APPENDIX B: SUGGESTIONS FOR CONSTRUCTING MULTIPLE-CHOICE ITEMS From Linn/Miller, Measurement and Assessment in Teaching, 9e

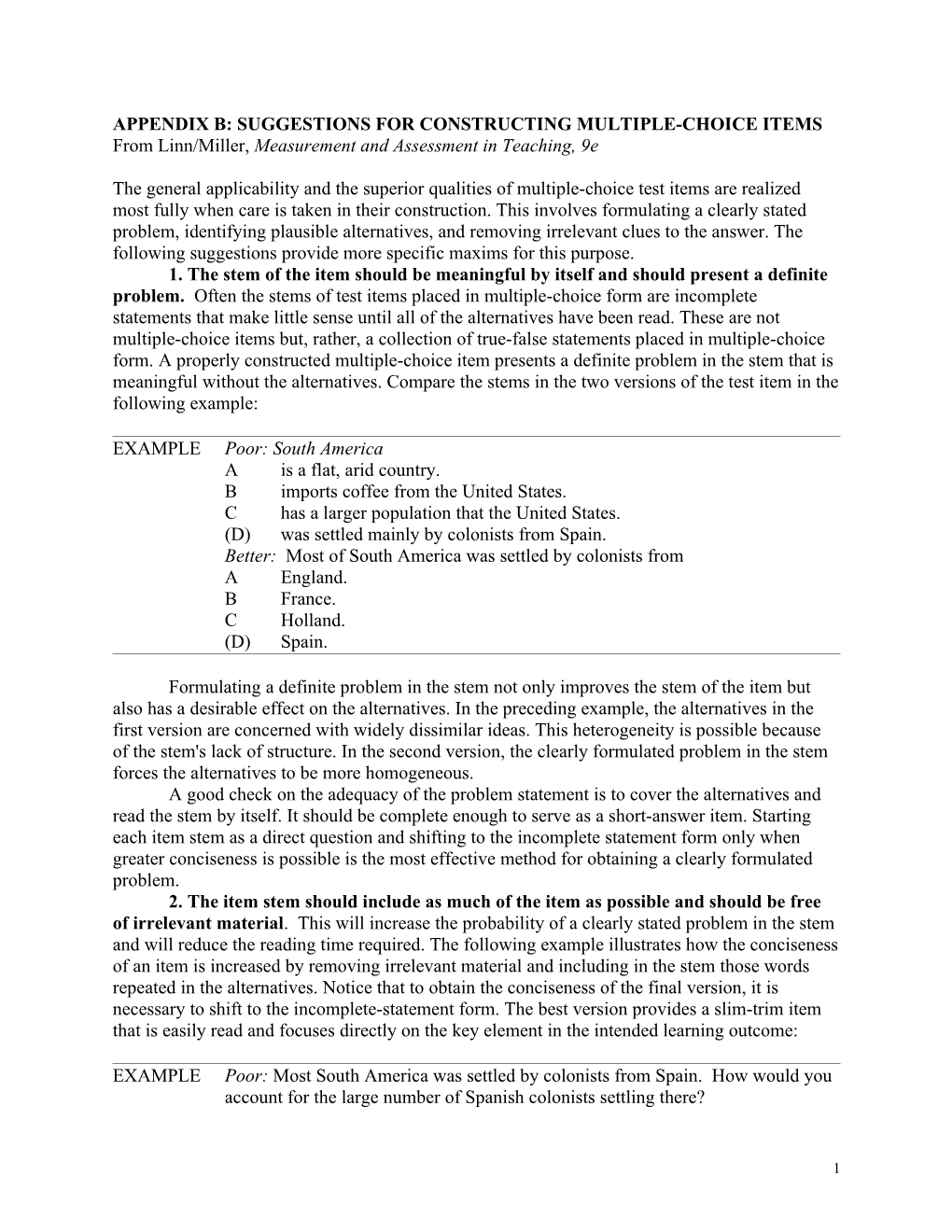

The general applicability and the superior qualities of multiple-choice test items are realized most fully when care is taken in their construction. This involves formulating a clearly stated problem, identifying plausible alternatives, and removing irrelevant clues to the answer. The following suggestions provide more specific maxims for this purpose. 1. The stem of the item should be meaningful by itself and should present a definite problem. Often the stems of test items placed in multiple-choice form are incomplete statements that make little sense until all of the alternatives have been read. These are not multiple-choice items but, rather, a collection of true-false statements placed in multiple-choice form. A properly constructed multiple-choice item presents a definite problem in the stem that is meaningful without the alternatives. Compare the stems in the two versions of the test item in the following example:

EXAMPLE Poor: South America A is a flat, arid country. B imports coffee from the United States. C has a larger population that the United States. (D) was settled mainly by colonists from Spain. Better: Most of South America was settled by colonists from A England. B France. C Holland. (D) Spain.

