World Food Prices: Causes and Consequences

Alex F. McCalla

Professor Emeritus, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Davis, 1 Shields Avenue, Davis, California, USA 95616 (phone: 530-752-1529; fax 530-752-5614; e- mail: [email protected])

INTRODUCTION

It is a great honor to be invited to give the CAES Fellow’s Address in my home country, to give it on the 400th Anniversary of the founding of Quebec and to do it in Quebec City. The topic given me is current, topical and emotional. Food prices are always controversial, either too high for consumers or too low for farmers and often unstable. The paper is divided into four parts: the first places the current situation in historical context; the second identifies some competing explanations for high food prices; the third analyzes in more detail the Structural Change/Shock story; and the fourth notes the consequences, especially for Developing Countries. The paper closes with the big question - When the bubble breaks, will long run real prices be on a higher level with a stable or increasing trend or will we back to “Business as Usual” with real prices dropping down to the previous level and continuing their 150 year downward trend?

THE CURRENT SITUATION IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

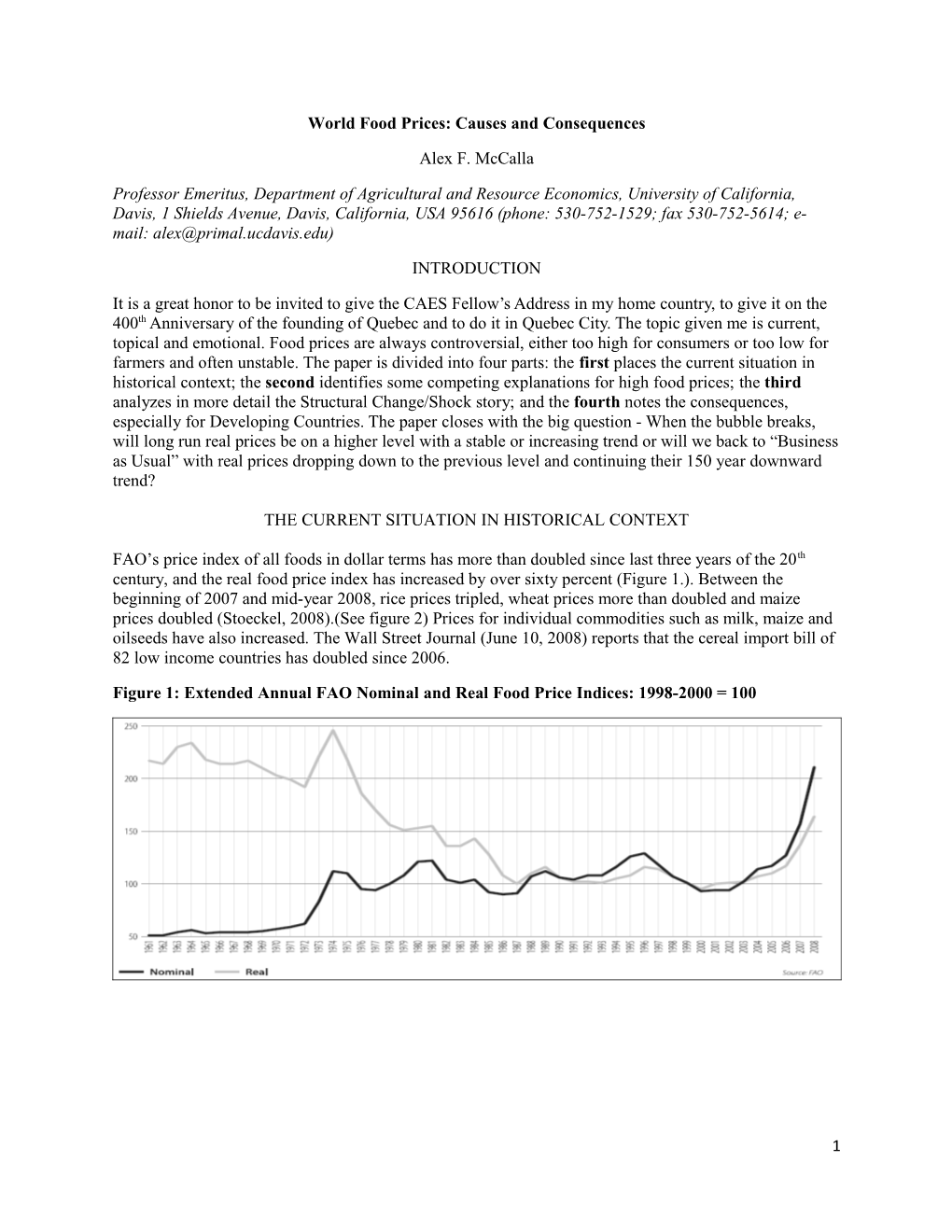

FAO’s price index of all foods in dollar terms has more than doubled since last three years of the 20th century, and the real food price index has increased by over sixty percent (Figure 1.). Between the beginning of 2007 and mid-year 2008, rice prices tripled, wheat prices more than doubled and maize prices doubled (Stoeckel, 2008).(See figure 2) Prices for individual commodities such as milk, maize and oilseeds have also increased. The Wall Street Journal (June 10, 2008) reports that the cereal import bill of 82 low income countries has doubled since 2006.

Figure 1: Extended Annual FAO Nominal and Real Food Price Indices: 1998-2000 = 100

1 Figure 2: Rapidly Rising Prices -2000- 2008

The new situation: Surge in prices Commodity prices (US$/ton)

600 100 Corn Wheat 500 80 400 Rice Oil (right scale) 60 300 40 200

100 20

0 0

J oachim von Braun, IFPRI, April 2008 Source: Data from FAO 2008 and IMF 2008.

