was neglected but is crucial to foster productivity across the country and to reduce regional disparities.

Finally, in its effort to improve competitiveness, Argentina needs to compensate for a series of structural conditions that entail high transport costs (uni-directional freight flows, fairly large distances with low traffic densities, a strong element of seasonality, and lack of intermodal integration), not only enhancing the quality of its transport infrastructure, but increasing the efficiency in the provision of transport services and eliminating avoidable costs that emerge from sub-optimal policy making and/or weak institutional frameworks.

Reforms of the 90’s and Results in the Transport Sector. Since 1991, the Argentine economy was transformed through a broad set of reforms to embrace open market policies that redefined the role of the state and eliminated regulatory constraints to many private initiatives. Trade liberalization highlighted the relative importance of transport costs in determining international commerce flows and promoting country competitiveness. In search of efficiency gains, increased competition and improved service quality, the reforms introduced in the transport sector in particular, aimed to: (i) reduce the size and redefine the role of the public sector; (ii) establish private sector schemes for the rehabilitation and expansion of assets; and (iii) reduce the sector’s reliance on public budgets. Argentina launched a concession program involving all sub-sectors, deregulated many transport services, and reoriented transport agencies functions towards policymaking, planning, regulation and control.

The overall balance of the reform is positive, although it differs according to the level of competition and level of government intervention required in each sub-sector. Results in terms of coverage and quality of services are in general positive, whereas consumer gains in terms of price reductions were limited to those cases where competition clearly worked (i.e. ports). The need for adjustment has become evident as profound changes in the economic context,

4 Logistics costs are becoming increasingly relevant to international trade given the significant reduction in trade tariffs worldwide over the last decade unpredictable policy making, problems of governance and weak enforcement of contractual obligations, resulted in constant contract renegotiations and in some cases, assumption of considerable government liabilities (e.g. subsidies to compensate toll and tariffs reductions). Furthermore, the focus on the regulatory reforms of the 1990s program overlooked the strategic policy-making function of the State and the determination of strategic objectives. As a result, the long term planning efforts for the sector was somehow debilitated.

Consolidating and fine tuning the reforms of the nineties in terms of private sector participation, promoting intermodal integration, and establishing a governance system that encourages efficient planning policies, adequate resource allocation, transparency and social accountability, are at the core of the unfinished agenda to continue modernizing the sector, and on the whole, to reduce transport costs in the country. Given that road transport is the predominant mode of freight movement in Argentina, the implementation of efficient managerial, financial and investment practices in the road sub-sector is of utmost significance. For this reason, dealing with the main road sector issues to improve sector performance and sector management while expanding the benefits of these efforts to the poorer regions of the country is the main purpose of the proposed project.

Argentina’s Road SectorMain Characteristics and Recent Performance. Concentrating nearly 80% of total freight volume movements, the road sector is the dominant mode of transport in the country. Argentina has a relatively extensive road network managed by the Government that consists of: (i) an estimated 39,000 km of national roads (31,000 km paved) managed by the National Directorate of Highways (DNV); and (ii) 195,000 km of provincial roads under the jurisdiction of 23 Provincial Road Directorates (DPV) which serve as main collectors and connectors between the national network and productive regions.

The national road network system, built in its great majority more than 20 years ago represents assets that are valued at about US$ 7 billion equivalent. About 80% of the paved network consists of flexible structures with granular base, and the remainder is made mainly of soil- cement and occasionally bituminous macadam. There are about 2,100 bridges on the national highway system representing a total length of nearly 700 km of which 85% percent is more than 20 years old and has not received adequate maintenance over the last 15 years. Traffic volumes cover a wide range, from less than 500 vehicles per day up to 10,000 to 20,000 vehicles per day on the most heavily trafficked corridors.

The major expansion of the road network was initially funded through earmarked taxes (on fuels, tires, lubricants and vehicle registration and sales taxes), allocated directly to DNV and the existing DPV’s. During the 1970’s and 1980’s growing fiscal pressures increasingly diverted the road sector funds to meet other needs until finally, as part of the economic policy reform initiated in the late 80’s, revenues from taxes on petroleum, tires and lubricants were transferred directly to the Treasury and the earmarking of revenues from taxes on vehicle registration fees and sales was removed. Earmarked revenue assignments to DNV were eliminated leaving the sector subject to budgetary allocations from the general Treasury. Continued fiscal crises and deficient management policies in the 1980’s led to under-funding and deterioration of road assets to the point that, in 1990 Argentina had the lowest share of paved roads in good condition among upper-middle income countries. A survey carried out in 1992 confirmed that only 44% of the national paved network was in good condition, with a high 35% of roads in critical or poor condition.