Formulating a definite problem in the stem not only improves the stem of the item but also has a desirable effect on the alternatives. In the preceding example, the alternatives in the first version are concerned with widely dissimilar ideas. This heterogeneity is possible because of the stem's lack of structure. In the second version, the clearly formulated problem in the stem forces the alternatives to be more homogeneous. A good check on the adequacy of the problem statement is to cover the alternatives and read the stem by itself. It should be complete enough to serve as a short-answer item. Starting each item stem as a direct question and shifting to the incomplete statement form only when greater conciseness is possible is the most effective method for obtaining a clearly formulated problem. 2. The item stem should include as much of the item as possible and should be free of irrelevant material. This will increase the probability of a clearly stated problem in the stem and will reduce the reading time required. The following example illustrates how the conciseness of an item is increased by removing irrelevant material and including in the stem those words repeated in the alternatives. Notice that to obtain the conciseness of the final version, it is necessary to shift to the incomplete-statement form. The best version provides a slim-trim item that is easily read and focuses directly on the key element in the intended learning outcome:

EXAMPLE Poor: Most South America was settled by colonists from Spain. How would you account for the large number of Spanish colonists settling there?

1 A They were adventurous. (B) They were in search of wealth. C They wanted lower taxes. D They were seeking religious freedom. Better: Why did the Spanish colonists settle most of South America? A They were adventurous. (B) They were in search of wealth. C They wanted lower taxes. D They were seeking religious freedom. Best: Spanish colonists settled most of South America in search of A adventure. (B) wealth. C lower taxes. D religious freedom.

There are a few exceptions to this rule. In testing problem-solving ability, irrelevant material might be included in the stem of an item to determine whether students can identify and select the material that is relevant to the problem's solution. Similarly, repeating common words in the alternatives is sometimes necessary for grammatical consistency or greater clarity. 3. Use a negatively stated stem only when significant learning outcomes require it. Most problems can and should be stated in positive terms. This avoids the possibility of students' overlooking no, not, least, and similar words used in negative statements. In most instances, it also avoids measuring relatively insignificant learning outcomes. Knowing the least important method, the principle that does not apply, or the poorest reason are seldom important learning outcomes. We are usually interested in students' learning the most important method, the principle that does apply, and the best reason. Teachers sometimes go to ridiculous extremes to use negatively stated items because they appear more difficult. The difficulty of such items, however, is in the lack of sentence clarity rather than in the difficulty of the concept being measured:

EXAMPLE Poor: Which one of the following states is not located north of the Mason-Dixon line? A Maine B New York C Pennsylvania (D) Virginia Better: Which one of the following states is located south of the Mason-Dixon line? A Maine B New York C Pennsylvania (D) Virginia

Both versions of this item measure the same knowledge. But some students who can answer the second version correctly will select an incorrect alternative on the first version merely

2 because the negative phrasing confuses them. Such items thus introduce factors that contribute to the invalidity of the test. Although negatively stated items are generally to be avoided, there are occasions when they are useful, mainly in areas in which the wrong information or wrong procedure can have dire consequences. In the health area, for example, there are practices to be avoided because of their harmful nature. In shop and laboratory work, there are procedures that can damage equipment and result in bodily injury. And in driver training there are unsafe practices to be emphasized. When the avoidance of such potentially harmful practices is emphasized in teaching, it might well receive a corresponding emphasis in testing through the use of negatively stated items. When used, the negative aspects of the item should be made obvious:

EXAMPLE Poor: Which one of the following is not a safe driving practice on icy roads? A Accelerating slowly (B) Jamming on the brakes C Holding the wheel firmly D Slowing down gradually Better: All of the following are safe driving practices on icy roads Except A Accelerating slowly (B) Jamming on the brakes C Holding the wheel firmly D Slowing down gradually

