Educational Technology Expertise Center Open University of the Netherlands

Research project proposal

This project falls in the following research topic(s):

Design □ Competency analysis / domain modeling □ Learning tasks & learner support Delivery □ Composing instructional messages □ Computer-mediated communication Diagnosis ■ Performance-based assessment □ Quality control & assurance

1 Project chair Project chair: Dr. Th. J. Bastiaens Function: Educational Technologist Department: OTEC Telephone: 045-5762797 Email: [email protected]

2 Project title English: The perception of authentic assessment and its role in the learning process Dutch: De perceptie van authentieke toetsing en de invloed daarvan op hoe er geleerd wordt

3 Place in the organization OTEC

4 Synopsis of the research problem English Important social and theoretical changes with respect to learning are at the root of the increasing interest in authentic learning and authentic assessment. Authentic tasks in an educational setting are assignments that have a real- world application, bear a strong resemblance to task performed in a non educational setting (such as the home, an organization or the workplace) and require students to apply a broad range of knowledge and skills. Learning with authentic tasks changes the shape of the educational experience for students therefore also the ways that have been used previously to evaluate successful student learning need to undergo a shift as well. This research project focuses on these new ways of evaluating student learning (also called authentic assessment methods). The ideas of instructional designers about authentic assessment are often based on other related (and popular) evaluation methods. But there is no integrated instructional design theory about authentic assessment. What instructional designers and developers in reality do is borrow ideas and guidelines from different educational, psychological, social, and design theories. The proposed research looks more closely at these borrowed ideas and combinations of theories. What are the underlying ideas of developing authentic assessment and learning tasks and how do learners perceive it? There is an interaction / reciprocal relationship between (the perception of) assessment and the way the perceiver learns. If the learner knows or expects that (s)he will be tested in a certain way, the learner will adapt his/her learning to satisfy that expectation, regardless of the way the instruction is designed and presented. This so called ‘backwash effect’ (Prodromou, 1995) says that the way learning is assessed determines the way the learner will study and learn. The current shift from objectivist, didactic teaching to more constructivist, competency based learning and training requires testing and assessment that, on the one hand can determine if the 1 competencies have been achieved and, on the other hand stimulate – or at least don’t deter – that type of learning. This project is focused on determining: Are current assessment methods sufficient for assessing competencies and their underlying knowledge, skills, and attitudes? What are the perceptions, opinions/beliefs of students with respect to (authentic) assessment? What are their preferences with respect to types of (authentic) assessment? How does the authenticity of an assessment method influence student perceptions, opinions/beliefs and preferences? What is the effect of different methods of (authentic) assessment on what is learned and how it is learned?

Dutch Belangrijke sociale en theoretische veranderingen op het gebied van leren liggen ten grondslag aan de stijgende interesse voor authentiek leren en authentieke assessment. Authentieke taken in een onderwijssetting zijn opdrachten met een hoog realiteitgehalte, dit wil zeggen ze lijken sterk op taken uit de praktijk buiten de onderwijsomgeving (thuis, een organisatie of de werkplek). De taken eisen van studenten dat ze een brede schakering van kennis en vaardigheden inzetten in een realistische context. Leren met authentieke taken is een onderwijskundige verandering die de onderwijservaringen van studenten verandert, maar daarmee in toenemende mate ook vraagt voor andere manieren van evalueren en toetsen. In dit project richten we ons op deze andere en nieuwe manieren van evalueren en toetsen van resultaten, ook wel authentieke assessment methoden genoemd. De ideeën van ontwerpers over authentieke assessment methoden zijn vaak gebaseerd op bestaande (populaire) evaluatiemethoden. Er is namelijk geen geïntegreerde ontwerp theorie voor authentieke assessment. In de praktijk lenen ontwerpers ideeën en richtlijnen van verschillende onderwijskundige-, psychologische-, sociale- en ontwerptheorieën. Het beoogde onderzoek gaat nauwkeurig kijken naar die geleende ideeën en combinaties van theorieën. Wat zijn de onderliggende gedachten bij het ontwerpen van authentieke assessment en leertaken en hoe wordt dit ervaren door de studenten. Er bestaat namelijk een interactie/ wederkerige relatie tussen (de perceptie van) assessment methoden en de manier waarop studenten leren. Als de student weet of verwacht op welke manier hij getoetst zal worden dan zal hij zijn leren aanpassen aan de toetsing om aan de verwachtingen te voldoen. De vorm en presentatie van de instructie heeft dan geen invloed meer. Dit zogenoemde ‘terugloop effect’ (Prodromou, 1995) gaat ervan uit dat de toetsing van het leerproces bepaalt hoe de student zal leren en studeren. De huidige verschuiving van objectivistisch, didactisch onderwijzen naar meer constructivistisch, competentiegericht leren vereist toets- en evaluatiemethoden die aan de ene kant kunnen achterhalen of competenties zijn bereikt en aan de andere kant (competentiegericht) leren stimuleren. Dit onderzoek is gericht op het bepalen: of de huidige assessment methoden voldoen voor het competentiegericht leren en haar onderliggende kennis, vaardigheden en attitudes wat de werkelijke percepties en meningen van studenten zijn inzake (authentieke) assessment. van eventuele voorkeuren van typen (authentieke) assessment in hoeverre de authenticiteit van een assessment methode de perceptie en meningen van studenten beïnvloed. van de effecten van de verschillende assessment methoden op wat er geleerd wordt en hoe er geleerd wordt.

