A Short History of Horkstow and the Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Central Lincolnshire Settlement Hierarchy Study Sep 2014

PRELIMINARY CENTRAL LINCOLNSHIRE SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY STUDY September 2014 (Produced to support the Preliminary Draft Central Lincolnshire Local Plan) CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Policy Context 1 3. Methodology 2 4. Central Lincolnshire’s Settlements 2 5. The Settlement Categories 3 6. The Criteria 4 7. Applying the Criteria 6 8. Policy and ‘Localism’ Aspirations 9 9. Next Steps 9 Appendix: Services and Facilities in 10 Central Lincolnshire Settlements 1. Introduction 1.1. A settlement hierarchy ranks settlements according to their size and their range of services and facilities. When coupled with an understanding of the possible capacity for growth, this enables decisions to be taken about the most appropriate planning strategy for each settlement. 1.2. One of the primary aims of establishing a settlement hierarchy is to promote sustainable communities by bringing housing, jobs and services closer together in an attempt to maintain and promote the viability of local facilities and reduce the need to travel to services and facilities elsewhere. A settlement hierarchy policy can help to achieve this by concentrating housing growth in those settlements that already have a range of services (as long as there is capacity for growth), and restricting it in those that do not. 1.3. In general terms, larger settlements that have a higher population and more services and facilities are more sustainable locations for further growth. However, this may not always be the case. A larger settlement may, for example, have physical constraints that cannot be overcome and therefore restrict the scope for further development. Conversely, a smaller settlement may be well located and with few constraints, and suitable for new development on a scale that might be accompanied by the provision of new services and facilities. -

Lincoln in the Viking Age: a 'Town' in Context

Lincoln in the Viking Age: A 'Town' in Context Aleida Tessa Ten Harke! A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield March 2010 Volume 1 Paginated blank pages are scanned as found in original thesis No information • • • IS missing ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of Lincoln in the period c. 870-1000 AD. Traditional approaches to urban settlements often focus on chronology, and treat towns in isolation from their surrounding regions. Taking Lincoln as a case study, this PhD research, in contrast, analyses the identities of the settlement and its inhabitants from a regional perspective, focusing on the historic region of Lindsey, and places it in the context of the Scandinavian settlement. Developing an integrated and interdisciplinary approach that can be applied to datasets from different regions and time periods, this thesis analyses four categories of material culture - funerary deposits, coinage, metalwork and pottery - each of which occur in significant numbers inside and outside Lincoln. Chapter 1 summarises previous work on late Anglo-Saxon towns and introduces the approach adopted in this thesis. Chapter 2 provides a discussion of Lincoln's development during the Anglo-Saxon period, and introduces the datasets. Highlighting problems encountered during past investigations, this chapter also discusses the main methodological considerations relevant to the wide range of different categories of material culture that stand central to this thesis, which are retrieved through a combination of intrusive and non-intrusive methods under varying circumstances. Chapters 3-6 focus on funerary deposits, coinage, metalwork and pottery respectively, through analysis of distribution patterns and the impact of changes in production processes on the identity of Lincoln and its inhabitants. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. HAB 621 Swift Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY .J LINCOLNSHIRE. HAB 621 Swift Mrs. Caroline, Mort<ln Bourn Ward George, Keal Coates, Spilsby Wilson Robert, Bas!lingham, Newark tSwift W. E.Lumley rd.SkegnessR.S.O Ward John, Anderby, Alford Wilson William, 142 Freeman street, Taft David, Helpringham, Sleaford tWard Thomas, 47 Market pl. Boston Great Grimsby Talbot Mrs. Elizh. Ba':!singham, Newark Ward Wm. jun. Great Hale, Sleaford Winn Misses Selina Mary & Margaret Tate Henry, SouthKillingholme, Ulceby Ward Wm.Ailen,Hillingboro',Falkinghm Ellen, Fulletby, Horncastle TateJobn H.86 Freeman st.Gt.Grimsby Wardale Matt. 145 Newark rd. Lincoln Withers John Thomas, I03 'Pasture Tayles Thomas, 55 East st. Horncastle tWarren Edward, Little London, Long itreet, Weelsby, Great Grimsby TaylorMrs.AnnM.2 Lime st.Gt.Grimsby Sutton, Wisbech Withers J. 26 Pasture st. Great Grimsby TaylorGeo. Wm. Dowsby, Falkingham WarsopM.North st.Crowland,Peterboro' Withers Sl. 66 Holles st. Great Grimsby Taylor Henry, 6o East street, Stamford WassJ.T.Newportst.Barton-on-Hurnber Wood & Horton, 195 Victor street, New Taylor Henry, Martin, Lincoln Watchorn E. Colsterworth, Grantham Clee, Great Grimsby Taylor Henry, Trusthorpe, Alford Watchorn Mrs. J. Gt. Ponton,Grantham Wood Miss E. 29 Wide Bargate, Boston Taylor John T. Burringham, Doncaster Waterhouse Alex.I Spital ter.Gainsboro' Wood E. 29 Sandsfield la. Gainsborough Taylor Mrs. Mary, North Searle,Newark Waterman John, Belchford, Horncastle ·wood Hy. Burgh-on-the-Marsh R.S.O Taylor Mrs. M.3o St.Andrew st. Lincoln Watkin&Forman,54Shakespear st.Lncln Wood John, Metheringham, Lincoln Taylor Waiter Ernest,I6 High st. Boston WatkinJas.44 & 46 Trinity st.Gainsboro' Woodcock Geo. 70 Newark rd. -