Through the sector reforms introduced by the GoA in 1990, there was a shift towards enhancing private participation and almost 9,000 km of the highest trafficked roads (more than 2,500 vehicles per day) were concessioned to the private sector. A new entity (OCCOVI) was created to assume all decision-making responsibilities and to handle the inter-urban road concession contracts, even though the road network continued to be under DNV’s jurisdiction. Furthermore, the maintenance of some 10,000 km of the non-concessioned paved network was managed through performance-based contracts (CREMA5) introduced for the first time in the country in 1995. The remaining 12,000 km of the paved network was: (i) concessioned for a 10-year period under a non-tolled system called COT (600 km); (ii) maintained, subject to the availability of resources, through agreements with the DPV’s (5,000 km) and/or output-based routine maintenance contracts called km/month (4,400 Km); and (iii) left under the responsibility of DNV to perform Force-account activities (2,000 Km). Overall, the inter-urban road concessions achieved partially the objective of rehabilitating the core inter-urban national network and improving or maintaining the quality of service provided. However, this: (i) was achieved at a higher than expected cost and/or at expense of the potential benefits to the users; and (ii) resulted in the assumption of considerable government liabilities after a series of renegotiations that restructured fundamental features of the concession contracts (e.g. toll reductions, introduction of compensation payments, postponed investments). In 2003, these concessions expired and new Operational and Maintenance concession contracts were awarded for a much shorter period (5 years), placing on the Government the responsibility of financing and executing rehabilitation and upgrading works. The latter is a novel feature that has not been fully tested, and will require DNV’s strong leadership to avoid potential conflicts between concessionaires and construction firms.

The CREMA system proved to be a successful mechanism to maintain the network and ensure the continuity of works even during critical periods of the economic crisis. The system is being replicated with changes elsewhere. As a result of the crisis, during that period the CREMA contracts were extended in cases up to two years to prevent the deterioration of the network while a new bidding program is launched. For this reason, after seven years under CREMA, some of the roads under CREMA still need some minor rehabilitation works. Those segments of the non-concessioned network not under CREMA, currently in poor condition, require major interventions and continued maintenance. The proposed project aims at expanding the CREMA system to most of said network, so that by the end of the project, out of the 22,000 km of paved- non-concessioned roads, at least 16,676 km are managed through CREMAS. The remaining portion is to be managed through two-year ad-measurement type contracts (and 4,388 Km) and COT.

Today, the condition of the road network has improved considerably. The proportion of paved roads in poor condition (with IRI>5) has dropped to about 5%. On the concessioned network,

5 CREMA (Contrato de Recuperación y Mantenimiento) is a lump sum contract that requires a contractor to rehabilitate and maintain a network for a total of five years. Rehabilitation works are to be carried during the first 18 months, while maintenance activities are undertaken through out the contract period. The payment schedule is designed to ensure that the contractor maintains the network for the full length of the contract under a specified level of service. that percentage is insignificant. On the non-concessioned portion, the proportion of roads with IRI>4 is still in the order of 29%, of which 8% has IRI>5, particularly concentrated on areas with lower traffic volumes that have not been under CREMA.

Between 1993 and 2000, DNV’s annual budget allocations ranged between US$450 million and US$650 million6, distributed among investment expenditures (52%), debt service (38%), personnel, administrative costs and other (10%), leaving available resources for rehabilitation and maintenance at most in the range of US$230 million and US$330 million. Economic evaluations using the HDM model suggests that in order to preserve the entire non-concessioned paved network in a sustainable good to fair condition, future annual investment allocations should be at a level of about US$16,000 per km per year or about US$350 million.