Before proceeding with trying to explain the current situation it is worthwhile to review a bit of history. The rapid expansion of grain production in “newly settled areas” – the Americas, Australia, South Africa and South Asia -coupled with the invention of the steam ship greatly expanded world trade in grains in the second half of the 19th Century, particularly after 1870. In the 20th Century increasing yields further expanded production capacity. The result has been that since 1870’s Long Run (LR) real secular grain prices have been declining. What do the dates 1910-14, 1972-74 and 1995-96 have in common? They were the exceptions, earlier price spikes, after which real prices returned to the previous downward trend. Therefore one basic question is- when this spike is over will the LR trend be re-established or will real prices settle at a higher level and even possibly increase? The paper returns to this question at end.

Looking again at Figure 2, notice a similar path for oil prices. Note also that rice prices rose later and faster after some major exporters of rice announced export embargoes. While prices have moderated somewhat from extreme peaks (at one point wheat prices reached over $US 12.00 /bushel for wheat, 3 times last year’s price) But all grains prices as of the end of August 2008 remain more than double prices that prevailed at the beginning of 2007. Further, volatility of prices has increased as is shown by the fact that the difference between high and low prices on near futures contracts for wheat and corn is around 300 percent. There is no evidence that the price run up will soon be over. Floods in Mid West and continued drought in Australia could deliver more weather shocks. Everyone agrees nominal prices will decline from final peak but when and by how much remains unclear. Therefore the Big Questions are -What will be the new real price level? And will the LR trend be up or down? Later in the paper we review some empirical attempts to answer these questions.

2 SOME COMPETING EXPLANATIONS

This price spike has stimulated a large number of writings about the nature of the price increases, their causes, their likely duration and the nature of a return to more normal times. Within the past few months IFPRI, (May 2008), IMF (March 2008), FAO (April 2008), UNCTAD (May 2008),OECD/FAO (2008),USDA/ERS (Trostle May 2008), Australia (Stoeckel, June 2008) and Farm Foundation (Abbott, Hurt and Tyner, July 2008) have all published analysis. The New York Times continued to run a series under the general heading “The Food Chain” from January through August 2008 and The Economist has carried many articles in the last six months. All these analyses do not however agree on the causes, likely duration and ultimate end of the spike. Although all do agree prices will come down from current levels. There are at least four competing hypotheses (stories) floating about which we briefly review here.