A New Beginning for Swineshead St Mary's Primary School

www.emmausfederation.co.uk Admission arrangements for Community and Voluntary Controlled Primary Schools for 2018 intake The County Council has delegated to the governing bodies of individual community and controlled schools the decisions about which children to admit. Every community and controlled school must apply the County Council’s oversubscription criteria shown below if they receive more applications than available places. Arrangements for applications for places in the normal year of intake (Reception in Primary and Infant schools and year 3 in Junior schools) will be made in accordance with Lincolnshire County Council's co‐ordinated admission arrangements. Lincolnshire residents can apply online www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions, by telephone or by requesting a paper application. Residents in other areas must apply through their home local authority. Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools will use the Lincolnshire County Council's timetable published online for these applications and the relevant Local Authority will make the offers of places on their behalf as required by the School Admissions Code. In accordance with legislation the allocation of places for children with the following will take place first; Statement of Special Educational Needs (Education Act 1996) or Education, Health and Care Plan (Children and Families Act 2014) where the school is named. We will then allocate remaining places in accordance with this policy. For entry into reception and year 3 in September we will allocate places to parents who make an application before we consider any parent who has not made one. Attending a nursery or a pre-school does not give any priority within the oversubscription criteria for a place in a school. -

St•John Passion

Issue 31: Winter edition 2016 the Journal of the Lincoln Cathedral Community Association InHouseJ. S. BACH Cathedral’s ST•JOHN published poets Page 7 PASSION Page 5 Sat 12 March 2016 | 7pm in the Nave of Lincoln Cathedral Lincoln Cathedral Choir Baroque Players of London A fond farewellLeader, Nicolette Moonen Judi Jones Jeffrey Makinson Director Aric Prentice Alto Matthew Keighley Arias Božidar Smiljanić Christus & Bass Mark Wilde Evangelist Tom Stockwell Pilate Eleanor Gregory Soprano Tickets £20.00 and £15.00 | 01522 561644 www.lincolncathedral.com/shop St John Passion Advert A5 V2.indd 1 05/11/2015 15:12 “A wonderful calm presence”; “He and Linda have been brilliant ambas- Sundays ago. The most common senti- has reminded us of the importance of sadors for our cathedral”. ment of all, uttered many times, was how prayer”; “An exceptionally able and These are just a few random, but heart- much we will miss them both. So January effective administrator”; “His erudite felt, comments about our Dean, the Very 31st 2016, the day that he retires, will be sermons always make me think and I Reverend Philip Buckler, and his wife a sad one for our congregation and the enjoy his poetic references”; “He has Linda, made by members of the congre- cathedral as a whole. been a steady hand at the helm”; “He gation after the 9.30am Eucharist a few CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 2 Farewell, Mr Dean Judi Jones Speaking to Philip last month, I asked well as in death. does behind the scene.” She told me that him what his concerns were nine years Both Philip and Linda have loved their she loved living in their house and has ago, before he took up his new role as time in Lincoln and feel that they have been happy entertaining guests there the 83rd Dean of Lincoln. -

