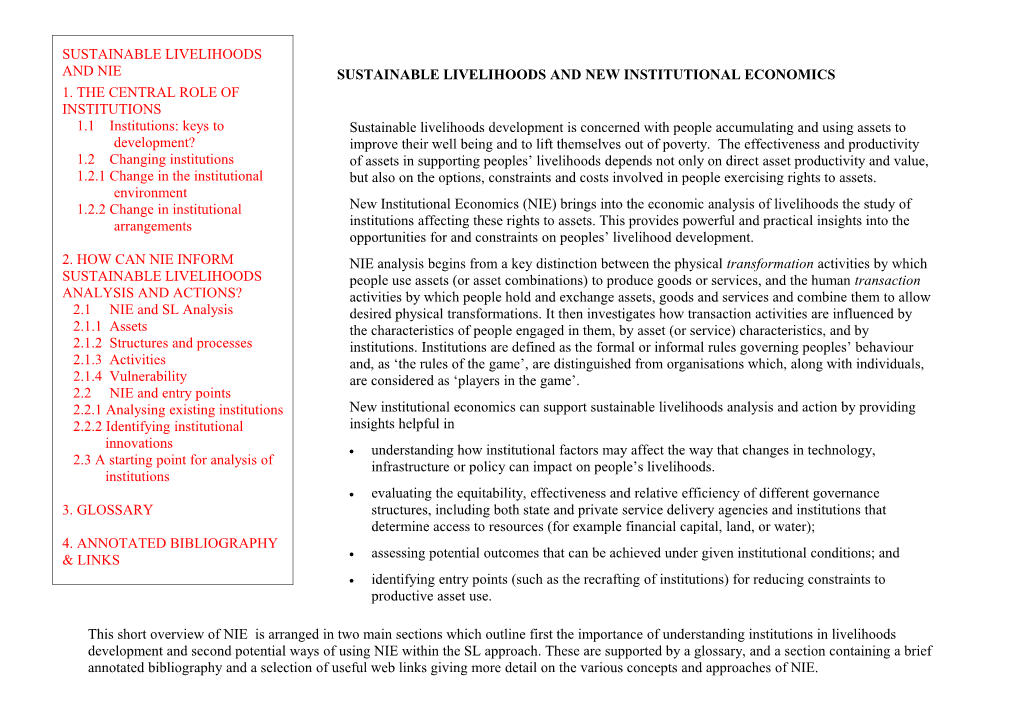

SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS AND NIE SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS AND NEW INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS 1. THE CENTRAL ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS 1.1 Institutions: keys to Sustainable livelihoods development is concerned with people accumulating and using assets to development? improve their well being and to lift themselves out of poverty. The effectiveness and productivity 1.2 Changing institutions of assets in supporting peoples’ livelihoods depends not only on direct asset productivity and value, 1.2.1 Change in the institutional but also on the options, constraints and costs involved in people exercising rights to assets. environment 1.2.2 Change in institutional New Institutional Economics (NIE) brings into the economic analysis of livelihoods the study of arrangements institutions affecting these rights to assets. This provides powerful and practical insights into the opportunities for and constraints on peoples’ livelihood development. 2. HOW CAN NIE INFORM NIE analysis begins from a key distinction between the physical transformation activities by which SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS people use assets (or asset combinations) to produce goods or services, and the human transaction ANALYSIS AND ACTIONS? activities by which people hold and exchange assets, goods and services and combine them to allow 2.1 NIE and SL Analysis desired physical transformations. It then investigates how transaction activities are influenced by 2.1.1 Assets the characteristics of people engaged in them, by asset (or service) characteristics, and by 2.1.2 Structures and processes institutions. Institutions are defined as the formal or informal rules governing peoples’ behaviour 2.1.3 Activities and, as ‘the rules of the game’, are distinguished from organisations which, along with individuals, 2.1.4 Vulnerability are considered as ‘players in the game’. 2.2 NIE and entry points 2.2.1 Analysing existing institutions New institutional economics can support sustainable livelihoods analysis and action by providing 2.2.2 Identifying institutional insights helpful in innovations understanding how institutional factors may affect the way that changes in technology, 2.3 A starting point for analysis of infrastructure or policy can impact on people’s livelihoods. institutions evaluating the equitability, effectiveness and relative efficiency of different governance 3. GLOSSARY structures, including both state and private service delivery agencies and institutions that determine access to resources (for example financial capital, land, or water); 4. ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY & LINKS assessing potential outcomes that can be achieved under given institutional conditions; and identifying entry points (such as the recrafting of institutions) for reducing constraints to productive asset use.