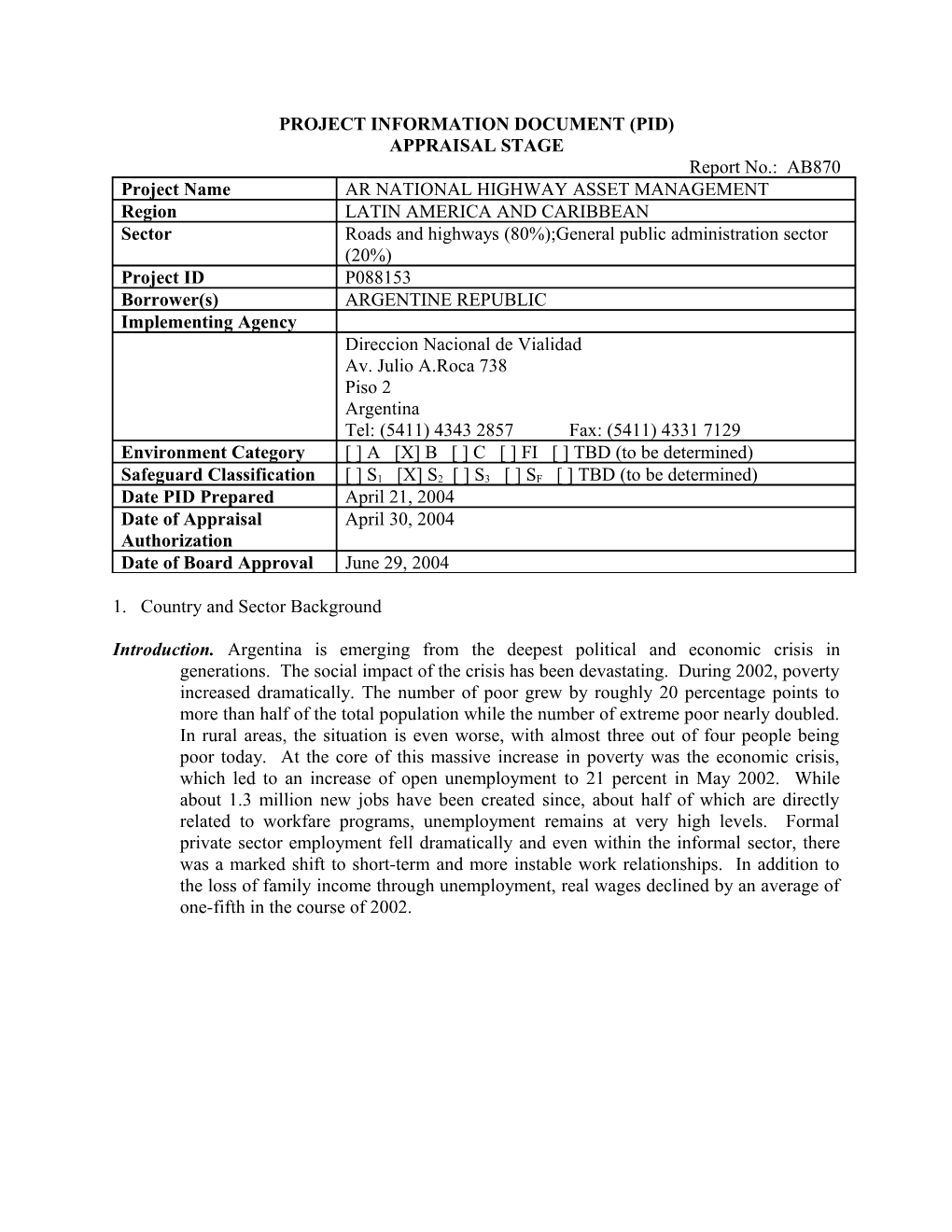

Table 1- DNV’s Annual Budget 2000-2004 (US$ Million)

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 CONCEPT Allocation Execution Allocation Execution Allocation Execution Allocation Execution Allocation Investment 295 227 231 183 132 90 158 137 286 Debt Service 244 209 141 122 79 78 98 81 134 Personnel, Administrative Costs and Other 102 92 94 61 35 32 24 23 38 TOTAL BUDGET 641 528 467 365 247 200 280 241 458

In 2001, the GoA attempted to implement a new road financing system with the idea of expanding private participation through different private/public arrangements. The GoA approved a surcharge on diesel7 to support the creation of a Transport Infrastructure Trust Fund (Fondo Fiduciario del Gasoil) initially intended to: (i) use the first two years of revenues to pay- off the debt accumulated on the concessions expiring in 2003 (an therefore avoid extending them), and (ii) use the revenues from year 2003 onwards to finance new road investments through its main component, the SISVIAL (receiving 80% of total proceeds). The remaining 20% was allocated to what was called the SISTRAN aimed to finance the railway sector. However, the SISVIAL mechanism was never established. The Transport Infrastructure Trust Fund had its allocation rules modified five times in the space of 12 months by a series of Decrees and Ministerial Resolutions, incorporating new beneficiaries and changing its institutional location. At the end, after the outstanding debt with the previous concessionaires was eliminated, the funds were increasingly assigned to finance subsidies to national and provincial bus operators, and urban transport services8. Investment decision-making regarding this Fund (administered by the UCOFIN -Unidad de Coordinación de Fideicomisos de Infraestructura) is out of the control of DNV, pending joint resolutions from the Minister of Infrastructure and the Minister of Economy, leaving a wide uncertainty concerning its applicability in the road sector, albeit being an important and stable source of funding.