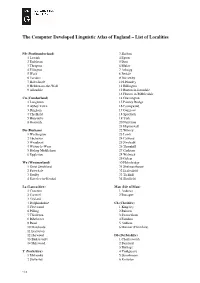

The Computer Developed Linguistic Atlas of England – List of Localities

The Computer Developed Linguistic Atlas of England – List of Localities Nb (Northumberland) 3 Skelton 1 Lowick 4 Egton 2 Embleton 5 Dent 3 Thropton 6 Muker 4 Ellington 7 Askrigg 5 Wark 8 Bedale 6 Earsdon 9 Borrowby 7 Haltwhistle 10 Helmsley 8 Heddon-on-the-Wall 11 Rillington 9 Allendale 12 Burton-in-Lonsdale 13 Horton-in-Ribblesdale Cu (Cumberland) 14 Grassington 1 Longtown 15 Pateley Bridge 2 Abbey Town 16 Easingwold 3 Brigham 17 Gargrave 4 Threlkeld 18 Spofforth 5 Hunsonby 19 York 6 Gosforth 20 Nafferton 21 Heptonstall Du (Durham) 22 Wibsey 1 Washington 23 Leeds 2 Ebchester 24 Cawood 3 Wearhead 25 Newbald 4 Witton-le-Wear 26 Thornhill 5 Bishop Middleham 27 Carleton 6 Eggleston 28 Welwick 29 Golcar We (Westmorland) 30 Holmbridge 1 Great Strickland 31 Skelmanthorpe 2 Patterdale 32 Ecclesfield 3 Soulby 33 Tickhill 4 Staveley-in-Kendal 34 Sheffield La (Lancashire) Man (Isle of Man) 1 Coniston 1 Andreas 2 Cartmel 2 Ronague 3 Yealand 4 Dolphinholme Ch (Cheshire) 5 Fleetwood 1 Kingsley 6 Pilling 2 Rainow 7 Thistleton 3 Swettenham 8 Ribchester 4 Farndon 9 Read 5 Audlem 10 Marshside 6 Hanmer (Flintshire) 11 Eccleston 12 Harwood Db (Derbyshire) 13 Bickerstaffe 1 Charlesworth 14 Halewood 2 Bamford 3 Burbage Y (Yorkshire) 4 Youlgreave 1 Melsonby 5 Stonebroom 2 Stokesley 6 Kniveton 1 | 4 7 Sutton-on-the-Hill 7 Sheepy Magna 8 Goadby Nt (Nottinghamshire) 9 Carlton Curlieu 1 North Wheatley 10 Ullesthorpe 2 Cuckney 3 South Clifton R (Rutland) 4 Oxton 1 Empingham 2 Lyddington L (Lincolnshire) 1 Eastoft He (Herefordshire) 2 Saxby 1 Brimfield 3 Keelby -

Lincolnshire

662 SHO LINCOLNSHIRE. SHOPKEEPERS continued. Coy William, East Butterwick, Doncastr Dobson William, West wood side, Bawtcy Cheeseman Mrs. Mary, Humberstone, Crabtree Mrs. H.Westgate,Belton,Dncstr Dodd John, Ancaster, Grantham Great Grimsby Crackle William, .Althorpe, Doncaster Dodds Gad, Friskney, Boston Cheetham Mrs.Jane,Marston,Grantham Cragg John, Northgate, Sleaford Dolby Mrs.Ann,GreatGonerby,Granthm Chessman William, Apley, Wragby CramptonGeorge,LittleLondon,Spaldng Dol by Robert, 48 Chelmsford st. Lincoln Chester David Fountain, Haven bank, Crampton Thos. 7 Tattershall rd.Boston Donaby Richard, 17 'fhomas st. Lincoln Wildmore, Boston Cranfield Jn. West Pinchbeck, Spalding Donnelly Michael,NewBoultham,Lincoln Chester Mrs. F. Winsover rd. Spalding Craven Wm. South Witham, Grantham Donnor Mrs.M.Ferry Corner plot, Boston Chesterton Mrs. Mary, Eastgate, Bourn Credland Mrs. A. Morton-by-Gainsboro' Dook Henry, Stow, Lincoln Chevins Peter R. 4 Canwick rd. Lincoln Credland George, 10 Oxford street, New Douglas Joseph, 71 Newark rd. Lincoln Chevins Waiter, Crais-e Lound, Bawtry Glee, Great Grimsby Dracass Wm. Andrw. Stickford, Boston ChiffingsMrs.K.We.'forrington,Wragby Credland Joseph, 8 North st. Grantham DraytonWilkinsonHy.14Pelhamst.Lncn Child Mrs. Ann, 31 High street, Lincoln CresseyWm. Thos.Scunthorpe,Doncaster Drayton William,Burringham,Doncaster Child Mrs. Elizh. 46 Ripon st. Lincoln Croft Mrs. E. High st. Wainfleet R.S.O Dring George,Burton Coggles,Grantham Christopher Miss A. Heckington,Sleaford Croft George, Thimbleby, Horncastle Dring Wm. South Witham, Grantham Clark Caleb, 4 Queen street, Brigg Croft Mrs. Sarah, Riverhead, Louth Drinkall George, Goxhill, Hull Clark Robert, Manthorpe, Grantham Croft William, I Harold ter. Grantham Driver Miss Fanny, 166 Eastgate, Louth Clark Mrs. S. -