In the first version of the item, the not is easily overlooked, in which case students would tend to select the first alternative and not read any further. In the second version, no student would probably overlook the negative element because it is placed at the end of the statement and is capitalized. 4. All of the alternatives should be grammatically consistent with the stem of the item. In the following examples, note how the better version results from a change in the alternatives in order to obtain grammatical consistency. This rule is not presented merely to perpetuate proper grammar usage, however; its main function is to prevent irrelevant clues from creeping in. All too frequently the grammatical consistency of the correct answer is given attention but that of the distracters is neglected. As a result, some of the alternatives are grammatically inconsistent with the stem and are therefore obviously incorrect answers:

EXAMPLES Poor: An electric transformer can be used A for storing electricity. (B) to increase the voltage of alternating current. C it converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. D alternating current is changed to direct current. Better: An electric transformer can be used to A store electricity. (B) increase the voltage of alternating current. C convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. D change alternating current to direct current.

3 Similar difficulties arise from a lack of attention to verb tense, to the proper use of the articles a or an, and to other common sources of grammatical inconsistency. Because most of these errors are the result of carelessness, they can be detected easily by carefully reading each item before assembling them into a test. See "How Many Alternatives Should Be Used in Multiple-Choice Items?" for more guidelines on constructing multiple-choice assessments.

How Many Alternatives Should Be Used in Multiple-Choice Items?

There is no magic number of alternatives to use in a multiple-choice item. Typically three, four, or five choices are used. Some favor five-choice items to reduce the chances of guessing the correct answer. Number of Chances of a Chance Score Choices Correct Guess on 100-Item Test Five-choice items 1 in 5 20 Four-choice items 1 in 4 25 Three-choice items 1 in 3 33

Reducing the chances of guessing the correct answers by adding alternatives enhances reliability and validity, but only if all the distracters are plausible and the items are well constructed. Our preference is for using four-choice items because, with reasonable effort, three good distracters usually can be obtained (a fourth distracter tends to be difficult to devise and is usually weaker than the others). For young students, three-choice items may be preferable in order to reduce the amount of reading. It should also be noted that there is a tradeoff between the number of items and the number of choices per item. A fifty-item test with three choices per item is likely to produce a more valid and reliable test than forty-item test with five choices per item, especially if the fourth distractor is not very plausible for many of the items. The number of alternatives can, of course, vary from item to item. You might use a five-choice item when four good distracters are available and a three-choice item when there are only two. Don't give up too soon in constructing distracters, however. It takes time and effort to generate several good ones.

5. An item should contain only one correct or clearly best answer. Including more than one correct answer in a test item and asking students to select all of the correct alternatives has two shortcomings. First, such items are usually no more than a collection of true-false items presented in multiple-choice format. They do not present a definite problem in the stem, and the selection of answers requires a mental response of true or false to each alternative rather than a comparison and selection of alternatives. Second, because the number of alternatives selected as correct answers varies from one student to another, satisfactory scoring methods are more cumbersome than most teachers are likely to want to use or have to explain to students:

EXAMPLE Poor: The state of Michigan borders on (A) Lake Huron. B Lake Ontario. (C) Indiana.

4 D Illinois.

Better: The state of Michigan borders on A Lake Huron. (T) F B Lake Ontario. T (F) C Indiana. (T) F D Illinois. T (F)

The second version of this item shows students what type of response is expected. They are to read each alternative and decide whether it is true or false. Thus, this is not a four- alternative, multiple-choice item, but a series of four statements, each of which has two alternatives—true or false. This second version, which is called a cluster-type true-false item, not only identifies the mental process involved, but simplifies the scoring. Each statement in the cluster can be considered as one point and scored as any other true-false item is scored. In contrast, how would you score a student who selected alternatives A, B, and C in the first version? Would you give two points for the response because two answers were correctly identified? Would you give only one point because one incorrect alternative was also selected? Or would you give no points because the answer as a whole was not completely correct? How would you evaluate the lack of a response to Alternative D? Assume that the student knew Illinois did not border on Michigan and therefore did not select it, or assume that the student was uncertain and left it blank. Fairly complicated and cumbersome scoring rules are required to satisfactorily resolve these problems. Hence, multiple-choice items like the one in the first version should be avoided or converted to the true-false form. There is another important facet of this rule concerning single-answer multiple-choice items: the answer must be agreed upon by authorities in the area. The best-answer type item is especially subject to variations of interpretation and disagreement concerning the correct answer. Care must be taken to make certain that the answer is clearly the best one. Frequently, rewording the problem in the stem will correct an otherwise faulty item. In the first version of the following item, different alternatives could be defended as correct, depending on whether the best refers to cost, efficiency, cleanliness, or accessibility. The second version avoids this problem by making the criterion of best explicit:

EXAMPLE Poor: Which one of the following is the best source of heat for home use? A Coal B Electricity C Gas D Oil Better: In the midwestern part of the United States, which one of the following is the most economical source of heat for home use? (A) Coal B Electricity C Gas D Oil

6. Items used to measure understanding should contain some novelty, but beware of too much. The construction of multiple-choice items that measure understanding requires a

5 careful choice of situations and skillful phrasing. The situations must be new to the students, but not too far removed from the examples used in class. If the test items contain problem situations identical with those used in class, the students can, of course, respond on the basis of memorized answers. On the other hand, if the problem situations contain too much novelty, some students may respond incorrectly merely because they lack necessary factual information about the situations used. Asking students to apply the law of supply and demand to some phase of banking, for example, would be grossly unfair if they had not had a previous opportunity to study banking policies and practices. They may have a good understanding of the law of supply and demand but be unable to demonstrate this because of their unfamiliarity with the particular situation selected. The problem of too much novelty usually can be avoided by selecting situations from the student's everyday experiences, by including in the stem of the item any factual information needed, and by phrasing the item so that the type of application or interpretation called for is clear. 7. All distracters should be plausible. The purpose of a distracter is to distract the uninformed from the correct answer. To the student who has not achieved the learning outcome being tested, the distracters should be at least as attractive as the correct answer and preferably more so. In a properly constructed multiple-choice item, each distracter will be elected by some students. If a distracter is not selected by anyone, it is not contributing to the functioning of the item and should be eliminated or revised. One factor contributing to the plausibility of distracters is their homogeneity. If all of the alternatives are homogeneous with regard to the knowledge being measured, the distracters are more likely to function as intended. Whether alternatives appear homogeneous and distracters plausible, however, also depends on the students' age level. Note the difference in homogeneity in the following two items:

EXAMPLE Poor: Who discovered the North Pole? A Christopher Columbus B Ferdinand Magellan (C) Robert Peary D Marco Polo Better: Who discovered the North Pole? A Roald Amundsen B Richard Byrd (C) Robert Peary D Robert Scott

The first version would probably appear homogeneous to students at the primary level because all four choices are the names of well-known explorers. However, students in higher grades would eliminate alternatives A, B, and D as possible answers because they would know these men were not polar explorers. They might also recall that these men lived several hundred years before the North Pole was discovered. In either case, they could quickly obtain the correct answer by the process of elimination. The second version includes only the names of polar explorers, all of whom were active at approximately the same time. This homogeneity makes each alternative much more plausible and the elimination process much less effective. It also, of course, increases the item's level of difficulty. See the accompanying "Guidelines" box.

6 In selecting plausible distracters, the students' learning experiences must not be ignored. In the foregoing item, for example, the distracters in the second version would not be plausible to students if Robert Peary was the only polar explorer they had studied. Obviously, distracters must be familiar to students before they can serve as reasonable alternatives. Less obvious is the rich source of plausible distracters provided by the students' learning experiences. Common misconceptions, errors of judgment, and faulty reasoning that occur during the teaching--learning process provide the most plausible and educationally sound distracters available. One way to tap this supply is to keep a running record of such errors. A quicker method is to administer a short- answer test to students and tabulate the most common errors. This provides a series of incorrect responses that are especially plausible because they are in the students' own language.

GUIDELINES Ways to Make Distracters Plausible

1. Use the students' most common errors.

2. Use important-sounding words (e.g., significant, accurate) that are relevant to the item stem. But don't overdo it!

3. Use words that have verbal associations with the item stem (e.g., politician, political).

4. Use textbook language or other phraseology that has the appearance of truth.

5. Use incorrect answers that are likely to result from student misunderstanding or carelessness (e.g., forgets to convert from feet to yards).