Government’s new strategy for the road sector: The new administration’s vision for the future includes: (i) operating and maintaining high traffic highways through toll road concessions, leaving planning and execution responsibilities for upgrading/rehabilitation activities within

6 In the economic crises (1990-1992 and 2002-2003), budget allocations dropped to the level of US$200 million. 7 Initially being a specific tax of $0.05 per liter of diesel but later modified to an ad valorem 18.5%. 8 Over the years, the allocation to the SISVIAL was reduced to 60% increasing the participation of the SISTRAN to 40% and more recently, changed again to 50%-50%, to maintain an ever-increasing subsidy scheme to transport service operators (passengers and cargo). those corridors to DNV; (ii) consolidating a long-term maintenance strategy for the non- concessioned paved national road network (22,000 km) through the gradual expansion of the CREMA system; (iii) elevating the DNV’s role within the sector, in particular re-orienting its capacity towards the strategic planning of the primary road network (including the concessioned portion) and promoting a more coherent vision for the entire road network across other government jurisdictions; (iv) prioritizing investments in bridge rehabilitation, modernizing its bridge management strategy; and (v) improving road safety. The broader strategy to link the road sector with other infrastructure sub-sectors will be the “Strategic Plan for Territorial Development” the elements of which are being developed. The GoA has requested the Bank to support this strategy, as a first step towards implementing its transport sector agenda.

Rationale and Issues to be Addressed: To bring about this vision, there are some specific issues that are closely intertwined and need to be addressed simultaneously:

Gradually moving towards a steady-state condition of the road network. Currently, the road network requires important periodic maintenance and rehabilitation interventions to upgrade its overall condition. This implies higher financial requirements than those under a steady-state scenario where the network deterioration reaches a relatively constant level year after year and future interventions can be anticipated and reasonably taken care of with existing resources. Expanding the CREMA system is a step in this direction but implies securing the necessary funds to rehabilitate segments that have not received interventions in the last years, implementing adequate planning strategies to anticipate future requirements, and elaborating efficient work programs that are aligned with existing budgets.

Putting in place adequate road financing strategies to guarantee the sustainability of the road sector within a given fiscal framework. One of the most pressing needs is to design and implement a sound system for the financing of the road network in which resource allocation is based on cost-effective policies according to agreed and coherent priorities. Ideally, predictable and dependable sources of funding available to the sector, such as those accumulated in the Transport Infrastructure Trust Fund, should be redirected towards the maintenance of the network, while the approval of new construction works reflects the treasury budget allocations within a given fiscal space. Currently, the GoA is considering using the Transport Trust Fund to: (i) finance upgrading/rehabilitation works agreed under the recently awarded concession contracts, and (ii) complement budgetary allocations to expand DNV’s CREMA program, at least during a transition period while the steady-state situation is achieved. DNV plays an essential role in the execution of these two tasks, but to ensure an adequate performance in the fulfillment of its obligations, stable and timely funding is crucial. However, as previous experience has shown, the allocation rules of the Transport Trust Fund can be easily modified leaving a wide uncertainty concerning its applicability, and rising governance issues that need to be tackled.

From a macroeconomic perspective, extra-budgetary funds are regarded as problematic because they limit the required flexibility to optimally allocate scarce resources among competing needs and may not follow the same scrutiny and accountability standards as the general budget. But from a microeconomic perspective, a fund comprising user charges, that follows well accepted and strongly advisable “user pays” principles, reduces the vulnerability of the flow of funds due to fiscal downturns9. In any case, if the GoA decides that this financing mechanism is to continue playing an important role in the sector, more transparent and better rules governing the allocation of funds and mechanisms to ensure accountability are required. Also, suitable governance arrangements are needed to ensure that funds are effectively protected and used. The project would finance a study to analyze the above- mentioned issues, examining the different sources of funds available to the sector, recommending ways to optimally allocate them and proposing alternatives to ensure the financial stability of the road sector in the long run.