Story One: Macroeconomic Factors are Driving Price Rises: This model argues that we are experiencing a broad commodity boom. Oil, minerals (especially gold, silver and copper) and agricultural commodity prices are rising in a similar pattern which suggests that broad macro economic variables are driving the boom. Explanations include the rapid decline in the value of the US dollar. Given that all global commodity markets are denominated in dollars, the declining dollars makes all commodities cheaper to the rest of the world, driving up demand and prices (Hanke &Ransom). The August 2008 appreciation of the US dollar which was accompanied by declining commodity prices seemed to support this notion. In parallel US concerns about recession led to successive cuts in nominal and real interest rates which reduced the price of storage and encouraged buying and holding real commodities. This phenomenon drives up all real commodity prices (Frankel 2008). The IMF argues these are supporting but not primary factors (IMF, p. 6)

Story Two: Speculators are Driving Prices Up and Increasing Volatility: In periods of uncertainty/recession, investors shift out of monetary assets into real assets including commodities. Further the rise in the magnitude of hedge, and particularly index, funds seems to have led to large increases in non-traditional investments in commodity markets. These fund investors are currently very long (betting on continued price increases) in Commodity markets. . The IMF discusses this and concludes that speculation alone is unlikely to drive sustained price increases (IMF, pp 6-8).

Story Three: Simultaneous and Big Shocks are driving Prices up. International commodity markets operate on a knife’s edge between the rate of supply growth and demand growth. Several years of weather impacts including Europe in 2006, North America in 2006/2007 and a continuing severe drought in Australia 2006-2008 have drawn stocks down to critical lows. This coupled with the surge in bio fuel demand has created a price spike. The spike will surely end if supply in 2008 shifts when conditions return to normal (See Figure 3). FAO suggest these are contributing factors.

3 Figure 3: Commodity Prices on the Knife’s Edge

Small quantity changes have large effects on cereal prices 2000=100P S D 2007 204 2006

D2000 153

100

D2007 S2006

S2000

1,917 2,120 Q 2,070 million tons J oachim von Braun, IFPRI, April 2008 Source: Based on data from FAO 2003, 2005-08.

Story Four: Combination of Permanent Structural Changes in Supply and Demand Conditions, Exacerbated by Shocks. This is the predominant story in the literature. This story argues that there is a confluence of permanent and transitory factors that are driving the current price situation. An amazing number of analysts identify a similar set of causes, differing only on the relative size of impacts. IFPRI, WB, IMF, USDA/ERS, FAO, OECD, Govt. of Australia, Farm Foundation, WSJ, NY Times, ad infinitum all see structural change in Supply & Demand which are pushing agricultural commodity prices up. When perturbed by shocks or rapid shifts in parameters, price increases are magnified. The implication appears to be that real prices after the blip should be permanently higher.

On the demand side, rapid growth and rising incomes in emerging economies such as India and China has increased that rate of demand expansion. Urbanization and global growth means demands for a larger and more varied food supply. Finally at least some of the increase in bio fuel demand will be around for a while. On the supply side, the rate of increase supply has slowed over the past decade because of declining rates of productivity growth (See figure 4), and increased competition for water and land. Investments in agricultural R&D have declined globally as has investment in agricultural development.

4 Figure 4: Declining Productivity Growth

Productivity growth is declining ) % ( 6 e t

a maize r

h 5

t rice w

o wheat r 4 g

l a u

n 3 n a

e 2 g a r e

v 1 A

0 1963 1967 1971 1975 1979 1983 1987 1991 1995 1999 2003

J oachim von Braun, IFPRI, April 2008 Source: World Development Report 2008.

Finally higher petroleum prices have permanently increased the costs of agricultural production (See Figure 5).