6. Use distracters that are homogeneous and similar in content to the correct answer (e.g., all are inventors).

7. Use distracters that are parallel in form and grammatically consistent with the item's stem.

8. Make the distracters similar to the correct answer in length, vocabulary, sentence structure, and complexity of thought.

Caution: Distracters should distract the uninformed, but they should not result in trick questions that mislead knowledgeable students (e.g., don't insert not in a correct answer to make it a distracter).

8. Verbal associations between the stem and the correct answer should be avoided. Frequently a word in the correct answer will provide an irrelevant clue because it looks or sounds like a word in the stem of the item. Such verbal associations should never permit the student who lacks the necessary achievement to select the correct answer. However, words similar to those in the stem might be included in the distracters to increase their plausibility. Students who depend

7 on rote memory and verbal associations will then be led away from, rather than to, the correct answer. The following item, taken from a fifth-grade test on a weather unit, shows the incorrect and correct use of verbal associations between the stem and the alternatives:

EXAMPLE Poor: Which one of the following agencies should you contact to find out about a tornado warning in your locality? A State farm bureau (B) Local radio station C United States Post Office D United States Weather Bureau Better: Which one of the following agencies should you contact to find out about a tornado warning in your locality? A Local farm bureau (B) Nearest radio station C Local post office D United States Weather Bureau

In the first version, the association between locality and local is an unnecessary clue. In the second version, this verbal association is used in two distracters to make them more attractive choices. But if irrelevant verbal associations in the distracters are overused, students will soon catch on and avoid alternatives with pat verbal associations. 9. The relative length of the alternatives should not provide a clue to the answer. The best we can hope for in equalizing the length of a test item's alternatives is to make them approximately equal. But because the correct answer usually needs to be qualified, it tends to be longer than the distracters unless a special effort is made to control the length of the alternatives. If the correct answer cannot be shortened, the distracters can be expanded to the desired length. Lengthening the distracters also is desirable for another reason. Added qualifiers and greater specificity frequently contribute to their plausibility. The correct answer should not be consistently longer, or consistently shorter, or consistently of medium length. The relative length of the correct answer should vary from one item to another in such a manner that no pattern is discernible to indicate the answer. This means, of course, that sometimes the correct answer will be the longest:

EXAMPLE Poor: What is the major purpose of the United Nations? (A) To maintain peace among the peoples of the world B To establish international law C To provide military control D To form new governments Better: What is the major purpose of the United Nations? (A) To maintain peace among the peoples of the world. B To develop a new system of international law. C To provide military control of nations that have recently attained their independence D To establish and maintain democratic forms of government in newly formed nations

8 10. The correct answer should appear in each of the alternative positions an approximately equal number of times but in random order. Some teachers often bury the correct answer in the middle of the list of alternatives. As a consequence, the correct answer appears in the first and last positions far less often than it does in the middle positions. This, of course, provides an irrelevant clue to the alert student. In placing the correct answer in each position approximately an equal number of times, care must be taken to avoid a regular pattern of responses. A random placement of correct answers can be attained with the use of any book. For each test item, open the book at an arbitrary position, note the number on the right-hand page, and place the correct answer for that test item as follows: If Page Number Place Correct Ends in Answer 1 First 3 Second 5 Third 7 Fourth 9 Fifth

11. Use sparingly special alternatives such as "none of the above" or "all of the above." The phrases "none of the above" or "all of the above" are sometimes added as the last alternative in multiple-choice items. This is done to force the student to consider all of the alternatives carefully and to increase the difficulty of the items. All too frequently, however, these special alternatives are used inappropriately. In fact, there are relatively few situations in which their use is appropriate. The use of "none of the above" is restricted to correct-answer type multiple-choice items and consequently to the measurement of factual knowledge to which absolute standards of correctness can be applied. It is inappropriate in best-answer-type items because the student is told to select the best of several alternatives of varying degrees of correctness. Use of "none of the above" is frequently recommended for items measuring computational skill in mathematics and spelling ability. But these learning outcomes generally should not be measured by multiple-choice items, because they can be measured more effectively by short-answer items. When "none of the above" is used in such situations, the item may measure nothing more than a student's ability to recognize incorrect answers, a rather inadequate basis for judging computational skill or spelling ability. The alternative "none of the above" should be used only when the measurement of significant learning outcomes requires it. As with negatively stated item stems, sometimes procedures or practices should be avoided for safety, health, or other reasons. When knowing what not to do is important, "none of the above" might be appropriately applied. When used for this purpose, it also must be used as an incorrect answer a proportionate number of times. See the following box. The use of "all of the above" is fraught with so many difficulties that it might best be discarded as a possible alternative. When used, some students will note that the first alternative is correct and select it without reading further. Other students will note that at least two of the alternatives are correct and thereby know that "all of the above" must be the answer. In the first instance, students mark the item incorrectly because they do not read all of the alternatives, and