5 Research team

Name and titles Expertise / Function Dept. Project chair Dr. Th.J. Bastiaens Senior educational technologist OTEC Researcher AiO Psychology / Education OTEC Other members Dr. R. Martens Senior educational technologist OTEC Ph.D. supervisor Prof. Dr. P.A. Kirschner Professor of educational technology OTEC Consultants OTEC

2 6 Length of the project Begin date: September 2002 End date: September 2006 Total length: 48 months

7 Intended output Publications and conference presentations 3 publications (minimum) in SSCI/ICO-journals Ph.D. thesis Papers at two international conferences (e.g., AERA) Papers at two European conferences (e.g., EARLI) Papers at three national conferences (ORD)

Instruments and procedures Assessment Perception Inventory Study and Learning Behavior Inventory

8 Further elaboration a. Further elaboration of the problem and aims of the research project Important social and theoretical changes with respect to learning are at the root of the increasing interest in authentic learning and authentic assessment. The first is the view of learning that considers both the social context and the social processes as an integral part of the learning activity (Situated cognition: Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989). The second is the recognition of the importance of learners actively constructing their knowledge as suggested by the theoretical viewpoint of constructivism (Jonassen, 1993). As a consequence, increasing attention is paid to a learner-centered curriculum, problem based- and contextual learning (Brown, 1998). In a learner-centered curriculum, learners work in collaboration with others, including the teacher. Problem based learning is best to describe with the four critical features: the problematic situation always opens a investigation; the problem is often – just as reality - ill structured; students are the problem solvers who generate solutions and assessment is used as both a structure for reflection and a measure of learning. Contextual learning is a strategy for helping students to construct knowledge and meaning from new information though the complex interactions of teaching methods, content, situations and timing (National school-to-work opportunities office, 1996). Knowledge is socially shared and learning is situation specific. Together these approaches result in learning with authentic tasks. Authentic tasks in an educational setting are assignments that have a real- world application, bear a strong resemblance to task performed in a non educational setting (such as the home, an organization or the workplace) and require students to apply a broad range of knowledge and skills (Wiggins, 1989; Wolf, 1989). The approach to pose authentic tasks to the learner within the context of the learners interest, also called situated learning, involves the acquisition of knowledge and skills in the situation in which they will be used. Authentic tasks usually involve multiple disciplines and are challenging in their complexity. Higher order thinking skills, such as comprehension, design, analysis and problem solving are typically and important components of authentic learning.

These changes in the definition of learning, the curriculum, and the classroom context lead to the need for authentic assessment. If indeed the shape of the educational experience for students is being changed, the ways that have been used previously to evaluate successful student learning need to undergo a shift as well. This research project focuses in these new ways of evaluating student learning (also called authentic assessment methods).