Figure 5: Higher Input Costs Higher input costs: Global fertilizer prices tripled in 2007

800 World Fertilizer Prices, 2000-2008, US$/mt 700

600 DAP, US Gulf 500

400

300

200

100 MOP, Vancouver Urea, Arab Gulf, prilled

0 Jan-00 Jan-01 Jan-02 Jan-03 Jan-04 Jan-05 Jan-06 Jan-07 Jan-08

J oachim von Braun, IFPRI, April 2008 Source: IFDC 2008.

5 Global grain consumption has exceeded global production in 7 of the last 8 years (Figure 6). The result has been a drawdown of stocks to the lowest levels since the early 1970’s (Figure7). Thus when shocks like weather and the surge in bio fuel demand occur, they have caused prices to rise sharply.

Figure 6: Consumption Outstrips Supply

World cereal production: Not growing enough

Million tons Total Million tons

1,200 2,000

900 1,600

600

1,200 300

0 800 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007* Wheat Coarse grains Rice Total (right) Source: Data from FAO 2003, 2005-08. J oachim von Braun, IFPRI, April 2008 * Forecast.

Figure 7: Declining Global Stocks

6 The real explanation probably has elements of all four stories. However if one believes any or all of the first three, the long run outcome is clear- when the contributing factors revert to “ normal”- the bubble will break and we will resume the same long run downward path in real prices as happened after earlier episodes.

Only story four includes the possibility of a different ending. Two outcomes seem possible. After the spike, nominal prices fall but stabilize at higher levels of real prices and continue their secular decline, likely at a slower rate. A second variant would be that the permanent structural changes are sufficiently strong that the historical pattern of declining real prices is over and real prices will rise modestly over the foreseeable future. In the following paragraphs three empirical estimations are reviewed which provide some support for one or the other of these possibilities.

THE STRUCTURAL/SHOCK STORY-SOME EMPIRICAL ESTIMATES

The first is a set of projections to 2017 jointly prepared by OECD and FAO in early 2008. Figure 8 shows the OECD-FAO price projections. The figure compares the average level of prices for the past decade (which were already higher than prices in the 1990s) with average expected nominal and real prices for the coming decade. Nominal prices of all major food groups are likely to increase, and this is also so for most, but not all, real prices (in real US dollars). For beef and pig meat, real prices are expected to decline slightly or stay constant. For sugar and rice they are expected to increase by between five and 10 percent, reflecting in the case of rice the expected slow growth of demand in Asia, and for sugar a high supply response capacity. By far the highest real price increase is expected in vegetable oils, more than 50 percent, while for the other commodities the real price increases range between 25 and 30 percent. Compared to the prices in the early part of 2008, this means that a number of the high prices are expected to drop back significantly over the next one or two years, but will remain much higher than in the last decade.

Figure 8: Expected World Commodity Prices for the Coming Decade

These projected world wheat, rice, and oilseeds prices are however likely very sensitive to key assumptions in the OECD-FAO model. They therefore run five scenarios to explore the sensitivity of

7 their 2017 projections to the baseline assumptions. These five different scenarios are (OECD-FAO, 2008):

1. Instead of rising rapidly over the next decade, bio-fuels production would be maintained at the level of 2007. For the two main bio-fuels inputs, vegetable oils and coarse grains, this would lead to a reduction of 2017 prices by 15 and 12 percent respectively, more than for the impact of any other scenario change. Wheat prices would be affected indirectly with a reduction of around six percent. Simulations by Rosegrant, using the IFPRI- IMPACT model reported on below, come to similar conclusions. Clearly these results suggest that there should no longer any question that bio-fuel policy, and the resulting increase in feed stock production, will have a major impact on future food prices.

2. Keeping oil prices constant at 72 dollars per barrel, the average 2007 price, would reduce maize and oilseed prices by around 10 % and wheat prices by 7 % compared to their baseline projected 2017 prices. This shows the very high sensitivity of food production costs and prices to energy prices.

3. If the rate of growth in EE5 countries (China, India, Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa) were reduced by half relative to current high projections, this would lead to price reductions in vegetable oils, that are highly income elastic, of about 10 percent, while it would reduce maize by significantly less and leave the wheat price almost unchanged.