Overcoming the institutional meltdown that undermined the authority of the road agency and induced the adoption of ad-hoc policies, such as carving away from the scope of the DNV: (i) decisions regarding the concession network and having an unclear distribution of responsibilities between DNV and OCCOVI; or (ii) decisions regarding the allocation of resources from the Transport Trust Fund (with increased uncertainty resulting from frequent changes in the principles and rules defining the allocation of resources). The DNV needs to be invigorated to regain its muscle within the sector, becoming the strategic planner of the primary road network and consolidating its transformation into a client-oriented organization. The successful institutional renovation of the road agency requires transformations based on basic principles of efficiency, transparency and accountability with the overarching GoAl to:

i. Increase Transparency through: (i) the development of a system that clearly establishes what is being achieved, at what cost, and how that cost compares with internationally accepted benchmarks; (ii) the validation of the information through credible auditing measures and disseminate that information widely; (iii) the establishment of clear links between sources and uses of funds, on the basis of technical parameters relating the cost of providing a certain level of service to a particular network. ii. Create Accountability for Outcomes emphasizing the fulfillment of promises and enforcement of performance. Establish a clear system of incentives for performance improvements and target-oriented programs. iii. Improve Mechanisms for Establishing Investment Priorities through the promotion of an integrated vision of the road network, based upon objective planning criteria.

The weak institutional coordination and lack of leadership to achieve the integration of the road networks under all jurisdictions to achieve an effective reduction of transport costs and an increase in the productivity and competitiveness of local products in international markets. Given the nature of the economic activity in the country there is a structural need to integrate key transport networks among different jurisdictions to effectively connect ports and the main production and consumption centers. To this end, it is essential to devote time and resource-consuming efforts to prepare coordinated road

9 A detailed analysis of this issues is presented in the World Bank Economic Report 25991-AR: “Argentina- Reforming Policies and Institutions for Efficiency and Equity of Public Expenditures”, September 10, 2003. development plans based on unified national objectives. This issue would be addressed under the umbrella of the Strategic Plan for Territorial Development, (“Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial Estratégico”) which is being prepared by the SOP, and would be supported under the proposed project.

Improving road safety standards. Argentina’s road network faces a serious issue of road safety, revealing a road crash fatality rate (deaths per population) three times greater than the current rate of best practice countries (Sweden, United Kingdom and the Netherlands). Even at regional standards, Argentina heads the ranking for Latin American countries, with an average rate of 20 deaths per day, 1,377 life losses in 2003, 120,000 injuries or disabilities per year and 11.08 deaths per 100 million kilometers traveled. Considering that World Bank studies predict that fatality rates for LAC region will, by 2020, increase at least by 50%, if road safety measures are not taken urgently, the trend in Argentina will deteriorate significantly. It is estimated that Argentina could, by year 2020, present a fatality rate at least 10 times greater than the rate of best practice countries in Europe, strongly aggravating the development disparity.

Gradually bring up and align the condition of the bridges to that of the roads. At present the system of bridges in Argentina, most of them more than 30 years old, are in a serious state of disrepair. The rather limited interventions that take place each year are selected on an ad-hoc basis, with a strong reliance on visual methods and personnel with a strong institutional memory. DNV is now planning, with the support of the Bank, to develop and implement a Bridge Management System to systematically follow up on bridge conditions and to allocate scarce resources based on sound technical and economic criteria.

2. Objectives

The overall purpose of the project is to consolidate an efficient road network management strategy, bringing about the necessary resources to preserve the national road network in the long term. This is a key condition towards increasing the competitiveness of the economy and supporting a sustainable path of economic growth and poverty reduction. The proposed project builds on the achievements of the ongoing Bank-assisted 4295-AR National Highways Rehabilitation and Maintenance Project and would have the following specific objectives:

a. Preserve the condition of vital road assets, through the gradual expansion of performance-based contracts for the rehabilitation and maintenance of the non-concessioned primary paved network; b. Strengthen road sector management through carrying out a renewal program of DNV to revitalize its role in the sector by: (i) reinforcing its human resource base; and (iii) consolidating its transformation into a results-oriented organization accountable for specific outputs (e.g. preserving transitability and adequate road conditions, enhancing road safety, promoting integration, etc.). Achievement of Project Development Objectives will be confirmed through the following key indicators: (i) percentage of paved non-concessioned network under CREMA system; (ii) roughness of paved non-concessioned netwok will not exceed IRI of 3.8; (iii) DNV having effectively implemented the Institutional Renewal Action Plan.