Guidelines also for the development of authentic assessment? The ideas of instructional designers about authentic assessment are often based on other related (and popular) evaluation methods. Authentic assessment is also often called "performance," alternative," or "direct" assessments, it can include a wide variety of evaluation techniques: written products, solutions to problems, experiments, exhibitions, performances, portfolios of work, checklists and inventories, and cooperative group projects. But there is no

3 integrated instructional design theory about authentic assessment. What instructional designers and developers in reality do is borrow ideas and guidelines from different educational, psychological, social, and design theories. Even vaguer are the empirical foundations that underlie assumptions of authentic assessment and how it affects study and learning. Earlier research on this (e.g., Martens, Valcke & Portier, 1997; Martens 1998) has shown that very often course designers have serious misconceptions about how students actually perceive learning and evaluation methods and materials. For example it is well accepted that that what is tested determines what is learned. This is a typical example of “the tail wagging the dog” or the so-called “backwash effect” of assessment on learning (Prodromou, 1995). Research has shown that these effects are so strong that they can undermine, threaten or even negate the effects of education based upon constructivist philosophy (Sambell & Johnson, 1998). Another fact is that students in ‘real life’ students have there own ‘hidden curriculum’, ‘adopting ploys and strategies to survive in the system.’ (Lockwood, 1995, p. 197). Designers often do not know how students perceive their courses, materials and evaluation methods. On the other hand, assessment can indeed be used as a positive tool for affecting learning (Heron, 1981, Boud 1990, Ramsden, 1992, Brown & Knight, 1994). The acquisition of competencies can be facilitated through the use of authentic learning tasks and meaningful and provocative assessment tasks (Birenbaum, 1996). In this way, assessment can have a positive 'backwash effect' (Biggs, 1996). The research proposed here tries to get to the root of this effect, namely to the role that perception of assessment plays in study and learning. The properties of objects (here the assessment) affect how they can be/are used and how people can use them. The relationship between the properties and the use is known as an affordance (Gibson, 1979; Gaver, 1991, 1996). Norman (1999) makes us aware that an affordance is ‘only as good as’ how it is perceived. If we see the assessment as an affordance to learning, then the perception of the learner (the perceived affordance) is of the highest importance. For example, a student asked to collaborate, but who is assessed c.q. perceives that (s)he will be assessed competitively will not truly collaborate. Collaboration costs time and effort which, in the learner’s mind, can better be spent on ‘just learning’ what (s)he needs to get a good grade.

Research supports that the perception of assessment influences learning behavior and learning results (Bennett & Ward, 1993; Gipps & James, 1996; Traub & MacRury, 1990; Zeidner, 1987). Frederiksen (1984) stated that there is no more powerful impulse to student learning than tests and examinations. If there is friction between the (perceived) goals of educational and the (perceived) goals of assessment, then it is inevitable that assessment will win. An educational innovation where the assessment remains the same, or is perceived to have not changed, is doomed to failure (Boud and Falchikov, 1989; McDowell, 1995; Topping, 1998; van der Vleuten, 1996). What is necessary, is to determine how assessment, and the perception thereof, influences studying and learning. Gipps and Jones (1996) state that assessment influences learning because it motivates learning, helps students decide what to learn, helps students learn how to learn, and helps students learn to judge the effectiveness of their learning. We, as educational designers and developers, assume that the way we design a learning situation (pedagogy, assessment, et cetera) is also the way it will be perceived and used by the learner. In competence based learning, we try to achieve what Honebein (1996) calls the seven “pedagogical goals” of constructivist learning environments, namely knowledge construction, appreciation of multiple perspectives, relevant contexts, ownership of the learning process, social experience, use of multiple representations, and self-consciousness / reflection. We then try to utilize new types of assessment congruent to the pedagogy and goals of instruction (Birenbaum, 1996; Reeves & Okey, 1996). Jonassen (1992), in presenting criteria for choosing a type of assessment places task authenticity, knowledge construction via collaboration, process of experiencing, and contextualization high on the list. With respect to these new types of assessment, the OUNL in general and OTEC in particular have begun making use of two types of assessment to reach its goals, namely portfolio assessment and peer-/co-assessment. Portfolio assessment uses specially collected original work in combination with personal accounts and reflections (the portfolio) that the learner composes under the guidance of the

4 institution and which are assessed, by assessors (Birenbaum, 1996; Montgomery, 1995; Spandel, 1997). Co-assessment asks different people to assess the processes and products of learning behavior. Co-assessment allows the learner to assess him/herself and others while the institution (through the teacher) still retains control over the situation (Hall, 1995). This choice also is in line with the choices made within at least two other OUNL research projects within the diagnosis theme namely: - The supportive function of performance-assessment in student learning and the development of competence (AiO proposal Vermetten & Jochems) - Electronic peer assessment during learning by design (Research project Kirschner, Prins, & Sluijsmans)