9 in the second instance, students obtain the correct answer on the basis of partial knowledge. Both types of response prevent the item from functioning as intended.

Examples of Misuse of the Alternative "None of the Above"

Which of the following is not an example of a mammal? (A) Bird B Dog C Whale D None of the above (It would be easy to prove that "D" is not an example of a mammal.)

When the temperature drops, tire pressure tends to (A) Decrease B Increase C Stay the same D None of the above (There may be something other than A, B, or C, but we can't think of what it might be.)

United States federal law requires that first offenders must be fined or imprisoned if they possess A Amphetamine B Heroin C Marijuana (D) None of the above (Sounds like a very unfair law. If you don't agree, read only the stem and answer "D.")

12. Do not use multiple-choice items when other item types are more appropriate. When various item types can serve a purpose equally well, the multiple-choice item should be favored because of its many superior qualities. Sometimes, however, the multiple-choice form is inappropriate or less suitable than other item types. When there are only two possible responses (e.g., fact or opinion), the true-false item is more appropriate. When there are enough homogeneous items but few plausible distracters for each, a matching exercise might be more suitable. In certain problem-solving situations in mathematics and science, for example, supply- type short-answer items are clearly superior. The measurement of many complex achievement goals (such as organizing, integrating, and expressing ideas; the formulation and testing of hypotheses; or the construction of models, maps, or diagrams) requires the use of performance- based assessment tasks. Although we should take full advantage of the wide applicability of the multiple-choice form, we should not lose sight of a principle of test construction cited earlier-- select the item type that measures the learning outcome. See “Checklist” box.

CHECKLIST Reviewing Multiple-Choice Items Yes No 1. Is this the most appropriate type of item to use? ______

10 2. Does each item stem present a meaningful problem? ______

3. Are the item stems free of irrelevant material? ______

4. Are the item stems stated in positive terms (if possible)? ______

5. If used, has negative wording been given special emphasis (e.g., capitalized)? ______

6. Are the alternatives grammatically consistent with the item stem? ______

7. Are the alternative answers brief and free of unnecessary words? ______

8. Are the alternatives similar in length and form? ______

9. Is there only one correct or clearly best answer? ______

10. Are the distracters plausible to low achievers? ______

11. Are the items free of verbal clues to the answer? ______

12. Are verbal alternatives in alphabetical order? ______

13. Are numerical alternatives in numerical order? ______

14. Have none of the above and all of the above been avoided (or used sparingly and appropriately)? ______

15. If revised, are the items still relevant to the intended learning outcomes? ______

16. Have the items been set aside for a time before reviewing them? ______

11 APPENDIX C: SUGGESTIONS FOR CONSTRUCTING ESSAY QUESTIONS From Linn/Miller, Measurement and Assessment in Teaching, 9e

The improvement of the essay question as a measure of complex learning outcomes requires attention to two problems: (a) how to construct essay questions that call forth the desired student responses and (b) how to score the answers so that achievement is reliably measured. Here we shall suggest ways of constructing essay questions, and in the next section, we shall suggest ways of improving scoring, although these two procedures are interrelated.