This short overview of NIE is arranged in two main sections which outline first the importance of understanding institutions in livelihoods development and second potential ways of using NIE within the SL approach. These are supported by a glossary, and a section containing a brief annotated bibliography and a selection of useful web links giving more detail on the various concepts and approaches of NIE. 1 THE CENTRAL ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS 1.1 Institutions: keys to development? A good starting point for understanding how institutions and transaction activities can affect development within a community is provided by the work of Douglass North1. North argues that wealth is created through trade (including all forms of exchange) since this allows different individuals, groups or regions to specialise in production activities according to comparative advantages in access to and use of assets. Trade, however, requires co-operation between the trading parties, and the transaction activities associated with this are costly. Aside from the physical costs of transport, buyers and sellers have to communicate to establish contact and then to bargain, agree and execute a transaction, with mechanisms to check and enforce the delivery and quality of goods, services and payments. The costs involved in communicating and enforcing transactions and the property rights on which they are based are known as transaction costs and these are incurred in order to reduce the risks of loss from transaction failure. If transaction costs and/or the risks of loss from transaction failure are too high, greater than the margin of revenues over physical transformation costs, then they will cancel out the cost savings and other benefits possible from trade. The result is market failure and trade will not then occur, with consequent loss of its wider benefits to society as a whole. Critical to our understanding of economic development, therefore, is an understanding of transaction costs and risks of transaction losses. Davis and North (1971) identify two major influences on transaction costs and on the risks of transaction failure: the institutional environment, and institutional arrangements. ‘Institutional arrangements’ are the forms of contract or arrangement that are set up for particular transactions (share cropping and commission sales are examples for land and commodity transactions respectively). The institutional environment (sometimes known as the institutional framework) is the broader set of institutions (or ‘rules of the game’) within which people and organisations develop and implement specific institutional arrangements. Formal institutions (such as by-laws, national laws, policies, the national constitution, and international laws and treaties) are clearly part of the institutional environment and distinct from institutional arrangements. The distinction may not always be so clear, however, for informal institutions (such as social customs and conventions) widespread acceptance of particular institutional arrangements as the norm can mean that in effect they become part of the institutional environment. North argues that in a close traditional village community, transaction costs between villagers are low: people know about each others’ activities and reliability while social relations and structures encourage people to keep agreements and also provide mechanisms for enforcing agreements

1 Link to bibliography and resolving disputes. For development to proceed, however, people need to trade between communities and with the wider national and international economies. This requires institutional environments and institutional arrangements that are effective in reducing the transaction costs and risks of increasingly complex and distant forms of trade and property rights. North argues that the development of the institutional environment is central to economic development, through its effects on transaction costs and risks, and hence on trade. Productive economic activity, with specialisation and complex forms of exchange, is thus stimulated in countries with a highly developed institutional environment. Countries with an under-developed institutional environment, on the other hand, have transaction costs and risks that are too high for actors to engage in complex forms of exchange, and they therefore remain relatively undifferentiated and cannot realise gains to be made from specialisation and economies of scale. North concludes that "the inability of societies to develop effective, low-cost enforcement of contracts is the most important source of both historical stagnation and contemporary underdevelopment in the Third World." Our summary of NIE analysis provides three entry points to reduce transaction costs and risks: development of the institutional environment, development of more effective institutional arrangements within the existing institutional environment, and development of infrastructure and services to improve communication and reduce its costs. These are very relevant to sustainable livelihoods analysis, and to household, meso, macro and international scales of analysis. (See Box 1) We conclude this section by noting that fundamentally NIE involves a recognition that holistic analysis of economic activity requires explicit reference to institutions. It is also recognised, however, that institutions exist for a wide variety of reasons, and in analysing them and their development, their varied and often multiple roles will not be understood by economic analysis alone.

BOX 1 – Reducing the transaction costs associated with input provision by the private sector Consider the participation of the commercial private sector in the provision of services. North’s ideas focus attention on the transaction costs and risks faced by firms in providing services and by entrepreneurs in using those services in productive activities. These may be reduced by improvements in: The institutional environment: e.g. ensuring secure property rights to promote private sector investment in transport and storage facilities, improved market information, regulation of weights and measures, clear product quality standards, stable macro-economic policies (to control inflation and preserve the value of investments) Institutional arrangements: e.g. promoting enterprise groups, facilitating provider/user links Infrastructure: providing roads to reduce transport costs for products and for people, investing in telephone systems to facilitate the transfer of information

1.2 Changing Institutions Identification of the critical role of institutions in development leads to questions about how institutions are formed and their effects on different groups in society, particularly the poor and disadvantaged. Examination of both historical and contemporary development shows that in some societies institutions have at times changed in ways that broadly reduce transaction costs and risks, thus promoting production, trade and development, but at other times and in other societies institutions have suppressed these activities by increasing transaction costs. We therefore need to understand how institutions form and change, and why they may evolve along different paths. Institutional change involves gains or losses for society as a whole and for different groups within society, but change itself is likely to be driven more by the interests of powerful groups with the greatest influence over those institutions. When evaluating institutional change, therefore, a delicate but important analytical task is to judge the overall efficiency gains from improved co-ordination under particular institutions and the benefits and risks for poor or disadvantaged groups against the potential for exploitation by vested interests.

Case Study 1: Sharecropping in Sindh Province Pakistan: Feudal Tyranny or “Social Security System”?