Expanding the CREMA program to other regions of the country would help to decrease disparities in terms of transport investment, in favor of poorer areas that are less economically active, fostering regional productivity via the reduction of logistic costs between potentially productive areas, consumption areas and main ports (facilitating access to markets). In particular, the proposed project would benefit people in rural and low-income areas through: (i) the reduction of time and travel costs, (ii) new employment opportunities (4,000 new jobs in 5 years) as many of the rehabilitation and maintenance activities require unskilled labor for carrying out the works and for the production of materials (cement, asphalt), (iii) increased competitiveness and development of labor generating productive activities (e.g SMEs) and (iv) improved access to basic services.

The Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) seeks to reduce the extent and severity of poverty in Argentina by focusing on: (i) promoting sustained economic growth with equity; (ii) social inclusion; and (iii) improved governance. It emphasizes that one of the building blocks for sustained economic growth is maintaining and improving key infrastructure assets that facilitate regional development and the inclusion of Argentina in a globalized economy.

The overall and specific objectives of this project are consistent with the above pillars since as was mentioned before, maintaining and improving the road network is a means to foster regional productivity and competitiveness, and hence supporting the path towards sustained economic growth. At the same time, the project will seek to expand the CREMA system to those areas that have not been rehabilitated in the past years, thus targeting poorer regions that are not well integrated into the national economy. Finally, initiatives to increase governance, accountability and transparency in the road sector are being considered in the project through the institutional renewal component.

3. Rationale for Bank Involvement

The World Bank has played a key role in the road sector in Argentina, reducing the rehabilitation and maintenance backlog on both the national and provincial networks and supporting institutional transformation processes to improve road management and enable rationalization of road expenditures in the country. In particular, through Loans 3611-AR and 4295-AR the Bank assisted DNV in the pioneer initiative to develop and implement CREMA-type contracts, establishing clear and transparent rules in its design and awarding, and providing stable flows of funds even during severe fiscal crises. Through Loan 4093-AR the Bank has supported the development of efficient provincial road programs, gradually transferring maintenance execution to private contractors or to local road consortia, and strengthening the environmental management capabilities of the DPVs. Bank involvement in this project would further improve the results achieved so far by: Supporting the expansion of CREMA contracts on roads that, due to recent fiscal restrictions, have not been adequately maintained and require high initial rehabilitation investments, as a means to support a strategy in which a steady state condition would gradually be reached. Promoting a policy dialogue to improve the financial sustainability of the road sector Rationalizing highway expenditures and programs based on technical and economic criteria by emphasizing maintenance and improving cost recovery, increasing transparency and accountability. Supporting DNV’s renewal process as a user-oriented agency with clear gols, integrated information systems and strategic planning tools, systematic use of performance management systems, and ability to plan, contract out and monitor road operations. Bringing worldwide knowledge and best practices to prepare a large-scale initiative on road safety Insert the road sector planning within a territorial development framework.

4. Description

Component 1 – Rehabilitation and Maintenance (Estimated cost US$760 million of which US$350 million would be financed by the Bank Loan). Through this component, the Bank would support the expansion of DNV’s CREMA Program, which aims to expand the use of performance-based contracts to maintain its entire paved non-concessioned network. In particular, this component would finance the execution of works under the CREMA system on about 9.936 km, which are being designed so as to include important rehabilitation and maintenance works (on average 82% of total costs correspond to capital investment expenditures for rehabilitation works) particularly in those segments that did not receive adequate maintenance recently due to fiscal restrictions, to overcome a backlog of deferred maintenance and bring the infrastructure back to full productivity(approximately 65% of these roads are entering the CREMA program for the first time). Most of these networks have been/are being procured under Loan 4295-AR. DNV will continue financing CREMA contracts on some additional 6,740 Km and will also finance two-year ad-measurement type contracts on the remaining 4.388 Km. Overall, during project implementation a total of 16,676 km (out of 22,000 km) are to be maintained through performance-based contracts.