Central Lincolnshire Water Cycle Study - Detailed Strategy

Water City of Lincoln, West Lindsey District Council June 2010 & North Kesteven District Council Central Lincolnshire Water Cycle Study - Detailed Strategy Prepared by: Christian Lomax Checked by: Clive Mason Principal Consultant Technical Director Approved by: Andy Yarde Regional Director Central Lincolnshire Water Cycle Study - Detailed Strategy Rev No Comments Checked by Approved Date by 3 Final Report CM AY June 10 2 Final Draft Report CM AY May 10 1 Second draft for comment CM AY Apr 10 0 Draft for comment RL AY Feb 10 5th Floor, 2 City Walk, Leeds, LS11 9AR Telephone: 0113 391 6800 Website: http://www.aecom.com Job No 60095992 Reference Rev3 Date Created June 2010 This document is confidential and the copyright of AECOM Limited. Any unauthorised reproduction or usage by any person other than the addressee is strictly prohibited. f:\projects\rivers & coastal - lincoln water cycle study phase 2\04_reports\03_draft detailed strategy\lwcs detailed strategy final report.doc AECOM Central Lincolnshire Water Cycle Study - Detailed Strategy 0 Table of Contents Non-Technical Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Future Growth & Development ........................................................................................................................................... -

Lincolnshire Remembrance User Guide for Submitting Information

How to… submit a war memorial record to 'Lincs to the Past' Lincolnshire Remembrance A guide to filling in the 'submit a memorial' form on Lincs to the Past Submit a memorial Please note, a * next to a box denotes that it needs to be completed in order for the form to be submitted. If you have any difficulties with the form, or have any questions about what to include that aren't answered in this guide please do contact the Lincolnshire Remembrance team on 01522 554959 or [email protected] Add a memorial to the map You can add a memorial to the map by clicking on it. Firstly you need to find its location by using the grab tool to move around the map, and the zoom in and out buttons. If you find that you have added it to the wrong area of the map you can move it by clicking again in the correct location. Memorial name * This information is needed to help us identify the memorial which is being recorded. Including a few words identifying what the memorial is, what it commemorates and a placename would be helpful. For example, 'Roll of Honour for the Men of Grasby WWI, All Saints church, Grasby'. Address * If a full address, including post code, is available, please enter it here. It should have a minimum of a street name: it needs to be enough information to help us identify approximately where a memorial is located, but you don’t need to include the full address. For example, you don’t need to tell us the County (as we know it will be Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire or North East Lincolnshire), and you don’t need to tell us the village, town or parish because they can be included in the boxes below. -