1.2.1 Change in the institutional environment For the institutional environment, path dependency and power are recognised as two critical influences on institutional change. Institutions normally evolve, and thus institutions are often formed by incremental change of earlier institutions. Formal institutions are often more amenable to reform and radical change (through revolution, presidential edict, government policy changes or new laws, for example) but informal institutions, often deeply embedded in culture, adjust more slowly and may pull in opposite directions to (and undermine) changes in formal institutions. North holds that it is the powerful groups in society who determine the institutional environment, particularly the formal rules. This they do primarily for their own private interests, according to their historical and cultural setting and to their subjective (and ideological) understanding of how the world works. If the powerful groups in society perceive it to be in their interests to develop institutions that encourage trade, then the weaker members of society also prosper. If institutions that are put in place discourage trade, however, the poor suffer. Thus if a country’s elite perceive that they will increase their welfare by supporting institutions that encourage trade while taking only a small share of its benefits, this is likely to promote development. If, however, they concentrate on capturing large shares of the benefits of trade (for example through legal or illegal taxes), or try to retain or increase control over particular patterns of economic activity, then this will increase transaction costs and risks and depress development. Understanding institutional change is therefore not a simple question of economics but involves political economy, social anthropology and stakeholder analysis as well as the analysis of market failures in the development of different institutional frameworks. 1.2.2 Change in institutional arrangements Similar considerations of path dependence, power and the wider environment influence the formation of institutional arrangements, but these are also influenced by the nature of the particular assets or transactions with which they are concerned. It is helpful to consider two related functions of institutional arrangements, to support asset exchange between transacting parties, and to support asset coordination amongst those holding, buying or selling similar assets. In asset exchange, we may identify three broad forms of institutional arrangement between transacting parties. Spot transactions (the impersonal free market ideal) are one extreme form of contract, contrasting with non-market transactions, which are embedded within personalised, long term social or organisational relations without any market exchange (clan relations and commercial firms are both examples of this form of arrangement). Intermediate forms of contract might involve longer term or non-standard forms of market contract which involve both market and personal relationships (long term supplier relations or share cropping, for example). Asset coordination is beneficial where people obtain relatively small individual gains from holding, buying or selling assets (due to low unit value or to small scales of activity), and the associated transaction costs have a high fixed cost element which is incurred irrespective of the scale of the holding or transaction. Considerable savings can then be made in the costs of holding or exchanging an asset if the scale of holding or exchange can be increased through coordination or consolidation. This might apply, for example, for forest dwellers resisting encroachment by a logging company, for small scale irrigators allocating water between themselves, or for small scale urban entrepreneurs buying inputs or selling finished products. Coordination may be achieved through private, state or collective arrangements which in turn consolidate asset holding (or buying or selling) at three levels: management, use and ownership. Thus forest dwellers might adopt collective management arrangements to work together to defend their forest, a state irrigation department (with state ownership of water resources) might allocate water rights to small scale irrigators, and small scale urban entrepreneurs might set up a co-operative or use the services of private market agencies to sell their products on commission (involving collective or private coordination of asset use). Actors’ preferences for different contractual arrangements depend upon the benefits, transformation costs, transaction costs and risks associated with each set of arrangements. Analysis of these costs enables understanding of the relative performance of different institutional arrangements under different conditions. Thus well defined property rights (with a well developed institutional environment and appropriate asset characteristics) tend to disproportionately decrease parties’ transaction costs for market based and private arrangements. Transaction risks, however, tend to increase with such arrangements (as the parties have less access to and information about each other), and the importance of risk to contracting parties varies with risk aversion (often related to poverty and to livelihood or income diversity), the extent to which investments or their benefits will be lost if the transaction fails (known as asset specificity and often affected by technology, for example investment in specialist equipment or buildings), and the scope for opportunistic behaviour by other parties to renege on agreements.

Scope for opportunistic behaviour depends upon the institutional environment, power relations of the different parties, and the characteristics of the asset concerned. Particular difficulties arise where resources are mobile, not easily differentiated (according to owner), and dispersed (common characteristics of ‘common property’ natural resources) or where quality is variable and difficult to monitor. Institutional arrangements are often crafted to constrain opportunistic behaviour. Collective institutions and non-market and intermediate forms of contract, for example, tend to rely upon expected future gains from repeated relations between parties as incentives to fulfil agreements, with transaction costs and risks and scope for opportunism reduced by building up personal relations, knowledge, and longer term co-operation. An important conclusion from this analysis is that if a set of actors face major transaction risks, then institutional arrangements that are apparently non-competitive and/or inequitable may be more efficient than and preferred (by all parties) to competitive market arrangements. There may then be a role for the state and for development agents to support institutional innovation and the development of conditions that promote such institutional arrangements. (See Box 2)