Component 2 – Bridge Restoration (Estimated cost US$33 million of which US$25 million would be financed by the Bank Loan). Given recent budgetary restrictions, DNV has not been able to properly take care of its bridges and has only performed emergency interventions on specific points. So far, DNV has slated about 65 bridges for attention in the next five years, some of which are in critical condition and need to be urgently repaired under the project. Works would include construction, reconstruction, replacement, widening and rehabilitation activities, to be carried out within the existing right-of-way. A comprehensive bridge management tool to systematically prioritize bridge interventions and identify cost-effective solutions would also be financed.

Component 3- Road Safety (Estimated cost US$27 million of which US$20 million would be financed by the Bank Loan). This component would support the implementation of recommended actions that evolved from a Road Safety Technical Assistance financed by the Bank (under Loan 3611-AR). Two sub-components are being considered: (i) a large-scale pilot initiative integrating engineering, enforcement and education measures over 4 pilot corridors, with an overarching objective of demonstrating the effectiveness of an integrated, results-focused road safety program and help create the knowledge, experience and commitment required to roll it out successfully throughout the rest of the country; and (ii) road safety engineering interventions on identified black spots of the road network across the country, targeting areas with high concentrations of crash fatalities, mainly near urban centers.

Component 4- Institutional Renewal (Estimated cost US$5 million). The project would provide technical assistance to: (i) develop and implement a human resources plan to rebuild DNV’s technical and institutional capacity within its new envisioned role as strategic planner of the road network performing under a results-oriented framework; (ii) facilitate DNV’s technological modernization to increase its productivity and strengthen its planning, supervision, and monitoring capabilities; (iii) streamline time consuming administrative processes to achieve efficiency gains in the internal management of the entity; (iv) design transparency mechanisms to disseminate DNV’s administrative, operational and financial performance, generalizing the use of performance indicators to enhance accountability, utilizing external agents to monitor performance and control results, and constructing performance and user satisfaction indicators that help visualize the achieved results; (v) strengthen DNV’s capacity for addressing environmental issues throughout the project cycles; (vi) analyze options for ensuring long term financial sustainability in the road sector and stable flows of funds for road maintenance and (v) the development and implementation of the Strategic Plan for Territorial Development. The project is preparing twinning arrangements with road agencies from other countries as a vehicle to providing key technical assistance.

5. Financing Source: ($m.) BORROWER 425 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND 400 DEVELOPMENT Total 825

6. Implementation

a. Executing Agencies. The Ministry of Economy would be the Government’s Borrower. Under a separate subsidiary agreement between Ministry of Economy and DNV, DNV would be appointed as the executing agency and would be responsible for carrying out most of the project activities. b. Project Management. The Project Coordinating Unit (PCU) established within DNV for implementation of the 3611-AR and 4295-AR loans will remain in charge of coordinating project activities. The PCU has a proven track record in managing projects for the World Bank and the IDB, having acquired expertise in procurement, disbursements, environmental and social guidelines, and auditing requirements. With full implementation of measures presented in Annex 7 (FM Action Plan) and Annex 8 (Procurement), DNV would have in place enhanced arrangements to meet the Bank’s fiduciary and procurement requirements for the proposed project. The incremental project costs of the unit will be financed under the project.

7. Sustainability

Project sustainability in the long-run depends on the implementation of cost-effective solutions to maintain the network so as to reach a steady-state condition where annual needs become manageable; transforming DNV into a high performance organization with increased accountability for outcomes; ensuring stable road sector funding; and institutionalizing a culture of road safety.

The project would pursue sustainability by: (i) furthering key institutional reforms in DNV to make the organization more efficient and responsive to client needs under a results-oriented framework; (ii) using the HDM-4 models both at headquarters and regional offices and the Bridge Management System to carry out the road and bridge maintenance and rehabilitation programs; (iii) expanding the CREMA system to rehabilitate and maintain the paved non- concessioned portion of the network securing the required funds through the next five years and reducing future annual costs; (iv) testing ways to develop an integrated approach to road safety; and (v) exploring mechanisms to enhance road sector financing in the long run and (vi) assisting in the development of the strategic plan for territorial development. Through the institutional renewal component, the project would assist the Secretary of Public Works and DNV in devising mechanisms to ensure efficiency and accountability in the ways funds are allocated into different programs. A study on road sector financing issues will be financed, to analyze among other aspects, the best options for ensuring a stable flow of funds for road maintenance.