Summer 2012 Adults Supporting Adults [email protected] Issue 12

issue 12 Summer 2012 Adults Supporting Adults [email protected] Issue 12 would be greatly increased and therefore to retain a personal budget which represents this need is imperative. If one of your clients is approached for assessment please let the Sleaford office know as we will ensure a staff member is on hand to support the client through the process. We are currently working with the LCC FAB Team to ensure minimal disruption to our clients as possible through this procedure. New Services/Resources In the last year we have seen further developments of Spriteleys in Grantham and our Sitting and Shop2Gether projects, all of which are proving popular with clients and their families – we hope to expand these opportunities to more rural communities over the next year. If you think your village or community would benefit from such Hello to you all, I hope this support please contact me, you could be edition finds you well. helping to develop a new group close to your home for family and neighbours! There is so much going on in the Social Care Our volunteer project continues to develop Sector at the moment it’s hard to summarise and again we are always keen to meet into a few words! anyone who may be interested in offering a few hours a month of your time please I am sure you have heard or read in the contact Toni at our Sleaford office for more media Personalisation is changing the way details. services are being delivered - one of those changes being Personal Budgets. -

Division Arrangements for Grantham Barrowby

Hougham Honington Foston Ancaster Marston Barkston Long Bennington Syston Grantham North Sleaford Rural Allington Hough Belton & Manthorpe Great Gonerby Sedgebrook Londonthorpe & Harrowby Without Welby Grantham Barrowby Barrowby Grantham East Grantham West W Folkingham Rural o o l s t h o r Ropsley & Humby p e Grantham South B y B e l v o i r Old Somerby Harlaxton Denton Little Ponton & Stroxton Colsterworth Rural Boothby Pagnell Great Ponton County Division Parish 0 0.5 1 2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Grantham Barrowby © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Syston Grantham North Belton & Manthorpe Great Gonerby Hough Heydour Welby Barrowby Londonthorpe & Harrowby Without Braceby & Sapperton Grantham East Folkingham Rural Grantham West Grantham South Grantham Barrowby Ropsley & Humby Old Somerby Harlaxton Colsterworth Rural Little Ponton & Stroxton Boothby Pagnell County Division Parish 0 0.35 0.7 1.4 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Grantham East © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Claypole Stubton Leasingham Caythorpe North Rauceby Hough-on-the-Hill Normanton Westborough & Dry Doddington Sleaford Ruskington Sleaford Hougham Carlton Scroop South Rauceby Hough L o n g Ancaster B e n n i n Honington g t o Foston n Wilsford Silk Willoughby Marston Barkston Grantham North Syston Culverthorpe & Kelby Aswarby & Swarby Allington Sleaford Rural Belton & Manthorpe -

Anthony Bowen (Primary) Base: Base

Working Together Team Localities Autumn 2017 Rosie Veail (primary/secondary) Anthony Bowen (primary) Base: Base: Gainsborough Federation John Fielding School [email protected] [email protected] 07881 630195 07795 897884 PRIMARY PRIMARY BOSTON Blyton-cum-Laughton Boston West Corringham Butterwick Faldingworth Carlton Road Middle Rasen Fishtoft Benjamin Adlard Friskney Charles Baines Frithville Mercers Wood Gipsy Bridge Parish Church Pioneers St. George’s Hawthorn Tree Hillcrest Kirton Whites Wood Lane New York Grasby New Leake Hackthorn Old Leake Hemswell Cliff Park Castlewood Academy Sibsey Ingham St Marys Keelby St Nicholas Kelsey St Thomas Lea Francis Staniland Marton Stickney Morton Trentside Swineshead St Mary’s Osgodby Sutterton 4 Fields Tealby Tower Road Waddingham Wyberton Normanby-by-spital Wrangle Willoughton Newton-on-trent PRIMARY E&W LINDSEY Scampton Bardney Scampton Pollyplatt Billinghay Sturton-by-stow Binbrook Bucknall Coningsby St Michaels SECONDARY Horncastle Community Queen Elizabeth’s High School Kirby on Bain Trent Valley Academy Legsby Market Rasen Martin - MMK Mareham le Fen Scamblesby Tattershall – Primary Tattershall – Holy Trinity Tetford Theddlethorpe Walcott Woodhall Spa St Andrews Wragby Donington-on-bain South Hykeham Swinderby Thorpe-on-the-Hill Waddington all Saints Waddington Redwood Washingborough Welbourn Witham St Hugh’s Fiskerton Reepham Cherry Willingham Primary Nettleham Junior Nettelham Infants Scothern/Ellison Boulters Welton Nettleton Temporary Primary cover South Witham Cranwell Leasingham