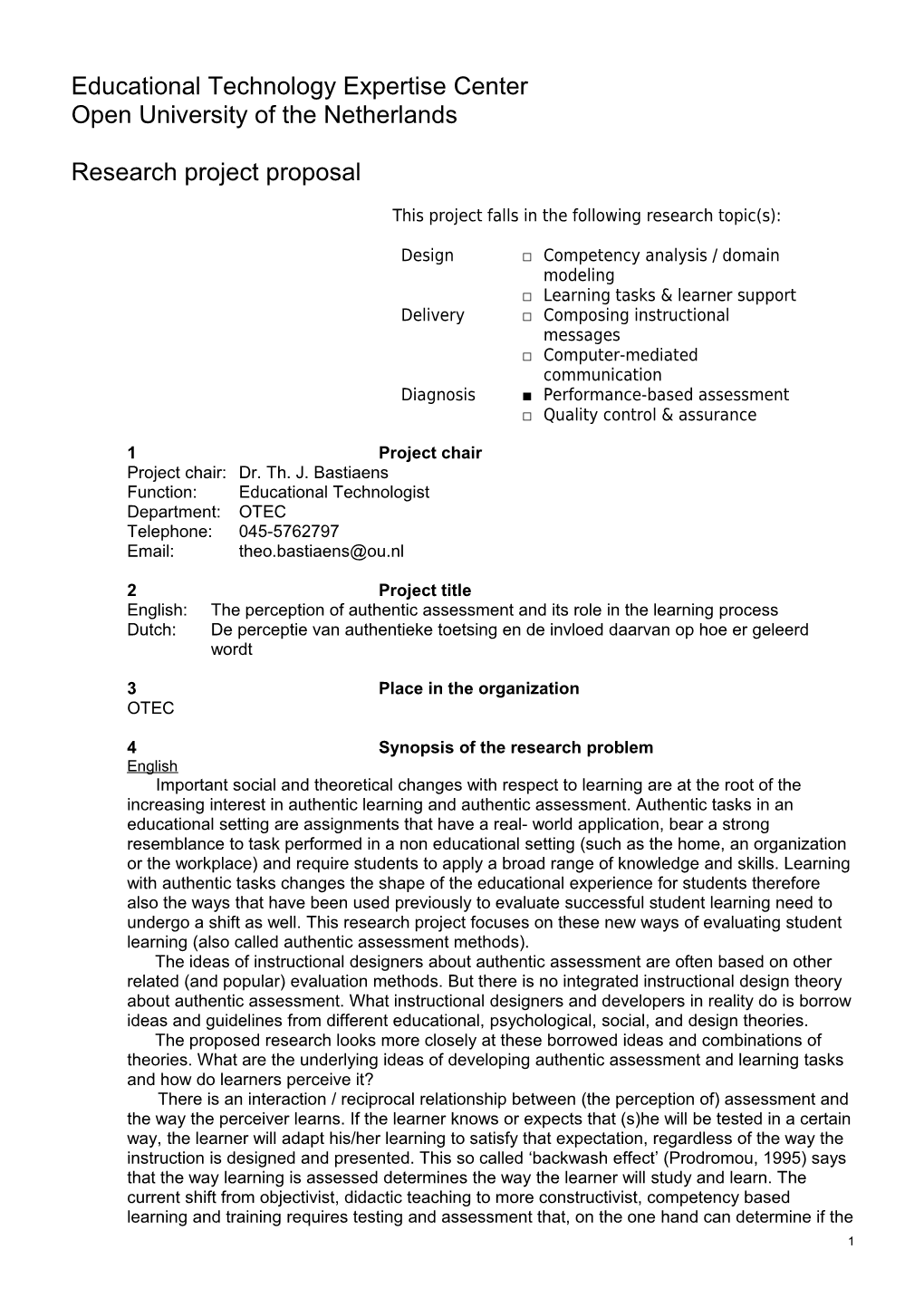

Finally, we strive to integrate learning and assessment (Dochy, et al., 1999). Glaser (1998) stated that assessment instruments can be degraded or enhanced by the environments where they are used and the skill of the professionals using them. Fundamental is the integration of teaching and assessment in instructional settings. This integration is in line with Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (1983). Gardner suggests that traditional education has emphasized the assessment of logical-mathematical and verbal-linguistic abilities, leaving other abilities out of the assessment process. Given the axiom that you "inspect what you expect" the message that continues to be sent to students is that only certain dimensions of learning are important. Gardner describes some guidelines for "multidimensional assessment" meaning that assessment gathers information about a broad spectrum of abilities and skills (Gardner, 1983). He describes types of assessment on four dimensions (Kulieke, Bakker, et al, 1990). Figure 1 portrays the aspects of multidimensional assessment. The first continuum shows a movement from decontextualized (short answer, fill-in blank, multiple choice, true/false, etc.) to authentic, contextualized tasks such as performances and or products. The second continuum shows movement from a single measure of student learning to multiple measures. The third continuum depicts movement from simple to complex dimensions of learning while the fourth depicts movement from assessment of few dimensions of intelligence to assessment of many dimensions. Multidimensional assessment taps the power and diversity of active learning, creates multiple sources of information to support instructional decision making, and helps students become more reflective and capable learners (Kulieke, Bakker, et al, 1990).

Authenticity

decontextualized contextualized

Number of measures

single multiple

Dimensions of learning

simple complex

Dimensions of intelligence

few many

Figure 1. Multidimensional assessment on four dimensions

Putting this all together, we can extract some very tentative guidelines for the construction of authentic learning and assessment, including (Bastiaens & Martens, 2001): - practicing higher order skills in whole tasks within the context of the lesson;

5 - encouraging understanding of new concepts through exploration by stimulating learners to make their own connections and construct and apply new knowledge in the tasks such that they expand their understanding of how knowledge is constructed; - participating in interactive modes of instruction, sharing ideas and resources; - participating in a collaborative learning environment so as to gain experience in negotiation and using/valuing different points of view;. - working and learning in small heterogeneous (with respect to background, expertise and levels of ability) groups; - using the expert (teacher) as facilitator and coach - resource, guide and supporter; - encouraging and requiring reflection; - embedding seamless and ongoing assessment in the tasks.