BOX 2: The choice of institutional arrangements In asset exchange: Spot transactions may be preferred by parties with low vulnerability and risk aversion operating in a well developed institutional environment that reduces scope for opportunistic behaviour by other parties. Non-market transactions and intermediate forms of contract will tend to be preferred by parties who are concerned about the risk of transaction failure. This arises from risk aversion (due to vulnerability or high investment in specific assets, for example), with proneness to opportunistic behaviour by other parties due to a weak institutional environment, weak power relations, or difficulties in enforcing transaction due to asset characteristics such as hidden quality variations. In asset coordination: Private arrangements tend to operate best where there are well functioning labour and capital markets. Collective institutions may provide coordination at a lower cost when it is very costly or impossible to allocate exclusively to one individual an appropriate share of the benefits deriving from a resource, but it is possible to allocate those benefits exclusively to a clearly defined group of individuals; or the group engaged in collective action includes all or most of those individuals who commonly enjoy property rights over the resource; or the group engaged in collective action is sufficiently small and/or homogeneous to permit effective co-ordination. These conditions depend upon the institutional environment and asset characteristics. The chances of effective collective action are improved if the resource is fixed and immobile and property rights over it are fairly localised (e.g. Forestry); if any mobility is confined within a relatively small area with clear boundaries (e.g. irrigation systems or fish in a small body of water); or if external effects of resource usage are fairly localised and do not impact negatively upon groups of individuals outside the collective action Where resources do not have these characteristics then collective action may become harder since with less localised property rights and externalities, collective resource management involves an increasing number of participants and rapidly rising co-ordination costs. As these rise towards an untenable level it may become necessary for the State to become involved in the regulation of resource use. Institutional arrangements evolve, however, to match not only the interests of the different contracting parties’ but also their relative power, considered in terms of market power (the gains parties can achieve from alternative uses of their resources, outside the transaction) and non- market power (social, legal or illegal pressures or threats that each party may use to influence the other). As the poor often engage in transactions from a position of relative weakness, then a shift in power relations (through an expansion in their market power with the development of alternative asset uses, or through a change in non-market relations) may offer scope for changing contractual arrangements to their advantage. However, if changes merely restrict the market or non-market power of the entrepreneurs with whom the poor transact (for example traders, money lenders, employers or landowners), care must be taken that it does not weaken these entrepreneurs’ gains to the extent that they withdraw from these transactions altogether, reducing the livelihood options for the poor. 2 NEW INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS DEVELOPMENT How can New Institutional Economics help in sustainable livelihoods development, in analysis and action? We consider first how NIE analysis can help in developing an understanding of particular livelihoods, and then how it can be used to identify potential ‘entry points’ for outside intervention. A major potential contribution for NIE is to promote a more nuanced application of economic analysis in livelihood analysis, providing a common link in understanding for economists and for other social scientists sceptical of traditional economics’ sometimes naïve emphasis on markets. For natural scientists, NIE can provide a more holistic context in which to understand technological development and adoption.

2.1 NIE and Livelihoods Analysis An understanding of NIE can help livelihoods analysis in two ways: by drawing attention to important livelihood components and to useful questions to ask, and by drawing attention to particular ways that institutions affect the relationships between livelihood components – both within the micro scale of analysis, and within and linking meso and macro scales of analysis. We now consider the application of such NIE insights to each of the major livelihoods components.

2.1.1 NIE and policies, institutions and processes An important insight arising from NIE is the relationship between the institutional environment, institutional arrangements, and peoples’ activities. NIE provides an analytical framework for examining the importance and effects of policies, institutions, and processes that make up the formal and informal institutional environment, from international and national institutions to those, such as gender relations, operating within communities and households. This gives insights into the pressures for, constraints on and possible effects of institutional change (on resource access, utilisation and productivity; on opportunities for and constraints on trade based activities; and on livelihood outcomes for different people). More specifically, NIE provides a framework for examining the institutional interactions between assets, activities, and outcomes; for analysing the effects of power and the processes of (and incentives for) institutional and livelihood change; and for understanding the reasons for and effects of different institutional arrangements. 2.1.2 NIE and assets NIE analysis links in well with the SL emphasis on assets in a number of ways. First, it emphasises that institutions (the institutional environment and arrangements) are a very important part of social capital. Whereas the institutional environment is an asset that tends to be held more at larger scales of analysis (community, national, or international, for example), access to particular institutional arrangements is an important part of individuals’ social capital, together with a culture of trust between transacting or co-operating parties The institutional arrangements that people are able to engage in also depend upon and affect their relative power (individually or collectively) and determine their access to and gains from other assets. Second, NIE emphasises and gives insights into the importance of access to assets. Access to assets, and consequently benefits from them and incentives for their development, depend upon institutional arrangements, and these in turn depend upon the institutional environment, information flows, asset characteristics, and the vulnerability and power of different actors. The physical and economic characteristics of assets should not be examined without reference to the institutional arrangements which constrain or promote their use. A third insight from NIE concerns the importance of information as a resource. This has implications for the valuation of human and physical capital. Effective information flow and use are important pre-requisites for the development of the institutional environment, and this may require investment in literacy, in communications infrastructure, or in a culture of openness and information sharing. Finally, NIE analysis can make an important contribution to understanding the value of physical and natural assets. Market valuations are inadequate as they do not take account of transaction costs and risks as well as transformation costs involved in asset use or production. This goes beyond the simple recognition that, for example, the value of soil conservation is reduced by uncertainty about land tenure, to identify the situations where different types of institutional arrangement may reduce transaction costs and risks, and increase asset values to different users. Thus users of a watershed may not cooperate to maximise benefits from watershed use if they have insufficient knowledge about each other, but collective arrangements facilitating better information about each others’ behaviour and trustworthiness may help to overcome this problem. If, however, the transactions costs of upholding exclusive property rights over a resource are greater than the potential benefits, whatever institutional arrangements are adopted, then ‘open access’ will prevail, with devaluation and often degradation of assets.