4. If the US dollar were to appreciate by 10 percent relative to the baseline scenario (which already incorporates a modest expected US dollar appreciation), it would increase incentives in exporting countries to produce more, and reduce import demand elsewhere. The combined effect would reduce all three prices by about 5 percent relative to their baseline.

5. If crop yields at the end of the period would rise by an additional 5 %, it would reduce wheat and maize prices by 6 to 8 percent, but leave vegetable oil prices relatively unaffected.

These outcomes are shown in Figure 9.

8 Figure 9: Sensitivity of Projected World Prices to Changes in Five Key Assumptions, Percentage Difference from Baseline Values, 2017

The second study is a recent World Bank report prepared for the G8 Hokkaido-Tokyo Summit which reaches similar conclusions which are quoted here verbatim:

“High food prices are likely to persist in the medium term. While forecasts in the current environment are subject to considerable uncertainty, we expect food prices will remain high in 2008 and 2009, before they begin to decline. Prices are likely to remain well above 2004 levels through 2015 for most food crops (Table 1). These forecasts are broadly consistent with those of other agencies such as USDA and OECD-FAO. While world grain production is forecast to grow, increased utilization is expected to lead to a decline in stocks in the 2007/2008 crop year. FAO predicts that total grain end-stocks will reach a 25-year low by the end of 2008.” (World Bank, p. 3)

Table 1. Index of projected real food crop prices : 2004 = 100 Real Prices 2007 2008 2009 2010 2015 Maize 139 175 165 155 148 Wheat 154 215 191 166 140 Rice 130 243 208 183 160 Soybeans 119 156 147 139 115 Soybean oil 136 187 173 160 110 Sugar 133 157 167 176 182 Source: World Bank, DEC Prospects Group

9 The third empirical study is a recent IFPRI analysis using their IMPACT Model which makes projections to 2015. It projects that real grain and oilseed prices will not decline from levels they reached in late 2007 and will show a modest increase through 2015. Figure 10 shows these projections for rice, wheat, maize, oil seeds and soybeans. This is one of the first substantive analyses that seem to support the proposition that the long term secular decline in grain and oilseed prices may be over. IFPRI continues to maintain a watching brief on food prices. IFPRI’s Director-General participated in a debate in the July 29-August 8, 2008 edition of the Economist arguing the negative of the Proposition “This house believes there is an upside for humanity in the rise in food prices”, arguing that the negative impact on poor consumers in developing countries far exceeds benefits to farmers both small and large.

Figure 10 : Long Term Crop Price Projections to IFPRI’s scenarios [Models for changes in structural supply and demand factors (2000-05 and 2006-15)]

US$/ton 300

200

100

0 2000 2005 2010 2015

Rice Wheat Maize Oilseeds Soybean

Source: M. Rosegrant (prelim. results with IMPACT-WATER). Joachim von Braun, IFPRI, April 2008

Predicting prices is hazardous at any time but is especially perilous for making long term predictions. The situation now is particularly difficult because of uncertainties on both the demand and supply sides of the market. The traditional drivers of food demand are population, income growth and urbanization. The latter two change demand patterns away from cereals, towards meat, dairy, fruits and vegetables. Population growth remains much higher in the developing world than the developed world where it is falling fast to zero. It remains at around slightly less than 2 percent in Africa and at 2 percent for all Least Developed Countries (LDC). Clearly the main impetus of population growth on demand will come from developing countries. The big uncertainties on the demand side are future policies with respect to bio- fuels and technological developments regarding new methods of bio-fuel production, as for example cellulosic ethanol.

There are many uncertain factors on the supply side: little progress in reducing agricultural trade barriers and subsidies in rich countries; slowing yield growth; constraints on the use of bio-technology; little investment in irrigation; deterioration of existing irrigated areas; environmental constraints; loss of land to

10 competing uses- urbanization, infrastructure environmental set asides-; and water constraints. The combination of these adds to the uncertainty.