Some Types of Thought Questions and Sample Item Stems

Comparing Persuading Describe the similarities and differences Write a letter to the principal get approval between . . . for a class field trip to the state capital. Compare the following two methods for . . . Why should the student newspaper be allowed to decide what should be printed without Relating cause and effect prior approval from teachers? What are major causes of . . .? What would be the most likely effects of . . .? Classifying Group the following items according to . . . Justifying What do the following items have in Which of the following alternatives would you common? favor, and why? Explain why you agree or disagree with the Creating following statement. List as many ways as you can think of for . . . Make up a story describing what would Summarizing happen if . . . State the main points included in . . . Briefly summarize the contents of . . . Applying Using the principle of. . .as a guide, Generalizing describe how you would solve the Formulate several valid generalizations from the following problem situation. following data. Describe a situation that illustrates the State a set of principles that can explain principle of . . . the following events. Analyzing Inferring Describe the reasoning errors in the In light of the facts presented, what is most following paragraph. likely to happen when ...? List and describe the main characteristics of . . . How would Senator X be likely to react to the following issue? Synthesizing Describe a plan for proving that . . . Explaining Write a well-organized report that Why did the candle go out shortly after it was shows. . . covered by the jar? Explain what President Truman meant Evaluating when he said “If you can’t stand the Describe the strengths and weaknesses of . . . heat, get out of the kitchen.” Using the given criteria, write an evaluation of . . .

12 1. Restrict the use of essay questions to those learning outcomes that cannot be measured satisfactorily by objective items. Other things being equal, objective measures have the advantage of efficiency and reliability. But when objective items are inadequate for measuring the learning outcomes, the use of essay questions can be easily defended, despite their limitations. Some of the complex learning outcomes, such as those pertaining to the organization, integration, and expression of ideas, will be neglected unless essay questions are used. By restricting the use of essay questions to these areas, the evaluation of student achievement can be most fully realized. 2. Construct questions that will call forth the skills specified in the learning standards. Like objective items, essay questions should measure the achievement of clearly defined content standards or instructional outcomes. If the ability to apply principles is being measured, for example, the questions should be phrased in such a manner that they require student to display their conceptual understanding or a particular skill. Essay questions should never be hurriedly constructed in the hope that they will measure broad, important (but unidentified) educational goals. Each essay question should be carefully designed to require students to demonstrate achievement defined in the desired learning outcomes. See "Some Types of Thought Questions and Sample Item Stems" for examples of the many types of questions that might be asked; the phrasing of any particular question will vary somewhat from one subject to another. Constructing essay questions in accordance with particular learning outcomes is much easier with restricted-response questions than with extended-response questions. The restricted scope of the topic and the type of response expected make it possible to relate a restricted-response question directly to one or more of the outcomes. The extreme freedom of the extended-response question makes it difficult to present questions so that the student's responses will reflect the particular learning outcomes desired. This difficulty can be partially overcome by indicating the bases on which the answer will be evaluated:

EXAMPLE Write a two-page statement defending the importance of conserving our natural resources. (Your answer will be evaluated in terms of its organization, its comprehensiveness, and the relevance of the arguments presented.)

Informing students that they should pay special attention to organization, comprehensiveness, and relevance of arguments defines the task, makes the scoring criteria explicit, and makes it possible to key the question to a particular set of learning outcomes. These directions alone will not, of course, ensure that the appropriate behaviors will be exhibited. It is only when the students have been taught the relevant skills and how to integrate them that such directions will serve their intended purpose. 3. Phrase the question so that the student's task is clearly indicated. The purpose a teacher had in mind when developing the question may not be conveyed to the student if the question contains ambiguous phrasing. Students interpret the question differently and give a hodgepodge of responses. Because it is impossible to determine which of the incorrect or off-target responses are due to misinterpretation and which to lack of achievement, the results are worse than worthless: They may actually be harmful if used to measure student progress toward instructional objectives.

13 One way to clarify the question is to make it as specific as possible. For the restricted-response question, this means rewriting it until the desired response is clearly defined:

EXAMPLE Poor: Why do birds migrate? Better: State three hypotheses that might explain why birds migrate south in the fall. Indicate the most probable one and give reasons for your selection.

The improved version presents the students with a definite task. Although some students may not be able to give the correct answer, they all will certainly know what type of response is expected. Note also how easy it would be to relate such an item to a specific learning outcome such as "the ability to formulate and defend tenable hypotheses." When an extended-response question is desired, some limitation of the task may be possible, but care must be taken not to destroy the function of the question. If the question becomes too narrow, it will be less effective as a measure of the ability to select, organize, and integrate ideas and information. The best procedure for clarifying the extended-response question seems to be to give the student explicit directions concerning the type of response desired:

EXAMPLE Poor: Compare the Democratic and Republican parties. Better: Compare the current policies of the Democratic and Republican parties with regard to the role of government in private business. Support your statements with examples when possible. (Your answer should be confined to two pages. It will be evaluated in terms of the appropriateness of the facts and examples presented and the skill with which it is organized.)