2.1.3 NIE and livelihood activities We identify two principle thrusts of NIE’s contribution to understanding of livelihood activities. First, given the importance of institutional arrangements, the development and maintenance of these arrangements becomes a critical livelihood activity. Productive and equitable arrangements are not only an important part of social capital as a livelihood base, but also a livelihood outcome in themselves, enhancing dignity and freedom. Poor people demonstrate this by investing resources in such activities, and such investment should be understood, valued and supported. Second, NIE provides a framework for exploring relationships between technological change for productive activities and institutions that different technologies require. Increased productivity is commonly achieved by product and process specialisation, with greater numbers of linkages between actors producing and consuming different goods and services or involved in different stages of production. Such linkages, however, carry transaction costs and risks, and require low cost institutional arrangements. There are several obvious, but easily forgotten, implications of this. First, much technological change relies on institutions if it is to be practical and realise its potential benefits. At its simplest, increased productivity often needs product markets, but there are often also needs for input markets, for credit and savings facilities, and for investments in specific assets. Where the institutional environment is weakly developed (with weak laws or enforcement, high crime rates, corruption, poor macro-economic management, etc.), where communications are poor, or where people are risk averse due to poverty and vulnerability, then the scope for more productive technology is severely limited. Under such circumstances attention needs to be focussed on technologies which are institutionally ‘appropriate’ and make much more limited institutional demands, on the development of communications and of the institutional environment, on reducing peoples’ vulnerability and risk aversion (without reducing the incentives for success), and on the development of non-market, intermediate, collective or state arrangements to support essential transactions.

Case Study 2 - Agricultural Commercialisation, Specialisation and Transaction Costs

2.1.4 NIE and vulnerability Institutions are both a source of vulnerability and are affected by it. Thus a weak institutional environment promotes vulnerability in the definition of property rights and in exchange. An important influence on the development of institutional arrangements is the way that they may reduce risk and vulnerability, but risk reduction may be achieved at a cost of overall productivity, and the more vulnerable that people are (in terms of the exposure to, and livelihood impacts of, a range of adverse events), then the more likely they are to choose low risk institutional arrangements at the cost of lower average productivity. Link back to Case Study 1 Such arrangements may involve exploitative patron-client relations with some form of social safety net, or adverse but guaranteed markets for inputs or products. Understanding institutional arrangements for access to key assets will often be critical for understanding peoples’ vulnerability. 2.2 Identifying entry points Given the centrality of institutions to the development process, NIE identifies a number of potential entry points for interventions designed to improve livelihood options. It can help us to answer a range of questions such as How are transaction costs likely to affect the net benefit calculation of a given intervention? What are the most efficient institutional arrangements for achieving a given contractual outcome? Where can viable modifications in the institutional environment serve to reduce transaction costs and improve access, productivity and equity? Is it feasible to aim for ‘participatory’ solutions, given the institutional environment, power relations and the transaction costs that are likely to prevail? We illustrate this with examples focussing on the potential role for NIE first in the analysis of existing institutions and then in the evaluation of innovations in institutional arrangements. 2.2.1 Analysing existing institutions: are they enabling or disabling? Institutions can facilitate or hinder the generation of wealth. Livelihoods analysis should therefore screen existing institutions for their effectiveness. Only when this analysis has taken place should analysts investigate the possibilities for institutional innovations aimed at improving livelihood outcomes. Institutions form for a variety of reasons (see section 1.2). The reason for the formation of a particular institution, whilst it may appear to have negative distributional impacts, may actually enable poor people to increase their livelihood options. A striking example is given in Case study 3. This shows how a seemingly highly extractive institution may in fact be relatively efficient, given the prevailing institutional environment. In analysing the effectiveness of an institution it is therefore crucial to understand the costs and benefits associated with its existence before comparing it with alternative arrangements and considering how it may be reformed to improve the potential livelihood options of the poor. Case Study 3 - Farmer and consumer benefits from trader monopolies?

We also need to recognise that commonly held beliefs about appropriate institutions are increasingly challenged by the existence of external influences. Case study 4 indicates that the outcomes associated with a set of institutions must not be taken for granted, as they are, themselves, a central component of the analysis. Case Study 4 - Is small scale agriculture efficient?

2.2.2 Identifying institutional innovations Where an analysis of existing institutions determines that they are not functioning as well as they might, then it is appropriate to look for institutional innovations that can reduce transaction costs and risks. This may be achieved by changing arrangements for and costs in screening and monitoring resources or other parties, by strengthening property right enforcement, by improving information systems, or by encouraging economies of scale through consolidated management, use or ownership under private, state or collective arrangements. In seeking institutional innovations, one needs to bear in mind that: Such modifications need to be considered in the light of particular asset characteristics and of existing bundles of formal and informal institutions, which will differ, often substantially, between communities.

Institutional innovation can be aimed at macro and/or micro levels of decision making. Case study 5 illustrates a number of potential advantages and pitfalls of decentralisation of government activities.

Case Study 5 - When is decentralisation appropriate?

The characteristics of the assets and the institutional environment within which livelihood strategies are functioning are central and reflection on these aspects can assist greatly in determining appropriate entry points and innovations. Financial markets, for example, face particular institutional difficulties associated with the characteristics of financial services.

Case Study 6 - Coping With Credit Market Failure

When an institutional innovation is pursued, it is crucial that the interests of powerful groups are taken into account and that there are incentives and/or mechanisms to promote their support for any change. 2.3 Applying NIE: A starting point for analysis of institutions It can be difficult to determine the most appropriate approach for analysing institutions since there is a wide variety of transaction activities that are amenable to analysis by NIE. A useful starting point in the analysis of existing institutions is to consider the characteristics of the assets that are affected by the institution(s) in question. For assets conducive to private ownership because markets can (potentially) function efficiently (for example, inputs such as credit or raw materials), one might begin by investigating the competitiveness of the markets in which these inputs are sourced in order to develop an understanding of the form and effectiveness of current contractual arrangements. This is illustrated in case study 1 and case study 3.0

Link back to Case Studies 1 and 3

For goods where markets are unlikely to exist (where private property rights are too costly to define and enforce), one might investigate the appropriateness of collective arrangements such as common property regimes, with analysis of how well current institutions are supporting collective action. In such cases, analysis is concerned not simply with transactions by the group controlling access and use of the resource, but also with the make up of the group itself and its interaction with the characteristics of the range of assets they are managing.