As plausible as these guidelines may sound, the are unfortunately so vague that it is hard for instructional designers to actually develop authentic assessment, let alone be sure that students actually perceive them as such. Therefore, our main research questions are: Are current assessment methods are sufficient for assessing competencies and their underlying knowledge, skills, and attitudes. What are the perceptions, opinions/beliefs of students with respect to (authentic) assessment c.q. what are their preferences with respect to types of assessment. How does the authenticity of an assessment method influence student perceptions, opinions/beliefs and preferences? What is the effect of these methods on what is learned and how it is learned? b. Scientific importance of the research, including the importance for the Open University of the Netherlands and the place of the research in the OTEC Research Program The importance of this research for the OUNL lies in the goals, mission and structure of the institution and the need for new assessment methods that are better usable in modern, computer mediated and group based learning environments. First, the OUNL has chosen for competence based learning with assessment as foundation. This is evident in the OTEC research area diagnosis (student and system evaluation) which was operationalized as research aimed at authentic assessment within competence based education and at quality management of competence based curricula. As such, this research fits the needs of both the OUNL and OTEC. Second, the choice made by the OUNL to make increasing use of learning/working in (asynchronous) distributed learning groups has led to a need for new assessment methods which are both individual and collaborative. Portfolio assessment and co-assessment fit these two aspects. c. Design & Methods Phase 1 There are a number of analyses of “state-of-the-art” methods for assessing competence based education (e.g., Vermetten, Daniëls, & Ruijs, 2000; Dochy, Segers, & Sluijsmans, 1999; van der Vleuten & Driessen, 2000). They recommend the use of more authentic assessment and an emphasis on the stimulation and assessment of higher order and metacognitive skills. The first phase involves collecting and ordering the literature followed by determining the greatest common denominator with respect to authentic learning and new assessment techniques. For collection, the AiO will make use of electronic data bases as ERIC, Psychlit and Current Contents. A tentative review of the literature by this proposal’s authors led to the decision to use the following search terms (in combination via Boolean operators): authentic learning, (authentic) assessment, study behavior, learning behavior, opinions/perceptions of students on assessment, preferences for types of assessment. The ordering of the research literature found will be done through a meta-analytic technique known as the ‘lines-of-argument’ synthesis (Noblit & Hare, 1988). This has been shown to be an extremely useful technique for making inferences. These inferences will then be set-off against the competence structure within one of the OUNL knowledge domains.