These three projections, while admittedly highly dependent on underlying assumptions, are the only attempts so far to quantify likely future outcomes. The OECD/FAO conclusion is worth quoting because it seems to come closest to a consensus view.

“World reference prices in nominal terms for almost all agricultural commodities covered in this report are at or above previous record levels. This will not last and prices will gradually come down because of the transitory nature of some of the factors that are behind the recent hikes. But there is strong reason to believe that there are now also permanent factors underpinning prices that will work to keep them both at higher average levels than in the past and reduce the long-term decline in real terms”(OECD/FAO p.11)

CONSEQUENCES, ESPECIALLY FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

The short term consequences of the price rises are both positive and negative. Farmers, particularly large ones in countries where world prices are transmitted to farmers, should be better off despite the fact that rising petroleum prices have also significantly increased production and marketing costs. An Economic Research Service, USDA Briefing Room headline reads: “2008 Net Farm Income Is Forecast To Be At Record Level” (ERS, USDA, 2008). The consequences for small farmers in developing countries will depend on whether they net food surplus producers, and on whether world prices are transmitted to them. Consequences for poor urban consumers in developing countries are unequivocally negative in the short run. In the longer run improved farm incomes tend to push up rural and urban wages which to some extent could mitigate longer term price impacts.

At the national level the consequences now for poor net importing developing countries are severe. Rising foreign exchange costs for food imports hit hard, particularly if the country is not an oil or mineral exporter. Countries that maintain low domestic food prices as a safety net have experienced rising fiscal costs of domestic feeding programs- for Tunisia the estimated increase in costs is from $200 Million to $1 Billion. Many food deficit countries are pushing back towards inefficient self-sufficiency because they don’t trust world markets. The World Bank estimates that up to 100 million people could fall back into poverty in the next 6 months (Ivanic and Martin, 2008). IFPRI lists over 25 countries where food price related protests have occurred since the beginning of 2007. For the poorest of the poor concentrated in South Asia and Sub Saharan Africa the consequences are devastating.

Another way of looking at the issue is to see what the consequences of higher food prices are for a country’s balance of trade. This is summarized in Figure 11. Highly specialized net exporters of food such as Argentina and Kazakhstan will see their trade balance improve by more than 1 percent, while other food exporters such as Brazil, the US, Russia and Australia will experience trade balances improvements of zero to one percent. Net food importers include much of the developing World, with the exception of Thailand, Indonesia, and about half the South American countries. The African Continent will be hurt, with the hardest hit countries including all of North Africa and much of Eastern Africa, who will see their net trade balance deteriorate by more than one percent. Net exporters of energy and other raw materials will experience rising prices to counterbalance food price increases. In Algeria and Libya the higher costs of food imports could be more than offset by higher oil prices, while Eastern African countries will see a double hit from higher oil and food prices. .

11 Figure 11: Impact of Food Price Increases on Trade Balances

Apart from exchange rate movements, policy factors determine how much of the international price rises are transferred to the domestic economy. In the short run policy can slow down this transmission considerably. Developing countries have acted quickly to reduce the impact of international prices on their consumers: Almost half of 77 countries surveyed by FAO in early 2008 had reduced import taxes on food (Figure 12). Such reductions may worsen fiscal imbalances that may arise from higher food bills. For these countries the price reduction achievable is sharply limited, and cannot exceed the tax collected prior to their reduction. Therefore even more countries (55%) have resorted to food subsidies or price controls. Again these measures may or may not be fiscally sustainable. More sustainable is dipping into domestic food reserves, which may have been accumulated precisely for episodes of scarcity arising from international price increases or domestic production shortfalls. Only about 25% of countries have been able to do so, however. An even lower percentage of countries, only about 17 percent, have yet responded via measures to increase the food supply.