Link to: Multiple Uses of Common Pool Resources in Semi-Arid West Africa: A Survey of Existing Practices and Options for Sustainable Resource Management. Timothy O. Williams (1998) http://www.oneworld.org/odi/nrp/38.html 3. GLOSSARY Asset specificity is where a productive asset is largely limited to one specific use. Where investments in such assets are non-trivial, considerable effort will be made to arrange transactions that will provide continuity in the use of the asset. Without continuity it may not be possible to achieve a positive return on the investment. Fishing technology, for example, requires significant investments, and once these have been made these assets cannot easily be transferred to other uses. The owners of such technology will therefore seek contracts that will guarantee them access to a level of fisheries resources that will at least enable them to cover their investment costs. The negotiation and enforcement of such contracts raises the level of transaction costs. Many investments aimed at improved natural management involve expenditure on assets that cannot easily be transferred to other uses. Examples include water conservation technologies, such as canal lining, reservoirs, irrigation control gates, and drainage; soil conservation technologies, such as terracing and walls; some of the investment in human capital and environmental management skills. Appropriate institutional mechanisms are required in order to ensure an adequate ‘return’ on such assets. Without such institutions the ‘returns’ will not warrant the initial investment and investment incentives will be minimal. Asymmetric information occurs where access to information by one party (or parties) to a transaction is better than access by another party. Asymmetric information can be used as a source of power in determining the outcome of the transaction. . A common example is where the seller of a good knows much more about the characteristics of that good than the buyer (see also Imperfect Information) Bounded rationality is the condition in which decision making is motivated by the desire to maximise economic benefits, whilst being limited by imperfect information. It is a condition in which individuals are intendedly rational, but are subject to limited cognitive competence as a result of imperfect information. Common pool resources (CPR) are characterised by the difficulty of excluding actors from using them and the fact that the use by one individual or group means that less is available for use by others. (The latter point distinguishes CPR from pure public goods which exhibit both non excludability and non rivalry in consumption). CPRs include some fisheries, irrigation systems and grazing areas. Common Property Rights Regime refers to a particular definition of property rights over a resource or asset where ownership is by an identified group, rather than an individual. Such regimes are often the most appropriate for ensuring optimal use of Common Pool resources. Externalities exist where the activities of those actors party to a transaction affect (either positively or negatively) a third party and no account is made of that effect in terms of payment or compensation. Externalities are an example of market failure due to a weak definition of property rights over an asset. Fixed costs (of transaction) refer to any costs that do not vary in proportion with the scale of an economic activity and are thus higher per unit transacted for smaller scales of activity. Imperfect information. In a world in which information is imperfect, the cost of obtaining information is positive, and where resources are scarce, the measurement, monitoring and enforcement of contracts are unlikely to be perfect. So long as information is not perfect, economic agents engaged in transactions will have to submit to a certain amount of uncertainty. Uncertainty can be reduced by devoting more time and resources to measuring, monitoring and enforcement, and, in general, the greater the perceived uncertainty, the more resources will have to be devoted to these activities if transactions are to take place. Where these activities are unable to reduce uncertainty sufficiently, or where the cost of doing so is too high, new, innovative institutions for and ways of conducting measurement, monitoring and enforcement and reducing their associated transaction costs will have to be found. Otherwise transactions will not occur. Institutions are defined as the formal or informal rules governing peoples’ and organisations’ behaviour. Institutions, ‘the rules of the game’, are distinguished from organisations which, along with individuals, are considered as ‘players in the game’. Formal institutions (such as by-laws, national laws, policies, the national constitution, and international laws and treaties) are part of the institutional environment and distinct from institutional arrangements. For informal institutions (such as social customs and conventions), the distinction may not always be so clear. However, widespread acceptance of particular institutional arrangements as the norm can mean that in effect they become part of the institutional environment. Institutional arrangements are defined as the forms of contract or arrangement that are set up for particular transactions or holding of assets. Institutional environment is defined as the broader set of institutions (or ‘rules of the game’) within which people and organisations develop and implement specific institutional arrangements Non-market transaction refers to an exchange of rights over the ownership and/or use of an asset or good that does not involve a market exchange. Opportunism is ‘a condition of self-interest seeking with guile’ which is permitted by asymmetric information whereby one party to a contract has information that the other party does not. It too arises as a consequence of imperfect information. Opportunistic behaviour, occurs where one party to a contract takes advantage of his superior knowledge, in order to further his interests, by failing to disclose such information to the other contracting party. This would occur, for example, if a supplier of pesticide had information about a product which was deliberately withheld from the potential buyer, in the knowledge that such information would negatively affect the price of the product or the willingness of the buyer to purchase it. This type of opportunistic behaviour causes what is known in the NIE literature as adverse selection, and generally takes place ex- ante the contract as a result of imperfect measurement. Opportunism can also occur ex-post, when one party, the principal, to the contract is unable to monitor and enforce the performance in meeting contracted obligations of the other party, the agent. This is sometimes known as moral hazard or the principal-agent problem, and reduces the incentive for agents to fulfil their contractual obligations, thereby leading to shirking or free riding Path dependence refers to the institutions at one place in time being determined by their evolution from earlier institutions. It is defined by North as “a term used to account for the parallel characteristic of an institutional framework that has shaped downstream institutional choices and in consequence makes it difficult to alter the direction of an economy once it is on a particular institutional path. The reason is that the organizations of an economy and the interest groups they produce are a consequence of the opportunity set provided by the existing institutional framework. The resulting complementarities, economies of scope and network externalities reflect the symbiotic interdependence among the existing rules, the complementary informal constraints, and the interests of members of organizations created as a consequence of the institutional framework. In effect, an institutional matrix creates organizations and interest groups whose welfare depends on that institutional framework”. Definition taken from North, D (1997) The Contribution of the New Institutional Economics to an Understanding of the Transition Problem. 1997 UNU/WIDER Annual Lecture http://www.wider.unu.edu/northpl.htm Property rights are the legally defined and enforceable rights which relate to ownership and use of resources. (See article in Bibliography for further detail) Risk aversion describes a situation where actors are either unwilling to engage in a transaction for fear that it will fail, leaving them with some form of financial loss, or adopt institutional arrangements with high transaction costs to reduce the probability of such a loss, even though the extra costs incurred in avoiding the loss are greater than the average benefits expected from avoiding the loss. Transaction refers to the activities that allow/constrain transformation activities. A transaction occurs when two or more parties enter into a contract in which rights and obligations are exchanged. Transactions range from those where all the rights and obligations under the contract take place at a single instant in time, with no rights or obligations remaining outstanding after the instant in time has passed (this is the purest form of spot market transaction) to those which involve a continuous exchange in which reciprocal rights and obligations are part of a permanent contractual arrangement, with no specific termination point such as in the case of the long-term relationship between landlords and tenants, between plantation owners and their permanent employees, or between a fisheries management authority and individual fishermen. Transactions also include those activities required to define, implement and enforce a given set of property rights over an asset. Transaction costs are the costs associated with the transactions that are necessary for transformation activity to occur. These costs can be usefully divided into ex-ante costs and ex-post costs. Ex-ante costs involve the costs associated with gathering information about an asset or the good or service derived from its use, and about the other parties involved and the negotiating of and devising a contract or set of rights in such a way as to maximise the likelihood of the contracting partners meeting their obligations under the contract. Measurement costs are an important part of the ex-ante cost of a transaction. These are the costs involved in gathering information about the attribute of a commodity or service that is to be the object of a contract and about the reliability and trustworthiness of other parties to the contract. A fisheries management authority needs to obtain information about the state of the natural resource base, as well as about fishermen, before it enters into a contract with fishermen entailing the allocation of fishing rights and the provision of management services in exchange for the undertaking by fishermen to abide by certain rules and regulations. Without such information the objectives of fisheries management are unlikely to be realised. Ex-post costs are those associated with monitoring the performance of any contract or set of property rights associated with the use or exchange, to ensure that the contracting partner is meeting his/her obligations that are incurred once a contract has been negotiated and agreed, and where a transaction is extended over time, and enforcing contracts where the contracting partner fails to meet the obligations stipulated in the agreement. Enforcement costs are incurred when a party to a contract strays from the obligations laid down in the agreement, and are associated with measures taken by the aggrieved party to rectify matters. The exclusion of parties from using resources where ownership is defined to others is another example of an ex-post cost. Transformation in the context of NIE refers to the physical process by which inputs are converted into outputs. For example, a production technology utilises labour, in combination with other resources, to produce rice. 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND LINKS