6 The result is an article elucidating a program of requirements for authentic, competence- based assessment within that domain. This phase will also be used to find and/or develop a number of instruments necessary for phase 2. Examples are: - Assessment Preferences Inventory (e.g., Birenbaum 1997) - Assessment Perception and Attitude Inventory (e.g., Birenbaum & Feldman, 1998) - Study and Learning Behavior Inventory (e.g., Vermunt, 1992)

7 Summary Research Are current assessment methods sufficient for assessing competencies and question their underlying knowledge, skills, and attitudes? Time frame: 12 months Key decisions / OUNL-course as study domain (subject, length, et ecetera)? choices: Parallel course outside of OUNL? Existing instruments? Products: Article on meta-analysis and program of requirements Two instruments for Phases 2 and 3 International presentation National presentation

Phase 2 The AiO will carry out a series of (at least) four parallel experiments with participants studying an OUNL-course with a maximum study length of (preferably) three months. The experiments will be carried out using a time series quasi-experimental design (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Cook & Campbell, 1979). This design has been chosen because it is comparable to traditional pretest-posttest designs, with as extra benefit that multiple / repeated measures are possible both prior to and after an intervention (in our case the disclosure of the type of assessment to the participants). This design also allows for trend information, i.e., changes between a specific pair of observations (i.e., just before and just after an intervention) can be compared with all other pairs of observations. If the intervention caused a change (as opposed to elapsed time, changes in behavior due to maturation, aging, and/or experiences in other courses), then this should be apparent between the two observations when contrasted with all other pairs of observations. All groups receive the same materials and make use of the same authentic learning environment (pedagogy, tools, et cetera). One group will follow the course of study without being formally informed as to the type of assessment that will be used. This group serves as a quasi-control group. A second group will be informed that standard multiple-choice assessment will be carried out at the end of the course of study (Treatment 1). At least two groups will be informed that they will be assessed at the end of the course of study via either portfolio assessment (Treatment 2) or co-assessment (Treatment 3). The study and learning behavior of the students, as well as their attitudes and perceptions about the assessment (and its relation to authentic learning) will be ascertained at certain points during the experiments (Observations 1 through N). The learners in the three treatment conditions will be informed of the mode of assessment at a certain point in the course of study (between two observations at approximately week 3 in the course of study). Nothing further is changed.

start week 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

observation

Entry measure = Measure of entrance study behavior, test attitudes, test preferences, learning style

Observation = Measure of study behavior, test attitudes, test preferences

Treatment = Informing of assessment type (except for quasi-control group)

Exit measure = Measure of exit study behavior, test attitudes, test preferences, learning style (after exam)

All groups will be assessed with respect to three intervening variables (opinions, perceptions, and test preferences). These measurements will be performed with those instruments found / developed in Phase 1. During the study the opinions, perceptions, and test preferences will be determined at all observation moments; study and learning behavior 8 will also be determined at the observation moments (possibly supported by thinking aloud protocols). This will allow us to study the relation between opinions, perceptions, and study behavior and the possible changes evoked by the treatments. Learning will be assessed at the end of the course as a control for learning. (After all, the hypothesis is that knowledge of the authentic assessment during study will positively affect study behavior and thus positively influences learning. It is necessary therefore to determine whether learning was not negatively influenced by the treatment) Finally, decisions will be made on revision the authentic assessment procedures based upon the results of the experiments (the so-called Revised Assessment Tools). Also, a decision will be made as to the development of tools for the acquisition of the skills necessary for effective and efficient use of the assessment types within the study / learning process (the so-called Skill Acquisition Tools).

Summary Research What are the perceptions, opinions/beliefs of students with respect to question (authentic) assessment? What are their preferences with respect to types of (authentic) assessment? How does the authenticity of an assessment method influence student perceptions, opinions/beliefs and preferences? Time frame: 15 months Key decisions / Refining of the authentic learning environments choices: Development of tools for the acquisition of the skills necessary for effective and efficient use of the assessment types within the study / learning process Products: Article on the influence of chosen assessment forms on the perceptions and attitudes of learners towards assessment Article on the influence of perceptions and attitudes towards assessment on learning-/study behavior International presentation European presentation National presentation