The first version of the example offers no common basis for responding and, consequently, no frame of reference for evaluating the response. If students interpret the question differently, their responses will be organized differently, because organization is partly a function of the content being organized. Also, some students will narrow the problem before responding, thus giving themselves a much easier task than students who attempt to treat the broader aspects of the problem. The improved version gives students a clearly defined task without destroying their freedom to respond in original ways. This is achieved both by specifying the scope of the question and by including directions concerning the type of response desired. See "The Importance of Writing Skill."

The Importance of Writing Skill

14 Performance on an essay test depends largely on writing ability. If students are to be able to demonstrate the achievement of higher-level learning outcomes, they must be taught the thinking and writing skills needed to express themselves. This means teaching them how to select relevant ideas, how to compare and relate ideas, how to organize ideas, how to apply ideas, how to infer, how to analyze, how to evaluate, and how to write a well-constructed response that includes these elements. Asking students to "compare," "interpret," or "apply" has little meaning unless they have been taught how to do these things. This calls for direct teaching and practice in writing, in an atmosphere that is less stressful than an examination period. Use of analytic scoring criteria that give separate scores for characteristics such as the quality of ideas, use of examples, use of supporting evidence and ones dealing with writing mechanics such as grammar, punctuation, spelling can improve scoring and, if communicated to students, can both guide their efforts in constructing essays and lead to improvements of specific writing skills.

4. Indicate an approximate time limit for each question. Too often essay questions place a premium on speed, because inadequate attention is paid to reasonable time limits during the test's construction. As each question is constructed, the teacher should estimate the approximate time needed for a satisfactory response. In allotting response time, keep the slower students in mind. Most errors in allotting time needed are in giving of too little time. It is better to use fewer questions and give more generous time limits than to put some students at a disadvantage. The time limits allotted to each question should be indicated to the students so that they can pace their responses to each question and not be caught at the end of the testing time with "just one more question to go." If the assessment contains both objective and essay questions, the students should, of course, be told approximately how much time to spend on each part of the test. This may be done orally or included on the test form itself. In either case, care must be taken not to create over-concern about time. The adequacy of the time limits might very well be emphasized in the introductory remarks, so as to allay any anxiety that might arise. 5. Avoid the use of optional questions. A fairly common practice when using essay questions is to give students more questions than they are expected to perform and then permit them to select a given number. For example, the teacher may include six essay questions in a test and direct the students to respond to any three of them. This practice is generally favored by students because they can select those questions they know most about. Except for the desirable effect on student morale, however, there is little to recommend the use of optional questions. If students answer different questions, it is obvious that they are taking different tests, and so the common basis for evaluating their achievement is lost. Each student is demonstrating the achievement of different learning outcomes. As noted earlier, even the ability to organize cannot be measured adequately without a common set of responses, because organization is partly a function of the content being organized. The use of optional questions might also influence the validity of the test results in another way. When students anticipate the use of optional questions, they can prepare responses on several topics in advance, commit them to memory, and then select questions to which the responses are most appropriate. During such advance preparation,

15 it is also possible for them to get help in selecting and organizing their response. Needless to say, this provides a distorted measure of the student's achievement, and it also tends to have an undesirable influence on study habits, as intensive preparation in a relatively few areas is encouraged. Of course, there are learning outcomes that involve in-depth study of topics that are shaped and defined by students. Evaluation of student work on topics of their own choosing is important for such learning outcomes. The assessment of such outcomes, however, is better approached through the assignment of projects than by an essay test. See the accompanying "Checklist" to evaluate essay questions you construct.

CHECKLIST

Reviewing Essay Questions

Yes No 1. Is this the most appropriate type of task to use? ______

2. Are the questions designed to measure higher-level learning outcomes? ______

3. Are the questions relevant to the intended learning outcomes? ______

4. Does each question clearly indicate the response expected? ______

5. Are students told the bases on which their answers will be evaluated? ______

6. Are generous time limits provided for responding to the questions? ______

7. Are students told the time limits and/or point values for each question? ______

8. Are all students required to respond to the same questions? ______

9. If revised, are the questions still relevant to the intended learning outcomes? ______

10. Have the questions been set aside for a time before reviewing them? ______

16