12 Figure 12: Policy actions to address high food prices

Source: FAO 2008

As a consequence of these policy measures the pass-through of higher rice prices to domestic prices ranged from 6, 9 and 11 percent of the international price rise respectively in the Philippines, India and Vietnam, all of them net food exporters. The price rises were 43, 53, and 64 percent respectively in Bangladesh, Indonesia and China who import some and export other foods. Argentina, a major wheat exporter has been able to keep the price rise of wheat to less than a third the price rise in the international price, while in Chile domestic prices almost fully reflect the rises in the international price.

The longer term consequences will depend on policy responses not yet fully undertaken. Long term food security will depend on continued expansion of supply in line with demand growth. This will require expanded investments in agricultural R & D, finding ways to improve water use efficiency, adapting to global warming, removing the scourge of agricultural protectionism which has led again to a WTO collapse, and pursuing sensible policies. The historical story was that Malthus was kept at bay by expanded area in the 19th Century and rising productivity in the 20th Century and real prices fell over 75% since 1870. Is that trend broken? Real prices stopped declining in the 1990’s. What will be the story line for the 21st Century?

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

People as we have seen are debating two questions-First where will prices stabilize-at a higher level or will they return to previous levels and second once having stabilized will they then continue their secular decline or are we in for rising real food prices? Who knows what will happen in a rapidly changing world. I certainly don’t have a crystal ball. What seems clear is that we are in for continued high prices, some argue for 2 years, some much longer. It also seems clear that 30 years of complacency about agricultural research and development has extracted a high cost in terms of productivity and production growth. But

13 will that change if prices fall back down soon to previous levels. Some of us are old enough to remember how quickly we were back in the old mould after the price spikes of the early 1970’s. If the folks telling the first three stories are right, when the bubble breaks, it will be back to normalcy until the next confluence of shocks knocks us off trend again. But no matter what happens there will be adjustment costs. Just look at what has happened to land prices increase in the last two years. What seems for sure is that agricultural and food price instability, uncertainty and dynamic change will be with us for a while. That means lots of need for policy analysis which of course is likely to be good for the next generation of Agricultural Economists.

REFERENCES

Abbott, P.C., C Hurt and W. E. Tyner. 2008. What’s Driving Farm Prices? Oak Brook, IL: Farm Foundation Issue Report, July.

Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture (ERS/USDA). 2008. Washington, D.C.: ERS/USDA, Briefing Room. February 12.

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2008. Soaring Food Prices: Facts, Perspectives, Impacts And Actions Required. High-Level Conference on World Food Security: The Challenges of Climate Change and Bio energy, Rome, 3 - 5 June

Frankel, J. 2008. An Explanation of Soaring Commodity Prices. VoxEU.org : 25 March.

Hanke, S. H. and D. Ransom, 2008. The Fed and the Price of Rice. Wall Street Journal, June 10.

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). 2008. High Food Prices: The What, Who, and How of Proposed Policy Actions. Washington D.C. :Policy Brief, May.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2008. Riding a Wave: Soaring Commodity Prices May Have a Lasting Impact. Washington, D.C.: Finance and Development, Volume 45, Number 1 March.

Ivanic, M. and W. Martin. 2008. Implications of Higher Global Food Prices for Poverty in Low-Income Countries. Washington D.C.: World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 4594,

Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN (FAO). 2008. Agricultural Outlook: 2008-2017. Paris and Rome.,

Stoeckel, A. 2008. High Food Prices: Causes, Implications and Solutions. Australian Government, Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. (RIRDC) Publication No 08/100, June

Trostle, R. 2008. Global Agricultural Supply and Demand: Factors Contributing to the Recent Increase in Food Commodity Prices. Washington, D.C.: ERS/USDA WRS-0801, May

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2008. Assessing the Global Food Crisis: Key trade, investment and commodity policies in ensuring sustainable food security and alleviating poverty. Geneva: UNCTAD/OSG/2008/1, May

World Bank, 2008. Double Jeopardy: Responding to High Food and Fuel Prices. G8 Hokkaido-Toyako Summit, July 2, 2008

AFM 08/29/08

14