Phase 3 The AiO will again carry out four parallel experiments with participants studying an OUNL-course with a maximum study length of (preferably) three months. The experiments will again be carried out using a time series quasi-experimental design (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Cook & Campbell, 1979). Based upon the decisions made in Phase 2 as to the development of the Skill Acquisition Tools, Phase 3 will begin with the development of these tools. These tools are comparable, and possibly – seeing the timing – based upon the tools developed in the earlier named research of Kirschner, Prins, and Sluijsmans (ePAL) for developing peer- and self-assessment skills. The experimental design will be comparable to the design in Phase 2. Two of the groups (the quasi-control groups) will receive the two Revised Assessment Tools and will make use of the refined authentic learning environment (pedagogy, tools, et cetera). The participants in the two experimental treatment conditions will not only receive the Revised Assessment Tools in the refined authentic learning environment, but they will also receive the Skill Acquisition Tools. The study and learning behavior of the students, as well as their attitudes and perceptions towards the assessment (and its relation to authentic learning) will be ascertained as in Phase 2. Finally, learning behavior and learning outcomes (qualitative and quantitative) will be ascertained.

Summary Research What is the effect of different methods of (authentic) assessment on what is question learned and how it is learned? Time frame: 12 months Key decisions / None choices: Products: Article on authentic assessment and learning outcomes International presentation National presentation 9 Phase 4 In this phase (9 months) the AiO will prepare her/his thesis (5 months), have it reviewed (two months), have it printed (1 month) and prepare a defense (1 month). d. Literature Bennett, R. E., & Ward, W.C. (1993). Construction versus choice in cognitive measurement. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347-364. Birenbaum, M. (1996). Assessment 2000: Towards a pluralistic approach to assessment. In M. Birenbaum, & F.J.R.C. Dochy, (Eds.). Alternatives in assessment of achievements, learning processes and prior knowledge (pp. 4-29). Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Boud, D. J. (1990). Assessment and the promotion of academic values, Studies in Higher Education, 15(1), l01-111. Boud, D. J. & Falchikov, N. (1989). Quantitative Studies of Self-assessment in Higher Education: a Critical Analysis of Findings. Higher Education, 18(5), 529-549. Brown, S. & Knight, P. (1994). Assessing learners in higher education. London: Kogan Page. Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design & analysis for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally. Dochy, F., Segers, M., & Sluijsmans, D. (1999). The use of self-, peer and co-assessment in higher education: a review. Studies in Higher Education, 24 (3), 331-350. Frederiksen, N. (1984). The real test bias: Influences of testing on teaching and learning. American Psychologist, 39, 193-202. Gaver, W. (1991). "Technology affordances," Proceedings of CHI 1991 (New Orleans, Louisiana, April 28-May 2, 1991) ACM, New York, pp. 79-84. Gaver, W. (1996). Affordances for interaction: The social is material for design. Ecological Psychology 8(2), 111,129. Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin. Gipps, C. & James, M. (1996) Assessment matched to learning. Paper presented in a symposium of the BERA Assessment Policy Task Group, on Thursday 12 September 1996, at the BERA Conference held at the University of Lancaster. London Institute of Education; Cambridge Institute of Education. Retrieved March 30, 2002 from http://brs.leeds.ac.uk/cgi-bin/brs_engine? Gardner, H., (1983). Frames Of Mind The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: BasicBooks. Glaser, R. M. (1998). Reinventing Assessment and Accountability to Help All Children Learn. Introductory remarks at the 1998 CRESST Conference. Retrieved March 30, 2002 from http://cresst96.cse.ucla.edu/CRESST/pages/glaserconf.htm Heron, J. (1981). Assessment revisited. In D. J. Boud (Ed.) Developing student autonomy in learning, London: Kogan Page. Honebein, P. C. (1996). Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. In B. G. Wilson (Ed.), Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design (pp. 11-24). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. Jonassen (1992) Evaluating Constructivist Learning. In Thomas M. Duffy & David H. Jonassen, (Eds.), Constructivism and the Technology of Instruction: A Conversation. Hillsdale, N.J., London : Erlbaum, 1992 Kirschner, P.A., Carr, C, & van Merriënboer, J. (submitted). How expert designers design. McDowell, L. (1995). The Impact of Innovative Assessment on Student Learning. Innovations in Education and Training International, 32,(4), 302-313. Montgomery, B. (1995). Portfolios as critical anchors for continuous learning. In A.L. Cost & B. Kallick (Eds.), Assessment in the learning organization: Shifting the paradigm, (pp 205- 210). Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