This section provides a selection of potential sources of follow up material. The sources include seminal texts, articles and websites.

The central role of institutions North, D. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press. North develops an analytical framework for understanding the role of institutions in economic development and for elaborating a theory of institutional change. The text provides a concise definition of institutions and explains their distinction from organisations. The author demonstrates that institutions, and the way in which they change, affect the performance of economies, by explaining the manner in which institutions create the incentive structure within an economy. Eggertsson, T. (1990). Economic Behavior and Institutions. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. A survey of institutional analysis within various branches of economics, this book gives a strong, whilst readily accessible, theoretical account of New Institutional Economics. A particular strength is its focus on the relationships between property rights and transaction costs, as they affect economic organisation. Nabli, M. K. and J. B. Nugent (1989). “The New Institutional Economics and its Applicability to Development.” World Development 17(9): 1333-1347. This paper serves two important purposes: (a) it clearly identifies the interrelationships between what are sometimes considered to be diverse strands of analysis within the NIE, and (b) illustrates how the concepts might be used to approach the analysis of development. The authors suggest that “LDC governments can change the nature of transaction costs and information costs, either reducing their importance or magnifying them and thereby creating additional sources of opportunistic behavior”

The International Society for New Institutional Economics (ISNIE) http://www.isnie.org This website provides information on forthcoming ISNIE conferences and holds online papers on a wide range of NIE related topics

From Neo-classical Economics to New Institutional Economics (PDF file1) The brief extract demonstrates that an extremely valuable attribute of NIE is that it rests on a firm conceptual and theoretical basis, thus allowing for rigorous analysis of the efficiency of resource use. NIE shares with neo-classical economics the assumptions of rational, maximising, self-interested, economic agents. However, it relaxes some of the more restrictive assumptions of neo-classical perfect competition to reflect more common, real world situations. Changing Institutions A useful distinction for those wishing to access the wider literature, can be made between the Transaction Costs school which focuses on contractual arrangements for asset exchange in private transactions and the Property Rights school where the interest is on the contractual arrangements for co-ordinating access and control of assets which may or may not be held in private ownership.