8. Lessons Learned from Past Operations in the Country/Sector

Cost Overruns/Delays in implementation. Prior to the introduction of the CREMA system of contracting road maintenance, the highway projects financed by the Bank in Argentina were generally flawed with the problems of substantial cost overruns and considerable delays in implementation. Apart from the bursts of high inflation and rapid devaluation that aggravated the delays and cost problems, these were mostly due to inadequate and untimely designs, the ad- measurement type of contracting, and the shortages of counterpart funds. The fixed-price and fixed-term CREMA system used over the last 7 years in Argentina combined with the requirement made to the Contractor to prepare detailed engineering designs before initiating the works, has shown that there has been no cost overrun except for the unpredictable variation orders due to unforeseen events (“eventos compensables”) which altogether represented less than 4% increase in costs over the life of the contracts. The proposed project replicates this successful experience. Delays in disbursements for this project should be minimal since most of the CREMA contracts financed under the proposed loan, will have been tendered and awarded during this calendar year or at the beginning of the next one.

Counterpart funding and budgets. Historically, due to Government’s efforts to contain public expenditures in order to achieve economic stabilization, counterpart-funding problems have adversely impacted the implementation of the physical investment components of most highway projects in Argentina. Under the CREMA contracts, the long-term payment obligations become legally binding on the Government and as a result, the budgetary process has given these contracts a higher priority than other expenditures. Also, such contracts between the Government and private operators that involve financial risks for the operator appear to be given priority in budgetary allocations in countries that are seeking a broader role for the private sector and may be the way to secure a more adequate and more reliable funding mechanism for highway maintenance. The experience has demonstrated that CREMA contracts get a higher priority in budgetary allocations than traditional methods for executing maintenance (ad-measurement type of contracts or force-account). Therefore, by expanding the CREMA system, the risks of shortages of maintenance funds are substantially reduced.

Lessons learned from previous projects design. Based on previous experiences, a few modifications have been introduced to the new CREMA contracts, to include for instance, some road safety measures as compulsory works (horizontal and vertical signaling, protection barriers, upgrading urban crossways and intersections) and requiring contractors to prepare detailed environmental management plans.

Design and implementation of the institutional component. It is generally recognized that Borrowers and Executing agencies, in most Bank-financed projects, tend to give higher priority to physical investments than to the institutional component, which often fall short of achieving their objectives. This has been particularly true for the two previous and on-going highway projects. In Loan 3611 (1993-1998), project amendments successively reduced project funding for studies, consultants and training from US$ 30 million to US$ 12 million, due to reluctance by DNV to utilize these funds for Technical Assistance and also due to reduced government ownership of this component. Likewise, under the on-going 4295-AR loan, even a much reduced allocation of US$ 13 million that was earmarked for training, seminars, staff exchange programs and studies has barely been used (nine months away from the closing date, only US$ 500,000 have been disbursed). The proposed project reflects this lesson by allocating US$ 5 million to this component, focusing on a few achievable goals with a high level of ownership. Most of these funds will be used for the institutional renewal and empowerment of DNV, an objective for which the executing agency has strong incentives. Also, given the current limitations to hire foreign consultants, twinning arrangements with international road agencies are envisaged to implement some of the proposed activities.

9. Safeguard Policies (including public consultation)

Safeguard Policies Triggered by the Project Yes No Environmental Assessment (OP/BP/GP 4.01) [X ] [ ] Natural Habitats (OP/BP 4.04) [ ] [X ] Pest Management (OP 4.09) [ ] [X ] Cultural Property (OPN 11.03, being revised as OP 4.11) [ ] [X ] Involuntary Resettlement (OP/BP 4.12) [ ] [X ] Indigenous Peoples (OD 4.20, being revised as OP 4.10) [ ] [X ] Forests (OP/BP 4.36) [ ] [X ] Safety of Dams (OP/BP 4.37) [ ] [X ] Projects in Disputed Areas (OP/BP/GP 7.60)* [ ] [X ] Projects on International Waterways (OP/BP/GP 7.50) [ ] [X ]

10. List of Factual Technical Documents

1. DNV 2004. Environmental Assessment Report

11. Contact point Contact: Maria Marcela Silva Title: Transport. Spec. Tel: (202) 473-2092 Fax: Email: [email protected]

12. For more information contact: The InfoShop The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20433 Telephone: (202) 458-5454 Fax: (202) 522-1500 Web: http://www.worldbank.org/infoshop

* By supporting the proposed project, the Bank does not intend to prejudice the final determination of the parties' claims on the disputed areas