10 Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography : Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage Publication. Prodromou, L. (1995). The backwash effect: from testing to teaching, ELT Journal, 49(1), 13-25 Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to teach in higher education. London: Routledge. Reeves, T. C. & Okey, J. R. (1996). Alternative assessment for constructivist learning environments. In B. G. Wilson (Ed.), Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design (191-202). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. Sambell, K. & Johnson, R. (1998). Assessment and the expanded text: Students' perceptions of the changing English curriculum. Paper presented at Higher Education Close Up, 6-8 July 1998 at University of Central Lancashire, Preston. Retrieved March 30, 2002 from the World Wide Web at http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/000000750.htm Spandel, V. (1997). Reflections on portfolios. In G.D. Phye (Ed.) Handbook of academic learning: Perspectives. theory and models (pp 573-591). San Diego: Academic Press. Topping, K. 1998. The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature. In S. Goodlad (Ed.), Mentoring and tutoring by students (pp. 49-69). London: Kogan Page. Traub, R. E., & MacRury, K. (1990). Multiple-choice vs. free response in the testing of scholastic achievement. In K. Ingenkamp & R.S. Jager (Eds.), Test und tends 8: Jahrbuch der pädagogischen Diagnostik. Weinheim und Base: Beltz Verlag. Vermetten, Y., Daniëls, J., & Ruijs, L. (2000). Inzet van assessment: Waarom, wat, hoe, wanneer en door wie? [Using assessment: Why, what, how, when, and by whom?] (OTEC report 2001/13). Heerlen, The Netherlands: Open Universiteit Nederland, Onderwijstechnologisch Expertisecentrum. Van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (1996). The assessment of professional competence: Development, research, and practical implications. Advances in Health Science Education, 1(1), 41-67. Van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Driessen, E. (2000). Toesting in probleemgestuurd onderwijs [Testing in problem based learning]. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Vermunt, J. (1992). Leerstijlen en sturen van leerprocessen in het hoger onderwijs. Naar procesgerichte instructie in zelfstandig denken [Learning styles and regulating of learning in higher education. Towards process-oriented instruction in autonomous thinking]. Doctoral dissertation. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. Wiggins, G. (1989). Teaching to the (authentic) test. Educational Leadership, 46(7), 41-47. Wolf, D. P. (1989). Portfolio assessment: sampling student work. Educational Leadership, 46(7), 35-39. Zeidner, M. (1987). Essay versus multiple-choice classroom exams: The student’s perspective. Journal of Educational Research, 80, 352-358. Zoller, U., & Ben-Chaim, D. (1990). Interaction between examination-type anxiety state, and academic achievement in college science; An action-oriented research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 26, 65-77.

9 Work program and planning Detailed description of the research for the first 12 months month activity 1 Settling in period for the AiO in the research area - studying basis literature - planning the training and coaching of the AiO 2 - 5 Literature research and schooling of the AiO on conducting meta-studies / ‘lines- of-argument’ synthesis 6 - 7 Building of a systematic overview of the literature based upon the chosen criteria 8 - 12 ‘Lines-of-argument’ synthesis - Article 7 - 12 Set-up of empirical research, i.e., selection of course Choice and/or development of research instruments Formative evaluation of the instruments 12 Construction of design guidelines - Article 13 Evaluation – Go / No Go decision on continuation of the research 11 IV-02 I-03 II-03 III-03 IV-03 I-04 II-04 III-04 IV-04 I-05 II-05 III-05 IV-05 I-06 II-06 III-06

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4

P1 - Acclimatisation P1 - Literature search P1 - Meta-analysis P1 - Set-up P2

P2 - Preparation experiment 1 P2 - Experimentation P2 - Reporting P2 - Revision / set-up P3

P3 - Preparation experiment 2 P3 - Experimentation P3 - Reporting

Thesis

10 External partners There are discussions with the Department of Industrial Design in Eindhoven

11 Motivation for external partners The Department of Industrial Design is a true competence-based environment that does not make use of either lectures or examinations, but rather project centered learning in teams with assessment solely based upon the results of the projects and the presentation thereof. For both the ideas at the basis of this research project as well as the types of assessment that will be carried out, this department appears to be an interesting partner.

12