Williamson, O. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York, Free Press. This book explains in detail, the basic constructs of transaction cost economics, and demonstrates how it can be applied to the study of economic organisations. The text covers such topics as the determination and governance of contractual arrangements, vertical integration and asset specificity.

Workshop in Political Theory And Policy Analysis, Indiana University http://www.indiana.edu/~workshop Elinor Ostrom and associates at the Workshop have played a central role in the understanding of how the design of an institution motivates actors who provide, access and/or use common pool resources. The workshop has developed a large on-line bibliographical database on Institutional analysis http://www.indiana.edu/~workshop/wsl/wsl.html Particularly useful papers/texts developed at the Workshop include: Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York, Cambridge University Press. Ostrom, E. and R. Gardner (1993). “Coping with Asymmetries in the Commons - Self Governing irrigation Systems can Work.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7(4): 93-112. Ostrom, E., L. Schroeder, et al. (1993). Institutional Incentives and Sustainable Development: Infrastructure Policies in Perspective. Boulder, Westview Press.

International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP) on http://www.indiana.edu/~iascp/articles.html

UNU/WIDER Research and Training Programme Studies of Institutional and Distributive Issues http://www.wider.unu.edu/pro9899c2.htm Provides information and papers on a research theme which draws upon the NIE in the context of development. A recent paper provides a useful review of the issues involved in the group access/use of resources, as informed by NIE : Group Behaviour and Development by Judith Heyer, Frances Stewart and Rosemary Thorp, June 1999. http://www.wider.unu.edu/wp161.pdf Property Rights Revisited (PDF file 2) This excerpt from the Wye College External Programme course: Natural Resource Economics (Unit 10 Section 1) examines the relationship between property rights regimes and transaction cost economics. Particular attention is paid to how the type of property rights regime and the distribution of these rights between interested parties affect the outcome of transactions in the natural resource sector.

Bromley, D. (1991). PROPERTY RIGHT PROBLEMS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN Chapter 7 pages 137- 145 In: Environment and Economy: Property rights and Public Policy. Oxford, Basil Blackwell. In this chapter Bromley demonstrates that establishing private property rights over some resources (e.g. rangeland, forests etc) is often difficult if not impossible, and that a system of property rights involving state or communal ownership may be less costly to implement by developing a simple model to demonstrate the relationship between the property right regime and the cost of implementing that regime. A useful elaboration of the role of property rights is also provided by the author at http://www.idrc.org.sg/eepsea/publications/spaper/Bromley.htm

New Institutional Economics and Sustainable Livelihoods Development A number of illustrative examples of research initiatives applying the insights of NIE in the context of livelihoods development are given below: Common pool resources Multiple uses of common pool resources in semi-arid West Africa: A survey of existing practices and options for sustainable resource management November 1998, Timothy O. Williams http://www.oneworld.org/odi/nrp/38.html

Land tenure The Land Tenure section of Sustainable Development Dimensions, a service of the Sustainable Development Department (SD) of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) http://www.fao.org/WAICENT/FAOINFO/SUSTDEV/LTdirect/default.htm contains information on land tenure issues.

Similarly, see the Land Tenure Center at Wisconsin University– Maddison http://www.wisc.edu/ltc/ Input marketing Dorward, A., J. Kydd and C. Poulton (eds.) (1998) Smallholder Cash Crop Production Under Market Liberalisation: A New Institutional Economics Perspective. CAB International. This book examines some of the challenges facing smallholder cash crop production in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia under current policies of market liberalisation. It looks not just at activity in the crop output market, but also at the performance of liberalised markets for seasonal inputs and, in particular, at linkages between the input and output markets, drawing on case studies from Ghana, Tanzania and Pakistan. The book is informed by a New Institutional Economics perspective, which focuses attention, inter alia, on problems of market failure and the incentives for economic agents to devise “institutional” responses to these problems. It highlights the importance of informal, as well as formal, institutional development in the establishment of an efficient market economy. At points the book considers the role that aid donors and NGOs can play in specific situations. However, its major concern is with the capacity of the (emerging) private sector to tackle the problems inherent in providing services in liberalised rural markets. This is combined with a frank assessment of the capacity of the state in many Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asian nations to “correct” for failures in liberalised markets and to pursue effectively any wider equity and environmental objectives

Commercial financing of seasonal input use by smallholders in liberalised agricultural marketing systems Number 30, April 1998, Andrew Dorward, Jonathan Kydd, Fergus Lyon, Nigel Poole, Colin Poulton, Laurence Smith and Michael Stockbridge http://www.oneworld.org/odi/nrp/30.html This briefing paper provides summary information on the application of NIE to input marketing

The ADU, Wye College website http://www.wye.ac.uk/INLOCK/index.html This site contains information on a DFID funded research project “Interlocking Transactions: Market Alternatives for Renewable Natural Resource (RNR) Services”